Sodasa

| Sodasa | |

|---|---|

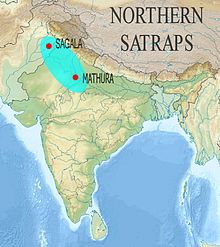

| Indo-Scythian Northern Satraps king | |

| |

| Reign | c. 15 CE |

| Predecessor | Rajuvula |

| Father | Rajuvula |

| Mother | Kamuia Ayasa |

Svāmisya Mahakṣatrapasya Śudasasya

"Of the Lord and Great Satrap Śudāsa"[2]

Sodasa (Middle Brahmi script: ![]()

![]()

![]() Śodāsa, also

Śodāsa, also ![]()

![]()

![]() Śudāsa) was an Indo-Scythian Northern Satrap and ruler of Mathura during the later part of the 1st century BCE or the early part of 1st century CE.[3] He was the son of Rajuvula, the Great Satrap of the region from Taxila to Mathura.[4] He is mentioned in the Mathura lion capital.[5]

Śudāsa) was an Indo-Scythian Northern Satrap and ruler of Mathura during the later part of the 1st century BCE or the early part of 1st century CE.[3] He was the son of Rajuvula, the Great Satrap of the region from Taxila to Mathura.[4] He is mentioned in the Mathura lion capital.[5]

Rule

Sodasa reigned during the 1st century CE, and also took the title of Great Satrap at one point, probably in the area of Mathura as well, but possibly under the suzerainty of the Indo-Parthian king Gondophares. At the same time the Indo-Scythian Bhadayasa ruled in the eastern Punjab.[3] There were numerous cultural and political exchanges between the Indo-Scythians of the northwest and those of Mathura.[3]

Sodasa may have been a contemporary of the Western Kshatrapa Nahapana and the Indo-Parthian Gondophares.[3] The Indo-Parthians may have destabilized Indo-Scythian rule in northern India, but there are no traces of Indo-Parthian presence in Mathura.[3] Sodasa may have been displaced in Mathura by the Kushan ruler Vima Kadphises, who erected a throne in his name in Mathura, but nothing is known of these interactions.[3]

At Mathura, Sodasa is the last of the Indo-Scythians to have left coins.[3] Later, under Kanishka, son of Vima Kadphises, the Great Satrap Kharapallana and the Satrap Vanaspara are said to have ruled in Mathura with Kanishka as suzerain, pointing to continued Indo-Scythian rule under Kushan suzerainty as least until the time of Kanishka.[6][7][8][9]

Inscriptions

Numerous inscriptions from Mathura mentioning Sodasa's rule are known. The Mirzapur village inscription (in the vicinity of Mathura) refers to the erection of a water tank by Mulavasu and his consort Kausiki during the reign of Sodasa, assuming the title of "Svami (Lord) Mahakshatrapa (Great Satrap)".[2]

The Mathura lion capital mentions the reign of his father and predecessor Rajuvula as Mahaksatrapa while Sodasa is referred to as Ksatrapa. Sodasa probably also dedicated the Mora Well Inscription, were he presents himself as the son of Rajuvula.[10]

A large stone slab, the Kankali Tila tablet of Sodasa, discovered in Kankali in the area of Mathura, bears a three-line epigraph mentioning that in the year 42 or 72 of "Lord Mahaksatrapa Sodasa," a monument for worship was set up by a certain Amohini.[11] A recent date for Sodasa's reign was given as 15 CE, meaning that the regnal date of the inscription would start from the Vikrama era (Bikrami calendar (starting in 57 BCE)+72=15 CE).[12][13] This would put the long reign of his father Rajuvula in the last quarter of the 1st century BCE, which is probable.[13]

Another inscription of Sodasa in Mathura records the gifts of a Brahman named Gajavara of the Segrava-gotra during the time of Saudasa the Great Satrap of the lord (paramount, whose name is lost) of tanks called Kshayawada, as well as a western tank, a well, a garden, and a pillar.[14]

- Mathura inscription mentioning the rule of Sodasa as Kshatrapa (Satrap) or Mahakshatrapa (Great Satrap).

-

The Mathura lion capital mentions Sodasa as "Satrap", while his father Rajuvula was "Great Satrap".

-

Mirzapur stele inscription of Sodasa's Reign, Mirzapur area of Mathura. Mathura Museum. The inscription refers to the erection of a water tank by Mulavasu and his consort Kausiki, during the reign of Sodasa, assuming the title of "Svami (Lord) Mahakshatrapa (Great Satrap)":[2][15][16]

-

The Kankali Tila tablet of Sodasa with an inscription mentioning the year 42 or 72 during the reign of Sodasa as Makakshatrapa (Great Satrap).[11]

-

Another inscription of Sodasa in Mathura. This inscription records the gifts of a Brahman named Gajavara of the Segrava-gotra during the time of Saudasa the Great Satrap of the lord (paramount, whose name is lost) of tanks called Kshayawada, besides a western tank, a well, a garden, and a pillar.[14]

-

Kankali Tila inscription of Sodasa (from the Kankali Tila tablet of Sodasa). This inscription mentions the rule of Svamisa Mahakṣatrapasa Śodasa (

"Of the Lord and Great Satrap Śudāsa") from the beginning of the second line.[17]

"Of the Lord and Great Satrap Śudāsa") from the beginning of the second line.[17] -

Mountain Temple inscription mentioning Sodasa and his father Rajuvula

-

Mora Well Inscription in the name of Rajuvula and his son Sodasa.

Coinage

Sodasa's coins have been found in Mathura only, suggesting that he only ruled over the Mathura region.[18] They do not follow traditional Indo-Scythian coinage patterns, but rather the designs of local rulers of Mathura, and are only made of lead and copper alloy.[18] The legends only use the Indian Brahmi script, whether Saodasa's father Rajuvula had used coins derived from the Indo-Greeks, with legends in Greek and Kharoshthi.[18] This suggests that Sodasa had significantly integrated into the local Indian culture.[18]

Sodasa's coins usually show on the obverse a standing female and tree-like symbol, with the legend "Mahakatapasa putasa Khatapasa Sodasa", i.e., "Satrap Sodasa, son of the Great Satrap". On the reverse appears a Lakshmi with elephants pouring water over her.[1][18]

Three types of legends are known, with one coin type of Sodasa bearing the legend "son of Rajuvula":

- "Satrap Sodasa, son of the Great Satrap" (Mahakhatapasa putasa khatapasa śodasasa followed by a svastika)[18]

- "Satrap Sodasa, son of Rajuvula" (Svastika followed by Rajuvula putasa khatapasa śodasasa)[18][3]

- "Great Satrap Sodasa" (Mahakhatapasa śodasasa)[18]

-

Coin of Sodasa. Reverse: "Mahakshatrapa putasa Khatapasa Sodasasa" ("Satrap Sodasa, son of the Great Satrap")

-

Coin of Sodasa, satrap of Mathura, AE.

Obv: Lakshmi standing between two symbols on the obverse and inscription around "Mahakhatapasa putasa Khatapasa Sodasasa ".

Rev: Standing Abhiseka Lakshmi anointed by two elephants.

Sculptural styles

The abundance of dedicatory inscriptions in the name of Sodasa (eight of them are known, often on sculptural works), and the fact that Sodasa is known through his coinage as well as through his relations with other Indo-Scythian rulers whose dates are known, means that Sodasa functions as a historic marker to ascertain the sculptural styles at Mathura during his rule, in the first half of the 1st century CE.[22] The next historial marker corresponds to the reign of Kanishka under the Kushans, whose reign began circa 127 CE.[22]

The Kankali Tila tablet of Sodasa is one of those sculptural works directly inscribed in the name of Sodasa.[22] Another one is the Katra torana fragment.[22][23][24] The sculptural styles at Mathura during the reign of Sodasa are quite distinctive, and significantly different from the style of the previous period circa 50 BCE, or the styles of the later period of the Kushan Empire in the 2nd century CE.[22] Stylistically similar works can then be dated to the same period of the reign of Sodasa.[22]

Early representation of the Buddha

The "Isapur Buddha" from Mathura, probably the earliest known representation of the Buddha (possibly together with Buddha statues found in Barikot in Swat), on a railing post, is dated to circa 15 CE under the reign of Sodasa.[25] Another depiction of the Buddha from the same period apppears in the Bimaran casket.

Paleography

The inscriptions in the name of Sodasa are also an important marker for the paleography of the Brahmi script, the shape of the Brahmi letters having evolved in time, and also having varied depending on the regions.[26]

References

- ^ a b Catalogue Of The Coins In The Indian Museum Calcutta. Vol.1 by Smith, Vincent A. p.196

- ^ a b c Buddhist art of Mathurā , Ramesh Chandra Sharma, Agam, 1984 Page 26

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Dynastic art of the Kushans, Rosenfield, University of California Press, 1967 p.136

- ^ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 170. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ^ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. pp. 168–169. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ^ Aspects of Political Ideas and Institutions in Ancient India, Ram Sharan Sharma, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1991 p.295 [1]

- ^ Ancient Indian History and Civilization, Sailendra Nath Sen New Age International, 1999, p.198 [2]

- ^ Foreign Influence on Ancient India, Krishna Chandra Sagar, Northern Book Centre, 1992 p.167 [3]

- ^ Source: "A Catalogue of the Indian Coins in the British Museum. Andhras etc..." Rapson, p ciii

- ^ Chakravarti, N. p (1937). Epigraphia Indica Vol.24. p. 194.

- ^ a b The Jain stûpa and other antiquities of Mathurâ by Smith, Vincent Arthur Plate XIV

- ^ Image Problems: The Origin and Development of the Buddha's Image in Early South Asia Robert Daniel DeCaroli, University of Washington Press, 2015 p.205

- ^ a b Indian Studies, Volume 7, Ramakrishna Maitra, 1966 p.67

- ^ a b Report For The Year 1871-72 Volume III, Alexander Cunningham

- ^ History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE by Sonya Rhie Quintanilla p.260

- ^ Epigraphia Indica, Vol 40

- ^ Chandra, Ramaprasad (1919). Memoirs of the archaeological survey of India no.1-5. p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 169. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ^ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. pp. 199–206, 204 for the exact date. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ^ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 171. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ^ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. pp. 174–176. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ^ a b c d e f Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. pp. 168–179. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ^ Photograph visible p.396 in Zin, Monika (2015). In her right hand she held a silver knife with small bells... (PDF). Studies in Indian Culture and Literature, Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 396.

- ^ Photograph (front) Photograph (reverse)

- ^ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. pp. 199–206, 204 for the exact date. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ^ Kumar, Ajit (2014). "Bharhut Sculptures and their untenable Sunga Association". Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology. 2: 223–241.

![Mirzapur stele inscription of Sodasa's Reign, Mirzapur area of Mathura. Mathura Museum. The inscription refers to the erection of a water tank by Mulavasu and his consort Kausiki, during the reign of Sodasa, assuming the title of "Svami (Lord) Mahakshatrapa (Great Satrap)":[2][15][16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Inscription_of_Sodasha_Reign_-_Circa_1st_Century_BCE_-_Mirzapur_-_ACCN_79-29_-_Government_Museum_-_Mathura_2013-02-24_6105.JPG/552px-Inscription_of_Sodasha_Reign_-_Circa_1st_Century_BCE_-_Mirzapur_-_ACCN_79-29_-_Government_Museum_-_Mathura_2013-02-24_6105.JPG)

![The Kankali Tila tablet of Sodasa with an inscription mentioning the year 42 or 72 during the reign of Sodasa as Makakshatrapa (Great Satrap).[11]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1f/Amohini_relief%2C_Mathura%2C_circa_15_CE.jpg/270px-Amohini_relief%2C_Mathura%2C_circa_15_CE.jpg)

![Another inscription of Sodasa in Mathura. This inscription records the gifts of a Brahman named Gajavara of the Segrava-gotra during the time of Saudasa the Great Satrap of the lord (paramount, whose name is lost) of tanks called Kshayawada, besides a western tank, a well, a garden, and a pillar.[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/Satrap_Saudasa_inscription.jpg/368px-Satrap_Saudasa_inscription.jpg)

![Kankali Tila inscription of Sodasa (from the Kankali Tila tablet of Sodasa). This inscription mentions the rule of Svamisa Mahakṣatrapasa Śodasa ( "Of the Lord and Great Satrap Śudāsa") from the beginning of the second line.[17]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/14/Kankali_Tila_inscription_of_Sodasa.jpg/824px-Kankali_Tila_inscription_of_Sodasa.jpg)