Grimoire

A grimoire (/ɡrɪmˈwɑːr/) (also known as a "book of spells", "magic book", or a "spellbook")[citation needed] is a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms, and divination, and how to summon or invoke supernatural entities such as angels, spirits, deities, and demons.[1] In many cases, the books themselves are believed to be imbued with magical powers, although in many cultures, other sacred texts that are not grimoires (such as the Bible) have been believed to have supernatural properties intrinsically. The only contents found in a grimoire would be information on spells, rituals, the preparation of magical tools, and lists of ingredients and their magical correspondences.[2][unreliable source?] In this manner, while all books on magic could be thought of as grimoires, not all magical books should be thought of as grimoires.[3]

While the term grimoire is originally European—and many Europeans throughout history, particularly ceremonial magicians and cunning folk, have used grimoires—the historian Owen Davies has noted that similar books can be found all around the world, ranging from Jamaica to Sumatra.[4] He also noted that in this sense, the world's first grimoires were created in Europe and the ancient Near East.[5]

Etymology

The etymology of grimoire is unclear. It is most commonly believed that the term grimoire originated from the Old French word grammaire 'grammar', which had initially been used to refer to all books written in Latin. By the 18th century, the term had gained its now common usage in France and had begun to be used to refer purely to books of magic. Owen Davies presumed this was because "many of them continued to circulate in Latin manuscripts".[6]

However, the term grimoire later developed into a figure of speech among the French indicating something that was hard to understand. In the 19th century, with the increasing interest in occultism among the British following the publication of Francis Barrett's The Magus (1801), the term entered English in reference to books of magic.[1]

History

Ancient period

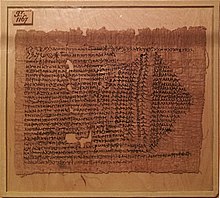

The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), where they have been found inscribed on cuneiform clay tablets that archaeologists excavated from the city of Uruk and dated to between the 5th and 4th centuries BC.[7] The ancient Egyptians also employed magical incantations, which have been found inscribed on amulets and other items. The Egyptian magical system, known as heka, was greatly altered and expanded after the Macedonians, led by Alexander the Great, invaded Egypt in 332 BC.[8]

Under the next three centuries of Hellenistic Egypt, the Coptic writing system evolved, and the Library of Alexandria was opened. This likely had an influence upon books of magic, with the trend on known incantations switching from simple health and protection charms to more specific things, such as financial success and sexual fulfillment.[8] Around this time the legendary figure of Hermes Trismegistus developed as a conflation of the Egyptian god Thoth and the Greek Hermes; this figure was associated with writing and magic and, therefore, of books on magic.[9]

The ancient Greeks and Romans believed that books on magic were invented by the Persians. The 1st-century AD writer Pliny the Elder stated that magic had been first discovered by the ancient philosopher Zoroaster around the year 647 BC but that it was only written down in the 5th century BC by the magician Osthanes. His claims are not, however, supported by modern historians.[10]

The ancient Jewish people were often viewed as being knowledgeable in magic, which, according to legend, they had learned from Moses, who had learned it in Egypt. Among many ancient writers, Moses was seen as an Egyptian rather than a Jew. Two manuscripts likely dating to the 4th century, both of which purport to be the legendary eighth Book of Moses (the first five being the initial books in the Biblical Old Testament), present him as a polytheist who explained how to conjure gods and subdue demons.[9]

Meanwhile, there is definite evidence of grimoires being used by certain—particularly Gnostic—sects of early Christianity. In the Book of Enoch found within the Dead Sea Scrolls, for instance, there is information on astrology and the angels. In possible connection with the Book of Enoch, the idea of Enoch and his great-grandson Noah having some involvement with books of magic given to them by angels continued through to the medieval period.[10]

"Many of those [in Ephesus] who believed [in Christianity] now came and openly confessed their evil deeds. A number who had practised sorcery brought their scrolls together and burned them publicly. When they calculated the value of the scrolls, the total came to fifty thousand drachmas. In this way the word of the Lord spread widely and grew in power."

Acts 19, c. 1st century

Israelite King Solomon was a Biblical figure associated with magic and sorcery in the ancient world. The 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian Josephus mentioned a book circulating under the name of Solomon that contained incantations for summoning demons and described how a Jew called Eleazar used it to cure cases of possession. The book may have been the Testament of Solomon but was more probably a different work.[11] The pseudepigraphic Testament of Solomon is one of the oldest magical texts. It is a Greek manuscript attributed to Solomon and was likely written in either Babylonia or Egypt sometime in the first five centuries AD; over 1,000 years after Solomon's death.

The work tells of the building of The Temple and relates that construction was hampered by demons until the archangel Michael gave the King a magical ring. The ring, engraved with the Seal of Solomon, had the power to bind demons from doing harm. Solomon used it to lock demons in jars and commanded others to do his bidding, although eventually, according to the Testament, he was tempted into worshiping "false gods", such as Moloch, Baal, and Rapha. Subsequently, after losing favour with God, King Solomon wrote the work as a warning and a guide to the reader.[12]

When Christianity became the dominant faith of the Roman Empire, the early Church frowned upon the propagation of books on magic, connecting it with paganism, and burned books of magic. The New Testament records that after the unsuccessful exorcism by the seven sons of Sceva became known, many converts decided to burn their own magic and pagan books in the city of Ephesus; this advice was adopted on a large scale after the Christian ascent to power.[13]

Medieval period

In the Medieval period, the production of grimoires continued in Christendom, as well as amongst Jews and the followers of the newly founded Islamic faith. As the historian Owen Davies noted, "while the [Christian] Church was ultimately successful in defeating pagan worship it never managed to demarcate clearly and maintain a line of practice between religious devotion and magic."[14] The use of such books on magic continued. In Christianised Europe, the Church divided books of magic into two kinds: those that dealt with "natural magic" and those that dealt in "demonic magic".[15]

The former was acceptable because it was viewed as merely taking note of the powers in nature that were created by God; for instance, the Anglo-Saxon leechbooks, which contained simple spells for medicinal purposes, were tolerated. Demonic magic was not acceptable, because it was believed that such magic did not come from God, but from the Devil and his demons. These grimoires dealt in such topics as necromancy, divination and demonology.[15] Despite this, "there is ample evidence that the mediaeval clergy were the main practitioners of magic and therefore the owners, transcribers, and circulators of grimoires,"[16] while several grimoires were attributed to Popes.[17]

One such Arabic grimoire devoted to astral magic, the 10th-century Ghâyat al-Hakîm, was later translated into Latin and circulated in Europe during the 13th century under the name of the Picatrix.[18] However, not all such grimoires of this era were based upon Arabic sources. The 13th-century Sworn Book of Honorius, for instance, was (like the ancient Testament of Solomon before it) largely based on the supposed teachings of the Biblical king Solomon and included ideas such as prayers and a ritual circle, with the mystical purpose of having visions of God, Hell, and Purgatory and gaining much wisdom and knowledge as a result. Another was the Hebrew Sefer Raziel Ha-Malakh, translated in Europe as the Liber Razielis Archangeli.[19]

A later book also claiming to have been written by Solomon was originally written in Greek during the 15th century, where it was known as the Magical Treatise of Solomon or the Little Key of the Whole Art of Hygromancy, Found by Several Craftsmen and by the Holy Prophet Solomon. In the 16th century, this work had been translated into Latin and Italian, being renamed the Clavicula Salomonis, or the Key of Solomon.[20]

In Christendom during the medieval age, grimoires were written that were attributed to other ancient figures, thereby supposedly giving them a sense of authenticity because of their antiquity. The German abbot and occultist Trithemius (1462–1516) supposedly had a Book of Simon the Magician, based upon the New Testament figure of Simon Magus.[21]

Similarly, it was commonly believed by medieval people that other ancient figures, such as the poet Virgil, astronomer Ptolemy, and philosopher Aristotle, had been involved in magic, and grimoires claiming to have been written by them were circulated.[22] However, there were those who did not believe this; for instance, the Franciscan friar Roger Bacon (c. 1214–94) stated that books falsely claiming to be by ancient authors "ought to be prohibited by law."[23]

Early modern period

As the early modern period commenced in the late 15th century, many changes began to shock Europe that would have an effect on the production of grimoires. Historian Owen Davies classed the most important of these as the Protestant Reformation, and subsequent Catholic Counter-Reformation; The Witch-hunts, and the advent of printing. The Renaissance saw the continuation of interest in magic that had been found in the Medieval period, and in this period, there was an increased interest in Hermeticism among occultists and ceremonial magicians in Europe, largely fueled by the 1471 translation of the ancient Corpus hermeticum into Latin by Marsilio Ficino (1433–99).

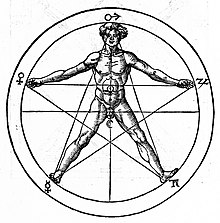

Alongside this, there was a rise in interest in the Jewish mysticism known as the Kabbalah, which was spread across the continent by Pico della Mirandola and Johannes Reuchlin.[24] The most important magician of the Renaissance was Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (1486–1535), who widely studied occult topics and earlier grimoires and eventually published his own, the Three Books of Occult Philosophy, in 1533.[25] A similar figure was the Swiss magician known as Paracelsus (1493–1541), who published Of the Supreme Mysteries of Nature, in which he emphasised the distinction between good and bad magic.[26] A third such individual was Johann Georg Faust, upon whom several pieces of later literature were written, such as Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, that portrayed him as consulting with demons.[27]

The idea of demonology had remained strong in the Renaissance, and several demonological grimoires were published, including The Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy, which falsely claimed to having been authored by Cornelius Agrippa,[28] and the Pseudomonarchia Daemonum, which listed 69 demons. To counter this, the Roman Catholic Church authorised the production of many works of exorcism, the rituals of which were often very similar to those of demonic conjuration.[29] Alongside these demonological works, grimoires on natural magic continued to be produced, including Magia Naturalis, written by Giambattista Della Porta (1535–1615).[30]

Iceland held magical traditions in regional work as well, most remarkably the Galdrabók, where numerous symbols of mystic origin are dedicated to the practitioner. These pieces give a perfect fusion of Germanic pagan and Christian influence, seeking splendid help from the Norse gods and referring to the titles of demons.[31]

The advent of printing in Europe meant that books could be mass-produced for the first time and could reach an ever-growing literate audience. Among the earliest books to be printed were magical texts. The nóminas were one example, consisting of prayers to the saints used as talismans.[32] It was particularly in Protestant countries, such as Switzerland and the German states, which were not under the domination of the Roman Catholic Church, where such grimoires were published.

Despite the advent of print, however, handwritten grimoires remained highly valued, as they were believed to contain inherent magical powers, and they continued to be produced.[33] With increasing availability, people lower down the social scale and women began to have access to books on magic; this was often incorporated into the popular folk magic of the average people and, in particular, that of the cunning folk, who were professionally involved in folk magic.[34] These works left Europe and were imported to the parts of Latin America controlled by the Spanish and Portuguese empires and the parts of North America controlled by the British and French empires.[35]

Throughout this period, the Inquisition, a Roman Catholic organisation, had organised the mass suppression of peoples and beliefs that they considered heretical. In many cases, grimoires were found in the heretics' possessions and destroyed.[36] In 1599, the church published the Indexes of Prohibited Books, in which many grimoires were listed as forbidden, including several mediaeval ones, such as the Key of Solomon, which were still popular.[37]

In Christendom, there also began to develop a widespread fear of witchcraft, which was believed to be Satanic in nature. The subsequent hysteria, known as The Witch-hunts, caused the death of around 40,000 people, most of whom were women.[38] Sometimes, those found with grimoires—particularly demonological ones—were prosecuted and dealt with as witches but, in most cases, those accused had no access to such books. Iceland—which had a relatively high literacy rate—proved an exception to this, with a third of the 134 witch trials held involving people who had owned grimoires.[39] By the end of the Early Modern period, and the beginning of the Enlightenment, many European governments brought in laws prohibiting many superstitious beliefs in an attempt to bring an end to the Witch Hunts; this would invariably affect the release of grimoires.

Meanwhile, Hermeticism and the Kabbalah would influence the creation of a mystical philosophy known as Rosicrucianism, which first appeared in the early 17th century, when two pamphlets detailing the existence of the mysterious Rosicrucian group were published in Germany. These claimed that Rosicrucianism had originated with a Medieval figure known as Christian Rosenkreuz, who had founded the Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross; however, there was no evidence for the existence of Rosenkreuz or the Brotherhood.[40]

18th and 19th centuries

The 18th century saw the rise of the Enlightenment, a movement devoted to science and rationalism, predominantly amongst the ruling classes. However, amongst much of Europe, belief in magic and witchcraft persisted,[41] as did the witch trials in certain[which?] areas. Governments tried to crack down on magicians and fortune tellers, particularly in France, where the police viewed them as social pests who took money from the gullible, often in a search for treasure. In doing so, they confiscated many grimoires.[42]

Beginning in the 17th century, a new, ephemeral form of printed literature developed in France; the Bibliothèque bleue. Many grimoires published through this circulated among a growing percentage[citation needed] of the populace; in particular, the Grand Albert, the Petit Albert (1782), the Grimoire du Pape Honorius, and the Enchiridion Leonis Papae. The Petit Albert contained a wide variety of magic; for instance, dealing in simple charms for ailments, along with more complex things, such as the instructions for making a Hand of Glory.[43]

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, following the French Revolution of 1789, a hugely influential grimoire was published under the title of the Grand Grimoire, which was considered[by whom?] particularly powerful, because it involved conjuring and making a pact with the devil's chief minister, Lucifugé Rofocale, to gain wealth from him. A new version of this grimoire was later published under the title of the Dragon rouge and was available for sale in many Parisian bookstores.[44] Similar books published in France at this time included the Black Pullet and the Grimoirium Verum. The Black Pullet, probably authored in late-18th-century Rome or France, differs from the typical grimoires in that it does not claim to be a manuscript from antiquity, but told by a man who was a member of Napoleon's armed expeditionary forces in Egypt.[45]

The widespread availability of printed grimoires in France—despite the opposition of both the rationalists and the church—soon[when?] spread to neighbouring countries, such as Spain and Germany. In Switzerland, Geneva was commonly associated with the occult at the time, particularly by Catholics, because it had been a stronghold of Protestantism. Many of those interested in the esoteric traveled from Roman Catholic nations to Switzerland to purchase grimoires or to study with occultists.[46] Soon, grimoires appeared that involved Catholic saints; one example that appeared during the 19th century, and became relatively popular—particularly in Spain—was the Libro de San Cipriano, or The Book of St. Ciprian, which falsely claimed to date from c. 1000. As with most grimoires of this period, it dealt with (among other things) how to discover treasure.[47]

In Germany, with the increased interest in folklore during the 19th century, many historians took an interest in magic and in grimoires. Several published extracts of such grimoires in their own books on the history of magic, thereby helping to further propagate them. Perhaps the most notable of these was the Protestant pastor Georg Conrad Horst (1779–1832) who, from 1821 to 1826, published a six-volume collection of magical texts in which he studied grimoires as a peculiarity of the Medieval mindset.[48]

Another scholar of the time interested in grimoires, the antiquarian bookseller Johann Scheible first published the Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses; two influential magical texts that claimed to have been written by the ancient Jewish figure Moses.[49] The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses were among the works which later spread to the countries of Scandinavia, where—in Danish and Swedish—grimoires were known as black books and were commonly found among members of the army.[50]

In Britain, new grimoires continued to be produced throughout the 18th century, such as Ebenezer Sibly's A New and Complete Illustration of the Celestial Science of Astrology. In the last decades of that century, London experienced a revival of interest in the occult which was further propagated by Francis Barrett's publication of The Magus in 1801. The Magus contained many things taken from older grimoires—particularly those of Cornelius Agrippa—and, while not achieving initial popularity upon release, it gradually became an influential text.[51]

One of Barrett's pupils, John Parkin, created his own handwritten grimoire The Grand Oracle of Heaven, or, The Art of Divine Magic, although it was never published, largely because Britain was at war with France, and grimoires were commonly associated with the French. The only writer to publish British grimoires widely in the early 19th century was Robert Cross Smith, who released The Philosophical Merlin (1822) and The Astrologer of the Nineteenth Century (1825), but neither sold well.[52]

In the late 19th century, several of these texts (including The Book of Abramelin and the Key of Solomon) were reclaimed by para-Masonic magical organisations, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the Ordo Templi Orientis.

20th and 21st centuries

The Secret Grimoire of Turiel claims to have been written in the 16th century, but no copy older than 1927 has been produced.[53]

A modern grimoire, the Simon Necronomicon, takes its name from a fictional book of magic in the stories of H. P. Lovecraft which was inspired by Babylonian mythology and the Ars Goetia—one of the five books that make up The Lesser Key of Solomon—concerning the summoning of demons. The Azoëtia of Andrew D. Chumbley has been described by Gavin Semple as a modern grimoire.[54]

The neopagan religion of Wicca publicly appeared in the 1940s, and Gerald Gardner introduced the Book of Shadows as a Wiccan grimoire.[55]

The term grimoire commonly serves as an alternative name for a spell book or tome of magical knowledge in fantasy fiction and role-playing games. The most famous fictional grimoire is the Necronomicon, a creation of H. P. Lovecraft.[55]

See also

- Table of magical correspondences, a type of reference work used in ceremonial magic

- Codex

References

- ^ a b Davies (2009:1)

- ^ "Grimoire vs Book of Shadows".

- ^ Davies (2009:2–3)

- ^ Davies (2009:2–5)

- ^ Davies (2009:6–7)

- ^ Davies, Owen (2009). Grimoires : a history of magic books. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199204519. OCLC 244766270.

- ^ Davies (2009:8)

- ^ a b Davies (2009:8–9)

- ^ a b Davies (2009:10)

- ^ a b Davies (2009:7)

- ^ Butler, E. M. (1979). "The Solomonic Cycle". Ritual Magic (Reprint ed.). CUP Archive. ISBN 0-521-29553-X.

- ^ Davies (2009:12–13)

- ^ Davies (2009:18–20)

- ^ Davies (2009:21–22)

- ^ a b Davies (2009:22)

- ^ Davies (2009:36)

- ^ Davies (2009:34–35)

- ^ Davies (2009:25–26)

- ^ Davies (2009:34)

- ^ Davies (2009:15)

- ^ Davies (2009:16–17)

- ^ Davies (2009:24)

- ^ Davies (2009:37)

- ^ Davies (2009:46)

- ^ Davies (2009:47–48)

- ^ Davies (2009:48)

- ^ Davies (2009:49–50)

- ^ Davies (2009:51–52)

- ^ Davies (2009:59–60)

- ^ Davies (2009:57)

- ^ Stephen Flowers (1995). The Galdrabók: An Icelandic Grimoire. Rûna-Raven Press.

- ^ Davies (2009:45)

- ^ Davies (2009:53–54)

- ^ Davies (2009:66–67)

- ^ Davies (2009:84–90)

- ^ Davies (2009:54–55)

- ^ Davies (2009:74)

- ^ Patrick, J. (2007). Renaissance and Reformation. Marshall Cavendish. p. 802. ISBN 978-0-7614-7650-4. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Davies (2009:70–73)

- ^ Davies (2009:47)

- ^ Hsia, R. Po-chia (15 April 2008). A Companion to the Reformation World. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-7865-5.

- ^ Davies (2007:95–96)

- ^ Davies (2007:98–101)

- ^ Davies (2007:101–104)

- ^ Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2006). "grimoire". The Encyclopedia of Magic and Alchemy. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1-4381-3000-7.

- ^ Davies (2007:109–110)

- ^ Davies (2007:114–115)

- ^ Davies (2007:121–122)

- ^ Davies (2007:123)

- ^ Davies (2007:134–136)

- ^ Davies (2007:123–124)

- ^ Davies (2007:135–137)

- ^ Malchus, Marius (2011). The Secret Grimoire of Turiel. Theophania Publishing. ISBN 978-1-926842-80-6.

- ^ Semple, Gavin (1994) 'The Azoëtia – reviewed by Gavin Semple', Starfire Vol. I, No. 2, 1994, p. 194.

- ^ a b Davies, Owen (4 April 2008). "Owen Davies's top 10 grimoires". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

Bibliography

- Davies, Owen (2009). Grimoires: A History of Magic Books. Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 9780199204519. OCLC 244766270.

External links

Media related to Grimoires at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Grimoires at Wikimedia Commons- Internet Sacred Text Archives: Grimoires

- Digitized Grimoires

- Reidar Thoralf Christiansen; Pat Shaw Iversen (1964). Folktales of Norway. University of Chicago Press. p. 32ff. ISBN 978-0-226-10510-9.

- Scandinavian folklore Archived 21 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine