A Short Film About Killing

| A Short Film About Killing | |

|---|---|

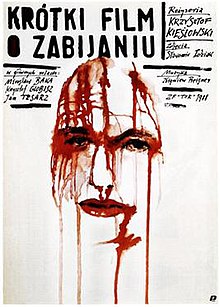

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Krzysztof Kieślowski |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Ryszard Chutkowski |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Sławomir Idziak |

| Edited by | Ewa Smal |

| Music by | Zbigniew Preisner |

Production company | Zespoły Filmowe "Tor" |

| Distributed by | Film Polski |

Release date |

|

Running time | 84 minutes |

| Country | Poland |

| Language | Polish |

A Short Film About Killing (Template:Lang-pl) is a 1988 drama film directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski and starring Mirosław Baka, Krzysztof Globisz, and Jan Tesarz. Written by Krzysztof Kieślowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz, the film was expanded from Dekalog: Five of the Polish television series Dekalog. Set in Warsaw, Poland, the film compares the senseless, violent murder of an individual to the cold, calculated execution by the state.[1] A Short Film About Killing won both the Jury Prize and the FIPRESCI Prize at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival,[2] as well as the European Film Award for Best Film.[3]

Plot

Waldemar Rekowski (Jan Tesarz) is a middle-aged taxicab driver in Warsaw who enjoys his profession and the freedom it affords. His concern for turning a profit leads him to ignore some potential fares in favor of others. An overweight and crude man, Waldemar also enjoys staring at young women. Jacek Łazar (Mirosław Baka) is a 21-year-old drifter who recently arrived in Warsaw from the countryside and is now aimlessly wandering the streets of the city. He seems to take pleasure in causing other people's misfortunes: he throws a stranger into the urinals of a public toilet after being approached sexually; he drops a large stone from a bridge onto a passing vehicle causing an accident; and he scares away pigeons to spite an old lady who was feeding them. Piotr Balicki (Krzysztof Globisz) is a young and idealistic lawyer who has just passed the bar exam. He takes his wife to a café where they discuss their future. At the same café, Jacek is sitting at a table handling a length of rope and a stick which he keeps in his bag. The rope and stick appear to be a weapon. He puts away the rope and stick when he spots two girls playing at the other side of the window and he engages in a game with them.

One of the most crucial moments that relates to the encounter with the young girls is Jacek's sister's death. He goes to a photographer to have her first communion picture blown up despite its wear and tear damage. This is the focal point of Jacek's trauma, which is brought up during his conversation with the young lawyer. It may also be construed as a redeeming value to his character/persona, as he seems to be deeply affected by his little sister's death, as well as his mother's suffering. Jacek holds on to his sister's memory and the love for his mother by asking Piotr to retrieve the blow-up of his sister's picture from the photographer, as he gives Piotr the receipt, and give the picture to his mother, so she has something to hold on to after having two of her children killed.

Meanwhile, Waldemar has been driving his taxicab around the city looking for a fare. He stops near the café just as Jacek approaches and enters the cab. He asks to be driven to a remote part of the city near the countryside and insists the driver take a longer and more remote route. At their destination, Jacek tries to kill Waldemar with the rope, but stops and hides when people approach. The driver is still breathing and tries unsuccessfully to remove the rope from his neck. Jacek then completes his gruesome task by repeatedly smashing the barely conscious taxicab driver over the head with a large rock. Jacek then takes the taxicab to the river and dumps the body. When a children's song comes on the radio, he gets upset, rips out the radio, and discards it. He drives the car to a grocery store where he talks to a girl who jumps into the car. She notices a clown's head hanging from the mirror and asks Jacek where he got the car. He suggests that they could go away together, but she keeps asking where the car comes from as a taxi driver with the same car was trying to flirt with her earlier the same day.

Sometime later, Jacek is caught and imprisoned. He is interviewed by his criminal defense lawyer, Piotr, for whom this is his first case after finishing his legal studies. Piotr has little chance of winning the case against Jacek because of the strong evidence against his client. In spite of Piotr's efforts, Jacek is found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. Piotr approaches a judge afterwards asking if he could've done more to save his client's life. The judge assures him that Piotr gave the best argument against the death penalty he's heard in years, but that the legal outcome is correct.

On the appointed day, the executioner arrives at the jail and prepares for the hanging. Piotr is at the prison to attend the execution, and an official congratulates him on having just become a father. In the moments before his execution, Jacek reveals to Piotr that his baby sister was killed by a tractor driven by his drunken friend, and that he was drinking with him; he says he never fully recovered from the tragic episode. Jacek then requests that he be given the final space in his family's grave which was reserved for his mother—that he be buried next to his sister and his father. The warden repeatedly asks if they are finished talking; Piotr defiantly says he will never be finished. Jacek makes some petty last requests to his lawyer. They conclude things would've turned out differently if the girl had not tragically died.

Jacek is then taken from his cell and marched to the execution chamber by several prison guards. The confirmation of his sentence is read to him as well as the decision to deny clemency. He is given last rites by a priest, and offered a final cigarette by the warden. When he requests to have one without filter instead, the executioner steps forward, lights one of his cigarettes and puts it into Jacek's mouth. Jacek takes a few puffs before it is stubbed out. Just before he is hanged, he breaks free from his guards and begins to yell uncontrollably before his hands are shackled and he is quickly hanged with ruthless efficiency. Afterwards, Piotr drives to an empty field where he sobs.

Cast

- Mirosław Baka as Jacek Lazar

- Krzysztof Globisz as Piotr Balicki (Advocate)

- Jan Tesarz as Waldemar Rekowski (Taxi driver)

- Zbigniew Zapasiewicz as Committee Chairman

- Barbara Dziekan as Cashier

- Aleksander Bednarz as The Executioner

- Jerzy Zass as Police Commander

- Zdzisław Tobiasz as Judge

- Artur Barciś as Young Man

- Krystyna Janda as Dorota

- Olgierd Łukaszewicz as Andrzej

- Peter Falchi as British Motorist

- Elzbieta Helman as Beatka

- Maciej Maciejewski as Prosecutor[4]

Background

The film shows a very bleak Poland near the end of the Communist era. This is greatly enhanced by the strong use of colour filters. The print appears to have an effect similar to sepia tone or bleach bypass—although it is a colour picture, the photography combined with grey locations provides an effect similar to monochrome.

A Short Film About Killing was released in the same year that the death penalty was suspended in Poland. In 1988 the country carried out just a single execution, with 6 condemned prisoners being hanged in 1987. The portrayal of the execution method and procedure is mostly accurate, however in reality the date of executions were a surprise to the prisoner—the condemned man would simply be led into a room to discover it was the execution chamber. After the early years of Communist repression, executions were quite rare and invariably for murder; from 1969 a total of 183 men were hanged and no women.

Themes

- Social class

In her article about the film, Janina Falkowska describes the brutality of the effects class societies have on the lower class, emphasizing on the "hopelessness" of the latter and false hope of the former.[5]

- Law and politics

Falkowska also talks about the law as a personified entity—capable of being both just and unjust, responsible for saving and ruining lives. Its integrity is thus significant to the fate of the protagonist.[5]

- Death and mutiny

Cine-literacy author Charles V. Eidsvik suggests there is a "presence of senseless malice in the film", a notion reiterated in the forms of death and mutiny.[6]

Style

Dehumanizing filters were used to distort the images of Warsaw, creating a raw, unattractive image. Kieślowski credits his cinematographer, Slawomir Idziak, for this deliberate visual unattractiveness within the film, stating: "I sense that the world is becoming more and more ugly. . . . I wanted to dirty this world. . . . We used green filters that give this strange effect, allowing us to mask all that isn’t essential to the image".[7] When Kieslowski first showed Idziak the screenplay, he commented, saying, "I can’t even read this! It disgusts me," and then finally conceded, "I’ll shoot it only on the condition that you let me do it green and use all my filters, with which I’ll darken the image." Kieslowski was not pleased, but he accepted the ultimatum, telling Idziak, "if you want to make green shit, it’s your affair." The cinematographer concluded, "That’s how the graphic concept came about which Cahiers Du Cinema wrote that it was the most originally shot movie in the Cannes Film Festival."[8] Idziak also used a hand held camera when filming; this gave an added raw feel to the film as it follows the daily routines of the film's protagonist.

Production

Filming locations

The film was shot on location in Warsaw and Siedlce. Like the gloomy events portrayed in the film, the capital city of Warsaw is depicted as a repellent, depressing place: grey, brutal and peopled by alienated characters. Several areas of the city were used:[9]

- Krakowskie Przedmieście, Sródmiescie, Warsaw, Mazowieckie, Poland

- Old Town, Śródmieście, Warsaw, Mazowieckie, Poland

- Siedlce, Mazowieckie, Poland

- Warsaw, Mazowieckie, Poland[10]

Reception

Critical response

The Polish premiere coincided with a heated debate in Poland about capital punishment. Although the film's diegesis does not directly address political events, it is unanimously interpreted as a political statement. The Polish audience did not like the parallel alluded to between a murder committed by an individual and a murder committed by the state. Despite this controversy, the majority of critics praised Kieslowski's film and it was nominated for and won a multitude of awards.[11]

Sight & Sound magazine conducts a poll of film directors every ten years to find out what they consider the ten greatest films of all time. In 2012, Cyrus Frisch voted for A Short Film About Killing. Frisch commented: "In Poland, this film was instrumental in the abolition of the death penalty."[12] The film is among 21 digitally restored classic Polish films chosen for Martin Scorsese Presents: Masterpieces of Polish Cinema.[13]

Awards and nominations

- 1988 Cannes Film Festival FIPRESCI Prize (Krzysztof Kieślowski) Won

- 1988 Cannes Film Festival Jury Prize (Krzysztof Kieślowski) Won

- 1988 Cannes Film Festival Nomination for the Palme d'Or (Krzysztof Kieślowski)

- 1988 European Film Award for Best Film (Krzysztof Kieślowski) Won

- 1988 Polish Film Festival Golden Lion Award (Krzysztof Kieślowski) Won

- 1990 Bodil Award for Best European Film (Krzysztof Kieślowski) Won

- 1990 French Syndicate of Cinema Critics Award for Best Foreign Film (Krzysztof Kieślowski) Won

- 1990 Robert Festival Award for Best Foreign Film (Krzysztof Kieślowski) Won[3]

Differences with Dekalog: Five

According to the funding deal that Kieślowski had with TV Poland to make Dekalog, two of the episodes would be expanded into films. Kieslowski himself selected Dekalog: Five, leaving the second for the Polish ministry of culture. The Ministry selected Dekalog: Six and funded both productions.[9]

The cinematic release of Dekalog: Five: A Short film about killing, premiered in Polish cinemas in March 1988.

Although the main plot in both works is the same, Dekalog: Five has a different order in editing and makes more use of voice-over, whereas the film starts differently and gives a more prominent role to Piotr, the lawyer. Dekalog: Five suddenly jumps from the killing scene to jail and there is no connection or explanation on how Jacek got arrested. A few scenes and lines of dialogue do not feature in Dekalog: Five, to keep it within the time limitations for TV as intended.

See also

References

- ^ "A Short Film About Killing". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ "A Short Film About Killing". Festival de Cannes. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Awards for A Short Film About Killing". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ "Full cast and crew for A Short Film About Killing". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ a b Falkowska, J. (Winter 1995). "'The Political' in the Films of Andrzej Wajda and Krzysztof Kieslowski" in Cinema Journal. 34 (2), pp. 37-50.

- ^ Eidsvik, Charles (Fall 1990) "Kieslowski's Short Films" in Film Quarterly. Found here: http://www.petey.com/kk/docs/shorts1.txt

- ^ Haltof, Marek (2004) the cinema of Krzysztof Kieślowski: variations on destiny and chance (London: Wallflower Press). Pp. 92-93

- ^ Insdorf, Annette (1999). Double Lives, Second Chances: The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieślowski. New York: Hyperion, p. 95.

- ^ a b Haltof, Marek (2004) the cinema of Krzysztof Kieślowski: variations on destiny and chance (London: Wallflower Press)

- ^ "Filming locations for A Short Film About Killing". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ Falkowska, J. (winter, 1995). "The Political in the Films of Andrzej Wajda and Krzysztof Kieslowski. Cinema journal . 34 (2), pp.37-50.

- ^ http://explore.bfi.org.uk/sightandsoundpolls/2012/voter/920

- ^ Martin Scorsese Presents: Masterpieces of Polish Cinema

External links

- 1988 films

- 1988 crime drama films

- Polish films

- Polish crime drama films

- Polish-language films

- Films about capital punishment

- European Film Awards winners (films)

- Films set in Poland

- Films set in Warsaw

- Films scored by Zbigniew Preisner

- Capital punishment in Poland

- Films directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski

- Films with screenplays by Krzysztof Piesiewicz

- Films with screenplays by Krzysztof Kieślowski

- Films based on television series