Maken X

| Maken X | |

|---|---|

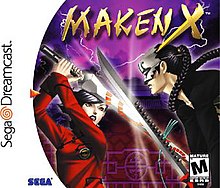

North American Dreamcast cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Atlus |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Director(s) | Katsura Hashino |

| Producer(s) | Kouji Okada |

| Designer(s) | Tatsuya Igarashi |

| Programmer(s) | Tai Yamaguchi (DC) Satoshi Ōyama (PS2) |

| Artist(s) | Kazuma Kaneko |

| Writer(s) | Kazunori Sakai |

| Composer(s) | Shoji Meguro Takahiro Ogata |

| Platform(s) | Dreamcast PlayStation 2 |

| Release | Maken XMaken Shao: Demon Sword |

| Genre(s) | Hack and slash |

| Mode(s) | Single player |

Maken X[a] is a first-person hack and slash video game developed by Atlus for the Dreamcast. It was published by Atlus in Japan in 1999, while Sega localized and released the game overseas in 2000. Gameplay has the Maken—a sentient sword-like being—"brainjacking" or taking control of multiple characters across a variety of levels; combat is primarily based around short-ranged melee attacks, with some characters sporting additional abilities such as ranged attacks.

The story is set on near-future Earth during a time when the world is descending into chaos due to natural disasters and political upheaval in Europe and rising political tension between the United States and China. When the facility where the Maken was developed is attacked, the sword bonds to main heroine Kay Sagami and is sent on missions against the group responsible for the attack. Depending on dialogue choices and brainjacked characters, seven possible endings can be achieved.

Concept work began during the middle of production on the Persona 2 duology. Featuring staff from the Megami Tensei franchise including artist Kazuma Kaneko and composer Shoji Meguro, development took approximately two years. It was the first game developed by Atlus to feature full voice acting, and one of the company's earliest fully 3D titles. The game was met with mixed reviews, but sold well in Japan. An enhanced remake for the PlayStation 2, Maken Shao: Demon Sword (魔剣 爻, Maken Shao), was published by Atlus in Japan in 2001 and in Europe by Midas Interactive Entertainment in 2003. It changed a number of gameplay elements, introduced further cutscenes, adjusted the music, and added the third-person perspective in response to a common trend in Japan of first-person games causing motion sickness.

Gameplay

Maken X is a first-person action hack and slash video game where players control a variety of characters wielding a sentient sword dubbed the Maken.[1][2] The game is divided into "Event Scenes", cutscenes related to the story; and "Action Scenes", the gameplay segments; and the world map used to select levels.[3] On the world map, players can select a variety of levels including main story missions, zones holding new playable characters, and levels involving key non-playable characters.[4] If the player character's health is fully depleted, the game ends.[3] Players take control of a number of people through the Maken's "brainjack" ability, enabling them to take control of different story-related characters; each character wields a version of the Maken, but also have unique abilities and different statistics such as higher health and greater attack power, or character-specific abilities such as ranged attacks or stunning enemies.[2][5][6]

Players navigate linear levels with the selected character, able to interact with certain environmental elements and jump over obstacles or onto higher platforms.[2][7] During combat, the player is able to move freely within the environment, and has access to a variety of moves including a back step and strafing to avoid attacks. Enemies encountered in areas include humans, hostile animals, machines, and supernatural entities. The player character, who can lock onto enemies during combat, has a standard attack option, with combos achieved through consecutive attacks. An "EX Gauge" can be charged up and released to trigger a powerful attack. The player can also leap over and strike an enemy from behind—these actions open the enemy up to a high-damage attack.[6][7][8] The player can find several types of items within each level; these include various sizes of life capsules which replenish health, increase attack power for a limited time, and gain PSI points from defeated enemies. PSI points are essential when brainjacking new characters, as the Maken can only brainjack a character with a lower or equivalent PSI level.[7]

For the remake Maken Shao, gameplay remains mostly the same, but with several added mechanics and a shift to a third-person perspective focused behind the back of the character. Combat options remain the same, but character abilities are now increased through combat by gaining "Image points", experience points earned from defeated enemies. After gathering enough Image points, new skills are unlocked for the current character, with the Maken's compatibility or "synchronization" with that character increasing alongside it; increased synchronization with a character raises their basic attributes such as health and attack power.[9]

Synopsis

Setting and characters

Maken X is set in a near-future version of Earth, described as "five minutes" into the future, the limit of precognitive vision. In the world of Maken X, the spirit is a scientifically-proven concept referred to as PSI, which arises from a separate dimension and is the source of emotion and sensation.[10][11] Amid rising tensions and flagging negotiations between the United States of America and the People's Republic of China, the European Union is collapsing due to growing misfortune across Europe.[10] Two key factions are the Blademasters, a society who maintain world peace at all costs and share a special gene dubbed the "D Gene"; and the Sangokai, a Hong Kong-based crime syndicate which splintered from the Blademasters and are responsible for the catastrophes engulfing the world. The Sangoki are led by the Hakke, humans with warped PSI that has malformed their bodies.[11] The central cast are staff at the Kazanawa Research Institute in Japan, which is secretly funded by the Blademasters from a base in China.[10]

The main protagonist is the Maken, an artificial being with direct access to the world of PSI. The Maken's key ability is "brainjack"; the Maken's native PSI is able to substitute itself for the PSI of a chosen host—referred to as their "Image"—giving the Maken control of that person's body. Given the default name "Deus Ex Machina", it was developed ostensibly as a means of treating mental illness, but is in fact a weapon for the Blademasters to defeat the Sangoki as it has the ability to destroy a person's Image.[11][12][13] The Maken's first and primary host is Kay Sagami; the daughter of the Institute's leader Hiro Sagami and a Chinese mother who died when Kay was still young, Kay dreams of following in her father's footsteps.[12][13] Supporting characters include Institute researchers Anne Miller and Peter Jones, Kay's childhood friend and love interest Kou Yamashiro; Blademaster leader Fu Shou Lee, who funds the Maken's creation; and Fei Chao Li, Kay's tutor and the intended wielder of the Maken due to possessing the Blademasters' D Gene.[12][13]

Plot

The game opens with the Maken's activation; Kay watches with her father as Fei prepares to wield the sword. They are attacked by Sangokai member Hakke Andrey, who kidnaps Sagami and mortally wounds Fei. Prompted by Fei before he dies, Kay takes up the Maken; brainjacking Kay, the Maken defeats Andrey, but fails to prevent Sagami from being kidnapped. Despite brainjacking Andrey to pursue the Sangokai under Lee's orders, Kay remains tied to the Maken and is in danger of permanently losing her PSI. During the Maken's journey across the world, it is revealed that the Sangokai—whose members include the current President of the United States—are being influenced by a god-like being of the PSI realm dubbed Geist. Geist, which also seeks to preserve humanity through more extreme means than the Blademasters, intends to use the Sangokai to reduce the human population. Over the course of the game, the Maken has the option of brainjacking numerous characters from both the Blademasters and the Sangokai.

Depending on brainjacking and dialogue choices made by the Maken through the game, several different narrative paths and endings are unlocked.[14] One ending has the Maken follow the Blademasters' orders, destroying the Sangokai and Geist while saving both Kay and Sagami; it is then sealed away as it has the potential of becoming a second Geist. Another ending sees the Maken allowing Kay to die, taking control of the American President following Geist's defeat. The third ending shows the Maken abandoning its mission in order to save Kay, which brings it into conflict with Geist—with the help of Kou, the Maken sacrifices itself and restores Kay to her body. Alternate versions of this route show the Maken being offered a deal by Geist if the Maken refuses to allow itself to die for Kay—accepting the truce restores Kay, while refusing it restores Sagami while the Maken permanently takes over Kay's body. Another route sees the Maken refuse to follow the Blademasters' orders and instead side with the Sangokai, killing Lee and joining Geist in creating a "utopia" by controlling human thoughts. If the Maken refuses to follow both the Blademasters and the Sangokai, it kills Geist while allowing Kay to die. The Maken is contacted by Lee's spirit, who says that the Maken is now the only being left capable of restoring the world.

Development

The concept for Maken X arose while Atlus was part of the way through developing the Persona 2 duology (Innocent Sin and Eternal Punishment) for the PlayStation.[15] Producer Kouji Okada was one of the original creators of Atlus' Megami Tensei series. Longtime Megami Tensei artist Kazuma Kaneko acted as art director and character designer.[15] The director was Katsura Hashino; having worked as a planner on multiple titles since Shin Megami Tensei If..., Maken X was his debut as a game director.[16] The game was developed by internal studio Atlus R&D1.[17] Most of the development team were directly carried over from the second Persona 2 game.[18] The Atlus staff were beginning to feel limited by the scope of the Megami Tensei universe, so when they were shown the specifications of the Dreamcast console, they immediately decided to create something new for that console.[19] Okada later said that Atlus' main desire when creating Maken X was to develop something new after making role-playing games for most of the company's lifetime.[18]

Speaking in an interview, Okada and Kaneko referred to the development period for Maken X as quite turbulent. Kaneko felt at first that the game was an "odd job", but over time he became deeply involved as the game graduated into being an important project for him. It was the first time the team had tried development with the Dreamcast, which proved more versatile and powerful than expected. The developers initially wanted a "neat" development project, but demands came for a more expansive project, resulting in the game's scale greatly increasing and the development process becoming chaotic, with more staff coming on board to help development. Due to these factors, the period of trial and error when creating the gameplay lasted much longer than intended.[15] The first-person perspective combined with sword-based action was chosen to create a unique feel for the game.[18] While 3D elements had been included in earlier Atlus titles, Maken X was the first time Atlus used both full 3D visuals and full-motion 3D CGI cutscenes.[20] The game was also the first time the Megami Tensei team had attempted development of a game outside the role-playing genre.[15]

Okada described the main theme as power achieved through intelligence and overcoming the environments.[19] The main narrative featured multiple references to Chinese mythology, while many of the player characters drew from historical and literary figures from each country the game visited. The Hakke leaders of the Sangokai were designed around a particular part of their body being malformed.[15][21] A narrative element carried over from the Megami Tensei franchise was a system of choices based on morality that influenced the ending; while these elements had been thoroughly explored in Megami Tensei, the team felt the themes still had potential and so used it in Maken X. The game was Atlus' first title to feature full voice acting; the team initially planned to voice event scenes in English and Chinese with Japanese subtitles, but included voice acting across the whole game due to positive feedback. A similar set of circumstances led to the wide use of stereophonic sound across the whole game when it was initially planned only for action sequences.[15]

Maken Shao: Demon Sword

Maken Shao: Demon Sword, known in Japan simply as Maken Shao,[b] was developed by Atlus for the PlayStation 2.[21] Okada, Hashino and Kaneko returned to their respective roles. The additional CGI segments were created by Polygon Magic.[16][21][22] While the basic gameplay and the original plot were carried over, several adjustments were made. The biggest change was a shift from a first-person to a third-person perspective; this was done due to a recurring problem with Japanese gamers dubbed "3D sickness", where people became motion sick when playing first-person games.[21] Another improvement was the sound environment, which made full use of Dolby Surround software.[23] The title's added "爻" character, an archaic Chinese symbol, was used as it represented two "X" characters, showing the game's status as an evolved version of Maken X.[21]

Music

The game's original score was composed by Shoji Meguro and Takahiro Ogata.[24] The musical style, which was described by Okada as "all techno music with heavy drumbeats", was intended to make the game feel "lively and fast".[18] Meguro worked on the soundtrack for around a year and a half, and composed most of the game's music, receiving some concepts for tunes and then being left to his own devices. He was faced with restrictions with the console's hardware, but was able to have more creative freedom than his work on Devil Summoner: Soul Hackers. The jazz-oriented ending theme, sung by Diana Leaves, was cited by Meguro as one of his favorite compositions from the game.[25] Due to his work, Meguro was unable to contribute to the Persona 2 duology at the time despite his previous involvement with Revelations: Persona.[26] Meguro returned to compose for Maken Shao, remixing many paces and adding additional musical elements.[21]

An official soundtrack was released by King Records in Japan on December 23, 1999.[27] An album of remixed tracks from the game by a number of guest musicians, Maken X Remix Soundtrack L'Image, released by Avex Mode on January 19, 2000.[28] The Maken X album, which became fairly rare in the years following its release, was later re-released by Atlus on iTunes on June 1, 2011. A new remix track was included as an exclusive to the digital album. Released alongside it was a mini-album of new and remixed music from Maken Shao, titled Maken Shao Mini Soundtrack and released to celebrate the game's tenth anniversary.[29]

Release

Maken X was first announced in November 1998.[30] Maken X was published by Atlus on November 25, 1999.[31] While Atlus' earlier Megami Tensei titles were aimed fully at the Japanese market, Maken X had been designed from the outset to have an international appeal.[18] Voice recording for the international release took place in North America. Meguro was involved in the process, which he stated was a positive experience.[25] The localization was handled cooperatively by Atlus and the American branch of Sega, who acted as the game's publishers.[19][32][33] The game's international release was announced in February 2000.[34] One of the points Atlus was concerned about for the international version was the use of Nazi imagery for some enemies. Due to what were described as "cultural points that could be harmful", the game's graphics were altered for the international release to avoid controversy. The gameplay remained unchanged between versions.[18][19] Kaneko described the voice recording as the most difficult part of the localization.[19] Initially scheduled for release in March, the game was pushed forward into April for unspecified reasons, although it was speculated that it was due to that month already boasting several game releases.[35] Maken X was eventually released in North America on April 25, 2000.[33] In Europe, the game was released on July 7 of that year.[1]

Maken Shao was first announced in February 2001. Prior to its official announcement, there was speculation that it was a sequel to the original game.[36] Maken Shao was published by Atlus in Japan on June 7, 2001. It came with both standard and limited editions, with the limited edition having exclusive cover art.[37] For its European release, DC Studios both converted Maken Shao to PAL region hardware, and localized the game into English.[38] It was published as Maken Shao: Demon Sword by Midas Interactive Entertainment on June 27, 2003.[39][40] This version was later re-released by Midas Interactive Entertainment on the European PlayStation Network on February 27, 2013 as a PlayStation Classic title.[41]

Adaptations

A manga adaptation written and illustrated by Q Hayashida was released between January 2000 and November 2001 by Kodansha. Titled Maken X: Another, the story followed a similar path to the original game.[42][43] The manga was collected into two volumes and released under the title Maken X: Another Jack by Enterbrain on December 25, 2008.[44][45] A comic anthology was published by Kodansha in March 2000.[46] A novelization titled Maken X: After Strange Days, written by Akira Kabuki and published by ASCII Media Works, was released in April 2000.[47]

Reception

| Aggregator | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Dreamcast | PS2 | |

| GameRankings | 71%[48] | N/A |

| Publication | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Dreamcast | PS2 | |

| AllGame | N/A | |

| CNET Gamecenter | 8/10[50] | N/A |

| Edge | 6/10[6] | N/A |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 5.83/10[51][c] | N/A |

| EP Daily | 5/10[52] | N/A |

| Famitsu | 32/40[53] | 32/40[54] |

| Game Informer | 7.75/10[55] | N/A |

| GameFan | (E.M.) 97%[56] (A.C.) 86%[57] | N/A |

| GameRevolution | C+[58] | N/A |

| GameSpot | 7.9/10[5] | N/A |

| GameSpy | 8/10[59] | N/A |

| IGN | 7.9/10[8] | N/A |

| Jeuxvideo.com | 15/20[60] | 9/20[61] |

| Next Generation | N/A | |

| Official Dreamcast Magazine (UK) | 85%[1] | N/A |

In Japan, the game received high scores from critics. The Japanese Dreamcast Magazine gave Maken X scores of 9, 9 and 7 out of 10 from three critics, placing it among the issue's highest-scoring games.[63] Famitsu gave the game a score of 32/40, consequently receiving the magazine's "Gold" award.[53] The remake Maken Shao received an identical score of 32/40 from Famitsu, which praised the overall gameplay and varied character choice.[54]

The game received above-average reviews internationally according to the review aggregation website GameRankings.[48] In an import review, Edge Magazine said that it was only the game's lack of multiplayer and level design that kept it from contending with the likes of GoldenEye 007, saying that it was otherwise a good Dreamcast game for adventure players.[6] In contrast, Lee Skittrell of Computer and Video Games felt it was not worth purchasing other than by those "desperate" for an action game due to the many faults he found.[64] James Mielke of GameSpot called Maken X a strong addition to the Dreamcast library and a good game in its own right,[5] IGN's Anoop Gantayat felt the game should be rented rather than immediately bought due to his own complaints,[8] while website GameRevolution said that Maken X was "one of those games that could have been great."[58] Eric Bratcher of NextGen said of the game, "There are redeeming elements, but they just don't resolve into anything exciting. We suggest waiting for Half-Life [Counter-Strike]."[62] GamePro, however, stated, "While this game doesn't fit neatly into any category – action, fighting, adventure, or role-playing – anyone who likes the idea of a pulse-pounding, arcade-style slasher with sweet graphics will enjoy hacking it up with Maken X."[65][d]

Nerys Coward of Official Dreamcast Magazine praised the story, calling it "theatrical and intriguing",[1] while in contrast Gantayat felt the storytelling was "poor" and faulted Sega's translation for further effecting it.[8] Edge Magazine noted the story's prominence set Maken X apart from equivalent first-person games of the time.[6] Skittrell was highly critical of the story segments as "boring [...] and far too long", but said the story was entertaining.[64] GameRevolution praised the unique choice of the Maken as protagonist along with the variety of endings.[58] The English voice acting was panned by multiple critics.[1][8][58]

Coward described the gameplay as highly enjoyable, praising the variety of playable characters but faulting the controls as stiff.[1] Edge praised the combat options and refreshing change from standard combat in other first-person games, noting the variety offered by character abilities but criticizing the lack of multiplayer options.[6] Mielke called the gameplay "pretty standard" aside from enemy variety and character options, and noted the light puzzle elements.[5] Skittrell generally found the game's substance lacking, but enjoyed the brainjacking feature.[64] Multiple reviewers faulted the controls as cumbersome or inappropriate for the gameplay.[1][5][8][64][58]

Coward praised the "slick and glitch-free" environments,[1] while Gantayat gave unanimous praise to both the game's graphics and its character designs.[8] Mielke gave particular praise to Kaneko's character designs, and like Coward noted the environments as being free of glitches and running smooth while maintaining quality.[5] Skittrell called the environmental graphics "super-crisp but lifeless and bland",[64] a sentiment shared by Edge.[6]

Upon its release in Japan, Maken X reached #6 in gaming charts. With sales of around 66,000 units, the game was the best-selling new Dreamcast release of the week, selling through nearly 73% of its shipments.[66][67] The game's total sales as of 2004 have reached over 70,800 units, ranking as the 50th best-selling Dreamcast game in Japan.[67] Maken Shao entered Japanese charts at #2, coming in behind Phantasy Star Online Ver 2 and ahead of the PlayStation port of Shin Megami Tensei.[68] Total sales for Maken Shao in Japan during 2001 stand at just over 40,000 units.[69]

Notes

- ^ (Japanese: 魔剣X, lit. Demon Sword X)

- ^ (魔剣爻, lit. Demon Sword Shao)

- ^ In Electronic Gaming Monthly's review of the game, one critic gave it a score of 5.5/10, and the rest gave it each a score of 6/10.

- ^ GamePro gave the game three 4.5/5 scores for graphics, control, and fun factor, and 4/5 for sound.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Coward, Nerys (October 2000). "Maken X" (PDF). Official Dreamcast Magazine (UK). No. 12. Dennis Publishing. pp. 62–63. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 2, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c Gantayat, Anoop (February 24, 2000). "Maken X (Preview)". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on August 17, 2002. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Sega, ed. (April 25, 2000). "The Game". Maken X instruction manual. pp. 10–11.

- ^ Sega, ed. (April 25, 2000). "World Map". Maken X instruction manual. p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f Mielke, James (December 8, 1999). "Maken X Review [JP Import] [date mislabeled as "April 28, 2000"]". GameSpot. Fandom. Archived from the original on December 9, 2004. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Edge staff (February 2000). "Maken X [JP Import]" (PDF). Edge. No. 81. Future Publishing. p. 85. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c Sega, ed. (April 25, 2000). Maken X instruction manual. pp. 16–20.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gantayat, Anoop (April 28, 2000). "Maken X". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on June 22, 2002. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ 魔剣爻 - ゲームの特徴. Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on December 22, 2002. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c Sega, ed. (April 25, 2000). "Prologue". Maken X instruction manual. pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c Sega, ed. (April 25, 2000). "Glossary". Maken X instruction manual. pp. 25–27.

- ^ a b c 魔剣X - キャラクター紹介. Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on June 20, 2001. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c Sega, ed. (April 25, 2000). "Character Introductions". Maken X instruction manual. pp. 21–26.

- ^ 魔剣X. Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on May 22, 2001. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f 魔剣X. Dreamcast Magazine (in Japanese). No. 37. SoftBank Creative. November 19, 1999. pp. 63–65.

- ^ a b Hashino, Katsura. 橋野 桂 [プロデューサー&ゲームディレクター] / スタッフ Voice. Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ Atlus (April 25, 2000). Maken X (Dreamcast). Sega. Scene: Credits.

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy, Sam (June 3, 1999). "GameSpot Talks to Legendary Atlus Producer [date mislabeled as "April 27, 2000"]". GameSpot. Fandom. Archived from the original on August 27, 1999. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "X Marks the Spot". Official Dreamcast Magazine (US). No. 4. Imagine Media. March 2000. p. 24. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ 魔剣X. Dreamcast Magazine (in Japanese). No. 22. SoftBank Creative. April 23, 1999. pp. 41–43.

- ^ a b c d e f 魔剣爻 公式ガイドブック [Maken Shao Official Guide Book] (in Japanese). Enterbrain. 2001. ISBN 4-7577-0519-0.

- ^ Atlus (July 26, 2003). Maken Shao: Demon Sword (PlayStation 2). Midas Interactive Entertainment. Scene: Credits.

- ^ 秋葉原で行われた『真・女神転生』、『魔剣爻』の発売記念イベントを密着レポート! (in Japanese). Dengeki Online. June 3, 2001. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ 魔剣X. Dreamcast Magazine (in Japanese). No. 53. SoftBank Creative. December 24, 1999. pp. 168–69.

- ^ a b "Shoji Meguro interview". RocketBaby. Archived from the original on August 26, 2002. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ^ ペルソナ公式パーフェクトガイド [Persona Official Perfect Guide] (in Japanese). Enterbrain. May 13, 2009. p. 355. ISBN 978-4-7577-4915-3.

- ^ "Maken X original sound tracks". VGMdb. Archived from the original on October 3, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ "Maken X Remix Soundtrack L'Image". VGMdb. Archived from the original on July 8, 2016. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ ATLUS MUSICにて「魔剣X」「ブレイズ・ユニオン」などの楽曲配信がスタート. 4Gamer.net (in Japanese). Aetas Inc. June 1, 2011. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ 魔剣X. Dreamcast Magazine (in Japanese). No. 4. SoftBank Creative. November 27, 1998. pp. 32–45.

- ^ [DC] 魔剣X. Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ Sega, ed. (April 25, 2000). Maken X instruction manual. p. 28.

- ^ a b GameSpot staff (April 25, 2000). "Sega Ships Two". GameSpot. Fandom. Archived from the original on June 8, 2000. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ IGN staff (February 3, 2000). "Maken X US Release Date Revealed". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ Gantayat, Anoop (February 29, 2000). "Maken X Gets Pushed Back". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ Gantayat, Anoop (February 14, 2001). "Latest Details: Maken Shao". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ [PS2] 魔剣爻(通常版). Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ "Products". DC Studios. Archived from the original on December 21, 2003. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ^ "Upcoming Products". Midas Interactive Entertainment. Archived from the original on June 24, 2003. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ "Maken Shao: Demon Sword - Related Games". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ Sahdev, Ishaan (February 14, 2013). "Atlus' Maken Shao Reaches PlayStation Network In Europe This Month". Siliconera. Enthusiast Gaming. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ 魔剣X ANOTHER(2). Kodansha (in Japanese). Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ 魔剣X ANOTHER(3). Kodansha (in Japanese). Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ 魔剣X Another Jack 1. Enterbrain (in Japanese). Archived from the original on December 9, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ 魔剣X Another Jack 2. Enterbrain (in Japanese). Archived from the original on December 9, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ 魔剣X. Kodansha (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2002-01-09. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- ^ 魔剣X : アフターストレンジデイズ. National Diet Library (in Japanese). Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "Maken X for Dreamcast". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ Knight, Kyle. "Maken X - Review". AllGame. All Media Network. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ D'Aprile, Jason (May 19, 2000). "Maken X". Gamecenter. CNET. Archived from the original on August 24, 2000. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ Kujawa, Kraig; Hager, Dean; MacDonald, Mark (June 2000). "Maken X" (PDF). Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 131. Ziff Davis. p. 161. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 8, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Conlin, Shaun (July 4, 2000). "Maken X". The Electric Playground. Greedy Productions Ltd. Archived from the original on May 23, 2004. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b ドリームキャスト - 魔剣X. Famitsu (in Japanese). No. 572. Enterbrain. 1999. p. 30. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b (PS2) 魔剣 爻(シャオ). Famitsu (in Japanese). Enterbrain. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ Fitzloff, Jay; Helgeson, Matt; Reiner, Andrew (June 2000). "Maken X". Game Informer. No. 86. FuncoLand. Archived from the original on December 2, 2000. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Mylonas, Eric "ECM" (February 2000). "Maken X [Import]". GameFan. Vol. 8, no. 2. Shinno Media. pp. 65–67. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Chau, Anthony (April 25, 2000). "REVIEW for Maken X". GameFan. Shinno Media. Archived from the original on May 11, 2000. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e G-Wok (April 2000). "Maken X Review". GameRevolution. CraveOnline. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ BenT (April 25, 2000). "Maken X". PlanetDreamcast. IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Kornifex (August 4, 2000). "Test: Maken X". Jeuxvideo.com (in French). Webedia. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Killy (November 13, 2003). "Test: Maken Shao: Demon Sword". Jeuxvideo.com (in French). Webedia. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Bratcher, Eric (July 2000). "Maken X". NextGen. No. 67. Imagine Media. p. 88. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ Williamson, Colin (November 19, 1999). "New Japanese Dreamcast Games Get Rated". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on June 3, 2002. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Skittrell, Lee (October 2000). "Maken X" (PDF). Computer and Video Games. No. 226. Future Publsihing. p. 112. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Jake The Snake (July 2000). "Maken X" (PDF). GamePro. No. 142. IDG. p. 92. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Langan, Matthew (December 6, 1999). "Japan Software Sales". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Sega Dreamcast Japanese Ranking". Japan Game Charts. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ 【メッセサンオー本店売り上げランキング(6/3~6/9調査)】文句なし!「PHANTASY STAR ONLINE Ver.2.0」がぶっちぎりトップ!!. ASCII Media Works (in Japanese). June 12, 2001. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ 2001年テレビゲームソフト売り上げTOP300. Geimin.net (in Japanese). Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

External links

- Japanese Dreamcast website (archived) (in Japanese)

- Japanese PlayStation 2 website (archived) (in Japanese)

- Maken X at MobyGames

- Maken Shao: Demon Sword at MobyGames

- 1999 video games

- Atlus games

- Dreamcast games

- First-person video games

- Hack and slash games

- Midas Interactive Entertainment games

- PlayStation 2 games

- PlayStation Network games

- Seinen manga

- Sega video games

- Single-player video games

- Video game remakes

- Video games about demons

- Video games developed in Japan

- Video games featuring female protagonists

- Video games scored by Shoji Meguro

- Video games set in Hong Kong

- Video games set in India

- Video games set in Moscow

- Video games set in Portugal

- Video games set in the future