Pinta Island tortoise

This article is missing information about full genome sequenced. (December 2020) |

| Pinta Island tortoise | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lonesome George at the Charles Darwin Research Station in 2006, the last known individual of his species of Galápagos tortoise | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Testudinidae |

| Genus: | Chelonoidis |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †C. n. abingdonii

|

| Trinomial name | |

| †Chelonoidis niger abingdonii | |

| |

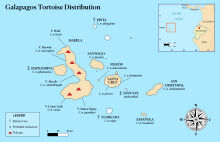

| Map of the Galápagos Islands showing locations of different tortoise species. | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

The Pinta Island tortoise[4] (Chelonoidis niger abingdonii[2][5]), also known as the Pinta giant tortoise,[2] Abingdon Island tortoise,[1] or Abingdon Island giant tortoise,[2] is a recently extinct subspecies of Galápagos tortoise native to Ecuador's Pinta Island.[1]

The subspecies was described by Albert Günther in 1877 after specimens arrived in London. By the end of the 19th century, most of the Pinta Island tortoises had been wiped out due to hunting.[6] By the mid-20th century, the subspecies was assumed to be extinct[7] until a single male was discovered on the island in 1971. Efforts were made to mate the male, named Lonesome George, with other subspecies, but no viable eggs resulted. Lonesome George died on 24 June 2012, and the subspecies was believed to have become extinct with his death.[8] However, 17 first-generation hybrids were reported in 2012 from Wolf Volcano on Isabela Island during a trip by Yale University researchers. As these specimens were juveniles, their parents might still be alive.[9][10] The subspecies is classified as extinct on the IUCN Red List.[1]

Taxonomy

Lonesome George, along with other of the tortoises on Pinta Island, belonged to a species of 15 subspecies. Giant tortoises were once found on all of the continents except Australia and Antarctica. The Galápagos tortoises remain the largest living tortoises.

The Pinta Island tortoise was originally described in 1877 by German-born British herpetologist Albert Günther, who named it Testudo abingdonii in his book The Gigantic Land-tortoises (Living and Extinct) in the Collection of the British Museum.[5][11] The name abingdonii derives from Abingdon Island, now more commonly known as Pinta Island. The knowledge of its existence was derived from short statements of the voyages of Captain James Colnett in 1798 and Basil Hall in 1822.[11] In 1876, Commander William Cookson[12] brought three male specimens (along with other subspecies of Galápagos tortoise) to London aboard the Royal Navy ship HMS Peterel.[11][13]

Synonyms of Chelonoidis abingdonii include Testudo abingdonii Günther, 1877; Testudo elephantopus abingdonii Mertens & Wermuth, 1955; Geochelone elephantopus abingdonii Pritchard, 1967; Geochelone nigra abingdonii Iverson, 1992; and Geochelone abingdonii Valverde, 2004.[3]

Evolution

The origin and systematic relationships are still unresolved today; they captivated Charles Darwin himself. DNA sequencing results indicate that the three best candidates for the closest living relative of the Galápagos tortoises all come from South America. They are the yellow-footed tortoise (Geochelone denticulata), the red-footed tortoise (Geochelone carbonaria), and the Chaco tortoise (Geochelone chilensis).[citation needed]

Behaviour and ecology

In the wild, Galápagos tortoises, including the Pinta Island subspecies, rested about 16 hours a day.[citation needed] Galápagos tortoises are herbivores, they fed primarily on greens, grasses, native fruit, and cactus pads. They drank large quantities of water, which they could store in their bodies for long periods of time for later use. They can reportedly survive up to six months without food or water.[14]

For breeding, the tortoises were most active during the hot season (January to May). During the cool season (June to November), female tortoises migrated to nesting zones to lay their eggs.

Galápagos giant tortoises represent the top herbivores in the Galápagos, and as such they shape the entire island ecosystem. They provide critical ecosystem services by dispersing seeds[15] and by acting as ecological engineers through herbivory and nutrient cycling. The extinction of the Pinta Island tortoise has diminished the functioning of the island ecosystem.[16]

Relationship with humans

Threats and conservation

Several of the surviving subspecies of Galápagos tortoises are endangered. The decline of the population began in the 17th century as a result of visits by buccaneers and whalers. They hunted tortoises as a source of fresh meat, taking about 200,000 tortoises altogether.

In 1958, goats were brought to Pinta Island and began eating much of the vegetation, to the detriment of the natural habitat.[17][18] A prolonged effort to exterminate the goats was begun. As the goat populations declined, the vegetation recovered. Small trees began regenerating from the stumps left by the goats. Highland shrub subspecies, forest tree seedlings, Opuntia cactus, and other endemic subspecies increased. In 2003, Pinta Island was declared goat-free.[19]

In addition to conservation efforts such as the elimination of goat populations in the Galápagos, there has been an effort to revive a number of subspecies of Galápagos tortoise through captive breeding. Future efforts may aim to recreate a population genetically similar to the original Pinta Island tortoise by breeding the first-generation hybrids discovered on Wolf Volcano.

Lonesome George

The last known individual of the subspecies was a male named Lonesome George[20] (Template:Lang-es),[21] who died on 24 June 2012.[7][22][23] In his last years, he was known as the rarest creature in the world. George served as a potent symbol for conservation efforts in the Galápagos and internationally.[24]

George was first seen on the island of Pinta on 1 December 1971 by Hungarian malacologist József Vágvölgyi. Relocated for his safety to the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz Island, George was penned with two females of different subspecies. Although the females laid eggs, none hatched. The Pinta tortoise was pronounced functionally extinct.

Over the decades, all attempts at mating Lonesome George were unsuccessful, possibly because his subspecies was not cross-fertile with the other subspecies.

On 24 June 2012, at 8:00 am local time, Director of the Galápagos National Park Edwin Naula announced that Lonesome George had been found dead[8][25][26] by his caretaker of 40 years, Fausto Llerena.[27] Naula suspects that the cause of death was heart failure consistent with the end of the natural life of a tortoise.

Possible remaining individuals

In 2006, Peter Pritchard, one of the world's foremost authorities on Galápagos tortoises, suggested that a male tortoise residing in the Prague Zoo might be a Pinta Island tortoise due to his shell structure.[28][29] Subsequent DNA analysis, however, revealed that it was more likely to be from Pinzón Island, home of the subspecies C. duncanensis.[2][29][30]

Whalers and pirates in the past used Isabela Island, the central and largest of the Galápagos Islands, as a tortoise dumping ground. Today, the remaining tortoises that live around Wolf Volcano have combined genetic markers from several subspecies.[31][32]

In May 2007, analysis of genomic microsatellites (DNA sequences) suggested that individuals from a translocated group of C. abingdonii may still exist in the wild on Isabela.[33] Researchers identified one male tortoise from the Wolf Volcano region that had half its genes in common with George's subspecies. This animal is believed to be a first-generation hybrid between the subspecies of the islands Isabela and Pinta.[33] This suggests the possibility of a pure Pinta tortoise among the 2,000 tortoises on Isabela.[34]

The identification of eight individuals of mixed ancestry among only 27 individuals sampled (estimated Volcano Wolf population size 1,000–2,000)… suggests the need to mount an immediate and comprehensive survey… to search for additional individuals of Pinta ancestry.[33]

A subsequent trip to Isabela by Yale University researchers found 17 first-generation hybrids living at Wolf Volcano.[9] The researchers planned to return to Isabela in the spring of 2013 to look for surviving Pinta tortoises and to try to collect hybrids in an effort to start a captive selective-breeding program and to hopefully reintroduce Pintas back to their native island.[9]

In 2020, the Galápagos national park and Galápagos Conservancy announced that they had discovered one young female with a direct line of descent from the Chelonoidis abingdonii subspecies of Pinta island. [35]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d Cayot, L.J.; Gibbs, J.P.; Tapia, W.; Caccone, A. (2016). "Chelonoidis abingdonii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T9017A65487433. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T9017A65487433.en. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ a b c d e van Dijk, Peter Paul; Iverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley; Bour, Roger; Rhodin, Anders G. J. (2011). "Turtles of the World, 2011 Update: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status". In Rhodin, Anders G.J.; Pritchard, Peter C. H.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Saumure, Raymond A.; Buhlmann, Kurt A.; Iverson, John B.; Mittermeier, Russell A. (eds.). Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises. Chelonian Research Monographs, Number 5. pp. 000.165 – 000.242. doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v4.2011. ISBN 978-0965354097. OCLC 472656069. S2CID 88917646.

- ^ a b "Chelonoidis abingdonii (GÜNTHER, 1877)". The Recently Extinct Plants and Animals Database. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ Reynolds, Robert P.; Marlow, Ronald W. (1983). "Lonesome George, the Pinta Island Tortoise: A Case of Limited Alternatives". Noticias de Galápagos. 37: 14–7. Archived from the original on 2017-10-28. Retrieved 2012-06-26.

- ^ a b Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of chelonians of the world". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 271. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. S2CID 87809001.

- ^ Nicholls, Henry (2007). Lonesome George: The Life and Loves of the World's Most Famous Tortoise. London: Pan Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-0330450119.

- ^ a b Hinckley, Story (2015-10-22). "14 animals declared extinct in the 21st century". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- ^ a b Jones, Bryony (25 June 2012). "Lonesome George, last of the Pinta Island tortoises, dies". CNN. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ a b c "Galapagos Tortoise 'Lonesome George' May Have Company". LiveScience. 2012-11-15. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ "Breeding Efforts May Resurrect Giant Tortoise Species - Island Conservation". Island Conservation. 2016-07-26. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ a b c Günther, Albert Carl Ludwig Gotthilf (1877). The gigantic land tortoises (living and extinct) in the collection of the British Museum. British Museum, Dept. of Zoology, London: Printed by order of the Trustees.

- ^ "William Edgar De Crackenthorpe Cookson R.N." William Loney RN - Background (Officers in command) – via pdavis.nl.

- ^ "HMS Peterel". William Loney RN - Background (Mid-Victorian RN vessels) – via pdavis.nl.

- ^ Caccone, Adalgisa; Gibbs, James P.; Ketmaier, Valerio; Suatoni, Elizabeth; Powell, Jeffrey R. (1999). "Origin and Evolutionary Relationships of Giant Galápagos Tortoises". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (23): 13223–13228. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9613223C. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.23.13223. PMC 23929. PMID 10557302.

- ^ Stephen Blake; Martin Wikelski; Fredy Cabrera; Anne Guezou; Miriam Silva; E. Sadeghayobi; Charles B. Yackulic; Patricia Jaramillo (2012). "Seed dispersal by Galapagos tortoises". Journal of Biogeography. 39 (11): 1961–1972. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02672.x. S2CID 52209043.

- ^ Edwards, Danielle; Benavides, Edgar; Garrick, Ryan (January 2013). "The genetic legacy of Lonesome George survives: Giant tortoises with Pinta Island ancestry identified in Galápagos". Biological Conservation. 157: 225–228. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.10.014.

- ^ "Galapagos Geology on the Web". Cornell University. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ Karl Campbell; C. Josh Donlan; Felipe Cruz; Victor Carrion (July 2004). "Eradication of feral goats Capra hircus from Pinta Island, Galápagos, Ecuador". Oryx. 38 (3). doi:10.1017/s0030605304000572. S2CID 247105.

- ^ "Lonesome George". Galapagos Conservancy. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ Gardner, Simon (2001-02-06). "Lonesome George faces own Galapagos tortoise curse". Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2012-01-11.

- ^ Proceso de Relaciones Públicas de la Dirección del Parque Nacional Galápagos (2012-06-24). "El mundo pierde al solitario George". Archived from the original on 2012-06-28. Retrieved 2012-06-25.

- ^ "Lonesome George, last-of-his-kind Galapagos tortoise, dies". The Times of India. 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- ^ Raferty, Isolde. "Lonesome George, last-of-its-kind Galapagos tortoise, dies". MSNBC. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- ^ Nicholls, Henry (2006). Lonesome George: The Life and Loves of a Conservation Icon. London: Macmillan Science. ISBN 978-1-4039-4576-1.[page needed]

- ^ "Giant tortoise Lonesome George's death leaves the world one subspecies poorer". National Post. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ Alexandra Valencia; Eduardo Garcia (2012-06-25). "Lonesome George, last-of-his-kind Galapagos tortoise, dies". Reuters. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ "Muere el Solitario George, la última tortuga gigante de isla Pinta". El Unveriso. Archived from the original on 2013-01-15. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- ^ Sulloway, Frank J. (2006-07-28). "Is Lonesome George Really Lonesome?". ESKEPTIC: The Email Newsletter of the Skeptics Society. ISSN 1556-5696.

- ^ a b Nicholls, Henry (2007). Lonesome George: The Life and Loves of the World's Most Famous Tortoise. London: Pan Books. p. 142. ISBN 978-0330450119.

- ^ Russello, M. A. (2007). "Lineage identification of Galápagos tortoises in captivity worldwide". Animal Conservation. 10 (3): 304–311. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2007.00113.x. S2CID 85200951.

- ^ Marshall, Michael (2012-06-26). "Lonesome George dies but his subspecies genes survive". New Scientist.

- ^ Nicholls, Henry (2007-06-06). "Galapagos tortoises: untangling the evolutionary threads". New Scientist.

- ^ a b c Russello, Michael A.; Beheregaray, Luciano B.; Gibbs, James P.; Fritts, Thomas; Havill, Nathan; Powell, Jeffrey R.; Caccone, Adalgisa (1 May 2007). "Lonesome George is not alone among Galápagos tortoises". Current Biology. 17 (9): R317 – R318. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.002. PMID 17470342. S2CID 3055405.

- ^ "Iconic tortoise George may not be last of his kind". ABC News. Agence France-Presse. 2007-05-01. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ "Galápagos experts find a tortoise related to Lonesome George". The Guardian. Associated Press. 2020-02-02. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

Bibliography

- Caccone, Adalgisa; Gibbs, James P.; Ketmaier, Valerio; Suatoni, Elizabeth; Powell, Jeffrey R. (1999-11-09). "Origin and evolutionary relationships of giant Galápagos tortoises". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (23): 13223–13228. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9613223C. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.23.13223. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 23929. PMID 10557302.

- Nicholls, Henry (2004-06-03). "Tortoise conservation: One of a kind". Nature. 429 (6991): 498–500. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..498N. doi:10.1038/429498a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15175722. S2CID 32875557.

- Giant Tortoises Archived 2015-10-15 at the Wayback Machine, Galapagos Conservancy

- Recovery of a nearly extinct Galápagos tortoise despite minimal genetic variation., Wiley Online Library

External links

- Naked Scientists audio discussion of Lonesome George

- Article on Lonesome George The giant tortoise of Galapagos Island.

- Lonesome George, by Vicky Seal

- "Team of Veterinarians Prepare Hybrid Tortoises for Release on Pinta Island in 2010" (Press release). Galapagos Conservancy. 2010-02-03. Archived from the original on 2010-02-08.

- Garrick, Ryan C.; Benavides, Edgar; Russello, Michael A.; Gibbs, James P.; et al. (2012). "Genetic rediscovery of an 'extinct' Galápagos giant tortoise species". Current Biology. 22 (1): R10–1. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.004. PMID 22240469.