42nd Regiment of Foot

| 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot | |

|---|---|

Cap badge of the 42nd Regiment of Foot | |

| Active | 1661–1718 1725–1881 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Line Infantry |

| Garrison/HQ | Queen's Barracks, Perth |

| Nickname(s) | Black Watch Forty-Twa Black Jocks |

| Motto(s) | (Scotland's) Nemo me impune lacessit |

| Engagements | |

| Battle honours | |

The 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot was a Scottish infantry regiment in the British Army also known as the Black Watch. Originally titled Crawford's Highlanders or the Highland Regiment and numbered 43rd in the line, in 1748, on the disbanding of Oglethorpe's Regiment of Foot, they were renumbered 42nd and in 1751 formally titled the 42nd (Highland) Regiment of Foot. The 42nd Regiment was one of the first three Highland Regiments to fight in North America.[1] [2] In 1881 the regiment was named The Royal Highland Regiment (The Black Watch), being officially redesignated The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) in 1931. In 2006 the Black Watch became part of the Royal Regiment of Scotland.

History

Early history

After the Jacobite rising of 1715 the British government did not have the resources or manpower to keep a standing army in the Scottish Highlands. As a result, they were forced to keep order by recruiting men from local Highland clans that had been loyal to the Whigs. This proved to be unsuccessful in deterring crime, especially cattle rustling. Therefore, Independent Highland Companies (of what would be known as the "Black Watch") were raised as a militia in 1725 by General George Wade to keep "watch" for crime.[4] He was commissioned to build a network of roads to help in the task.[5] The six Independent Highland Companies were recruited from local clans, with one company coming from Clan Munro, one from Clan Fraser of Lovat, one from Clan Grant and three from Clan Campbell. These companies were commonly known as Am Freiceadan Dubh, or the Black Watch, this name may well have been due to the way they dressed.[6] Four more companies were added in 1739 to make a total of ten Independent Highland Companies.[7]

The ten Independent Highland Companies of "Black Watch" were officially formed into the "43rd Highland Regiment of Foot", a regiment of the line in 1739.[7] It was first mustered in 1740, at Aberfeldy, Scotland. The Colonel was John Lindsay, 20th Earl of Crawford and the Lieutenant-Colonel was Sir Robert Munro, 6th Baronet. Among the Captains were his next brother, George Munro, 1st of Culcairn (also a Captain of an Independent Company raised in 1745) and their cousin John Munro, 4th of Newmore, who was promoted Lieutenant-Colonel in 1745 (in place of Sir Robert who went on to command the 37th (North Hampshire) Regiment of Foot). The other Captains of the 43rd were George Grant, Colin Campbell of Monzie, James Colquhoun of Luss, John Campbell of Carrick, Collin Campbell of Balliemore and Dougal Campbell of Craignish.[8]

First action and mutiny

In March 1743, the regiment was assembled at Perth in preparation for moving to London, then Flanders to join British forces fighting in the War of the Austrian Succession. Scottish officials, including the Lord President of the Court of Session, Duncan Forbes warned the government this was contrary to a general understanding their service was restricted to Scotland. Assured the move was only because George II wanted to inspect them, they arrived in London in May and were then ordered to Gravesend for shipment to Flanders. Anger at the deception, allied to rumours they were going to the West Indies, a location notorious for high mortality rates, caused a mutiny; they set out for Scotland, led by Corporals Malcolm and Samuel MacPherson and Private Farquhar Shaw.[9] They reached Ladywood on the outskirts of Oundle, Northamptonshire on 22 May before being intercepted. The mutineers surrendered in hope of a free pardon, but were marched back to London and incarcerated in the Tower of London. The three leaders of the mutiny were subsequently court-martialled and executed by firing squad on 18 July 1743, at Tower Green. Two hundred other members of the regiment were distributed variously to garrisons in Jamaica, Gibraltar and Menorca, with the remainder shipped to Flanders.[10][11]

The regiment's first full combat was the disastrous Battle of Fontenoy in May 1745, where they surprised the French with their ferocity, and greatly impressed their commander, the Duke of Cumberland.[12] Allowed "their own way of fighting", each time they received the French fire Colonel Sir Robert Munro ordered his men to "clap to the ground" while he himself, because of his corpulence, stood alone with the colours behind him.[11]

When the Jacobite rising of 1745 broke out, another three companies were raised in Scotland, one being present at the Battle of Prestonpans in September 1745 where the entire company was either killed or taken prisoner.[13] Another fought for the government under Dugald Campbell of Auchrossan at the Battle of Culloden in April 1746 where they suffered no casualties.[14][15] These three companies were disbanded in 1748.[16]

The rest of the regiment landed in England on 4 November and remained there in anticipation of a possible French invasion until after the rebellion ended. From early 1747 to the end of 1748, it was in Flanders but otherwise was stationed in Ireland until 1756. In 1749, after Oglethorpe's Regiment of Foot was disbanded and the Black Watch was re-numbered the 42nd and in 1751 formally titled the 42nd (Highland) Regiment of Foot.[17] On the outbreak of the Seven Years' War in 1756, it was sent to North America.[18]

The Americas

During the French and Indian War, at the first battle of Ticonderoga, also known as the Battle of Carillon, the regiment lost over half of its men in the assault in July 1758.[19][20] At that time they were already officially recognized as a Royal regiment.[21] The second battalion of the Black Watch was sent to the Caribbean[22] but after the losses of Ticonderoga, the two battalions were consolidated in New York. The regiment was present at the second battle of Ticonderoga in July 1759 and the surrender of Montreal in September 1760. They were sent to the West Indies again where they saw action at Havana, Martinique and Guadeloupe.[11]

Between 1758 and 1767 the 42nd served in America. In August 1763, the regiment fought in the Battle of Bushy Run while trying to relieve Fort Pitt, modern Pittsburgh, during Pontiac's Rebellion.[23] The regiment went to Cork, Ireland in 1767 and returned to Scotland in 1775.[11]

During the American Revolutionary War, the regiment was involved in the defeat of George Washington in the Battle of Long Island in August 1776[24] and saw combat at the Battle of Harlem Heights in September 1776, the Battle of Fort Washington in November 1776 and the Battle of Piscataway in February 1777. It also fought at the Battle of Brandywine (light infantry and grenadier companies only) in September 1777,[25] the Battle of Germantown (Light Company only) in October 1777[26] and the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778 as well as the Siege of Charleston in spring 1780.[27] In September 1778 a detachment from the regiment raided Fairhaven, Massachusetts, inflicting severe damage on the town's shipping industry.[11]

Following the end of the war in America, the 42nd were posted to Nova Scotia in 1783,[28] serving there until 1786 when they moved north to Cape Breton Island. The regiment returned to England in 1789.[29] Landing at Portsmouth, they marched to Tynemouth in Northumberland and in the spring of 1790 marched on to Glasgow, before taking up residence at Edinburgh Castle in November 1790.[30]

French Revolutionary Wars

During the battle of Alexandria in 1801 a major in the regiment captured a standard from the French. They went on to besiege Cairo and then Alexandria in which the French forces were expelled from Egypt.[11]

Peninsular War

The 1st battalion embarked for Portugal in August 1808 for service in the Peninsular War.[31] At the Battle of Corunna in January 1809[32] it was a soldier of the 42nd Highlanders who carried the mortally wounded General Sir John Moore to cover, and six more who carried him to the rear, but only after he had witnessed the victory in which the stout defence of the Black Watch played a major part. Moore's army was evacuated from Spain and the 1st Battalion of the 42nd Highlanders went with them.[11]

As the 1st battalion left, the 2nd battalion was dispatched from Ireland to Spain for service in the Peninsular War. The 2nd battalion fought at the Battle of Bussaco in September 1810[33] before falling back to the Lines of Torres Vedras.[34] The 2nd battalion fought with great distinction at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro in May 1811,[34] the Siege of Ciudad Rodrigo in January 1812[35] and the bloody Siege of Badajoz in March 1812[35] before returning home to recruit.[36] The 1st battalion returned to the Peninsula in time to fight in the Battle of Salamanca in July 1812,[36] the Siege of Burgos in September 1812[37] and the Battle of Vitoria in June 1813.[37] It then pursued the French Army into France and fought at the Battle of the Pyrenees in July 1813,[38] the Battle of Nivelle in November 1813[39] and the Battle of the Nive in December 1813[39] before seeing action at the Battle of Orthez in February 1814[40] and the Battle of Toulouse in April 1814.[40]

Waterloo

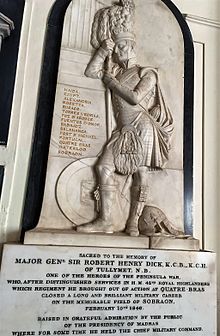

With the war with France now apparently over, the 2nd battalion was disbanded in 1814 and some of its number transferred to the permanent 1st battalion. The now single battalion 42nd fought at the chaotic Battle of Quatre Bras on 16 June 1815[41] under Lieutenant-colonel Sir Robert Macara, who was killed by French lancers.[42] The 42nd was one of four battalions mentioned by Wellington in despatches after the battle. Two days later at the Battle of Waterloo,[43] the 42nd and also the 2nd/73rd Highlanders, which was later to become the new 2nd Battalion, Black Watch, were both in some of the most intense fighting in the battle.[11]

The Victorian era

The regiment formed part of the Highland Brigade at the Battle of Alma in September 1854 and the Siege of Sevastapol in winter 1854 during the Crimean War; it also formed part of that brigade at the Siege of Cawnpore in June 1857 and the siege of Lucknow in autumn 1857 during the Indian Rebellion.[11] During the Siege of Cawnpore the regiment captured a gong which has tolled the hours in the regiment's guardroom ever since.[44]

As part of the Cardwell Reforms of the 1870s, where single-battalion regiments were linked together to share a single depot and recruiting district in the United Kingdom, the 40th was linked with the 79th Regiment of Foot (Cameronian Volunteers), and assigned to district no. 57 at Queen's Barracks in Perth.[45] On 1 July 1881 the Childers Reforms came into effect and the regiment amalgamated with the 73rd (Perthshire) Regiment of Foot to form the Black Watch (Royal Highlanders).[11]

Popular culture

A number of songs were composed about the regiment including and "Jock MacGraw" and "The Gallant Forty Twa".[46]

The second line of Brian McNeill's song "The Baltic tae Byzantium" briefly references the 42nd as "The Gallant Forty Twa".[47]

The traditional Scots Language song "Twa Recruitin' Sergeants" refers to efforts by recruiters to lure Highlanders to the regiment.[48]

Gregory Burke's 2006 play Black Watch for the National Theatre of Scotland, based on interviews with soldiers and featuring as a recurring motif the songs The Gallant Forty Twa and Twa Recruitin' Sergeants, is a dramatised account of the regiment's part in Operation Telic.[49]

Notable soldiers

Battle honours

Battle honours awarded to the regiment were:[50]

- Egypt

- Peninsular War: Corunna, Fuentes D'Onor, Pyrenees, Nivelle, Nive, Orthes, Toulouse, Peninsula

- Waterloo

- Crimean War: Alma, Sevastopol

- Indian Mutiny: Lucknow

- Ashanti Wars: Ashantee 1873-74

- Guadaloupe 1759, Martinique 1762, Havannah (awarded to successor regiment, 1909)

- Busaco, (awarded to successor regiment, 1910)

- North America 1763-64, (awarded to successor regiment, 1914)

- Salamanca, (awarded to successor regiment, 1951)

Victoria Crosses

- Private Walter Cook, Indian Mutiny (15 January 1859)

- Private James Davis, Indian Mutiny (15 April 1858)

- Lieutenant Francis Farquharson, Indian Mutiny (9 March 1858)

- Colour Sergeant William Gardner, Indian Mutiny (5 May 1858)

- Lance-Segeant Samuel McGaw, First Ashanti Expedition (21 January 1874)

- Private Duncan Millar, Indian Mutiny (15 January 1859)

- Quartermaster Sergeant John Simpson, Indian Mutiny (15 April 1858)

- Private Edward Spence, Indian Mutiny (15 April 1858)

- Lance Corporal Alexander Thompson, Indian Mutiny (5 April 1858)

Regimental Colonels

Colonels of the Regiment were:[50]

- 1739–1741: Lt-Gen. John Lindsay, 20th Earl of Crawford

- 1741–1745: Brig-Gen. Hugh Sempill, 12th Lord Sempill

- 1745–1787: Gen. Lord John Murray

- 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot - (1758)

- 1787–1805: Gen. Sir Hector Munro, KB

- 1806–1820: Gen. George Gordon, 5th Duke of Gordon, GCB (Marquess of Huntly)

- 1820–1823: Gen. John Hope, 4th Earl of Hopetoun, GCB

- 1823–1844: Gen. Sir George Murray, GCB, GCH

- 1844–1850: Lt-Gen. Sir John Macdonald, GCB

- 1850–1862: Gen. Sir James Dawes Douglas, GCB

- 1862–1863: F.M. George Hay, 8th Marquess of Tweeddale, KT, GCB

- 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot, The Black Watch - (1861)

- 1863–1881: Gen. Sir Duncan Alexander Cameron, GCB

References

- ^ The Highland regiments that landed in America and took part in the French and Indian War were the 42nd or Royal Highland Regiment ("The Black Watch"), the 77th Regiment of Foot and the 78th Regiment of Foot.

- ^ Pollard 2009, p. 63.

- ^ Cotton, Julian James (1945). List Of Inscriptions On Tombs & Monuments in Madras Vol 1. Madras, British India: Government Press. p. 488. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ Simpson 1996, p. 113.

- ^ Sir K.S.Mackenzie, "General Wade & his Roads", paper before the Inverness Scientific Society,13 April 1897

- ^ Simpson 1996, pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b Simpson 1996, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Simpson 1996, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Groves Lt-Colonel, Percy (1893). History Of The 42nd Royal Highlanders: The Black Watch, Now The First Battalion The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) 1729-1893 (2017 ed.). Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston. pp. 3–4. ISBN 1376269481.

- ^ Groves Lt-Colonel, Percy (1893). History Of The 42nd Royal Highlanders: The Black Watch, Now The First Battalion The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) 1729-1893 (2017 ed.). Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston. p. 4. ISBN 1376269481.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "42nd Royal Highland Regiment". British Empire. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ^ Cannon, p. 34

- ^ Groves Lt-Colonel, Percy (1893). History Of The 42nd Royal Highlanders: The Black Watch, Now The First Battalion The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) 1729-1893 (2017 ed.). Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston. p. 6. ISBN 1376269481.

- ^ Pollard 2009, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Cannon, p. 40

- ^ Groves Lt-Colonel, Percy (1893). History Of The 42nd Royal Highlanders: The Black Watch, Now The First Battalion The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) 1729-1893 (2017 ed.). Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston. p. 6. ISBN 1376269481.

- ^ Groves Lt-Colonel, Percy (1893). History Of The 42nd Royal Highlanders: The Black Watch, Now The First Battalion The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) 1729-1893 (2017 ed.). Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston. p. 6. ISBN 1376269481.

- ^ Cannon, p. 45

- ^ Cannon, p. 46

- ^ "First Highland Regiments in America". Electricscotland.com. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Cannon, p. 49

- ^ Cannon, p. 50

- ^ History of Pittsburgh and environs George Thornton Fleming, American Historical Company, American Historical Society, Incorporated, New York, 1922. "They waited on the commander of the fort, Captain William Murray, who received them politely and introduced them to the Rev. Mr. McLagan, the chaplain of the 42d Highlanders, then the garrison of the fort."

- ^ Cannon, p. 68

- ^ Cannon, p. 73

- ^ Cannon, p. 74

- ^ Cannon, p. 79

- ^ Cannon, p. 80

- ^ Cannon, p. 85

- ^ Stewart, I, p.402-403

- ^ Cannon, p. 118

- ^ Cannon, p. 119

- ^ Cannon, p. 124

- ^ a b Cannon, p. 125

- ^ a b Cannon, p. 126

- ^ a b Cannon, p. 127

- ^ a b Cannon, p. 128

- ^ Cannon, p. 130

- ^ a b Cannon, p. 131

- ^ a b Cannon, p. 132

- ^ Cannon, p. 141

- ^ Dalton, Charles (1904). The Waterloo roll call. With biographical notes and anecdotes. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode. p. 158.

- ^ Cannon, p. 144

- ^ "The Cawnpore Gong". Black Watch. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ "Training Depots". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ "Wha Saw the 42nd". Digital Tradition Mirror. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ "The Baltic tae Byzantium". Musixmatch. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ "Traditional Scottish Songs - Twa Recruitin' Sergeants". www.rampantscotland.com. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ "Black Watch (2006)". National Theatre of Scotland. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ a b "42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot, The Black Watch". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 10 March 2006. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Bibliography

- Cannon, Richard (1845). Historical Record of the Forty-second, or, the Royal Highland Regiment of Foot. London: Parker, Furnivall, and Parker.

- Groves Lt-Colonel, Percy (1893). History Of The 42nd Royal Highlanders: The Black Watch, Now The First Battalion The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) 1729-1893 (2017 ed.). Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston. ISBN 1376269481.

- Pollard, Tony, ed. (2009). Culloden: The History and Archaeology of the Last Clan Battle (1st ed.). Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-020-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - Schofield, Victoria (2012). The Highland Furies: The Black Watch 1739–1899. London: Quercus. ISBN 978-1-84916-918-9.

- Simpson, Peter (1996). The Independent Highland Companies, 1603–1760. Edinburgh: J. Donald. ISBN 978-0-85976-432-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stewart, David (1822). Sketches of the Character, Manners, and Present State of the Highlanders.

- Swinson, Arthur (1972). A Register of the Regiments and Corps of the British Army. London: The Archive Press. ISBN 0-85591-000-3.

External links

- Black Watch

- Archive catalogues for collections relating to soldiers of the 73rd Regiment and 42nd Regiment (The Black Watch), The Black Watch Castle & Museum, Perth, Scotland.

- 1661 establishments in Scotland

- Highland regiments

- Infantry regiments of the British Army

- Military units and formations disestablished in 1881

- Military units and formations established in 1661

- Military units and formations of the United Kingdom in the Peninsular War

- Scottish regiments

- Regiments of the British Army in the Crimean War