Shihab dynasty

| Shihab (Chehab) dynasty الشهابيون | |

|---|---|

| Emirs of Mount Lebanon | |

Flag of the Shihab dynasty | |

| Country | Mount Lebanon Emirate, Ottoman Empire |

| Founded | 1697 |

| Founder | Bashir I Haydar I |

| Final ruler | Bashir III |

| Deposition | 1842 |

| Historical Arab states and dynasties |

|---|

|

The Shihab dynasty (alternatively spelled Chehab; Template:Lang-ar, ALA-LC: al-Shihābiyūn) is an Arab family whose members served as the paramount tax farmers and local chiefs of Mount Lebanon from the early 18th to mid-19th century, during Ottoman rule. Their reign began in 1697 after the death of the last Ma'nid chief. The family centralized control over Mount Lebanon, destroying the feudal power of the mostly Druze lords and cultivating the Maronite clergy as an alternative power base of the emirate. The Shihab family allied with Muhammad Ali of Egypt during his occupation of Syria, but was deposed in 1840 when the Egyptians were driven out by an Ottoman-European alliance, leading soon after to the dissolution of the Shihab emirate. Despite losing territorial control, the family remains influential in modern Lebanon, with some members having reached high political office.

History

Origins

The Banu Shihab were purportedly an Arab tribe originally from the Hejaz.[1] According to the 19th-century historian Mikhail Mishaqa, they were descendants of the Banu Makhzum clan of the Quraysh tribe to which the leader of the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Syria, Khalid ibn al-Walid, belonged. Mishaqa held the family's ancestor was a commander in the conquest, Harith, who fell in battle at the Bab Sharqi gate of Damascus during the Muslim siege of that city in 634.[2] At some later point, the tribe settled in the Hauran region south of Damascus.[1][3] In 1172, the Banu Shihab migrated from their home village of Shahba in Jabal Hauran westward to Wadi al-Taym, a plain at the foot of Mount Hermon (Jabal al-Sheikh).[3][4]

Governors of Wadi al-Taym

The 19th-century family histories of the Shihabs by Haydar al-Shihabi and his associate Tannus al-Shidyaq claim that the clan's leader during its migration to Wadi al-Taym was Munqidh ibn Amr (d. 1193), who defeated the Crusaders in an engagement there the following year. The same sources note that he was appointed governor of Wadi al-Taym in 1174 by the Zengid ruler of Damascus, Nur al-Din. Munqidh was succeeded by his son Najm (d. 1224), who was in turn succeeded by his son Amir (d. 1260). The latter allied with the Ma'n family, a Druze clan based in the Chouf region of Mount Lebanon, and defeated the Crusaders in an engagement in 1244.[5] Amir's son and successor, Qurqumaz, took refuge with the Ma'ns in the Chouf during a Mongol invasion in 1280. After his death in 1284, his son Sa'd succeeded him as governor of Wadi al-Taym.[6] The Shihabs continued to govern Wadi al-Taym throughout Mamluk rule (1260–1516), according to the family histories.[7] Their chief, Ali ibn Ahmad, was mentioned by the local Druze chronicler Ibn Sibat (d. 1520) as the governor of Wadi al-Taym in 1478. Ali's son Yunus was mentioned by the contemporary Damascene chroniclers al-Busrawi and Ibn al-Himsi as being involved in a rebellion in Damascus in the late 1490s.[8]

The Ottoman Empire conquered the Mamluk Levant in 1516 and an Ottoman government record from August 1574 directs the governor of Damascus to confiscate the rifle stockpiles of Qasim Shihab,[9] identified by the Shihab family histories as Qasim ibn Mulhim ibn Mansur, a great-grandson of the above-mentioned Yunus ibn Ali.[10] Qasim's son Ahmad was the multazim (limited-term tax farmer) of Wadi al-Taym and neighboring Arqoub in 1592–1600, 1602, 1606, 1610–1615, 1618–1621 and 1628–1630.[11] Ahmad fought alongside the Ma'nid emir Fakhr al-Din II and the Kurdish rebel Ali Janbulad in a revolt against the Ottomans in the Levant in 1606, which was stamped out the following year.[12] When the forces of the Ottoman governor of Damascus Hafiz Ahmed Pasha moved against Ahmad in Wadi al-Taym in 1612, Fakhr al-Din's forces repulsed them.[13] When, in the following year, Hafiz Ahmed Pasha launched an imperial-backed campaign against Fakhr al-Din, Ahmad, his brother Ali and many other local allies of the Ma'ns joined the Ottoman forces.[14] He held the fort of Hasbaya and later that year attacked his brother Ali in the latter's fort of Rashaya.[10] Fakhr al-Din escaped to Europe and returned to Mount Lebanon in 1618, after which Ahmad sent his son Sulayman to welcome his return.[15] By then the Ma'ns had been restored to their tax farms and the governorships of Sidon-Beirut and Safad. Fakhr al-Din reconciled Ahmad and Ali in 1619. Ahmad and his men fought in Fakhr al-Din's army against the governor of Damascus Mustafa Pasha in the decisive Battle of Anjar in 1623,[15] which sealed Fakhr al-Din's growing power in Mount Lebanon. In 1629, Husayn Shihab of Rashaya married the daughter of Emir Mulhim Ma'n.[16][17] In 1650, the Ma'n and Shihab clans defeated a mercenary army of the Druze emir Ali Alam al-Din (Ali's troops were loaned to him by the Ottoman governor of Damascus, who was opposed to Fakhr al-Din).[16]

In 1660, the Ottomans, created the Sidon Eyalet, which included Mount Lebanon and Wadi al-Taym, and under the command of Grand Vizier Koprulu Mehmed Pasha, launched an expedition targeting the Shihabs of Wadi al-Taym and the Shia Muslim Hamade clan of Keserwan.[16] As Ottoman troops raided Wadi al-Taym, the Shihabs fled to the Keserwan region in northern Mount Lebanon seeking Hamade protection.[18] Koprulu Mehmed Pasha issued orders to Emir Ahmad Ma'n to hand over the Shihab emirs, but Emir Ahmad rejected the demand and instead fled to the Keserwan, losing his tax farms in Mount Lebanon in the process.[19] The peasantry of the abandoned regions suffered at the hands of Ottoman troops pursuing the Shihab and Ma'n leaders.[19] The Shihabs fled further north into Syria, taking up shelter at Jabal A'la south of Aleppo until 1663.[19] Four years later, the Ma'ns and their Qaysi coalition defeated the Yamani coalition led by the Alam al-Din family outside the port town of Beirut.[19] Consequently, Emir Ahmad Ma'n regained control of the Mount Lebanon tax farms.[19] The Shihabs further solidified their alliance with the Ma'ns when, in 1674, Musa Shihab married the daughter of Emir Ahmad Ma'n.[16] In 1680, Emir Ahmad mediated a conflict between the Shihabs and the Shia Muslim Harfush clan of the Beqaa Valley, after the latter killed Faris Shihab in 1680 (Faris had recently displaced the Harfush from Baalbek), prompting an armed mobilization by the Shihabs.[20]

In 1693, the Ottoman authorities launched a major military expedition, consisting of 18,500 troops, against Emir Ahmad when he declined a request to suppress the Hamade sheikhs after they raided Byblos, killing forty Ottoman soldiers, including the garrison commander, Ahmad Qalawun, a descendant of Mamluk sultan Qalawun.[21] Emir Ahmad fled and had his tax farms confiscated and transferred to Musa Alam al-Din, who also commandeered the Ma'n palace in Deir al-Qamar.[21] The following year, Emir Ahmad and his Shihab allies mobilized their forces in Wadi al-Taym and conquered the Chouf, forcing Musa Alam al-Din to flee to Sidon. Emir Ahmad was restored his tax farms in 1695.[21]

Regency of Bashir I

When Emir Ahmad Ma'n died without a male heir in 1697, the sheikhs of the Qaysi Druze faction of Mount Lebanon, including the Jumblatt clan, convened in Semqaniyeh and chose Bashir Shihab I to succeed Ahmad as emir of Mountain Lebanon.[3][21] Bashir was related to the Ma'ns through his mother,[3][17] who was the sister of Ahmad Ma'n and the wife of Bashir's father, Husayn Shihab.[17] Due to the influence of Husayn Ma'n, the youngest of Fakhr ad-Din's sons, who was a high-ranking official in the Ottoman imperial government, the Ottoman authorities declined to confirm Bashir's authority over the tax farms of Mount Lebanon; Husayn Ma'n forsake his hereditary claim to the Ma'n emirate in favor of his career as the Ottoman ambassador to India.[22] Instead, the Ottoman authorities appointed Husayn Ma'n's choice, Haydar Shihab, the son of Musa Shihab and Ahmad Ma'n's daughter.[23] Haydar's appointment was confirmed by the governor of Sidon,[24] and agreed upon by the Druze sheikhs, but because Haydar was still a minor, Bashir was kept on as regent.[22]

The transfer of the Ma'n emirate to the Shihabs made the family's chief the holder of a large tax farm that included the Chouf, Gharb, Matn and Keserwan areas of Mount Lebanon.[25] However, the tax farm was not owned by the Shihabi emir and was subject to annual renewal by the Ottoman authorities, who made the ultimate decision to confirm the existing holder or assign the tax farm to another holder, often another Shihab emir or a member of the rival Alam al-Din clan.[24] The Qaysi Druze were motivated to appoint the Shihabs because the Wadi al-Taym-based Shihabs were not involved in the intertribal machinations of the Chouf, their military strength, and their marital ties to the Ma'ns.[21] Other clans, including the Druze Jumblatts and the Maronite Khazens were subsidiary tax farmers, known as muqata'jis, who paid the Ottoman government via the Shihabs. A branch of the Shihab family continued to control Wadi al-Taym, while the Shihabs in Mount Lebanon made Deir al-Qamar their headquarters. The Shihab emir was also formally at the military service of the Ottoman authorities and was required to mobilize forces upon request. The Shihabs' new status made them the preeminent social, fiscal, military, judicial and political power in Mount Lebanon.[25]

In 1698, Bashir gave protection to the Hamade sheikhs when they were sought out by the authorities and successfully mediated between the two sides. He also captured the rebel Mushrif ibn Ali al-Saghir, sheikh of the Shia Muslim Wa'il clan of Bilad Bishara in Jabal Amil (modern South Lebanon), and delivered him and his partisans to the governor of Sidon, who requested Bashir's assistance in the matter. As a result, Bashir was officially endowed with responsibility for the "safekeeping of Sidon Province" between the region of Safad to Keserwan. At the turn of the 18th century, the new governor of Sidon, Arslan Mataraci Pasha, continued the good relationship with Bashir, who by then had appointed a fellow Sunni Muslim Qaysi, Umar al-Zaydani, as the subsidiary tax farmer of Safad. He also secured the allegiance of the Shia Muslim Munkir and Sa'b clans to the Qaysi faction. Bashir was poisoned and died in 1705. The 17th-century Maronite Patriarch and historian, Istifan al-Duwayhi, asserts Haydar, who had since reached adulthood, was responsible for Bashir's death.[24]

Reign of Haydar

Emir Haydar's coming to power brought about an immediate effort on the part of Sidon's governor, Bashir Pasha, a relative of Arlsan Mehmed Pasha, to roll back Shihab authority in the province.[24] To that end, the governor directly appointed Zahir al-Umar, Umar al-Zaydani's son, as the tax farmer of Safad, and directly appointed members of the Wa'il, Munkir and Sa'ab clans as tax farmers of Jabal Amil's subdistricts.[24] The latter two clans thereafter joined the Wa'il's and their pro-Yamani faction.[24] The situation worsened for Emir Haydar when he was ousted by the order of Bashir Pasha and replaced with his Choufi Druze enforcer-turned enemy, Mahmoud Abi Harmoush in 1709.[26] Emir Haydar and his Qaysi allies then fled to the Keserwani village of Ghazir, where they were given protection by the Maronite Hubaysh clan, while Mount Lebanon was overrun by a Yamani coalition led by the Alam al-Din clan.[27] Emir Haydar fled further north to Hermel when Abi Harmoush's forces pursued him to Ghazir, which was plundered.[27]

In 1711, the Qaysi Druze clans mobilized to restore their predominance in Mount Lebanon, and invited Emir Haydar to return and lead their forces.[27] Emir Haydar and the Abu'l Lama family mobilized at Ras al-Matn and were joined by the Jumblatt, Talhuq, Imad, Nakad and Abd al-Malik clans, while the Yamani faction led by Abi Harmoush mobilized at Ain Dara.[27] The Yaman received backing from the governors of Damascus and Sidon, but before the governors' forces joined the Yaman to launch a pincer attack against the Qaysi camp at Ras al-Matn, Emir Haydar launched a preemptive assault against Ain Dara.[27] In the ensuing Battle of Ain Dara, the Yamani forces were routed, the Alam al-Din sheikhs were slain, Abi Harmoush was captured and the Ottoman governors withdrew their forces from Mount Lebanon.[27] Emir Haydar's victory consolidated Shihab political power and the Yamani Druze were eliminated as a rival force; they were forced to leave Mount Lebanon for the Hauran.[28]

Emir Haydar confirmed his Qaysi allies as the tax farmers of Mount Lebanon's tax districts. His victory in Ain Dara also contributed to the rise of the Maronite population in the area, as the newcomers from Tripoli's hinterland replaced the Yamani Druze and Druze numbers decreased due to the Yamani exodus. Thus, an increasing number of Maronite peasants became tenants of the mostly Druze landlords of Mount Lebanon.[28] The Shihabs became the paramount force in Mount Lebanon's social and political configuration as they were the supreme landlords of the area and the principal intermediaries between the local sheikhs and the Ottoman authorities.[28] This arrangement was embraced by the Ottoman governors of Sidon, Tripoli and Damascus. In addition to Mount Lebanon, the Shihabs exercised influence and maintained alliances with the various local powers of the mountain's environs, such as with the Shia Muslim clans of Jabal Amil and the Beqaa Valley, the Maronite-dominated countryside of Tripoli, and the Ottoman administrators of the port cities of Sidon, Beirut and Tripoli.[28]

Reign of Mulhim

Emir Haydar died in 1732 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Mulhim.[29] One of Emir Mulhim's early actions was a punitive expedition against the Wa'il clan of Jabal Amil. The Wa'il kinsmen had painted their horses' tails green in celebration of Emir Haydar's death (Emir Haydar's relations with the Wa'il clan had been poor) and Emir Mulhim took it as a grave insult.[30] In the ensuing campaign, the Wa'ili sheikh, Nasif al-Nassar, was captured, albeit briefly. Emir Mulhim had the support of Sidon's governor in his actions in Jabal Amil.[30]

Beginning in the 1740s, a new factionalism developed among the Druze clans.[31] One faction was led by the Jumblatt clan and was known as the Jumblatti faction, while the Imad, Talhuq and Abd al-Malik clans formed the Imad-led Yazbak faction.[31] Thus Qaysi-Yamani politics had been replaced with the Jumblatti-Yazbaki rivalry.[32] In 1748, Emir Mulhim, under the orders of the governor of Damascus, burned properties belonging to the Talhuq and Abd al-Malik clans as punishment for the Yazbaki harboring of a fugitive from Damascus Eyalet. Afterward, Emir Mulhim compensated the Talhuqs.[31] In 1749, he succeeded in adding the tax farm of Beirut to his domain, after persuading Sidon's governor to transfer the tax farm. He accomplished this by having the Talhuq clan raid the city and demonstrate the ineffectiveness of its deputy governor.[31]

Power struggle for the emirate

Emir Mulhim became ill and was forced to resign in 1753 by his brothers, emirs Mansur and Ahmad, who were backed by the Druze sheikhs.[31] Emir Mulhim retired in Beirut, but he and his son Qasim attempted to wrest back control of the emirate using his relationship with an imperial official.[31] They were unsuccessful and Emir Mulhim died in 1759.[31] The following year, Emir Qasim was appointed in place of Emir Mansur by the governor of Sidon.[31] However, soon after, emirs Mansur and Ahmad bribed the governor and regained the Shihabi tax farm.[31] Relations between the brothers soured as each sought paramountcy. Emir Ahmad rallied the support of the Yazbaki Druze,[31] and was able to briefly oust Emir Mansur from the Shihabi headquarters in Deir al-Qamar.[32] Emir Mansur, meanwhile, relied on the Jumblatti faction and the governor of Sidon, who mobilized his troops in Beirut in support of Emir Mansur.[31] With this support, Emir Mansur retook Deir al-Qamar and Emir Ahmad fled.[32] Sheikh Ali Jumblatt and Sheikh Yazbak Imad managed to reconcile emirs Ahmad and Mansur, with the former relinquishing his claim on the emirate and was permitted to reside in Deir al-Qamar.[32]

Another son of Emir Mulhim, Emir Yusuf, had backed Emir Ahmad in his struggle and had his properties in Chouf confiscated by Emir Mansur.[31] Emir Yusuf, who was raised as a Maronite Catholic but publicly presented himself as a Sunni Muslim, gained protection from Sheikh Ali Jumblatt in Moukhtara, and the latter attempted to reconcile Emir Yusuf with his uncle.[31] Emir Mansur declined Sheikh Ali's mediation. Sa'ad al-Khuri, Emir Yusuf's mudabbir (manager), managed to persuade Sheikh Ali to withdraw his backing of Emir Mansur, while Emir Yusuf gained the support of Uthman Pasha al-Kurji, the governor of Damascus. The latter directed his son Mehmed Pasha al-Kurji, governor of Tripoli, to transfer the tax farms of Byblos and Batroun to Emir Yusuf in 1764.[31] With the latter two tax farms, Emir Yusuf formed a power base in Tripoli's hinterland. Under al-Khuri's guidance and with Druze allies from Chouf, Emir Yusuf led a campaign against the Hamade sheikhs in support of the Maronite clans of Dahdah, Karam and Dahir and Maronite and Sunni Muslim peasants who, since 1759, were all revolting against the Hamade clan.[31] Emir Yusuf defeated the Hamade sheikhs and appropriated their tax farms.[33] This not only empowered Emir Yusuf in his conflict with Emir Mansur, but it also initiated Shihabi patronage over the Maronite bishops and monks who had resented Khazen influence over church affairs and been patronized by the Hamade sheikhs, the Shihab clan's erstwhile allies.[33]

Reign of Yusuf

In 1770, Emir Mansur resigned in favor of Emir Yusuf after being compelled to step down by the Druze sheikhs.[32][33] The transition was held at the village of Barouk, where the Shihabi emirs, Druze sheikhs and religious leaders met and drew up a petition to the governors of Damascus and Sidon, confirming Emir Yusuf's ascendancy.[34] Emir Mansur's resignation was precipitated by his alliance with Sheikh Zahir al-Umar, the Zaydani strongman of northern Palestine, and Sheikh Nasif al-Nassar of Jabal Amil in their revolt against the Ottoman governors of Syria. Sheikh Zahir and the forces of Ali Bey al-Kabir of Egypt had occupied Damascus, but withdrew after Ali Bey's leading commander, Abu al-Dhahab, who was bribed by the Ottomans. Their defeat by the Ottomans made Emir Mansur a liability to the Druze sheikhs vis-a-vis their relations with the Ottoman authorities, so they decided to depose him.[33] Emir Yusuf cultivated ties with Uthman Pasha and his sons in Tripoli and Sidon, and with their backing, sought to challenge the autonomous power of sheikhs Zahir and Nasif.[33] However, Emir Yusuf experienced a series of major setbacks in his cause in 1771.[33] His ally, Uthman Pasha, was routed in the Battle of Lake Hula by Sheikh Zahir's forces. Afterward, Emir Yusuf's large Druze force from Wadi al-Taym and Chouf was routed by Sheikh Nasif's Shia cavalrymen at Nabatieh.[33] Druze casualties during the battle amounted to some 1,500 killed, a loss similar to that suffered by the Yamani coalition at Ain Dara.[33] Furthermore, the forces of sheikhs Zahir and Nasif captured the town of Sidon after Sheikh Ali Jumblatt withdrew.[33] Emir Yusuf's forces were again routed when they attempt oust sheikhs Zahir and Nasif, who had key backing from the Russian fleet, which bombarded Emir Yusuf's camp.[35]

Uthman Pasha, seeking to prevent Beirut's fall to Sheikh Zahir, appointed Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar, who was formerly in Emir Yusuf's service, as garrison commander of the city.[36] Emir Yusuf, as tax farmer of Beirut, agreed to the appointment and declined a bounty on al-Jazzar by Abu al-Dhahab (al-Jazzar was wanted by the Mamluk strongmen of Ottoman Egypt).[36] However, al-Jazzar soon began acting independently after organizing the fortifications of Beirut, and Emir Yusuf appealed to Sheikh Zahir through Emir Mansur's liaising to request Russian bombardment of Beirut and oust al-Jazzar.[36] Sheikh Zahir and the Russians acceded to Emir Yusuf's request after a large bribe was paid to them.[36] After a four-month siege, al-Jazzar withdrew from Beirut in 1772, and Emir Yusuf penalized his Yazbaki allies, sheikhs Abd al-Salam Imad and Husayn Talhuq to compensate for the bribe he paid to the Russians.[36] The following year, Emir Yusuf's brother, Emir Sayyid-Ahmad, took control of Qabb Ilyas and robbed a group of Damascene merchants passing through the village. Emir Yusuf subsequently captured Qabb Ilyas from his brother, and was transferred the tax farm for the Beqaa Valley by the governor of Damascus, Muhammad Pasha al-Azm.[36]

In 1775, Sheikh Zahir was defeated and killed in an Ottoman campaign, and al-Jazzar was installed in Sheikh Zahir's Acre headquarters, and soon after, was appointed governor of Sidon.[36] Among al-Jazzar's principal goals was to centralize authority in Sidon Eyalet and assert control over the Shihabi emirate in Mount Lebanon. To that end, he succeeded in ousting Emir Yusuf from Beirut and removing it from the Shihabi tax farm. Moreover, al-Jazzar took advantage and manipulated divisions among the Shihab emirs in order to break up the Shihabi emirate into weaker entities that he could more easily exploit for revenue.[37] In 1778 he agreed to sell the Chouf tax farm to Emir Yusuf's brothers, emirs Sayyid-Ahmad and Effendi after the latter two gained the support of the Jumblatt and Nakad clans (Emir Yusuf's ally Sheikh Ali Jumblatt died that year).[38] Emir Yusuf, thereafter, based himself in Ghazir and mobilized the support of his Sunni Muslim allies, the Ra'ad and Mir'ibi clans from Akkar.[38] Al-Jazzar restored the Chouf to Emir Yusuf after he paid a large bribe, but his brothers again challenged him 1780.[38] That time they mobilized the support of both the Jumblatti and Yazbaki factions, but their attempt to kill Sa'ad al-Khuri failed, and Effendi was killed.[38] In addition, Emir Yusuf paid al-Jazzar to loan him troops, bribed the Yazbaki faction to defect from his Sayyid-Ahmad's forces and once again secured control of the Shihabi emirate.[38]

Reign of Bashir II

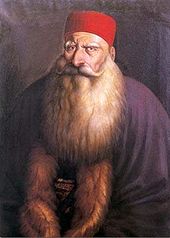

The most prominent among the Shihabi emirs was Emir Bashir Shihab II, who was comparable to Fakhr ad-Din II. His ability as a statesman was first tested in 1799, when Napoleon besieged Acre, a well-fortified coastal city in Palestine, about forty kilometers south of Tyre. Both Napoleon and Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar, the governor of Sidon, requested assistance from Bashir, who remained neutral, declining to assist either combatant. Unable to conquer Acre, Napoleon returned to Egypt, and the death of Al-Jazzar in 1804 removed Bashir's principal opponent in the area.[39] When Bashir II decided to break away from the Ottoman Empire, he allied himself with Muhammad Ali Pasha, the founder of modern Egypt, and assisted Muhammad Ali's son, Ibrahim Pasha, in another siege of Acre. This siege lasted seven months, the city falling on May 27, 1832. The Egyptian army, with assistance from Bashir's troops, also attacked and conquered Damascus on June 14, 1832.[39]

In 1840, four of the principal European powers (Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia), opposing the pro-Egyptian policy of the French, signed the London Treaty with the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman ruler) on July 15, 1840.[39] According to the terms of this treaty, Muhammad Ali was asked to leave Syria; when he rejected this request, Ottoman and British troops landed on the Lebanese coast on September 10, 1840. Faced with this combined force, Muhammad Ali retreated, and on October 14, 1840, Bashir II surrendered to the British and went into exile.[39] Bashir Shihab III was then appointed. On January 13, 1842, the sultan deposed Bashir III and appointed Omar Pasha as governor of Mount Lebanon. This event marked the end of the rule of the Shihabs.

Legacy

Today, the Shihabs are still one of the most prominent families in Lebanon, and the third president of Lebanon after independence, Fuad Chehab, was a member of this family (descending from the line of Emir Hasan, Emir Bashir II's brother[40]) as was former Prime Minister Khaled Chehab. The Shihabs bear the title of "emir". Descendants of Bashir II live in Turkey and are known as the Paksoy family due to Turkish restrictions on non-Turkish surnames.[41] Today, a group of them are Sunni, and others are Maronite Catholics, though they have common family roots. The 11th-century citadel in Hasbaya, South Lebanon, is still a private property of the Shihabs, with many of the family's members still residing in it. Mustafa al-Shihabi, who was born in Hasbaya, served the governor of Aleppo, Syria in 1936-1939.

List of Emirs

| Name | Reign | Religion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emir Bashir I | 1697–1705 | Sunni Muslim | Son of Husayn Shihab of Rashaya and a daughter of Ahmad Ma'n. Acted as regent for Emir Haydar. |

| Emir Haydar | 1705–1732 | Sunni Muslim | Son of Musa Shihab of Hasbaya (d. 1693) and a daughter of Ahmad Ma'n. |

| Emir Mulhim | 1732–1753 | Sunni Muslim | Eldest son of Haydar. |

| Emirs Mansur and Ahmad | 1753–1760 | Sunni Muslims | Sons of Haydar. |

| Emir Qasim | 1760 | ? | Son of Mulhim. |

| Emir Mansur | 1760–1770 | Sunni Muslim | Second reign, during which he ruled without Ahmad. |

| Emir Yusuf | 1770–1778 | Maronite Christian | Son of Mulhim. |

| Emirs Sayyid-Ahmad and Effendi | 1778 | ? | Sons of Mulhim. |

| Emir Yusuf | 1778–1789 | Maronite Christian | Second reign. |

| Emir Bashir II | 1789–1794 | Maronite Christian | Son of Umar, who was a son of Haydar. |

| Emirs Husayn and Sa'ad ad-Din | 1794–1795 | Maronite Christians | Young sons of Yusuf. Real power held by their Maronite manager Jirji al-Baz. |

| Emir Bashir II | 1795–1799 | Maronite Christian | Second reign. |

| Emirs Husayn and Sa'ad ad-Din | 1799–1800 | Maronite Christians | Second reign. |

| Emir Bashir II | 1800–1819 | Maronite Christian | Third reign. |

| Emirs Hasan and Salman | 1819–1820 | Sunni Muslims | Members of the Rashaya-based branch of the Shihab family. |

| Emir Bashir II | 1820–1821 | Maronite Christian | Fourth reign. |

| Emirs Hasan and Salman | 1821 | Sunni Muslims | Second reign. |

| Emir Abbas | 1821–1822 | Sunni Muslim | Son of As'ad, who was a paternal grandson of Haydar. |

| Emir Bashir II | 1822–1840 | Maronite Christian | Fifth reign. |

| Emir Bashir III | 1840–1842 | ? | Son of Qasim. Mount Lebanon Emirate abrogated. |

References

- ^ a b Hitti, Philipp K. (1928). The Origins of the Druze People: With Extracts from their Sacred Writings. AMS Press. p. 7.

- ^ Mishaqa, ed. Thackston 1988, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Abu Izzeddin 1998, p. 201.

- ^ Winter 2010, p. 128.

- ^ Hourani 2010, p. 968.

- ^ Hourani 2010, p. 969.

- ^ Hourani 2010, pp. 969–970.

- ^ Hourani 2010, p. 970.

- ^ Abu-Husayn 2004, p. 24.

- ^ a b Hourani 2010, p. 971.

- ^ Hourani 2010, pp. 971–972.

- ^ Abu-Husayn 1985, p. 25.

- ^ Abu-Husayn 1985, p. 88.

- ^ Abu-Husayn 1985, p. 93.

- ^ a b Hourani 2010, p. 972.

- ^ a b c d Harris 2012, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Khairallah, Shereen (1996). The Sisters of Men: Lebanese Women in History. Institute for Women Studies in the Arab World. p. 111.

- ^ Harris 2012, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b c d e Harris 2012, p. 110.

- ^ Harris 2012, p. 111.

- ^ a b c d e Harris 2012, p. 113.

- ^ a b Abu Izzeddin 1998, p. 202.

- ^ Abu Izzeddin 1998, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris, p. 114.

- ^ a b Harris 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Harris 2012, pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris 2012, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d Harris, p. 116.

- ^ Harris, p. 117.

- ^ a b Harris, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Harris, p. 119.

- ^ a b c d e Abu Izzeddin, p. 203.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harris, p. 120.

- ^ Abu Izzeddin, pp 203–204.

- ^ Harris, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harris, p. 122.

- ^ Harris, pp. 122–123.

- ^ a b c d e Harris, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d Library of Congress - The Shihabs, 1697-1842

- ^ Malsagne, Stéphane (2011). Fouad Chéhab (1902-1973). Une figure oubliée de l'histoire libanaise (in French). Karthala Editions. p. 45. ISBN 9782811133689.

- ^ "Bachir 2 Shihab Chehab".

Bibliography

- Abu-Husayn, Abdul-Rahim (1985). Provincial Leaderships in Syria, 1575-1650. Beirut: American University of Beirut. ISBN 9780815660729.

- Abu-Husayn, Abdul-Rahim (2004). The View from Istanbul: Lebanon and the Druze Emirate in the Ottoman Chancery Documents, 1546–1711. Oxford and New York: The Centre for Lebanese Studies and I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-856-8.

- Abu Izzeddin, Nejla M. (1993). The Druzes: A New Study of Their History, Faith, and Society. Brill. ISBN 9789004097056.

- Harris, William (2012). Lebanon: A History, 600-2011. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195181111.

- Hourani, Alexander (2010). New Documents on the History of Mount Lebanon and Arabistan in the 10th and 11th Centuries H. Beirut.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mishaqa, Mikhail (1988). Thackston, Wheeler McIntosh (ed.). Murder, Mayhem, Pillage, and Plunder: The History of the Lebanon in the 18th and 19th Centuries by Mikhayil Mishaqa (1800-1873). State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780887067129.