Pine Gap

| Pine Gap Australia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 23°48′00″S 133°44′15″E / 23.80000°S 133.73750°E |

| Part of a series on |

| Global surveillance |

|---|

| Disclosures |

| Systems |

| Selected agencies |

| Places |

| Laws |

| Proposed changes |

| Concepts |

| Related topics |

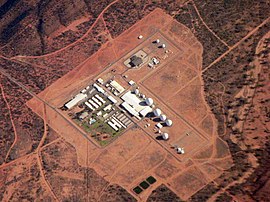

Pine Gap is a satellite surveillance base and Australian Earth station approximately 18 km (11 mi) south-west of the town of Alice Springs, Northern Territory in the center of Australia. It is jointly operated by Australia and the United States, and since 1988 it has been officially called the Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap (JDFPG); previously, it was known as Joint Defence Space Research Facility.[1]

The station is partly run by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), US National Security Agency (NSA), and US National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) and is a key contributor to the NSA's global interception/surveillance effort, which included the ECHELON program.[2][3][4][5] The classified NRO name for the Pine Gap base is Australian Mission Ground Station (AMGS), while the unclassified cover term for the NSA function of the facility is RAINFALL.[6]

The base

The facilities at the base consist of a massive computer complex with 38 radomes protecting radio dishes[7] and operates with over 800 employees.[8] NSA employee David Rosenberg indicated that the chief of the facility was a senior CIA officer at the time of his service there.[9]: p 45–46 [10]

The location is strategically significant because it controls United States spy satellites as they pass over one-third of the globe, including China, the Asian parts of Russia, and the Middle East.[7] Central Australia was chosen because it was too remote for spy ships passing in international waters to intercept its signals.[9]: p xxi The facility has become a key part of the local economy.[11]

Operational history

In late 1966, during the Cold War, a joint US–Australian treaty called for the creation of a US satellite surveillance base in Australia, to be titled the "Joint Defence Space Research Facility".[12] The purpose of the facility was initially referred to in public as "space research".[13] Operations started in 1970 when about 400 American families moved to Central Australia.[11]

Since the end of the Cold War in 1991 and the rise of the war on terror in 2001, the base has seen a refocusing from mere nuclear treaty monitoring and missile launch detection, to become a vital warfighting base for US military forces.[6] In 1999, with the Australian Government refusing to give details to an Australian Senate committee about the relevant treaties, intelligence expert Professor Des Ball from the Australian National University was called to give an outline of Pine Gap. According to Ball, since 9 December 1966 when the Australian and United States governments signed the Pine Gap treaty, Pine Gap had grown from the original two antennas to about 18 in 1999, and 38 by 2017.[14] The number of staff had increased from around 400 in the early 1980s to 600 in the early 1990s and then to 800 in 2017, the biggest expansion since the end of the Cold War.[citation needed]

Ball described the facility as the ground control and processing station for geosynchronous satellites engaged in signals intelligence collection, outlining four categories of signals collected:

- telemetry from advanced weapons development, such as ballistic missiles, used for arms control verification;

- signals from anti-missile and anti-aircraft radars;

- transmissions intended for communications satellites; and

- microwave emissions, such as long-distance telephone calls.

Ball described the operational area as containing three sections: Satellite Station Keeping Section, Signals Processing Station and the Signals Analysis Section, from which Australians were barred until 1980. Australians are now officially barred only from the National Cryptographic Room (similarly, Americans are barred from the Australian Cryptographic Room). Each morning the Joint Reconnaissance Schedule Committee meets to determine what the satellites will monitor over the next 24 hours.

With the closing of the Nurrungar base in 1999, an area in Pine Gap was set aside for the United States Air Force's control station for Defense Support Program satellites that monitor heat emissions from missiles, giving first warning of ballistic missile launches. In 2004, the base began operating a new satellite system known as the Space-Based Infrared System, which is a vital element of US missile defense.[7]

Since the end of the Cold War, the station has mainly been employed to intercept and record weapons and communications signals from countries in Asia, such as China and North Korea. The station was active in supporting the wars in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan and Iraq and every US war since the September 11 attacks.[15][16]

The Menwith Hill Station (MHS) in the UK is operated by the NSA and also serves as ground station for these satellite missions.[6]

One of Pine Gap's primary functions is to locate radio signals in the Eastern Hemisphere, with the collected information fed into the US drone program.[17][18] This was confirmed by an NSA document from 2013, which says that Pine Gap plays a key role in providing geolocation data for intelligence purposes, as well as for military operations, including air strikes.[6]

On 11 July 2013, documents revealed through former NSA analyst Edward Snowden showed that Pine Gap, amongst three other locations in Australia and one in New Zealand, contributed to the NSA's global interception and collection of internet and telephone communications, which involves systems like XKEYSCORE.[6] Journalist Brian Toohey states that Pine Gap intercepts electronic communications from Australian citizens including phone calls, emails and faxes as a consequence of the technology it uses.[19]

According to documents published in August 2017, Pine Gap is used as a ground station for spy satellites on two secret missions:[6]

- Mission 7600 with 2 geosynchronous satellites to cover Eurasia and Africa

- Mission 8300 with 4 geosynchronous satellites that covered the former Soviet Union, China, South Asia, East Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and countries on the Atlantic Ocean

Whitlam dismissal

Gough Whitlam, Prime Minister of Australia (between 1972 and 1975), considered closing the base.[20][21] Victor Marchetti, a CIA officer who had helped run the facility, said that this consideration "caused apoplexy in the White House, [and] a kind of Chile [coup] was set in motion", with the CIA and MI6 working together to get rid of the Prime Minister.[20][21] On 11 November 1975, the day Whitlam was scheduled to brief the Australian Parliament on the secret CIA presence in Australia, as well as it being "the last day of action if an election of any kind was to be held before Christmas", he was dismissed from office by Governor-General John Kerr using reserve powers, described as "archaic" by critics of the decision.[20][21]

In 2020, previously confidential private correspondences between the Palace and the Governor-General were released. In one of the letters, John Kerr describes his alleged CIA connections as "Nonsense of course", and assured the Queen of his continued loyalty.[22]

Protests

- On 11 November 1983, Aboriginal women led 700 women to the Pine Gap gates where they fell silent for 11 minutes to commemorate Remembrance Day and the Greenham Common protest in Britain. This was the beginning of a two-week, women-only peace camp, organised under the auspices of "Women For Survival". The gathering was non-violent but several women trespassed onto the military base. 111[23] women were arrested on one particular day and gave their names as Karen Silkwood, an American nuclear worker who died after campaigning for nuclear safety. There were allegations of police brutality and a Human Rights Commission inquiry ensued.[24]

- On 5–7 October 2002, a number of groups (including Quakers and the National Union of Students) gathered at the gates of Pine Gap to protest the use of the base in the then-impending Iraq war.[25]

- In December 2005, six members of the Christians Against All Terrorism group staged a protest outside Pine Gap. Four of them later broke into the facility and were arrested. Their trial began on 3 October 2006 and was the first time that Australia's Defense (Special Undertakings) Act 1952 was used.[26] The Pine Gap Four cross-appealed to have their convictions quashed. In February 2008, the four members successfully appealed their convictions and were acquitted.[27]

In popular culture

Peter "Turbo" Teatoff is seen delivering heavy machinery to JDFPG in season 4's 11th episode of series Outback Truckers.

Pine Gap features prominently in the third and fourth thriller novels of the Jack West Jr. series—The Five Greatest Warriors and The Four Legendary Kingdoms, respectively—by the Australian writer Matthew Reilly.

Pine Gap is featured in the 2018 Australian television series of the same name. The series is a political thriller, portraying the lives of the members of the joint American–Australian intelligence team.

In The Secret History of Twin Peaks by Mark Frost, President Richard Nixon claims that Pine Gap is actually the site of an underground facility constructed by extraterrestrials.

In 1982 the Australian band Midnight Oil released "Power and the Passion", which contains a reference to Pine Gap.

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Hamlin, Karen (2007). "Pine Gap celebrates 40 years". Defence Magazine. 2007/8 (3): 28–31. ISSN 1446-229X. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ Dorling, Philip (26 July 2013). "Australian outback station at forefront of US spying arsenal". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Loxley, Adam (2011). The Teleios Ring. Leicester: Matador. p. 296. ISBN 978-1848769205.

- ^ Robert Dover; Michael S. Goodman; Claudia Hillebrand, eds. (2013). Routledge Companion to Intelligence Studies. Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 9781134480296.

- ^ "Mission Ground Station Declassification (NRO)" (PDF). 15 October 2008. National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 June 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Peter Cronau, The Base: Pine Gap's Role in US Warfighting Archived 18 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Background Briefing, ABC Radio National, 20 August 2017; Ryan Gallagher and Peter Cronau, The U.S. Spy Hub in the Heart of Australia Archived 23 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine, The Intercept, August 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c Middleton, Hannah (2009). "The Campaign against US military bases in Australia". In Blanchard, Lynda-ann; Chan, Leah (eds.). Ending War, Building Peace. Sydney University Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-1920899431. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ [1] Archived 22 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 21 July 2013. Accessed 21 July 2013

- ^ a b Rosenberg, David (2011). Inside Pine Gap: The Spy who Came in from the Desert. Prahran, Victoria: Hardie Grant Books. ISBN 9781742701738.

- ^ Harris, Reg Legendary Territorians, Harris Nominees, Alice Springs, 2007, p 93, ISBN 9780646483719.

- ^ a b Stanton, Jenny (2000). The Australian Geographic Book of the Red Centre. Terrey Hills, New South Wales: Australian Geographic. p. 57. ISBN 1-86276-013-6.

- ^ "Treaties". www.info.dfat.gov.au. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Dent, Jackie (23 November 2017). "An American Spy Base Hidden in Australia's Outback". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Ball, Desmond (28 May 2015). "Expanded Communications Satellite Surveillance and Intelligence Activities utilising Multi-beam Antenna Systems" (PDF). The Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability: 29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Coopes, Amy, Agence France-Presse/Jiji Press, "US eyes Asia from secret Australian base[permanent dead link]", Yahoo! News, 19 September 2011

- ^ Japan Times, 19 September 2011, p. 1.

- ^ Dorling, Philip (21 July 2013). "Pine Gap drives US drone kills". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Oliver Laughland. "Pine Gap's role in US drone strikes should be investigated – rights groups". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Snow, Deborah (31 August 2019). "Tantalising secrets of Australia's intelligence world revealed". The Age. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Pilger, John (23 October 2014). "The British-American coup that ended Australian independence". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Zhou, Naaman (14 July 2020). "Gough Whitlam dismissal: What we know so far about the palace letters and Australian PM's sacking". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 September 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ "'Don't ever write and preach to me again': One missive in the Palace letters broke all the rules". www.abc.net.au. 18 July 2020. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Pine Gap Protests - historical http://nautilus.org/publications/books/australian-forces-abroad/defence-facilities/pine-gap/pine-gap-protests/protests-hist/ Archived 3 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine and Kelham, Megg Waltz in P-Flat: The Pine Gap Women's Peace Protest in Hecate 1 January 2010 available on-line at http://www.readperiodicals.com/201001/2224850971.html#b Archived 23 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Anti-Nuclear Campaign". uq.edu.au. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ "AABCC Pine Gap Protest Sept 2002 report". Australian Anti Bases Coalition. 2002. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007.

- ^ Donna Mulhearn & Jessica Morrison (6 October 2006). "Christian Pacifists Challenge Pine Gap In Court" (Press release). Scoop.co.nz. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- ^ "The Queen v Law & Ors [2008] NTCCA 4 (19 March 2008)". www.austlii.edu.au. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

Sources

- General sources

- 1999 Joint Standing Committee on Treaties. An Agreement to extend the period of operation of the Joint Defence Facility at Pine Gap Archived 6 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Report 26. Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, October 1999.

- 2002 Craig Skehan, "Pine Gap gears for war with eye on Iraq" Archived 4 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Sydney Morning Herald, 30 September 2002.

- 2003 Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Pine Gap Archived 22 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retranscription of program broadcast on 4 August 2003.

- 2007 Pine Gap 6

- 2007 "Judge rejects Pine Gap house arrest bid" The Australian, 29 May.

- 2007 "Aussies eye BMD role" United Press International, 11 Jun.

- 2007 "Pine Gap protest linked to Iraq war, pacifists tell court" ABC, Australia, 5 Jun.

- 2007 Protesters get a wrist slap Archived 18 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Pine Gap's wider missile role, The Age, 21 September 2007

- Pine Gap protests–historical at Nautilus Institute, April 2008

- Management of Operations at Pine Gap, Desmond Ball, Bill Robinson and Richard Tanter, Nautilus Institute, 24 November 2015

- The Base: Pine Gap's Role in US Warfighting, Background Briefing, ABC Radio National, 20 August 2017

- NSA Documents on Pine Gap, from archive of Edward Snowden, Background Briefing, ABC Radio National, 20 August 2017

- The U.S. Spy Hub in the Heart of Australia, The Intercept, 20 August 2017

- UKUSA listening stations

- Protests in Australia

- Earth stations in Australia

- Buildings and structures in Alice Springs

- Earth stations in the Northern Territory

- Australia–United States military relations

- Military installations of the United States in Australia

- 1970 establishments in Australia

- Australian intelligence agencies

- Australian Defence Force

- Military installations in the Northern Territory