Africa–China economic relations

| The People's Republic of China and Africa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2023) |

Economic relations between China and Africa, one part of more general Africa–China relations, began in the 7th century and continue through the present day. Currently, China seeks resources for its growing consumption, and African countries seek funds to develop their infrastructure.

Large-scale projects, often accompanied by a soft loan, are proposed to African countries rich in natural resources. China commonly funds the construction of infrastructure such as roads and railroads, dams, ports, and airports. Sometimes, Chinese state-owned firms build large-scale infrastructure in African countries in exchange for access to minerals or hydrocarbons, such as oil.[1] In those resource-for-infrastructure contracts, countries in Africa use those minerals and hydrocarbons directly as a way to pay for the infrastructure built by Chinese firms.[1]

While relations are mainly conducted through diplomacy and trade, military support via the provision of arms and other equipment is also a major component.[2] In the diplomatic and economic rush into Africa, the United States, France, and the UK are China's main competitors. China surpassed the US in 2009 to become Africa's largest trading partner. Bilateral trade agreements have been signed between China and 40 countries of the continent. In 2000, China Africa Trade amounted to $10 billion and by 2014, it had grown to $220 billion.[3]

History of Sino-African relations

Early dynasties (700 a.d. to 1800)

There are traces of Chinese activity in Africa dating back from the Tang dynasty. Chinese porcelain has been found along the coasts of Egypt in North Africa. Chinese coins dated 9th century,[4] have been discovered in Kenya, Zanzibar, and Somalia. The Song dynasty established maritime trade with the Ajuran Empire in the mid-12th century. The Yuan dynasty's Zhu Siben made the first known Chinese voyage to the Atlantic Ocean,[4] while the Ming dynasty's admiral Zheng He and his fleet of more than 300 ships made seven separate voyages to areas around the Indian Ocean and landed on the coast of Eastern Africa.[4]

Ancient Sino-African official contacts were not widespread. Most Chinese emissaries are believed to have stopped before ever reaching Europe or Africa, probably travelling as far as the far eastern provinces of the Roman and later Byzantine empires. However, some did reach Africa. Yuan dynasty ambassadors, which was one of only two times when China was ruled by a foreign dynasty, this one the Mongols, traveled to Madagascar. Zhu Siben traveled along Africa's western coasts, drawing a more precise map of Africa's triangular shape.

Between 1405 and 1433, the Yongle Emperor of the Ming dynasty sponsored a series of naval expeditions, with Zheng He as the leader. He was placed in control of a massive fleet of ships, which numbered as much as 300 treasure ships with at least 28,000 men.[5] Among the many places traveled, which included Arabia, Somalia, India, Indonesia and Thailand, His fleet traveled to East Africa. On their return, the fleet brought back African leaders, as well as lions, rhinoceros', ostriches, giraffes, etc., to the great joy of the court.[4]

Following the Yongle Emperor's death, and the resurgence of Confucianism, which opposed frivolous external adventures, such expensive foreign policies were abandoned, and the costly fleet was destroyed.[4] Confucian officials preferred agriculture and authority over innovation, exploration, and trade. Their opinion was that Ming China had nothing to learn from overseas barbarians.[4]

The modern Chinese version is that the European mercantilism in the Age of Discovery aggressively ended Sino-African relations.[4][6]

Industrial era (1800 to 1949)

A new era of Chinese trade began in the industrial era. European colonization of Africa and the abolition of slavery in France caused major workforce shortages in European colonies. Europe looked for a way to fill the gap with low-cost workers from abroad, namely India and China. Beginning in the 1880s, tens of thousands of Chinese Coolies were sent overseas to work in the mines, railroads, and plantations of the colonial powers.[4] The exploitation of inland resources, such as copper mines, also led to the presence of relatively large, isolated Chinese populations in landlocked countries such as Zambia. Jean Ping, the minister of Foreign Affairs of Gabon, who presided the UN Assembly, was born from an African mother and a Chinese father in Gabon, a country where almost no Chinese were present.[7]

Diplomatic opening (1949 to 1980)

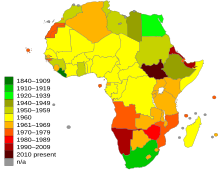

After the formation of the People's Republic of China following the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) victory in 1949, some Chinese fled, eventually landing in Africa.[8] By the 1950s, Chinese communities in excess of 100,000 existed in South Africa, Madagascar, and Mauritius[9] Small Chinese communities in other parts of Africa later became the cornerstone of the post-1980 growth in dealings between China and Africa. However, at the time, many lived lives centered on local agriculture and probably had little or no contact with China.[citation needed] Precise statistics of the Chinese presence in Africa are difficult to obtain, since both Chinese and African offices have remained discreet about this issue.[10]

The newly formed People's Republic of China actively began supporting the decolonization movements in Africa and the Pacific. This era is especially important in the "Sino-African friendship" movement, as both the PRC and many of the decolonized African nations shared a "victim background", the perception that they were both taken advantage of by imperialistic nations such as Japan and European states.[11]

The growing Sino-Soviet split of the 1950s and 1960s allowed the PRC to get US support, and to return to the international scene in 1971.[11] China (Taiwan)'s seat on the Security Council was expelled by General Assembly Resolution 2758, and replaced in all UN organs with the People's Republic of China.

With growing opposition between the USSR and the PRC in the 1960s, China expanded its own program of diplomacy, sometimes supporting capitalist factions against USSR backed ones (e.g. Angola (UNITA) and South Africa Apartheid).[12]

At the 1955 Bandung conference, China showed an interest in becoming one of the leaders of the "third world". Zhou Enlai made an extensive African tour between 1963 and 1964, to strengthen Sino-African friendship. Hundreds of Chinese medics were sent to Africa and infrastructural projects were planned. The iconic 1860 km Tanzam railroad, built by 50.000 Chinese workers, was completed in 1976.[11] Ex-diplomat and now professor of Foreign Relations in Beijing, M. Xinghua, referred to this era as the "golden age" of Sino-African relations.[12] Growing numbers of African countries switched their recognition from the ROC (Taiwan) to the PRC. 1976 marked the death of Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong, bringing the era of ideology symbolically to a close and leaving power in the pragmatic hands of Deng Xiaoping.

The shift to a less ideological approach was not without difficulty, and it involved considerable political effort to maintain the perception of a coherent national direction. Writer Philip Snow describes it thus: "a continual attempt to sustain a rhetorical unity which has sometimes disguised the pursuit of profoundly different goals".[13]

Economic acceleration (1980 to the present)

As China awakened from its decades-old period of semi-isolation, the country was boosted by internal reforms, growing Taiwanese and foreign investments, and the dramatic expansion of its workforce. China once more turned toward Africa, now looking to the continent both a source of key resources and as a market for its low-cost consumer goods.[14]

Writer R. Marchal identifies two key events in Sino-African relations. First, the Tian'anmen protests in 1989; the spectacle consolidated opposition to what was perceived as the PRC's violent oppression of demonstrators. Economically developed nations threatened to enforce economic sanctions, while African countries kept silent, either to conceal their own harsh policies or to further their ties with China. Indeed, that was the results as China's strengthened its cooperation with African states.[14] The growing alliance between China and Africa was largely needed for both sides. China's growing industry resulted in a rapidly expanding and seemingly inexhaustible demand for resources.[14] Meanwhile, in the relative calm ushered in by the end of the cold war, concerns about human rights issues in China, furthered isolated the mix of rogue and pariah states.

| ||

| 走 Zǒu |

出 chū |

去. qū。 |

In 1995, Jiang Zemin pushed the pace of economic growth even faster. Under his leadership, China pursued broad reforms with confidence. Zemin declared to Chinese entrepreneurs, "Go out" (走出去 Zǒu chūqū), encouraging businessmen to enter world markets[14] In the late 1990s, Chinese bids were heavily supported by the government and local embassies, with government-owned Exim Bank of China providing needed finances at low rates. The advantages provided by the PRC allowed Chinese enterprises to win many bids on the world market.[14]

PRC officials described the period as a "sane adjustment" and the "sane development of economic and commercial Sino-African relations".[14] Still, Chinese and African diplomacy continued to invoke the imagery of the past ideological period: the shared history of victimization at the hands of 19th century Westerners and the common fight for autonomy and independence.[14] To those, China added the fight toward progress in a world unfairly dominated by western powers. It is worth noting that in Africa today, strongly government-backed Chinese companies are equally or more successful than many western companies.[citation needed]

International relations analyst Parag Khanna states that by making massive trade and investment deals with Latin America and Africa, China established its presence as a superpower along with the European Union and the United States. China's rise is demonstrated by its ballooning share of trade in its gross domestic product. Khanna believes that China's consultative style has allowed it to develop political and economic ties with many countries including those viewed as rogue states by western diplomacies.[15]

| Country | Chinese |

|---|---|

| Angola | 30.000 |

| South Africa | 200.000 |

| Sudan | 20–50.000 |

| Congo-Brazzaville | 7.000 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 8.000 |

| Gabon | 6.000 |

| Nigeria | 50.000 |

| Algeria | 20.000 |

| Morocco | / |

| Chad | hundreds |

| Egypt | thousands |

| Ethiopia | 5–7.000 |

| RDC | 10.000 |

| Zambia | 40.000 |

| Zimbabwe | 10.000 |

| Mozambique | 1.500 |

| Niger | 1.000 |

| Cameroon | 7.000 |

| Gabon | 6.000 |

| Total | +500.000 |

China's rise in the world market led the Chinese diaspora in Africa to make contact with relatives in their homeland. Renewed relations created a portal through which African demand for low-price consumers goods could flow.[17] Chinese businessmen in Africa, with contacts in China, brought in skilled industrial engineers and technicians such as mechanics, electricians, carpenters, to build African industry from the ground up.[18]

The 1995 official Go Global declaration and the 2001 Chinese entry into the WTO paved the way for private citizens in China to increasingly connect with, import from, and export to the budding Sino-African markets.

Expansion of military presence (1990 to the present)

Africa does not stand at the center of China's security strategies, yet the continent has been and remains a major source for China's commodity stocks. Africa was also seen as an important bid for international legitimacy against the eastern and western blocks. In the 1960s, China contributed to Africa's military power by assisting and training liberation groups, such as Mugabe's ZANU. In 1958, China quickly recognized Algeria's National Liberation Front and provided the new government with small weapons. In 1960, it provided training to the rebels in Guinea-Bissau. In Mozambique, the FRELIMO received guerilla training and weapons from China. During the 1960-1970s, China provided military training and weapons to any African country that was not already supported by the Soviet Union. Some military assistance turned out to be failures: After supporting Angola's MPLA, the Chinese authorities switched sides and began supporting UNITA, which never managed to fully grasp power in the country. From 1967 to 1976, China transferred $142 million in arms to Africa (Congo-Brazzaville, Tanzania and Zaire being the major recipients). During the 1980s, China's sales of arms to African countries dropped significantly.[19]

The Chinese military presence in Africa has increased since 1990 when China agreed to join in UN peace-keeping responsibilities.[20] In January 2005, 598 Chinese peace keepers were sent to Liberia. Others were sent to Western Sahara as part of Operation MINURSO,[21] Sierra Leone, the Ivory Coast and the DRC.[20] This was a carefully handled and largely symbolic move, as China did not want to appear as a new colonialist power overly interfering in internal affairs.

China has put its weight behind the conflict in Chad. The FUC rebellion, based in Sudan and aiming to overthrow the pro-Taiwan ruler of Chad, Idriss Déby, has received Chinese diplomatic support as well as light weapons and Sudanese oil. With Sudan maintaining a pro-Chinese stance, and Chad being pro-Taiwan (and since 2003, an oil producer), China has pursued their interests in replacing Deby with a more pro-China leader. The 2006 Chadian coup d'état attempt failed after French intervention, but Deby then switched his support to Beijing, with the apparent defeat becoming a strategic victory for China.[20]

China currently has military alliances with 6 African states, 4 of which are major oil suppliers: Sudan, Algeria, Nigeria and Egypt.[20] On the whole, however, China's influence remains limited,[22] especially when compared with Western powers such as France, whose military involvement in the 2004 Ivory Coast conflict and the 2006 Chad conflict was significant. China is particularly unable to compete with the ex-colonial powers in providing military training and educational programs, given the latter's continuing ties via military academies like Sandhurst in the UK and Saint Cyr in France.[22]

In 2015, despite growing economic interests in Africa, China has not yet settled any military base on the continent. However, with a naval logistics center is planned to be built in Djibouti raises questions about China's need to set military bases in Africa. China's increasing reliance on Africa's resources warrants it to hold a stronger military position.[23]

Effects of the global economic downturn (2007 to the present)

The Chinese have changed their strategy

— Ibrahima Sory Diallo, a senior economist in Guinea's Ministry of Finance

Since 2009, a switch has been noticed in China's approach to Africa. The new tack has been to underline long-term stability in light of the worldwide economic crisis.[24]

Some major projects get stopped, such as in Angola, where 2/3 of a US$4 billion CIF fund disappeared, it is unclear where this money went.[25][26] Following this, a major Chinese-backed oil refinery project was scrapped by Angolan officials, with unclear reasons, causing problems for Sino-Angolan relations.[26]

As raw material prices fall through the global recession, the negotiating position of African countries is sharply weakened, while expected profits intended to repay Chinese loans are collapsing. As a consequence, tensions have increased: China is more worried about the risk of default, while African countries fear servicing their debt over the long term of their loans.

At the dawn of the 21st century, while Africa suffered from China's withdrawal, it is less dependent of external powers to build a self-reliable economy.[27]

Political and economic background

China

The People's Republic of China began to pursue market socialism in the 1970s under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping. This marked the change to capitalist practices as the foundation of the PRC's socioeconomic development, a process initiated several decades earlier following the aftermath of the Great Leap Forward. Beginning in 1980, the PRC initiated a policy of rapid modernization and industrialization, resulting in reduced poverty and developing the base of a powerful industrial economy. As of 2018, the PRC had the second largest nominal GDP in the world, at $13.456 trillion, and the largest GDP by purchasing power parity at $23.12 trillion.[28][29] Today, the PRC faces a growing shortage of raw materials such as oil, wood, copper, and aluminum, all of which are needed to support its economic expansion and the production of manufactured goods.

Africa

The continent of Africa has a population of roughly 1.216 billion[30] and a surface of 30,221,532 km2. Industrialization started marginally in the early 20th century in the colonies of the European nations, namely Portugal, Belgium, Spain, Germany, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom. The continent's various wars for independence brought on the violent and disruptive division of Africa. Africa, being a major source of raw materials, saw the colonial powers vie for influence among the newly independent nations, with former colonial powers establishing special relations with their former colonies, often by offering economic aid and alliances for access to the vast resources of their former territories.

Today, the presence of diamonds, gold, silver, uranium, cobalt and large oil reserves have brought Africa to the forefront of industrial development, with many of the world's economic powers building relations with Africa's resource rich nations.

As of 2008, the entire GDP of Africa was about $1.2 trillion.[28]

Incentives for cooperation

Both China and Africa proclaim a new, mutually beneficial economic, political, and regional alliance. China sees a source for raw materials and energy, desperately needed to support its industrial and economic growth. Success in this quest means high employment and a higher quality of life for Chinese citizens, as well as increasing social stability and political security for Chinese elites.

Chinese oil companies are gaining the invaluable experience of working in African nations which will prepare them for larger projects on the far more competitive world market. The efficiency of Chinese assistance, loans, and proposals generally been praised. Finally, Chinese industry has found in Africa a budding market for its low-cost manufactured goods.

Chinese diaspora in Africa have been actively supported by Chinese embassies, continuously building the 'Blood Brother' relation between China and Africa as perceived victims of Western imperialism.[31]

African leaders earn legitimacy through Chinese partnerships. They work together with the Chinese to provide Africa with key structural infrastructure—roads, railways, ports, hydroelectric dams, and refineries—fundamentals which will help Africa avoid the "resource curse". Success in this endeavor means avoiding the exploitation of their natural wealth and the beginning of fundamental social and economic transformations on the continent.[32]

African countries partnering with China today are signing with a future world superpower. In Africa, this Chinese alliance provides strong psychological consequences. It provides economic hope and shows African elites an example of success which they may take as exemplars of their own future. Writer Harry Broadman commented that if Chinese investments in key sectors of infrastructure, telecommunication, manufacturing, foods, and textiles radically alter the African continent, the main change will have taken place in African minds.[33] With the recent growth and economic improvement, more Africans students are returning to Africa after studies abroad to bring their skills and industry home.

Education in China

Development Reimagined reports that China hosted 74,011 students from 24 African countries in 2017 thanks to overall growth of 258% from 2011 to 2017. By 2017, the top African student population are from Ghana, Nigeria, Mauritius, Kenya and Sudan.[34]

In 2018, the Chinese government announced at the triennial Forum on China-Africa Cooperation that China would increase its scholarship offerings to African students from 30,000 in 2015 to 50,000. According to the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China, 81,562 African students studied in China in 2018, a 770% increase compared to 1996. China is now the second largest African student-hosting country behind France.[35]

In 2020, according to UNESCO's Global Annual Education Report, China offered 12,000 university scholarships to African students for the next academic year, to support their studies at Chinese universities.[36]

By 2022, China is predicted to host more Nigerians than either the UK or the US.[34]

Overview of trade

| Year | World[38] | Africa[39] | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 620.8 | 12 | 1.9% |

| 2003[21] | 851.2 | 18.48 | 2.17% |

| 2005 | 1422 | 39 | 2.74% |

| 2006 | 1760.6 | 55 | 3.12% |

| 2007 | 2173.8 | 73.6 | 3.38% |

| 2010 | ? | 100? | ? |

| Year | Africa to China[40] (year increase) |

China to Africa[41] (year increase) |

Sum (year increase) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 15.65 | 13.82 | 29.47 |

| 2005 | 21.12 | 18.69 | 39.81 (+35) |

| 2006 | 28.77 | 26.70 | 55.47 (+39.3) |

| 2007 | 36.33 (+25.9%) | 37.31 (+39.7%) | 73.644 (+32.7%) |

Chinese world trade has grown rapidly over the last decades. Total trade was roughly $100 US billion in 1990, 500 billion in 2000, 850 billion in 2004, 1400 billion in 2005, and 2200 billion in 2007. That computes to an over 20-fold increase in under 20 years and an annualized growth rate of nearly 18%. More remarkably, the vast majority of China's growth has taken place in the past decade; in other words, not only is the size of China's trade growing, the rate of the growth is accelerating. Thanks to the decades-old Chinese diaspora, the economic dynamism of PRC embassies, China's low-cost manufacturing industry, an efficient export engine, and an exchange rate that until 2010 has been held deliberately low, China's global trade has thrived.[22]

Its economic interests in Africa have increased dramatically since the 1990s.[42] The most prominent Chinese corporate actors are state-owned enterprises.[42] The majority of Chinese economic activity in Africa is in the sectors of energy, mining, construction, telecommunications, and finance.[42]

In context of China's total trade, Africa actually comprises only a small part. In 2007, Sino-African trade rose $73b, 3.4% of China's $2173b total, far lower than the EU ($356b, 16.4%), the USA ($302b, 13.9%), and Japan ($236b, 10.9%).[43]

China is Africa's first trading partner since it surpassed the United States in 2009.[44]

Chinese exports to Africa

The Chinese diaspora first reactivated its familial links to import low-priced goods such cups, forks, cellular phone, radio, television sets and umbrellas to Africa[45] Indeed, the response by African consumers was fairly positive and receptive to the large quantity of affordable goods imported from China. China's imported goods were offered at a lower price and at a better quality in comparison to the goods offered by African companies. Cheap Chinese clothes,[46] and cheap Chinese cars at half the price of western ones allow African customers to suddenly raise up the purchasing power.[47]

| Country | to China | from China | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa | 2.02 | 1.84 | 3.86 |

| Angola | 0.14 | 2.2 | 2.34 |

| Sudan | 0.47 | 1.44 | 1.91 |

| Nigeria | 1.78 | 0.07 | 1.85 |

| Egypt | 0.93 | 0.15 | 1.08 |

| Congo-Brazzaville | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.87 |

| Morocco | 0.69 | 0.16 | 0.85 |

| Algeria | 0.64 | 0.09 | 0.73 |

| Benin | 0.47 | 0.07 | 0.54 |

| Others | 2.93 | 1.52 | 4.45 |

| Total | 10.13 | 8.35 | 18.48 |

In Africa, China may sell its own low quality or overproduced goods and inventory,[21] a key outlet which helps maintain China's economic and social stability. Chinese shop-owners in Africa are able to sell Chinese-built, Chinese-shipped goods for a profit. A negative consequence of China's low-cost consumer goods trade is that it only goes one way. China does not purchase manufactured products from Africa,[48] while cheap Chinese imports flood the local marketplace, making it difficult for local industries to compete.[49] Also cheap Chinese manufactures have resulted in the collapse of some African shops yet increased the purchasing power of poor African consumers.[50]

A noticeable case is the Chinese textile industry. In many countries, textiles are one of the first manufacturing industries to develop, but the African textile industry has been crippled by competition[22] The negative consequences are not easily resolved: African consumers give praise to Chinese textiles, and they are often the first clothes they can afford to buy new; yet local manufactures are badly wounded, raising opposition and concern over the loss of local jobs.

Africa is seen by Chinese businessmen as 900 million potential customers in a fast-growing market.[21] Perhaps more importantly, African societies are far from market saturation, like their Western counterparts. Thus, in Africa, China finds not only an ample supply of potential new customers but far less competition from other nations.

A few examples of the products imported by China in African countries in 2014: Benin bought $411m worth of wigs and fake bears from China, 88% of South Africa's imported male underpants were from China, Mauritius spent $438,929 on Chinese soy sauce, Kenya spent $8,197,499 on plastic toilet seats, Nigeria spent $9,372,920 on Chinese toothbrushes, Togo bought $193,818,756 worth of Chinese motorbikes and Nigeria $450,012,993.[51]

African exports to China

In the other direction, China's growing thirst for raw materials led Chinese state-owned enterprises to the country with natural resources, such as wood and minerals (like those from the Gabonese forests). By the end of the 1990s, China had become interested in African oil, too.

Over time, African laws adapted to China's demand, laws intended to force the local transformation of raw materials for export. This led to a new kind of manufacturing in Africa, managed by the Chinese, with African workers producing exports for Chinese, as well as European, American and Japanese customers.[45] African leaders have pursued an increase of the share of raw material transformation both to add value to their exports and to provide manufacturing jobs for local Africans.

China's oil purchases have raised oil prices, boosting the government revenues of oil exporters like Angola, Gabon and Nigeria, while hurting the other oil-importing African countries. At the same time, China's raw materials purchases have increased prices for copper, timber, and nickel, which benefits many African countries as well.[22]

While African growth from 2000 to 2005 averaged 4.7% per year, almost twice the growth has come from petroleum-exporting countries (2005: 7.4%; 2006: 6.7%; 2007: 9.1%) than from petroleum-importing countries (2005: 4.5%; 2006: 4.8%; 2007: 4.5%).[52]

During the year 2011, trade between Africa and China increased a staggering 33% from the previous year to US$166 billion. This included Chinese imports from Africa equalling US$93 billion, consisting largely of mineral ores, petroleum, and agricultural products and Chinese exports to Africa totalling $93 billion, consisting largely of manufactured goods.[53] Outlining the rapidly expanding trade between the African continent and China, trade between these two areas of the world increased further by over 22% year-over-year to US$80.5 billion during the first five months of the year 2012.[53] Imports from Africa were up 25.5% to $49.6 billion during these first five months of 2012 and exports of Chinese-made products, such as machinery, electrical and consumer goods and clothing/footwear increased 17.5% to reach $30.9 billion.[53] China remained Africa's largest trading partner during 2011 for the fourth consecutive year (starting in 2008). To put the entire trade between China and Africa into perspective, during the early 1960s trade between these two large parts of the world were in the mere hundreds of millions of dollars back then. Europe dominated African trade during these formative years of European decolonization process in the African continent. Even as early as the 1980s, trade between China and Africa was minuscule. Trade between China and Africa largely grew exponentially following China's joining of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the opening up of China to emigration (of Chinese people to Africa) and the free movement of companies, peoples, and products both to and from the African continent starting from the early 2000 onwards.

As of at least 2023, African waters are an important source of seafood for China.[54]: 335

Agricultural connections

Since the mid-1990s, China has encouraged its agricultural enterprises to seek economic opportunities abroad as part of its go out policy, including to Africa.[55]: 188 Chinese policy guidance has specifically encouraged such efforts in rubber, oil palm, cotton, vegetable cultivation, animal husbandry, aquaculture, and assembly of agriculture machines.[55]

Agricultural Technology Demonstration Centers are a highly visible component of China's agricultural cooperation with African countries.[56] The function of these centers is to transmit agricultural expertise and technology from China to developing countries in Africa while also creating market opportunities for Chinese companies in the agricultural sector.[56] China is motivated to establish these centers out of both an ideological commitment to fostering South-South cooperation and sharing its experience with less developed countries and by a pragmatic desire to increase its long-term food security.[57] Assessing China's ideological motivations in this area, Professor Dawn C. Murphy states, "China's commitment to assisting African countries in establishing their food security and raising their living standards appears to be constant since the 1950s."[55]

Agricultural Technology Demonstration Centers receive three years of grant support from China's Ministry of Commerce.[56] Depending on the consent of the host country, Chinese enterprises or province level agricultural institutes operate a center for an additional five to eight years before transferring them to the host government.[56]

China first announced its Agricultural Technology Demonstrations Centers at the 2006 meeting of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. It launched 19 of these centers between 2006 and 2018, all in sub-Saharan Africa.[56] As of 2023, Agricultural Technology Demonstration Centers exist in 24 African countries.[54]: 173

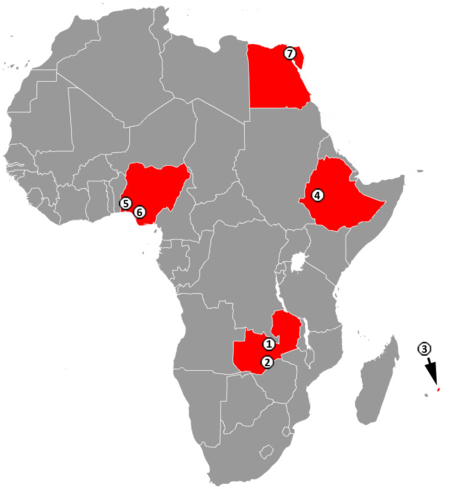

Infrastructure

1: Chambishi, Zambia – copper and copper related industries.[58][59]

2: Lusaka, Zambia – garments, food, appliances, tobacco and electronics. Is classified as a subzone of the Chambishi zone. Completed in 2009.[58][60]

3: Jinfei, Mauritius – manufacturing (textiles, garments, machinery, high-tech), trade, tourism and finance.[58][61]

4: Oriental, Ethiopia – electrical machinery, construction materials, steel and metallurgy.[58]

5: Ogun, Nigeria, – construction materials, ceramics, ironware, furniture, wood processing, medicine, and computers.[58]

6: Lekki, Nigeria – transportation equipment, textiles, home appliances, telecommunications, and light industry.[58]

7: Suez, Egypt – petroleum equipment, electrical appliance, textile and automobile manufacturers. Completed in October 2010[62][needs update]

For years, business in Africa was hampered by poor transportation between countries and regions.[63] Chinese-African associations have worked towards ending this unproductive situation. China provides infrastructure funding and workforce in exchange for immediate preferential relations including lower resource prices or shares of African resources. As a secondary effect, this infrastructure allows Africa to increase its production and exports, improve the quality of life and increase the condition of millions of Africans, who will one day become as many millions of potential buyers of Chinese goods.

The recent Sino-Angolan association is illustrative. When a petroleum-rich area called for investment and rebuilding, China advanced a $5 billion loan to be repaid in oil. They sent Chinese technicians, fixing a large part of the electrical system, and leading a part of the reconstruction. In the short term Angola benefits from Chinese-built roads, hospitals, schools, hotels, football stadiums, shopping centers and telecommunications projects.[64][65] In turn, Angola mortgaged future oil production of a valuable, non-renewable resource. It may turn out to be a costly trade for Angola, but their needs for infrastructure is immediate and that is precisely what China provides when no one else is willing to do so. And thusly, Angola has become China's leading energy supplier.[65]

Special economic zones

China has established special economic zones in Africa, zones where "the Chinese government will create the enabling environment into which Chinese companies can follow".[63] Generally, the Chinese government takes a hands-off approach, leaving it to Chinese enterprises to work to establish such zones (although it does provide support in the form of grants, loans, and subsidies, including support via the China Africa Development Fund).[55]: 177 Such zones fall within the Chinese policy to go out and compete globally.[55]: 182

The first Chinese overseas SEZs facilitated the offshoring of labor-intensive and less competitive industries, for example in textiles.[55]: 177 As Professor Dawn C. Murphy summarizes, these zones now "aim to transfer China's development successes to other countries, increase business opportunities for China manufacturing companies, avoid trade barriers by setting up zones in countries with preferential trade access to important markets, and create a positive business environment for Chinese small and medium-sized enterprises investing in these regions."[55]: 177 Overseas SEZs also foster support for China in the international system and help advocate for developing country causes through South-South cooperation.[55] They "help China demonstrate it is acting as a responsible great power in these regions."[55]

Chinese banks

The Exim Bank of China (Eximbank) is a government bank under direct leadership of the State Council, acting both in China and overseas. For its oversea actions, EximBank has hundreds of offices across the world, with three key representatives in Paris, St. Petersburg, and Johannesburg.[66] The bank is a major force in Chinese foreign trade, aiming to catalyze import-export initiatives.

Eximbank offers enterprises and allies a complete set of financial products. Low-rate loans and associations with skilled Chinese building companies are guided towards building or rebuilding local infrastructure, equipment, and offshore stations which meet a dual Chinese and African interest.[66] EximBank can provide loans for roads, railroads, electric and telecommunication systems, pipelines, hospitals and various other needed facilities. It is the sole lending bank for Chinese Government Concessional Loans entrusted by the Chinese Government.

The bank officially aims to promote the development of Chinese export-oriented economy, to help provide China with raw materials, and facilitate the selling of Chinese goods abroad .[66] EximBank helps to invest in underdeveloped African countries, allowing them to both produce and export more raw materials to Chinese industries, and to allowing African societies to expand their own markets.[66] In 2006, EximBank alone pledged $20 billion in development funds for 2007 through 2010, more than all western funding. Several other Chinese bank also provide African governments and enterprises with similar agreements. China has shown itself to be more competitive, less bureaucratic, and better adapted to doing business in Africa.[47] Between 2009 and 2010 China Development Bank (CDB) and Eximbank publicly offered around US$110 bn worth of loans to emerging markets. Beating the World Bank's record of offering just over US$100 bn between 2008 and 2010.[67]

Chinese embassies

The Chinese government helps, "by all possible means", providing information, legal counsel, low-rate loans, and upon return to China, cheaper land in return for all the services provided to the Chinese nation in Africa."[68] PRC embassies are full-time supporters of Chinese economic progress in Africa, widely using the numerous and well-organized pioneer Chinese businessmen of the diaspora. The Chinese government, well informed by these local businessmen about regional conditions, is equipped with thousands of skilled engineers and workers ready to leave China, as well as by experienced banks (i.e. EximBank) and large reserves of US dollars (as of 2008: approximately 1.4 trillion).[69] The Chinese government is thus ready for taking on large-scale investments and projects, and if approved, to lead them to completion.

In pursuing economic progress in Africa, the Chinese diaspora and Chinese producers have been actively assisted by PRC embassies. Michel and Beuret note that PRC embassies and local Chinese businessmen have frequent meetings and actively provide mutual assistances and information. For Africans requesting PRC Visas for China, the embassy may request further information about the local businessmen often about his wealth. When confirmed, the African businessmen or consumer quickly gets a Visa agreement.[citation needed]

Large infrastructure projects

- Nigeria: railway Lagos-Kano, US$8.3b, 11,000 Chinese workers; Mambilla plateau, 2.600 MW hydro-electric central ;[10]

- Angola and Zambia: the vital Benguela railway line built with the British and linking Zambia and RDC's copper mines to Angola's Atlantic port of Lobito, was to be rebuilt by the Chinese company CIF (the project was canceled after US$3b disappeared). China is the world largest consumer of copper;[63][70]

- Guinea: 2006, a free of charge industrial 'package' including: one mine, one dam, one hydroelectric central, one railway, and one refinery was proposed to the Guinea bauxite/aluminum industry by China, funded by the Exim Bank of China, which will get repaid by purchasing alumina at a preferential price.[71]

- Algeria: a 1,000 km freeway built by Chinese workers.[72]

- Tanzania and Zambia: decades ago, the 1860 km Tazara railway is completed in 1976, with 47 bridges and 18 tunnel made by 50,000 Chinese workers.[73]

- Sudan: pipeline and oilfields; Port Sudan completed within 2 years.[63]

- Congo: barrage d'Imboulou.[74]

Railway projects past and present

Arms

Chinese arms show up across the African continent from Liberia to Somalia. The People's Liberation Army (PLA) was allowed to sell weapons in the 1980s and created several export enterprises, most notably, Norinco, Xingxing, and Poly Group, which have sold weapons to rogue states such as Sudan and Zimbabwe, while Chinese weapons were used in Congo, Tanzania, Rwanda, Chad, and Liberia.[20]

These trades appear to be mostly small arms sales to middlemen arms dealers who in turn sell to both governments and rebels in Africa. The available evidence suggests these amounts are not major, especially compared to the U.S. supply of nearly 50% of the world's weapons, and that the direct leverage of the Peoples Liberation Army or the civilian ministries is modest in most African conflicts. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimates China's 2000–2004 unpublished arms exports at about $1.4b, and US exports at about $25.9b. A 2005 UN arms destruction operation in Congo reported that 17% of them were Chinese made, while the remaining 83% came from other manufacturers.[20] China also disagrees to sell weapons to unrecognized countries. According to Dr. Wilson, on the whole, arms sales have been the least significant factor relative to other instruments of China's statecraft.[22]1

On the other hand, Chinese arms supplies may be underestimated, both because part of these weapons come to Africa via indirect ways, or through uncounted exchanges of arms for raw materials, or because Chinese sales numbers are biased downwards. In Liberia, from 2001 to 2003, against a UN weapon embargo, Chinese weapons were purchased by Van Kouwenhoven, from the Netherlands, to supply Charles Taylor's army in exchange for lumber.[86] In Zimbabwe, Mugabe bought $240m of weapons, while Sudan received civil helicopters and planes which were later militarized on site.[20]

Further, Chinese arms are basically low cost items, sold in large quantities for relatively low costs: machetes, low-priced assault rifles like the Type 56, or the QLZ87 grenade launcher.[20] These items have a far lower value than a single jetfighter or attack helicopter sold by the US but can kill far more people. That is what happened during the 1994 Rwanda genocide, with large quantities of "Made in China" machetes. Those "light weapons", when supplied in large quantities, become a tool of mass destruction.[20]

Natural resources

China's energy policy

| Region | Country | Share % |

|---|---|---|

| Middle East | Saudi Arabia | 15.6 |

| Middle East | Iran | 15 |

| Middle East | Oman | 11.3 |

| Africa | Angola | 9 |

| Africa | Sudan | 7.7 |

| Middle East | Yemen | 5.2 |

| Asia | Russia | 4.5 |

| Asia | Indonesia | 4 |

| Asia | Malaysia | 2.3 |

| Africa | Equatorial Guinea | 2.2 |

| Africa | Congo | 1.5 |

| Africa | Gabon | 1.2 |

| Africa | Cameroon | 1.1 |

| Africa | Algeria | 0.75 |

| Africa | Nigeria | 0.6 |

| Africa | Egypt | 0.3 |

| Miscellaneous | Others | 17.75 |

| 1990 | 2000 | 2004 |

|---|---|---|

| Mdl East | ||

| 39.4 | ↑53.5 | ↓45.4 |

| Africa | ||

| 0 | ↑23 | ↑28.7 |

| Asia pacific | ||

| 60.6 | ↓↓15.1 | ↓11.5 |

| other | ||

| 0 | ↑7.2 | ↑14.3 |

As a result of Soviet technology-sharing through the mid-1960s and internal reserves such the Daqing oil field, the PRC became oil sufficient in 1963.[90] Chinese ideology and the US-led embargo, however, isolated the Chinese oil industry from 1950 to 1970 preventing their evolution into powerful multinational companies.[90] Chinese oil exports peaked in 1985, but rapid economic reforms and an internal increase in oil demand brought China into an oil deficit, becoming a net oil importer in 1993, and a net crude importer in 1996,[90] a trend which is accelerating.[91] Indeed, Chinese reserves, such as the Tarim Basin, have proven both difficult to extract and difficult to transport toward Chinese coastal provinces where energy demand is centered. Pipeline construction, as well as processing facilities, lag behind demand.[92]

Through the end of the 20th century, China has been working to establish long-term energy security. Achieving this goal has required investment in oil and gas fields abroad, diversifying energy resource providers, and incorporating non-traditional energy sources like nuclear, solar and other renewables.[88] Although as of 2023 China is less reliant on African oil, energy security remains an important priority in China's relationships with African countries.[54]: 335

The rapid expansion of overseas activities by China's energy companies has been driven by the needs of both government and the PRC's National Oil Companies (NOC), which have worked in an uncommonly close partnership to increase overseas production of oil and gas.[93] Together, they gained access to projects of strategic importance in African nations like Sudan and Nigeria in the 1990s, while leaving smaller opportunities to the companies alone.[93]

Chinese actions in these areas have not always been successful: The 2006 agreement in Rwanda proved unproductive, while Guinean oil technologies were not familiar to Chinese companies.[94] The expansion has also been limited: all together, Chinese oil companies produced 257,000 bd in Africa in 2005—just one third of the leader ExxonMobil alone—and just 2% of Africa's total oil reserves.[94]

Moreover, China's arrival on the world oil scene has been perturbing for established players. China has been attacked for its increasingly close relationship with rogue states, such as Sudan and Angola, countries known for their human rights abuses, political censorship, and widespread corruption.[95] China's world image has suffered from the critiques, leading the nation to move to a more diplomatic approach, avoiding crisis areas, such the Niger Delta.[94] Nevertheless, as a consumer country and budding powerhouse,[96] China has little choice in choosing its source of supply.[97]

Chinese access to international oil markets has satisfied the country's immediate thirst. But despite its large coal-based energy system, China is a key part of the vicious cycle which had led to increasing oil prices worldwide—to the disadvantage of all industrialized and oil importing countries, including China itself.[98] In 2006, China imported 47% of its total oil consumption (145 Mt of crude oil).[99][100]

With such high demand, Chinese companies such as Sinopec, China National Petroleum Company (CNPC), and China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC), have looked to Africa for oil. China National Petroleum Corporation was the first Chinese enterprise to invest in Africa.[54]: 165 In 1996, it began developing oil fields previously discovered by Chevron in Sudan, but which Chevron had abandoned due to civil conflict in Sudan.[54]: 165 After South Sudan's independence in 2011, South Sudan's territory included many of the Sudanese oil fields where CNPC and Sinopec have significant interests.[54]: 165

African natural resource exports

| Resource | Global share |

| Bauxite | 9% |

| Aluminum | 5% |

| Chromite | 44% |

| Cobalt | 57% |

| Copper | 5% |

| Gold | 21% |

| Iron ore | 4% |

| Steel | 2% |

| Lead | 3% |

| Manganese ore | 39% |

| Zinc | 2% |

| Cement | 4% |

| Diamond | 46% |

| Graphite | 2% |

| Phosphate rock | 31% |

| Coal & Petroleum | 13% |

| Uranium | 16% |

|

Africa is the 2nd largest continent in the world, with 30 million square kilometers of land, and contains a vast quantity of natural resources. This trait, together with the continent's relatively low population density and small manufacturing sector has made Africa a key target for Chinese imports.

Africa ranks first or second in abundance globally for the following minerals: bauxite, cobalt, diamonds, phosphate rocks, platinum group metals, vermiculite, and zirconium.[107] Many other minerals are also present in high quantities.

Many African countries are highly dependent on such exports. Mineral fuels (coal, petroleum) account for more than 90% of the export earnings for: Algeria, Equatorial Guinea, Libya, and Nigeria.[105] Various Minerals account for 80% for Botswana (led by, in order of value, diamond, copper, nickel, soda ash, and gold), Congo (petroleum), Congo (diamond, petroleum, cobalt, and copper), Gabon (petroleum and manganese), Guinea (bauxite, alumina, gold, and diamond), Sierra Leone (diamond), and Sudan (petroleum and gold). Minerals and mineral fuels accounted for more than 50% of the export earnings of Mali (gold), Mauritania (iron ore), Mozambique (aluminum), Namibia (diamond, uranium, gold, and zinc), and Zambia (copper and cobalt).[105]

Ongoing mining projects of more than $1 billion are taking place in South Africa (platinum, gold), Guinea (bauxite, aluminum), Madagascar (nickel), Mozambique (coal), Congo and Zambia (cobalt, copper), Nigeria and Sudan (crude petroleum), and Senegal (iron)

Historical oil export and production data

Africa produced about 10.7 Mbpd of oil in 2005, 12% of the 84 Mbpd produced worldwide.[108] Around one half of that is produced in north Africa, which has preferential trade agreements with Europe.[105] The sub-Saharan oil producers include by global rank and Mbpd: Nigeria (13th; 2.35Mbpd), Angola (16th; 1.91Mbpd), Sudan (31st; .47Mbpd). Guinea (33rd), Congo (38th), and Chad (45th) also have notable oil output.[108]

In 2005, 35% of exported African oil went to the EU, 32% to the US, 10% to China, while 1% of African gas goes to other parts of Asia.[105] North African preferentially exporting its oil to western countries: EU 64%; US 18%; all others 18%.[105] 60% of African wood goes to China, where it is manufactured, and then sell across the world.[45]

As of 2007, thanks to good diplomatic relations and recent growth, Africa provides 30% of China's oil needs,[109] with Sudanese's oil account for 10 of these 30 points.[110]

Major projects

Chinese companies have recently increased their activity worldwide. Some major projects include:

- Sudan. In 1997 CNPC's Great Wall Drilling Company agreed to buy a 40% stake in the $1.7 "Greater Nile Petroleom Operating Company", contract renewed and expanded in 2000;[88][111] CNPC owns most of a field in south Darfour and 41% of a field in Melut Basin, expected to produce 300,000 bpd in 2006; Sinopec is erecting a pipeline, building a tanker terminal in Port-Sudan.[111] 60% of Sudan's oil output goes to China;[94] since the 1990s, China has invested $15b, mainly in oil infrastructure.[110]

- Nigeria. In 1998 CNPC bought two oil blocks in the Niger delta;[88] in 2005, four blocks, together with other companies, in exchange for a hydropower plant in Mambila with 1,000 MW capacity and a taking controlling stake in 1,100,000 bpd from the Kaduna refinery;[111] CNOOC has paid $2.7b for a rich oil block.[94]

- Angola. Proposal for a $5 billion loan for oil-related and structural infrastructcure for post-war rebuilding, to be repaid in oil;[64][88] Sinopec owns 50% of Angola BP-operated Greater plutonio project.[94]

- Gabon. In 2004 Feb, China signed a technical evaluation agreement with the Gabonese oil ministry for 3 onshore fields.[111]

Similar or greater projects are taking place in Middle East and Latin America, one Sino-Iranian deal having an estimate value of US$70 billion.

Information technology

Chinese companies have successfully entered Africa's information technology, both with and without Chinese state support.[54]: 310

China seeks to support expansion of its information technology industry to Africa through a financial assistance program for African countries.[54]: 310 Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe receive 50% of China's aid for information technology to Africa.[54]: 310 Aid for information technology accounts for only a relatively small amount of China's aid to Africa, however.[54]: 310

Huawei and ZTE are the Chinese companies that primarily implement information technology solutions paid for via Chinese information technology aid to Africa.[54]: 310

Macroeconomic and political strategy

China, once in need of international recognition and now in need of raw materials, has walked carefully and humbly towards Africa. The dynamic evolved into what is now called the "Beijing Consensus", China's "soft" diplomatic policy, entailing a strict respect for African sovereignty and a hands-off approach to internal issues.[112] In short: loans and infrastructure without any political strings about democracy, transparency, or human rights attached.[31]

China's 'non-interference' model gives African leaders more freedom and the opportunity to work for immediate economic development. With China, controversial African leaders face a second or third chance to join in international partnerships this time with a successful third world nation; many of the excuses about Western domination which had previously been used to justify Africa's lack of growth can no longer be made.

To the West, China's approach threatens the promotion of democracy, transparency, liberalism and free trade, engaging instead with authoritarianism, economic development at the expense of civil progress, and strengthened ties between political and economic elites over of broad social change. To China, who regards the West's 'human rights discourse' as blatantly hypocritical, their involvement with so-called rogue states increases long term stability and much needed "win-win" social and economic development.

The arrival of a new actor in Africa has led Westerners to review their own strategies as they analyze Chinese actions in Africa. The Western responses may ultimately aid Africa, as think tanks provide strategic analysis on how African elites can get more out of Chinese investments.[113]

Indeed, it's clearly in the interest of Africa to play one side against the other, and to avoid alliances between China and the West, which might work to decrease raw material prices.[114] Legal power remains in the hands of local African elites, who may or may not decide to enforce laws which would tighten control of resources, or further exploit them. Pursuing democracy and transparency is no longer the sole model;[22] development is, for sure, and as long as African leaders can provide it, their power will be that much assured.

Competition with Taiwan

The Republic of China (ROC), commonly known as Taiwan, is a fierce diplomatic rival of the People's Republic of China. Following the Chinese Civil War, both claimed to be the legitimate representative of 'China' on the world scene. At that time, the USSR supported the PRC, while the United States backed ROC, which thus held the Chinese UN security council's seat along with its high visibility and veto power. In 1971, after a complex struggle, the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s led the United States to offer the UN security council seat to the PRC, thus excluding ROC-Taiwan from the diplomatic scene.

Many countries followed the US move. Yet Taiwan's strengthening economy in the 1970s and 1980s allowed the country to keep some strongholds across the world, which supported ROC's diplomatic claim to the UN. As the PRC grew in power, Taiwan was only able to keep smaller supporters, mainly in the Pacific islands, Latin America, and Africa.

In the 1990s, the political power-play between Taiwan and China often spurred investment in Africa, with a number of large-scale projects seeking to garner influence and recognition.[47]

African countries recognizing the ROC

|

|

Nowadays, the balance of power in terms of African friendship seems to be in favour of the PRC. Taiwanese investments in Africa are about $500 million a year, while Chinese Eximbank alone is approaching $20 billion over 3 years.[115]

Several Senegalese projects were funded by Taiwan in May 2005, as part of a 5-year plan including $120 million. But soon after the bank transfer was completed, Senegal moved to support the PRC, and a "development based on free market and fair bids".[47] Abdoulaye Wade, the president of Senegal also wrote to the ROC's president, saying, "Between countries, there is not friendship, just interests."[116]

The last oil producer allied to Taiwan was Chad. But in April 2006, a PRC-Sudan backed coup d'état attempt came close to overthrowing the pro-Taiwanese leader, Idriss Deby. The effort was eventually stopped by French military intervention. Deby first looked for Taiwanese loans to enhance its military strength. Taiwan was unable to provide the $2 billion which had been requested, and Deby switched to recognising the PRC, thus weakening the coup and strengthening himself.[117] Today, four countries in Africa recognize ROC-Taiwan.

African integration

Efforts have been made toward stronger economic integration in Africa. In 2002, the African Union was formally launched to accelerate socio-economic integration and promote peace, security, and stability on the continent.[52] The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) was also created by pro-democracy African states, headed by South Africa. Ian Taylor, an expert of Sino-African relations, wrote, "NEPAD has succeeded in placing the question of Africa's development on the international table and claims to be a political and economic program aimed at promoting democracy, stability, good governance, human rights and economic development on the continent. Despite its faults, NEPAD is at least Africa-owned and has a certain degree of buy-in."

Taylor concludes: "China's oil diplomacy threatens to reintroduce practices [such as corruption, human rights abuses] that NEPAD (and the African Union for that matter) are ostensibly seeking to move away from—even though China protests that it fully supports NEPAD"[118] A Chinese-lead Forum on China-Africa Cooperation has been created, where Chinese and African partners meet every 3 years, both to strengthen alliances, sign contracts, and to make important announcements. The forum also helps African leaders to gain legitimacy in their own countries.

China and the resource shortage hypothesis

Key reasons of China's interest on Africa are to be found in China itself. Chinese economy, industry, energy and society have a special shape. Chinese economy and industry turn toward export markets.[119] These industries and associated works and investment provide the Chinese society the recent two-digit yearly economic growth, job chances, and life standard improvement, but dramatically rely on coal (70%) and oil (25%) sources (for 2003),[120] as well as raw materials. Notable are the frequent electric shortages. A US Congress hearing noticed that energy shortages have already led to rationing of the electric supply, slowing down manufacturing sector and consequently overall economic growth.[121] On other raw materials side, China simply does not have enough natural resources of its own to meet its growing industrial need.[122]

Within the China economic success story, western scholars noticed that China's quest of wealth has once more led coastal provinces to quickly enrich, while inland provinces or rural areas stay relatively poor, an inequality which thus leads to internal social tensions and instability.[123] Recent economic growth helped to stabilize the Chinese society: in times of economic growth, individuals look simply for personal life improvement. Millions of poor farmers and workers work hard and silently in hope of a better lives tomorrow; they want to buy TVs, computers, cellphones, cars, fridges. To keep them happy and stable, China has to stay largely supplied in raw materials – oil, copper, zinc, cobalt – from abroad.[122] Also, driven by this politico-economic desire to obtain sources of raw materials and energy for China's continuing economic growth and open up new export markets, China is actively looking for African resources of every kind: oil, cobalt, copper, bauxite, uranium, aluminium, manganese, iron ore etc.[122][124] African resources feed Chinese industries' hunger for minerals and electricity, fuel its economic boom, and thus keep the country's consumers happy and quiet.[122]

For the CCP, enough supply of minerals means social stability. Like other power, China needs to supply its industry with raw materials, and its citizen in goods to keep them happy.[122] Out of energy and raw materials shortage, analysts also notice that long-term factors threatening China's growth questions over its innovation capability, corruption and inefficiency, and environmental risks.

Criticism

Fears of colonialism

Chinese companies allegedly do not treat and pay the African workers well.[125] There are also allegations of African local workers losing their jobs to workers who are coming from China.[125] The cheaper Chinese products are pushing the local products out of the market.[125]

According to the 2nd session of the 2011 China Africa Industrial Forum hosted in Beijing, China-Africa trade volume was expected to exceed 150 billion US dollars by year 2011.[126] As with previous Western involvement in Africa, forging close ties with local elites has been a key strategy for Chinese diplomats and businessmen.[127] It has been noted that when new leaders come to power in Africa, they will "quickly launch a maximum of new projects [with state's money] to get personal commissions immediately, all this is decided in a short time, and we are ready".[128]

In Angola, a country weakened by years of conflict, and now notable for its institutional corruption,[129] China has proposed low-cost loans (1.5%), to be paid back in oil.[130] For the elite of Angola, unlike other investors, China does not insist on transparent accounting or the assurance good governance.[131] The long-term consequences for African democracy may be serious. As noted in a South African newspaper, "China's no-strings-attached buy-in to major oil producers, such as Angola, will undermine efforts by Western governments to pressure them to open their oil books to public scrutiny."[130]

Human rights

Cases of human rights abuses have arisen from Chinese-African co-operation. African workers have protested against ill-treatment and poor pay by Chinese companies, as well as the influx of Chinese workers who take away local jobs. In July 2010, hundreds of African workers at a Chinese-owned Zambian mine rioted over low wages.[132]

In the Republic of Congo, Chinese contracts are said to be 30% cheaper than Western ones. African workers, however complain of worsening conditions: Chinese firms hire them on a day-to-day basis, with lower wages than they received from Westerner firms, are insulting or even racist, and enforce strict working conditions.[45] African businessmen have long complained of an increase in Chinese businesses, especially in Senegal.[citation needed] Some Angolans had complained that along with the shipment of machinery and cement, China also imports many of its own nationals to work on these reconstruction projects, leaving little employment for locals, and not allowing for cooperative working relations or the transfer of knowledge and skills.[133]

In the factories of Congo, the Chinese work 12 hours a day, six days a week, maintaining machinery on Sundays.[45] Such high activity is also expected from African workers, sometimes creating tensions between groups.

There are typically two kinds of Chinese organizations operating in Africa: firms transforming African resources in which the bosses, managers, and technicians are Chinese, the workers are African, and the customers are Europeans, Americans, and Japanese; and firms selling to African markets in which the bosses and managers are Chinese, the sellers are Chinese, and the customers are African.

Both types create social tensions, economic conflict with local enterprises, lower short-term employment prospects for Africans, and an apparent ethnic hierarchy within the firms.[134][135] In Angola, like elsewhere in Africa, Chinese workers live separately from native Africans, especially in large-scale work led by Chinese enterprises, where 'Chinese camps' are specially built, exaggerating linguistic and cultural difficulties between workers.[136]

Disruption of African manufacturing

One contentious issue is the effect which large amounts of Chinese goods are having on local light manufacturing. While the dominant resource extraction industries are largely benefiting from Chinese capital investment, growing imports from China to many African nations underprice and crowd out local suppliers.[31] Though Chinese imports allow poorer consumers to buy their first refrigerator, T-shirt, suitcases, or microwave ovens, they also hurt nascent local industries in countries trying to end reliance on resource commodities. By one interpretation, Chinese textile imports have caused 80% of Nigerian factories to shut down, resulting in 250,000 workers losing their jobs.[25]

In Zambia, trade minister M. Patel complains: "we [Zambian industries] are simply not competitive in the way we produce goods". In a post Cold War, WTO-oriented Africa, consumer goods manufacturers never recovered from the first wave of Chinese products.[25] Basic African factories cannot compete with the Chinese in terms of productivity or quality.[25]

"Resource curse" hypothesis

In recent decades researchers have considered a link between the natural resource abundance of a country and adverse consequences for economic growth and government functioning. This trend seems especially common for countries with 'point source' minerals such as mines and oil fields, which create large profits for few people. Compared to agricultural resources, which offer diffuse development requiring large quantities of workers and distributing the benefits more widely, point source minerals have the potential to stifle the socioeconomic development of a nation.[32]

Evidence has been provided by Sachs & Warner, 2001 that establishes:

...an inverse statistical relationship between natural resource based exports (agriculture, minerals and fuels) and growth rates during the period 1970–1990. Almost without exception, the resource-abundant countries have stagnated in economic growth since the early 1970s, inspiring the term ‘curse of natural resources’. Empirical studies have shown that this curse is a reasonably solid fact.[32]

Taylor notes that China's blind support of the African elite in a resource-abundant country may worsen the 'resource curses', by encouraging elites to tighten their control resources and damage other economic sectors. Such arrangements may be in the short-term interest of Beijing, who often want to keep importing low cost raw materials from abroad, and manufacture them in China.[48]

The notion of a "curse" may be misleading, as countries do have choice, and the development of natural resources sector is shaped by a host of government policies. Wright & Czelusta note 6 relevant policy issues:

- infrastructure of public knowledge (e.g., geological surveys);

- engineering education;

- systems of exploration concessions and property rights for mineral resources;

- export and import controls;

- supporting infrastructure (such as transportation);

- targeted taxes or royalties.[137]

Chinese investments focus on infrastructure, the 5th point. The remaining five, however, are largely in the hands of African elites.

African fishermen complain of Chinese industrialised fishing, coming as close as one nautical miles off the coast, depleting fish stocks, and interfering with villagers' fishing nets for whom fishing is the main income source.[45] Western pro-Forest NGO complains of Chinese specific disdain for environment.[45]

Regulatory response

Given current global growth, African leaders are looking to first build up infrastructure, but are also increasingly aware of the need to strengthen native industries and economies. Following their experience with western involvement and the current world dynamic of growing demand for raw materials, African states are attempting to mitigate a possible repeat of exploitation under the Chinese with efforts to encourage local, long-term development.

Examples are:

| Country | Comment |

|---|---|

| Nigeria | Some protectionist laws came into force in 2003 concerning foreign low-cost goods. These laws are being encouraged by some of the Chinese migrant population who also hope to develop local industry.[138] |

| Senegal | Leaders have negotiated an open-door policy from the PRC, which has brought thousands of visas to Senegalese businessmen working in Western China and importing Chinese goods to Senegal.[139] A Chinese company cannot be awarded an infrastructure contract unless it is partnered with a local company, encouraging the transfer of technology and knowledge to African workers.[47] |

| Republic of Congo | Law now requires that 85% of trees from local forests are processed inside the country, even if this is made more difficult because of the space and quantity involved.[45] This idea is also encouraged in other countries[140] |

| Zambia | Chinese demand for copper from Zambia is being met with proposals to require Chinese firms to process the copper in Zambia, rather than elsewhere.[140] |

See also

- Sino-African relations

- Forum on China-Africa Cooperation

- Foreign relations of PRC

- Foreign relations of ROC

- Economy of China

- Economy of Africa

- Mineral industry of Africa

- Debt-trap diplomacy

- AU Conference Center and Office Complex

References

- ^ a b Zongwe, Dunia (2010). "On the Road to Post Conflict Reconstruction by Contract: The Angola Model". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1730442. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 150819659.

- ^ Abegunrin, Olayiwola; Manyeruke, Charity (2020). China's power in Africa: a new global order. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 27. ISBN 978-3-030-21993-2.

- ^ "China Africa Trade: Chinese have Replaced Britishers as our Masters!". 21 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h LCA, pp. 105–109

- ^ "The Archaeological Researches into Zheng He's Treasure Ships". Archived from the original on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ Yuan Wu (2006). La Chine et l'Afrique, 1956–2006. China Intercontinental Press.

- ^ a b LCA, pp. 87–88

- ^ LCA, p. 54

- ^ http://www.statssa.gov.za/PublicationsHTML/P03022007/html/P03022007.html[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b LCA, p. 67

- ^ a b c LCA, pp. 109–110

- ^ a b LCA, pp. 40–42

- ^ CIA, p. 135

- ^ a b c d e f g LCA, pp. 111–112

- ^ Waving Goodbye to Hegemony, Parag Khanna Archived 16 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ LCA, p. 350 (map)

- ^ Bristow, Michael (29 November 2007). "China's long march to Africa". BBC News.

- ^ LCA, p. 100

- ^ Rotberg, Robert (2009). China into Africa: Trade, Aid, and Influence. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 156–159. ISBN 9780815701750.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i LCA, pp. 221–235 – arms

- ^ a b c d e CPA

- ^ a b c d e f g CRW

- ^ Privilege Musvanhiri, Hang Shuen Lee (9 December 2015). "Economic interests push China to increase military presence in Africa". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Lydia Polgreen (26 March 2009). "As Chinese Investment in Africa Drops, Hope Sinks". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d FTT, p4.2: Pros and Cons.

- ^ a b LCA, pp. 305–06

- ^ "Cheikh Faye, what's next for Africa ?". Afrikonomics.com. 12 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ a b International Monetary Fund, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=2008&ey=2011&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=924&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CLP&grp=0&a=&pr.x=39&pr.y=6

- ^ Zafar, Ali (2007). "he Growing Relationship Between China and Sub-Saharan Africa: Macroeconomic, Trade, Investment, and Aid Links" (PDF). The World Bank Research Observer. 22 (1): 103–130. doi:10.1093/wbro/lkm001.

- ^ ""World Population Prospects, the 2010 Revision". Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012." United Nations (Department of Economic and Social Affairs, population division)

- ^ a b c CB5, Thompson, pp. 1–4

- ^ a b c MRE, pp. 0–3

- ^ LCA, p. 59

- ^ a b "China emerging as a major destination for African students". ICEF Monitor - Market intelligence for international student recruitment. 21 April 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Recruiting in Africa: US faces a stiff competitor in China". University World News. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Coelho, Rute (24 June 2020). "China wins the West in offering scholarships to African students". Plataforma Media. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ CEC, pp. 15–17; LCA, p. 29

- ^ CEC, p15: China World trade 1979–2007.

- ^ LCA, p. 29

- ^ CEC, p. 16

- ^ CEC, p. 17

- ^ a b c Murphy, Dawn C. (2022). China's rise in the Global South: the Middle East, Africa, and Beijing's alternative world order. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-5036-3060-4. OCLC 1249712936.

- ^ CEC, pp. 9–14 (+ personal calculs for percentages)

- ^ Kingsley Ighobor (January 2013). "China in the heart of Africa". Un.org. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h LCAtv

- ^ FTT, p. 2

- ^ a b c d e FTT, p. 6, Senegal's president Abdoulaye Wade's article.

- ^ a b COD, pp. 951–952

- ^ APG, p. 9

- ^ Dankwah, Kwaku Opoku and Marko Valenta (2019) (2019). "Chinese entrepreneurial migrants in Ghana: socioeconomic impacts and Ghanaian trader attitudes". Journal of Modern African Studies. 57: 1–29. doi:10.1017/S0022278X18000678.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Sam Piranty (5 December 2015). "Seven surprising numbers from China-Africa trade". Bbc.com. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ a b MIA, introduction

- ^ a b c "China and Africa trade". Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Shinn, David H.; Eisenman, Joshua (2023). China's Relations with Africa: a New Era of Strategic Engagement. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-21001-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Murphy, Dawn C. (2022). China's rise in the Global South: The Middle East, Africa, and Beijing's alternative world order. Stanford, California. ISBN 978-1-5036-3060-4. OCLC 1249712936.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e Murphy, Dawn C. (2022). China's rise in the Global South: the Middle East, Africa, and Beijing's alternative world order. Stanford, California. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-5036-3060-4. OCLC 1249712936.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Murphy, Dawn C. (2022). China's rise in the Global South: the Middle East, Africa, and Beijing's alternative world order. Stanford, California. pp. 182–188. ISBN 978-1-5036-3060-4. OCLC 1249712936.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f Brautigam, Deborah; Tang, Xiaoyang (6 January 2010). "China's Investment in African Industrial Zones" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ "NFCM plan to invest in Chambishi South mine in Zambia". Steel Guru. 7 July 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ Xinhua (16 January 2009). "Zambia-China Economic Zone launches sub-unit in Lusaka". China Daily. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ Xinhua (16 September 2009). "Mauritius Jinfei Economic Trade and Cooperation Zone Project kicks off". Government of Mauritius. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ Xu Weiyi (12 October 2010). "Suez Economic Zone Deepens China-Africa Cooperation". CRI English. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d FTT, p. 3.1

- ^ a b APG, p1

- ^ a b APG, p. 10

- ^ a b c d "China EximBank (introduction)". Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ "China banks lend more than World Bank – report". BBC News. 18 January 2011.

- ^ LCA, pp. 64–66

- ^ LCA, p. 316

- ^ APG, p. 4

- ^ LCA, pp. 23–24

- ^ LCA, p. 32

- ^ LCA, p. 110

- ^ LCA, p. 325

- ^ "The Report: Algeria 2010 page 165". Oxford Publishing Group. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Chinese Funded Railways". CNN. 22 November 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "Government Signs Commercial Contract for the Nairobi to Malaba SGR Section with CCCC". Kenya Railways. Retrieved 18 January 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Mali signs $11bn agreements with China for new rail projects". Railway Technology. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "China to build major new African railway from Mali to the coast". Global Construction Review. 4 January 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "CCECC sign $11.117 billion Lagos-Calabar Rail Contract line". The Guardian. 2 July 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "Abuja-Kaduna Rail line". Railway Technology. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "Construction of railway from Khartoum to Port Sudan". Aiddata. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ David Lumu, and Samuel Balagadde (30 August 2014). "Chinese Firm CHEC Given US$8 Billion Railway Deal". New Vision (Kampala). Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ Jin, Haixing (31 March 2015). "China's Xi Finds Eight Good Reasons to Host Uganda's President". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ Monitor Reporter (30 March 2015). "Museveni Signs Deal With Chinese Company To Construct Kasese Railway Line". Daily Monitor. Kampala. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ Dead on Time – arms transportation, brokering and the threat to human rights (PDF). Amnesty international. 2006. pp. 22–28.

- ^ China Perspective, 2005. Data from: United Nations Statistics division Archived 18 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e CQE, pp. 12–15

- ^ CES, p. 49

- ^ a b c CES, pp. 39–40

- ^ CES, p. 41

- ^ IEA, pp. 71–73

- ^ a b Xin, Philip Andrews-Speed (1 March 2006). "The Overseas Activities of China's National Oil Companies: Rationale and Outlook (abstract)". Minerals & Energy – Raw Materials Report. 21: 17–30. doi:10.1080/14041040500504343.

- ^ a b c d e f FTT, p6.1: Beijing learns to tread warily.

- ^ CES, pp. 47–49

- ^ CES, p. 48

- ^ CES, p. 53

- ^ CES, p44-45 – China making 40% of the 2004 oil consummation increase

- ^ "China's oil imports set new record". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011.

- ^ "China's 2006 crude oil imports 145 mln tons, up 14.5 pct - customs - Forbes.com". Forbes. 19 November 2007. Archived from the original on 19 November 2007.

- ^ a b MIA p. 1.6

- ^ a b MIA p. 1.4