Reign of Cleopatra

| Part of a series on |

| Cleopatra VII |

|---|

|

|

|

The reign of Cleopatra VII of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt began with the death of her father, the ruling pharaoh Ptolemy XII Auletes, by March 52 BC. It ended with her death on 10 or 11 August 31 BC.[note 1] Following the reign of Cleopatra, the country of Egypt was transformed into a province of the Roman Empire and the Hellenistic period came to an end.[note 2] During her reign she ruled Egypt and other territories as an absolute monarch, in the tradition of the Ptolemaic dynasty's founder Ptolemy I Soter (r. 305–276 BC) as well as Alexander the Great (r. 336–301 BC) of Macedon, who captured Egypt from the Achaemenid Persian Empire.

Cleopatra and her younger brother Ptolemy XIII acceded to the throne as joint rulers, but a fallout between them led to open civil war. Cleopatra fled briefly to Roman Syria in 48 BC but returned later that year with an army to confront Ptolemy XIII. As a Roman client state, Roman statesman Pompey the Great planned Ptolemaic Egypt as a place of refuge after losing the 48 BC Battle of Pharsalus in Greece against his rival Julius Caesar in Caesar's Civil War. However, Ptolemy XIII had Pompey killed at Pelousion and sent his severed head to Caesar, while the latter occupied Alexandria in pursuit of Pompey. With his authority as consul of the Roman Republic, Caesar attempted to reconcile Ptolemy XIII with Cleopatra. However, Ptolemy XIII's chief adviser Potheinos viewed Caesar's terms as favoring Cleopatra. So his forces, led first by Achillas and then Ganymedes under Arsinoe IV (Cleopatra's younger sister), besieged both Caesar and Cleopatra at the palace. Reinforcements lifted the siege in early 47 BC and Ptolemy XIII died shortly afterwards in the Battle of the Nile. Arsinoe IV was eventually exiled to Ephesus and Caesar, now an elected dictator, declared Cleopatra and her younger brother Ptolemy XIV as joint rulers of Egypt. However, Caesar maintained a private affair with Cleopatra that produced a son, Caesarion (later Ptolemy XV), before he departed Alexandria for Rome.

Cleopatra traveled to Rome as a client queen in 46 and 44 BC, staying at his villa. Following Caesar's assassination in 44 BC Cleopatra attempted to have Caesarion named as his heir. Caesar's grandnephew Octavian (known as Augustus by 27 BC, when he became the first Roman emperor) thwarted this. Cleopatra then had her brother Ptolemy XIV killed and elevated her son Caesarion as co-ruler. In the Liberators' civil war of 43–42 BC, Cleopatra sided with the Roman Second Triumvirate formed by Octavian, Mark Antony, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. She developed a personal relationship with Mark Antony that would eventually produce three children: the twins Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II, and Ptolemy Philadelphus. Antony used his authority as triumvir to carry out the execution of Arsinoe IV at Cleopatra's request. He became increasingly reliant on Cleopatra for both funding and military aid during his invasions of the Parthian Empire and the Kingdom of Armenia. Although his invasion of Parthia was unsuccessful, he managed to occupy Armenia. He brought King Artavasdes II back to Alexandria in 34 BC as a prisoner in his mock Roman triumph hosted by Cleopatra. This was followed by the Donations of Alexandria, in which Cleopatra's children with Antony received various territories under Antony's triumviral authority. Cleopatra was named the Queen of Kings and Caesarion the King of Kings. This event, along with Antony's marriage to Cleopatra and divorce of Octavia Minor, sister of Octavian, marked a turning point that led to the Final War of the Roman Republic.

After engaging in a war of propaganda, Octavian forced Antony's allies in the Roman Senate to flee Rome in 32 BC. He declared war on Cleopatra for unlawfully providing military support to Antony, now a private Roman citizen without public office. Antony and Cleopatra led a joint naval force at the 31 BC Battle of Actium against Octavian's general Agrippa, who won the battle after Cleopatra and Antony fled to the Peloponnese and eventually Egypt. Octavian's forces invaded Egypt in 30 BC. Although Antony and Cleopatra offered military resistance, Octavian defeated their forces, leading to Antony's suicide. When it became clear that Octavian planned to have Cleopatra brought to Rome as a prisoner for his triumphal procession, she also committed suicide, the cause of death reportedly by use of poison. The popular belief is that she was bitten by an asp.

Accession to the throne

Right: Cleopatra dressed as a pharaoh presenting offerings to the goddess Isis, dated 51 BC; limestone stele dedicated by a Greek man named Onnophris; located in the Louvre, Paris

Ptolemy XII Auletes, ruling pharaoh of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, designated in his will that his daughter Cleopatra VII should reign alongside her brother Ptolemy XIII as co-rulers in the moment of his death.[5][6][7][note 3] On 31 May 52 BC Cleopatra was made a regent of Ptolemy XII as indicated by an inscription in the Temple of Hathor at Dendera.[8][9][10][note 4] Duane W. Roller asserts that Ptolemy XII perhaps died sometime before 22 March 51 BC,[11] while Joann Fletcher offers the date 7 March 51 BC.[12] Michael Grant claims it could have occurred as late as May of that year.[13][note 5] Cleopatra's first known act as queen occurred on 22 March 51 BC. She traveled to Hermonthis, near Thebes, to install a new sacred Buchis bull, worshiped as an intermediary for the god Montu in the Ancient Egyptian religion.[11][14][15][note 6] The Roman Senate, which viewed Ptolemaic Egypt as a client state, was not informed of the death of Ptolemy XII until 30 June or 1 August 51 BC. This was most likely an attempt by Cleopatra to suppress this information and consolidate power.[12][13][note 5]

Cleopatra perhaps wedded her brother Ptolemy XIII,[16][note 7] but it is unknown if their marriage ever took place.[14][17] By 29 August 51 BC official documents began listing Cleopatra as the sole ruler, evidence that she had rejected her brother as a co-ruler by this point.[18][19][20] Cleopatra faced several pressing issues and emergencies shortly after taking the throne. These included food shortages and famine caused by drought and low-level flooding of the Nile and assaults by gangs of armed brigands. The lawless behavior instigated by the Gabiniani, the now unemployed, assimilated, and largely Germanic and Gallic Roman soldiers left by Aulus Gabinius to garrison Egypt after restoring Ptolemy XII and removing his daughter Berenice IV from power was also a problem.[21][22] As an astute financial administrator of her kingdom, Cleopatra eventually brought the combined wealth of tax revenues and foreign trade up to 12,000 talents a year, surpassing the wealth creation of some of her Ptolemaic predecessors.[23] In the meantime, however, she inherited her father's debts and owed the Roman Republic 17.5 million drachmas by the time Julius Caesar arrived at Alexandria in 48 BC.[18]

In 50 BC Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, proconsul of Syria, sent his two eldest sons to Egypt. This was most likely to negotiate with the Gabiniani and recruit them as soldiers in the desperate defense of Syria against the Parthians.[26] However, the Gabiniani tortured and murdered them, perhaps with secret encouragement by rogue senior administrators in Cleopatra's court such as the eunuch regent Potheinos. This led her to send the Gabiniani culprits to Bibulus as prisoners awaiting his judgment.[26][19] Although a seemingly shrewd act by the young queen, Bibulus sent the prisoners back to her and chastised her for interfering in Roman affairs that should have been handled directly by the Roman Senate.[27] Bibulus, siding with Pompey the Great in Caesar's Civil War, was then charged with preventing Caesar from landing a naval fleet in Greece. He failed at the task which ultimately allowed Julius Caesar to reach Egypt in pursuit of Pompey.[27]

Although Cleopatra had rejected her 11-year-old brother as a joint ruler in 51 BC, Ptolemy XIII still retained strong allies, notably Potheinos, his tutor and administrator of his properties. The Romans, including Caesar, initially viewed him as the power behind the throne.[28][29][30] Others involved in the cabal against Cleopatra included Achillas, a prominent military commander, and Theodotus of Chios, another tutor of Ptolemy XIII.[28][31] Cleopatra seems to have attempted a short-lived alliance with her brother Ptolemy XIV, but by the autumn of 50 BC Ptolemy XIII had the upper hand in their conflict and began signing documents with his name before that of his sister, followed by the establishment of his first regnal date in 49 BC.[14][32][33][note 8]

Assassination of Pompey

Cleopatra and her forces were still holding their ground against Ptolemy XIII within Alexandria when Gnaeus Pompeius, son of Pompey, arrived at Alexandria in the summer of 49 BC seeking military aid on behalf of his father.[32] After returning to Italy from the wars in Gaul and crossing the Rubicon in January of 49 BC, Caesar forced Pompey and his supporters to flee to Greece in a Roman civil war.[34][35] In perhaps their last joint decree, both Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII agreed to Gnaeus Pompeius' request. They sent his father 60 ships and 500 troops, including the Gabiniani, a move that helped erase some of the debt owed to Rome by the Ptolemies.[34][36] The Roman writer Lucan claims that by early 48 BC Pompey named Ptolemy XIII as the legitimate sole ruler of Egypt; whether true or not Cleopatra was forced to flee Alexandria and withdraw to the region of Thebes.[37][38][39] However, by the spring of 48 BC Cleopatra traveled to Syria with her younger sister Arsinoe IV to gather an invasion force that would head to Egypt.[40][33][41] She returned with an army, perhaps right around the time of Caesar's arrival, but her brother's forces, including some Gabiniani mobilized to fight against her. They blocked her advance to Alexandria, and she had to make camp outside Pelousion in the eastern Nile Delta.[42][33]

In Greece, Caesar and Pompey's forces engaged each other at the decisive Battle of Pharsalus on 9 August 48 BC, leading to the destruction of most of Pompey's army and his forced flight to Tyre, Lebanon.[42][43][44][note 9] Given his close relationship with the Ptolemies, he ultimately decided that Egypt would be his place of refuge, where he could replenish his forces.[45][44][46] Ptolemy XIII's advisers, however, feared the idea of Pompey using Egypt as his base of power in a protracted Roman civil war.[45][47][48] They also wanted to ensure that none of the Gabiniani would leave their campaign against Cleopatra to join Pompey's forces instead.[47] In a scheme devised by Theodotos, Pompey arrived by ship near Pelousion after being invited by written message, only to be ambushed and stabbed to death on 28 September 48 BC.[45][43][49][note 10] Ptolemy XIII believed he had demonstrated his power and simultaneously defused the situation by having Pompey's severed head sent to Caesar, who arrived in Alexandria by early October and resided at the royal palace.[50][51][52][note 10] Theodotos presented Caesar with his son-in-law Pompey's embalmed head, which Caesar retrieved and planned to bury properly along the shores of Alexandria.[53] Caesar expressed grief and outrage over the killing of Pompey, and called on both Ptolemy XIII and Cleopatra VII to disband their forces and reconcile.[50][54][52][note 11]

Relationship with Julius Caesar

Caesar's request for partial repayment of the 17.5 million drachmas owed to Rome (to pay for immediate military expenditures) was met with a response by Potheinos. He replied that it would be made later if Caesar would leave Alexandria, but this offer was rejected.[60][61][62] Ptolemy XIII arrived at Alexandria at the head of his army, in clear defiance of Caesar's demand that he disband and leave his army before his arrival.[60][62] Cleopatra initially sent emissaries to Caesar, but upon allegedly hearing that Caesar was inclined to having affairs with royal women, she came to Alexandria to see him personally.[60][61][62] Historian Cassius Dio records that she simply did so without informing her brother, dressing in an attractive manner and charming Caesar with her wit and linguistic skills.[60][63][64] Plutarch provides an entirely different and perhaps mythical account that alleges she was bound inside a bed sack to be smuggled into the palace to meet Caesar.[60][59][65][note 12]

When Ptolemy XIII realized that his sister was in the palace consorting directly with Caesar instead of at Pelousion, he attempted to rouse the populace of Alexandria into a riot. Caesar arrested him then used his oratorical skills to calm the frenzied crowd gathered outside the palace.[66][67][68] Caesar then brought Cleopatra VII and Ptolemy XIII before the assembly of Alexandria. Here he revealed the written will of Ptolemy XII—previously possessed by Pompey—naming Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII as his joint heirs.[69][67][61][note 13] Caesar then attempted to arrange for the other two siblings, Arsinoe IV and Ptolemy XIV, to rule together over Cyprus, thus removing potential rival claimants to the Egyptian throne. This would also appease the Ptolemaic subjects still bitter over the loss of Cyprus to the Romans in 58 BC.[70][67][71]

Potheinos, judged that this agreement actually favored Cleopatra over Ptolemy XIII and that the latter's army of 20,000, including the Gabiniani, could most likely defeat Caesar's army of 4,000 unsupported troops. He decided to have Achillas lead their forces to Alexandria to attack both Caesar and Cleopatra.[70][67][72][note 14] The resulting siege of the palace with Caesar and Cleopatra trapped inside lasted into the following year of 47 BC. It included Caesar's burning of ships in the harbor that spread fires and potentially burned down part of the Library of Alexandria.[73][54][74][note 15] Caesar managed to execute Potheinos after he attempted an assassination plot against him.[75] Arsinoe IV joined forces with Achillas and was declared queen. Soon afterwards, she had her tutor Ganymedes kill Achillas and take his position as commander of her army.[76][77][78][note 16] Ganymedes then tricked Caesar into requesting the presence of his erstwhile captive Ptolemy XIII as a negotiator, only to have him join the army of Arsinoe IV.[76][79][80] With his detailed knowledge of the palace, Ganymedes pumped seawater into the reservoirs via water pipes, but Cleopatra and Caesar countered this by ordering the construction of fresh water wells.[80][81]

Sometime between January and March 47 BC Caesar's reinforcements arrived. These included soldiers led by Mithridates of Pergamon and Antipater the Idumaean, who would receive Roman citizenship for his timely aid (a status that would be inherited by his son Herod the Great).[76][54][83][note 17] Ptolemy XIII and Arsinoe IV withdrew their forces to the Nile River, where Caesar attacked them and forced Ptolemy XIII to flee by boat. It capsized, and he drowned. His body was later found nearby in the mud.[84][54][85][note 18] Ganymedes was perhaps killed in the battle. Theodotos was found years later in Asia by Marcus Brutus and executed. Arsinoe IV was forcefully paraded in Caesar's triumph in Rome before being exiled to the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus.[86][87][88] Cleopatra was conspicuously absent from these events and resided in the palace, most likely because she was pregnant with Caesar's child (perhaps since September 47 BC). She gave birth to Caesarion on 23 June 47 BC.[89][90][91] Caesar and Cleopatra likely visited the Tomb of Alexander the Great together.[91] Caesar also ensured the proper burial of Pompey's embalmed head in a tomb near the eastern wall of Alexandria.[92]

Caesar's term as consul had expired at the end of 48 BC.[86] However, his officer Mark Antony, recently returned to Rome from the battle at Pharsalus, helped to secure Caesar's election as dictator. This lasted for a year, until October 47 BC, providing Caesar with the legal authority to settle the dynastic dispute in Egypt.[86] Wary of repeating the mistake of Berenice IV in having a sole-ruling female monarch, Caesar appointed 12-year-old Ptolemy XIV as 22-year-old Cleopatra VII's joint ruler in a nominal sibling marriage, but Cleopatra continued living privately with Caesar.[93][54][83][note 19] The exact date at which Cyprus was returned to her control is not known, although she had a governor there by 42 BC.[94][83]

Before returning to Rome to attend to urgent political matters, Caesar is alleged to have joined Cleopatra for a cruise of the Nile and sightseeing of monuments, although this may be a romantic tale reflecting later well-to-do Roman proclivities and not a real historic event.[95][54][96][note 20] The historian Suetonius provided considerable details about the voyage, including use of a Thalamegos pleasure barge. First constructed by Ptolemy IV during his reign, it measured 300 ft (91 m) in length and 80 ft (24 m) in height and was complete with dining rooms, state rooms, holy shrines, and promenades along its two decks resembling a floating villa.[95][97] Cleopatra allegedly used the Thalamegos again years later to sail to Mark Antony's provisional headquarters at Tarsos.[98] Its design almost certainly had an influence on the later Roman Nemi ships.[99] Caesar could have been interested in a Nile cruise owing to his fascination with geography. He was well-read in the works of Eratosthenes and Pytheas, and perhaps wanted to discover the source of the river, but his troops reportedly demanded they turn back after nearly reaching Ethiopia.[100][101]

Caesar departed from Egypt in about April 47 BC.[102] The reason for his departure was said to be that Pharnaces II of Pontus, son of Mithridates the Great, was stirring up trouble for Rome in Anatolia and needed to be confronted. It is possible, however, that Caesar, married to the prominent Roman woman Calpurnia, wanted to avoid being seen together with Cleopatra when she bore him their son.[102][96] He left three legions in Egypt, later increased to four, under the command of the freedman Rufio, to secure Cleopatra's tenuous position but also perhaps to keep her activities in check.[102][103][104]

Cleopatra's alleged child with Caesar was born 23 June 47 BC, as preserved on a stele at the Serapeion in Memphis.[105][54][106][note 21] In the stele he was named "Pharaoh Caesar", but the Alexandrians preferred the patronymic Caesarion.[107][108][54] Perhaps owing to his still childless marriage with Calpurnia, Caesar remained silent about Caesarion. There is conflicting evidence that he publicly denied fathering him but privately accepted him as his son.[109][note 22] Cleopatra, on the other hand, made repeated official declarations about Caesarion's parentage, with Caesar as the father.[109][110] She also built a Caesareum temple near the harbor of Alexandria dedicated to his worship.[103][111]

Right image: the Esquiline Venus, a Roman or Hellenistic-Egyptian statue of Venus (Aphrodite), which is most likely a depiction of Cleopatra,[113] Capitoline Museums, Rome

Cleopatra VII and her nominal joint ruler Ptolemy XIV visited Rome sometime in late 46 BC, presumably without Caesarion. They were given lodging in Caesar's Villa within the Horti Caesaris.[114][115][116][note 23] Like he did with their father Ptolemy XII, Julius Caesar awarded both Cleopatra VII and Ptolemy XIV with the legal status of 'friend and ally of the Roman people' (Latin: socius et amicus populi Romani), in effect client rulers loyal to Rome.[117][115][118] Cleopatra's distinguished visitors at Caesar's villa across the Tiber included the senator Cicero. He was not flattered by her and found her to be arrogant, especially after one of her advisers failed to provide him with requested books from the Library of Alexandria.[119][120] Sosigenes of Alexandria, one of the members of Cleopatra's court, aided Caesar in the calculations for the new Julian Calendar, put into effect 1 January 45 BC.[121][122][123] The Temple of Venus Genetrix, established in the Forum of Caesar on 25 September 46 BC, contained a golden statue of Cleopatra (which still stood there during the 3rd century AD), associating the mother of Caesar's child directly with the goddess Venus, mother of the Romans.[124][122][125] The statue also subtly linked the Egyptian goddess Isis with the Roman religion. Caesar may have had plans to build a temple to Isis in Rome, as was voted by the Senate a year after his death.[119]

Fletcher asserts that it is unclear if Cleopatra consistently stayed in Rome until 44 BC or briefly returned to Egypt after Caesar traveled to Roman Spain in November 46 BC to wage war against the sons of Pompey.[126] Since Cleopatra was also present in the city in 44 BC during Caesar's assassination, it is unclear if this represented a single, two-year-long trip to Rome or two separate visits. The latter is more likely according to Roller.[127] Cleopatra's presence in Rome most likely had an effect on the events at the Lupercalia festival a month before Caesar's assassination.[128][129] Mark Antony attempted to place a royal diadem on Caesar's head, which he refused. This was most likely a staged performance, perhaps to gauge the Roman public's mood about accepting Hellenistic-style kingship.[128][129] Cicero, who was present at the festival, mockingly asked where the diadem came from, an obvious reference to the Ptolemaic queen who he abhorred.[128][129]

Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March (15 March 44 BC), but Cleopatra stayed in Rome until about mid-April, in the vain hope of having Caesarion recognized as Caesar's heir.[130][131][132] However, Caesar's will named his grandnephew Octavian as the primary heir. He arrived in Italy around the same time Cleopatra decided to depart for Egypt.[130][131][133] A few months later Cleopatra decided to kill Ptolemy XIV by poisoning, elevating her son Caesarion instead as her co-ruler.[134][135][136]

Cleopatra in the Liberators' civil war

Octavian, Mark Antony, and Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate in 43 BC. They were each elected for five-year terms to restore order to the Republic and bring Caesar's assassins to justice.[138][139] Cleopatra received messages from both Gaius Cassius Longinus, one of Caesar's assassins, and Publius Cornelius Dolabella, proconsul of Syria and a Caesarian loyalist, requesting military aid.[138] She decided to write Cassius an excuse that her kingdom faced too many internal problems, while sending the four legions left by Caesar in Egypt to Dolabella.[138][140] However, Cassius captured these troops in Palestine, while they traveled en route to Syria.[138][140] Serapion, Cleopatra's governor of Cyprus, defected to Cassius and provided him with ships. Cleopatra took her own fleet to Greece to personally assist Octavian and Antony. Her ships were heavily damaged in a Mediterranean storm, however, and she arrived too late to aid in the fighting.[138][141] By the autumn of 42 BC Antony had defeated the forces of Caesar's assassins at the Battle of Philippi in Greece, leading to the suicides of Cassius and Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger.[138][142]

By the end of 42 BC, Octavian gained control over much of the western half of the Roman Republic and Antony the eastern half, with Lepidus largely marginalized.[143] Antony moved his headquarters from Athens to Tarsos in Anatolia by the summer of 41 BC.[143][144] He summoned Cleopatra to Tarsos in several letters, invitations she initially rebuffed until he sent his envoy Quintus Dellius to Alexandria, convincing her to come.[145][146] The meeting would allow Cleopatra to clear up the misconception that she seemed to support Cassius during the civil war, and would address pressing issues about territorial exchanges in the Levant. Mark Antony also undoubtedly desired to form a personal, romantic relationship with the queen.[147][146]

Cleopatra sailed up the Kydnos River to Tarsos in her Thalamegos, inviting Antony and his officers for two nights of lavish banquets on board her ship. Antony attempted to return the favor on the third night of dining with his own far less luxurious banquet.[148][144] Cleopatra presented herself as the Egyptian goddess Isis in the appearance of the Greek goddess Aphrodite, meeting her divine husband Osiris in the form of the Greek god Dionysus, the latter whom the priests of Artemis at Ephesus had associated with Antony prior to this meeting with Cleopatra.[144] Some surviving coins of Cleopatra also depict her as Venus–Aphrodite.[149] Cleopatra managed to clear her name as a supposed supporter of Cassius, arguing she had really attempted to help Dolabella in Syria. At the same time she convinced Antony to have her rival sister Arsinoe IV dragged from her place of exile at the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus and executed.[150][151] Her former governor of Cyprus Serapion, who had rebelled against her and joined Cassius, was found at Tyre and handed over to Cleopatra.[150][152]

Relationship with Mark Antony

Cleopatra invited Antony to come to Egypt before departing from Tarsos, which led Antony to visit Alexandria by November 41 BC.[150][153] He was well received by the populace of Alexandria for his heroic actions in restoring Ptolemy XII to power and, unlike Caesar, coming to Egypt without an occupational force.[154][155] In Egypt, Antony continued to enjoy the lavish royal lifestyle he had witnessed aboard Cleopatra's ship docked at Tarsos.[156][152] He also had his subordinates, such as Publius Ventidius Bassus, drive the Parthians out of Anatolia and Syria.[157][158][159][note 24]

Of all the queens of antiquity, those who ruled independently at times were married for most of their careers.[160] Cleopatra, however, reigned for most of her 21 years as a sole monarch, with nominal joint rulers and a possible marriage to Antony very late in her life.[160] Having Caesarion as her sole heir produced both benefits and dangers. His sudden death could extinguish the dynasty, but rivalry with other potential heirs and siblings could also spell his downfall.[160] Cleopatra carefully chose Antony as her partner to produce further heirs, as he was deemed to be the most powerful Roman figure following Caesar's demise.[161] With his triumviral powers, Antony also had the broad authority to restore former Ptolemaic lands to Cleopatra now in Roman hands.[162][163] While it is clear that Cleopatra controlled both Cilicia and Cyprus by 19 November 38 BC with a mention of her governor Diogenes who administered both, the transfer probably occurred earlier in the winter of 41–40 BC, during her time spent with Antony.[162] Plutarch asserted that Cleopatra played dice, drank alcohol, hunted wild game, and attended military exercises with Antony. These masculine activities did not endear her to later Roman authors, but they demonstrated the close relationship she fostered with her Roman partner.[164]

By the spring of 40 BC, troubles in Syria forced Mark Antony to end his vacation in Egypt with Cleopatra. His governor Lucius Decidius Saxa had been killed and his army taken by Quintus Labienus, a former officer under Cassius who now served the Parthian Empire.[165] Cleopatra provided Antony with 200 ships for his campaign and as payment for her newly acquired territories.[165] She would not see him again until 37 BC, but she maintained correspondence and evidence suggests she kept a spy in his camp.[165] By the end of 40 BC Cleopatra gave birth to twins, a boy named Alexander Helios and a girl named Cleopatra Selene II, both of whom Antony acknowledged as his children.[166][167] Helios (Greek: Ἥλιος), the sun, and Selene (Greek: Σελήνη), the moon, were symbolic of a new era of societal rejuvenation,[168] as well as sign that Cleopatra hoped Antony would repeat the exploits of Alexander the Great by conquering Persia.[155]

Events of the Perusine War (41–40 BC) disrupted Mark Antony's focus on confronting the Parthians in the east. The war was initiated by his ambitious wife Fulvia against Octavian in the hopes of making her husband the undisputed leader of Rome.[168][172] Although it has been suggested that part of her motivation was to cleave Antony from Cleopatra, this is unlikely, as the conflict emerged in Italy even before Cleopatra's meeting with Antony at Tarsos.[173] Fulvia and Antony's brother Lucius Antonius were eventually besieged by Octavian at Perusia (modern Perugia, Italy) and then exiled from Italy. Fulvia died after this at Sikyon in Greece while attempting to reach Antony.[174] Her sudden death led to a reconciliation of Octavian and Antony at Brundisium in Italy in September 40 BC.[174][155] Although the agreement struck at Brundisium solidified Antony's control of the Roman Republic's territories east of the Ionian Sea, it also stipulated that he concede Italia, Hispania, and Gaul, and marry Octavian's sister Octavia the Younger, a potential rival for Cleopatra.[175][176]

In December 40 BC Cleopatra received Herod I (the Great) in Alexandria as an unexpected guest and refugee who fled a turbulent situation in Judea.[177] Mark Antony had established Herod there as a tetrarch, but he was soon at odds with Antigonus II Mattathias of the long-established Hasmonean dynasty.[177] Antigonus had imprisoned Herod's brother and fellow tetrarch Phasael, who was executed while Herod was in mid-flight towards Cleopatra's court.[177] Cleopatra attempted to provide him with a military assignment, but Herod declined and traveled to Rome, where the triumvirs Octavian and Mark Antony named him king of Judea.[178][179] This act put Herod on a collision course with Cleopatra, who wished to reclaim former Ptolemaic territories of his new Herodian kingdom.[178]

Relations between Mark Antony and Cleopatra perhaps soured when he not only married Octavia, but having moved his headquarters to Athens also sired her two children, Antonia the Elder in 39 BC and Antonia Minor in 36 BC.[180] However, Cleopatra's position in Egypt was secure.[155] Her rival Herod was occupied with civil war in Judea that required heavy Roman military assistance, but received none from Cleopatra.[180] Since the triumviral authority of Mark Antony and Octavian had expired on 1 January 37 BC, Octavia arranged for a meeting at Tarentum where the triumvirate was officially extended to 33 BC.[181] With two legions granted by Octavian and a thousand soldiers lent by Octavia, Mark Antony traveled to Antioch, where he made preparations for war against the Parthians.[182]

Antony summoned Cleopatra to Antioch to discuss pressing issues such as Herod's kingdom and financial support for his Parthian campaign.[182][183] Cleopatra brought her three-year-old twins to Antioch, where Mark Antony saw them for the first time. They probably first received their surnames Helios and Selene here as part of Antony and Cleopatra's ambitious plans for the future.[184][185] In order to stabilize the east, Antony not only enlarged Cleopatra's domain[183] but also established new ruling dynasties and client rulers who would be loyal to him yet would ultimately outlast him.[163] These included Herod I of Judea, Amyntas of Galatia, Polemon I of Pontus and Archelaus of Cappadocia.[186]

In this arrangement Cleopatra gained significant former Ptolemaic territories in the Levant. This included nearly all of Phoenicia (centered in what is now modern Lebanon) minus Tyre and Sidon, which remained in Roman hands.[188][163][183] She also received Ptolemais Akko (modern Acre, Israel), a city that Ptolemy II established.[188] Given her ancestral relations with the Seleucids, Antony granted her the region of Koile-Syria along the upper Orontes River.[189][183] She was even given the region surrounding Jericho in Palestine, but she leased this territory back to Herod.[190][179] At the expense of the Nabataean king Malichus I (a cousin of Herod), Cleopatra was also given a portion of the Nabataean Kingdom around the Gulf of Aqaba on the Red Sea, including Ailana (modern Aqaba, Jordan).[191][179] To the west Cleopatra was handed Cyrene along the Libyan coast, as well as Itanos and Olous in Roman Crete. This restored much of the territory lost by the Ptolemies, but did not include any territories in the Aegean Sea or southwest Asia Minor.[192][183] Cleopatra's control over much of these new territories was nominal, and they were still administered by Roman officials. Nevertheless, they enriched her kingdom and led her to declare the inauguration of a new era by double-dating her coinage in 36 BC.[193][194]

Antony's rival Octavian exploited the enlargement of the Ptolemaic realm by relinquishing directly controlled Roman territory. Octavian tapped into public sentiment in Rome against the empowerment of a foreign queen at the expense of their Republic.[195] Octavian also fostered the narrative that Antony was neglecting his virtuous Roman wife Octavia. He granted her and his wife Livia the extraordinary privileges of sacrosanctity.[195] Cornelia Africana, daughter of Scipio Africanus, mother of the reformists Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, and love interest of Cleopatra's great-grandfather Ptolemy VIII, was the first living Roman woman to have a statue dedicated in her honor.[193] She was followed by Octavian's sister Octavia and his wife Livia, whose statues were most likely erected in the Forum of Caesar to rival that of Cleopatra's statue erected there earlier by Julius Caesar.[193]

In 36 BC, Cleopatra accompanied Antony to the Euphrates River, perhaps as far as Seleucia at the Zeugma, on the first leg of his journey to invade the Parthian Empire.[196] She then toured of some of her newly acquired territories. She traveled past Damascus and entered the lands of Herod, who escorted her in lavish conditions back to the Egyptian border town of Pelousion.[197] Her main reason for returning to Egypt was her advanced state of pregnancy. By the summer of 36 BC she gave birth to Ptolemy Philadelphus, her second son with Antony.[197][183] He was also named after the second monarch of the Ptolemaic dynasty in what Cleopatra almost certainly intended as a prophetic gesture that the Ptolemaic Kingdom would be restored to its former glory.[197][179]

Antony's Parthian campaign in 36 BC turned into a complete debacle having been stymied by a number of factors such as extreme weather, the spread of disease, and the betrayal of Artavasdes II of Armenia, who defected to the Parthian side.[198][163][199] After losing some 30,000 men, more so than Crassus at Carrhae (an indignity he had hoped to avenge), Antony finally arrived at Leukokome near Berytus (modern Beirut, Lebanon) in December. He engaged in heavy drinking before Cleopatra arrived to provide funds and clothing for his battered troops.[198][200] Octavia offered to lend him more troops for another expedition. Antony wished to avoid the political pitfalls of returning to Rome, however, so traveled with Cleopatra back to Alexandria to see his newborn son.[198]

Donations of Alexandria

Antony prepared for another Parthian expedition in 35 BC, this time aimed at their ally Armenia. As he did so Octavia traveled to Athens with 2,000 troops in alleged support of Antony. This was most likely a scheme devised by Octavian to embarrass Antony for his military losses.[203][204][note 26] Antony received the troops and told Octavia not to stray east of Athens. He and Cleopatra traveled together to Antioch, only to suddenly and inexplicably abandon the military campaign and head back to Alexandria.[203][204] When Octavia returned to Rome Octavian portrayed his sister as a victim wronged by Antony. She refused to leave Antony's household, however, and return to Octavian's in Rome.[205][163] Octavian's confidence grew as he eliminated his rivals in the west. These included Sextus Pompeius and even Lepidus, the third member of the triumvirate, who was placed under house arrest after revolting against Octavian in Sicily.[205][163][200]

Antony sent Quintus Dellius as his envoy to Artavasdes II of Armenia in 34 BC to negotiate a potential marriage alliance between the Armenian king's daughter and Antony and Cleopatra's son Alexander Helios.[206][207] When this was declined, Antony marched his army into Armenia, defeated its forces and captured the king and the Armenian royal family.[206][208] They were sent back to Alexandria as prisoners in golden chains befitting their royal status.[206][207] Antony then held a military parade in Alexandria mocking a Roman triumph. He dressed as Dionysos and rode into the city on a chariot presenting the royal prisoners to Queen Cleopatra, who sat on a golden throne above a silver dais.[206][209] News of this event was heavily criticized in Rome as being distasteful, if not a perversion of time-honored Roman rites and rituals to be enjoyed instead by an Egyptian queen and her subjects.[206]

In an event held at the gymnasium soon after the triumph, known as the Donations of Alexandria, Cleopatra dressed as Isis and declared that she was the Queen of Kings with her son Caesarion, King of Kings. She declared Alexander Helios, dressed as a Median, king of Armenia, Medes, and Parthia, and two-year-old Ptolemy Philadelphos, dressed as a Macedonian-Greek ruler, king of Syria and Cilicia.[214][215][216] Cleopatra Selene was also bestowed with Crete and Cyrene.[217][218] Given the polemic, contradictory, and fragmentary nature of primary sources from the period, it is uncertain if Cleopatra and Antony were also formally wed at this ceremony or if they had any marriage at all.[217][216][note 29] However, coins of Antony and Cleopatra depict them in the typical manner of a Hellenistic royal couple.[217] Antony then sent a report to Rome requesting ratification of these territorial claims, which Octavian wanted to publicize for propaganda purposes, but the two consuls, both supporters of Antony, had it censored from public view.[219][218]

In late 34 BC, following the Donations of Alexandria, Antony and Octavian engaged in a heated war of propaganda that would last for years.[220][218] Antony claimed that his rival had illegally deposed Lepidus from their triumvirate and barred him from raising troops in Italy. Octavian accused Antony of unlawfully detaining the king of Armenia, marrying Cleopatra despite still being married to his sister Octavia, and wrongfully claiming Caesarion as the heir of Caesar instead of Octavian.[220][218] The litany of accusations and gossip associated with this propaganda war have shaped popular perceptions of Cleopatra from Augustan-period literature to various media in modern times.[221][222]

Aside from casual criticisms of Cleopatra's extravagant lifestyle and corruption of simple Antony with her opulence, she was also said by some Roman authors to have resorted to witchcraft as a lethal sorceress. She not only toyed with the idea of poisoning many, Antony included, but also intended to conquer and punish Rome itself. She a woman as dangerous as Homer's Helen of Troy in toppling the order of civilization.[225] Antony was generally viewed as having lost his judgment, brainwashed by Cleopatra's magic spells.[226] Antony's supporters rebutted with tales of Octavian's wild and promiscuous sex life, while graffiti now often appeared slandering either side as being sexually obscene.[226] Cleopatra had a conveniently timed Sibylline oracle claim that Rome would be punished but that peace and reconciliation would follow in a golden age led by the queen.[227] In an account of Lucius Munatius Plancus, preserved in Horace's Satires, Cleopatra was said to have made a bet that she could spend 2.5 million drachmas in a single evening. She proved it by removing a pearl, one of the most expensive known, from one of her earrings and dissolving it in vinegar at her dinner party.[228] The accusation that Antony had stolen the books of the Library of Pergamon to restock the Library of Alexandria, however, was an admitted fabrication by Gaius Calvisius Sabinus. He may have been the source of many other slanders of Antony in support of Octavian's side.[229]

A papyrus document dated to February 33 BC contains with little doubt the signature handwriting of Cleopatra VII.[223][224] It concerns certain tax exemptions in Egypt granted to Publius Canidius Crassus (or Quintus Caecillius),[note 30] former Roman consul and Antony's confidant who would command his land forces at Actium.[230][224] A subscript in a different handwriting at the bottom of the papyrus reads "make it happen" (Greek: γινέσθωι, romanized: ginesthō), undoubtedly the autograph of the queen, as it was Ptolemaic practice to countersign documents to avoid forgery.[230][224]

Battle of Actium

In a speech to the Roman Senate on the first day of his consulship on 1 January 33 BC, Octavian accused Antony of attempting to subvert Roman freedoms and authority as a slave to his Oriental queen, who he said was given lands that rightfully belonged to the Romans.[231] Before Antony and Octavian's joint imperium expired on 31 December 33 BC, Antony declared Caesarion as the true heir of Julius Caesar in an attempt to undermine Octavian.[231] On 1 January 32 BC the Antonian loyalists Gaius Sosius and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus were elected as consuls.[230] On 1 February 32 BC Sosius gave a fiery speech condemning Octavian, now a private citizen without public office, introducing pieces of legislation against him.[230][232] During the next senatorial session, Octavian entered the Senate house with armed guards and levied his own accusations against the consuls.[230][233] Intimidated by this act, the next day the consuls and over two-hundred senators still in support of Antony fled Rome and joined his side. Antony established his own counter Roman Senate.[230][233][234] Although he held military office and his reputation was still largely intact, Antony was still fundamentally reliant on Cleopatra for military support.[230] The couple traveled together to Ephesus in 32 BC, where Cleopatra provided him with 200 naval ships of the 800 total he was able to acquire.[230]

Domitius Ahenobarbus, wary of having Octavian's propaganda confirmed to the public, attempted to persuade Antony to have Cleopatra excluded entirely from the military efforts launched against Octavian.[235][236] Publius Canidius Crassus made the counterargument that Cleopatra was funding the war effort and, as a long-reigning monarch, was by no means inferior to the male allied kings Antony had summoned for the campaign.[235][236] Cleopatra refused Antony's requests that she return to Egypt, judging that by blocking Octavian in Greece she could defend Egypt more easily from him.[235][236] Cleopatra's insistence that she be involved in the battle for Greece led to defections of prominent Romans such as Domitius Ahenobarbus and Lucius Munatius Plancus.[235][233]

During the spring of 32 BC Antony and Cleopatra traveled to Samos and then Athens, where Cleopatra was reportedly well received.[235] She persuaded Antony to send Octavia an official declaration of divorce.[235][233][216] This encouraged Munatius Plancus to advise Octavian that he should seize Antony's will, invested with the Vestal Virgins.[235][233][218] Although a violation of sacred customs and legal rights, Octavian forcefully acquired the document from the Temple of Vesta. It was a useful tool in the propaganda war against Antony and Cleopatra.[235][218] In the selective public reading of the will, Octavian highlighted the claim that Caesarion was heir to Caesar, that the Donations of Alexandria were legal, that Antony should be buried alongside Cleopatra in Egypt instead of Rome, and that Alexandria would be made the new capital of the Roman Republic.[237][233][218] In a show of loyalty to Rome, Octavian decided to begin construction of his own mausoleum at the Campus Martius.[233] His legal standing was also improved by being elected consul in 31 BC, reentering public office.[233] With Antony's will made public, Octavian had his casus belli and Rome declared war on Cleopatra,[237][238][239] not Antony.[note 31] The legal argument for war was based less on Cleopatra's territorial acquisitions, with former Roman territories ruled by her children with Antony, and more on the fact that she was providing military support to a private citizen now that Antony's triumviral authority had expired.[240] Octavian's wish to invade Egypt also coincided with his financial concern of collecting the massive debts owed to Caesar by Cleopatra's father Ptolemy XII. These were passed on to Cleopatra and were now the prerogative of Octavian, Caesar's heir.[241]

Antony and Cleopatra had greater numbers of troops (i.e. 100,000 men) and ships (i.e. 800 vessels) than Octavian, who reportedly had 200 ships and 80,000 men.[242][236] However, the crews of Antony and Cleopatra's navy were not all well-trained, some of them perhaps from merchant vessels, whereas Octavian had a fully professional force.[243] Antony wanted to cross the Adriatic Sea and blockade Octavian at either Tarentum or Brundisium,[244] but Cleopatra, concerned primarily with defending Egypt, overrode the decision to attack Italy directly.[242][236] Antony and Cleopatra set up their winter headquarters at Patrai in Greece and by the spring of 31 BC they moved to Actium along the southern Ambracian Gulf.[242][244] With this position Cleopatra had the defense of Egypt in mind, as any southward movement by Octavian's fleet along the coast of Greece could be detected.[242]

Cleopatra and Antony had the support of various allied kings. Conflict between Cleopatra and Herod had previously erupted and an earthquake in Judea provided an excuse for him and his forces not to be present at Actium in support of the couple.[245] They also lost the support of Malichus I of Nabataea, which would prove to have strategic consequences.[246] Antony and Cleopatra lost several skirmishes against Octavian around Actium during the summer of 31 BC. Defections to Octavian's camp continued, including Antony's long-time companion Quintus Dellius.[246] The allied kings also began to defect to Octavian's side, starting with Amyntas of Galatia and Deiotaros of Paphlagonia.[246] While some in Antony's camp suggested abandoning the naval conflict to retreat inland and face Octavian in the Greek interior, Cleopatra urged for a naval confrontation to keep Octavian's fleet away from Egypt.[247]

On 2 September 31 BC the naval forces of Octavian, led by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, met those of Antony and Cleopatra for a decisive engagement, the Battle of Actium.[247][244][238] On board her flagship the Antonias, Cleopatra commanded 60 ships at the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf, at the rear of the fleet. This was likely a move by Antony's officers to marginalize her during the battle.[247] Antony had ordered that their ships have sails on board for a better chance to pursue or flee from the enemy. Cleopatra, ever-concerned about defending Egypt, used them to move swiftly through the area of major combat in a strategic withdrawal to the Peloponnese.[250][251][252] Burstein writes that partisan Roman writers would later accuse Cleopatra of cowardly deserting Antony, but their original intention of keeping their sails on board may have been to break the blockade and salvage as much of their fleet as possible.[252] Antony followed her and boarded her ship, identified by its distinctive purple sails, as the two escaped the battle and headed for Tainaron.[250] Antony reportedly avoided Cleopatra during this three-day voyage, until her ladies in waiting at Tainaron urged him to speak with her.[253] The Battle of Actium raged on without Cleopatra and Antony, until the morning of 3 September, when there were massive defections of both officers, troops, and even allied kings to Octavian's side.[253][251][254]

Downfall and death

While Octavian occupied Athens, Antony and Cleopatra landed at Paraitonion in Egypt.[253][256] The couple went their separate ways. Antony went to Cyrene to raise more troops. Cleopatra sailed into the harbor at Alexandria in a misleading attempt to portray the activities in Greece as a victory.[253] Conflicting reports make it unclear if Cleopatra had financial difficulties at this juncture or not. Some claims, such as robbing temples of their wealth to pay for her military expenditures, were likely Augustan propaganda.[257] It is also uncertain if she actually executed Artavasdes II of Armenia and sent his head to his rival Artavasdes I, king of Media Atropatene, in an attempt to strike an alliance with him.[258][259]

Lucius Pinarius, Mark Antony's appointed governor of Cyrene, received word that Octavian had won the Battle of Actium before Antony's messengers could arrive at his court.[258] Pinarius had these messengers executed and defected to Octavian's side, surrendering to him the four legions under his command that Antony wanted to obtain.[258] Antony nearly committed suicide after this news but his staff officers stopped him.[258] In Alexandria he built a reclusive cottage on the island of Pharos. He nicknamed it the Timoneion, after the philosopher Timon of Athens, who was famous for his cynicism and misanthropy.[258] Herod the Great, who had personally advised Antony after the Battle of Actium that he should betray Cleopatra, traveled to Rhodes to meet Octavian and resign his kingship out of loyalty to Antony.[260] Impressed by his speech and sense of loyalty, Octavian allowed him to maintain his position in Judea, further isolating Antony and Cleopatra.[260]

Cleopatra perhaps started to view Antony as a liability by the late summer of 31 BC, when she prepared to leave Egypt to her son Caesarion.[261] As an object of Roman hostility, Cleopatra would relinquish her throne and remove herself from the equation by taking her fleet from the Mediterranean into the Red Sea and then setting sail to a foreign port, perhaps in India where she could spend time recuperating.[261][259] However, these plans were ultimately abandoned when Malichus I of Nabataea, as advised by Octavian's governor of Syria Quintus Didius, managed to burn Cleopatra's fleet, in revenge for his losses in a war with Herod largely initiated by Cleopatra.[261][259] Cleopatra had no option but to stay in Egypt and negotiate with Octavian.[261] Although most likely pro-Octavian propaganda, it was reported at this time that Cleopatra had begun testing the strengths of various poisons on prisoners and even her own servants.[262]

Cleopatra had Caesarion enter into the ranks of the ephebi. This, along with reliefs on a stele from Koptos dated 21 September 31 BC, demonstrate that she was now grooming her son to become the partial ruler of Egypt.[263] In a show of solidarity Antony also had Marcus Antonius Antyllus, his son with Fulvia, enter the ephebi at the same time.[261] Separate messages and envoys from Antony and Cleopatra were then sent to Octavia, still stationed at Rhodes, although Octavian seems to have replied only to Cleopatra.[262] Cleopatra requested that her children inherit Egypt and that Antony be allowed to live there in ecstasy. She offered Octavian money in the future and immediately sent him gifts of a golden scepter, crown, and throne.[262][259] Octavian sent his diplomat Thyrsos to Cleopatra after she had threatened to immolate herself and vast amounts of her treasure within a tomb already under construction.[264] Thyrsos advised her to kill Antony so that her life would be spared. When Antony suspected foul intent, however, he had this diplomat flogged and sent back to Octavian without a deal.[265] From Octavian's point of view, Lepidus could be trusted under house arrest. Antony, however, had to be eliminated, and Caesarion, the rival heir to Julius Caesar, could not be trusted either.[265]

After lengthy negotiations that ultimately produced no results, Octavian set out to invade Egypt in the spring of 30 BC.[266] He stopped at Ptolemais in Phoenicia where his new ally Herod entertained him and provided his army with fresh supplies.[267] Octavian moved south and swiftly took Pelousion, while Cornelius Gallus, marching eastward from Cyrene, defeated Antony's forces near Paraitonion.[268][269] Octavian advanced quickly to Alexandria. Antony returned and won a small victory over Octavian's tired troops outside the city's hippodrome.[268][269] However, on 1 August 30 BC Antony's naval fleet surrendered to Octavian, followed by his cavalry.[268][251][270] Cleopatra hid herself in her tomb with her close attendants, sending a message to Antony that she had committed suicide.[268][271][272] In despair, Antony responded by stabbing himself in the stomach, taking his own life at age 53.[268][251][259] According to Plutarch, however, Antony was allegedly still dying when he was brought to Cleopatra at her tomb. Plutarch told her Antony had died honorably in a contest against a fellow Roman, and that she could trust Octavian's companion Gaius Proculeius over anyone else in his entourage.[268][273][274] It was Proculeius, however, who infiltrated her tomb using a ladder and detained the queen, denying her the ability to immolate herself with her treasures.[275][276] Cleopatra was then allowed to embalm and bury Antony within her tomb before she was escorted to the palace.[275][259]

Octavian entered Alexandria and gave a speech of reconciliation at the gymnasium before settling in the palace and seizing Cleopatra's three youngest children.[275] When she met with Octavian she looked disheveled but still retained her poise and classic charm. She told him bluntly, "I will not be led in a triumph" (Ancient Greek: οὑ θριαμβεύσομαι, romanized: ou thriambéusomai) according to Livy, a rare recording of her exact words.[277][278] Octavian promised that he would keep her alive but offered no explanation about his plans for her kingdom.[279] When a spy informed her that Octavian planned to move her and her children to Rome in three days she prepared for suicide. She had no intention of being paraded in a Roman triumph like her sister Arsinoe IV.[279][251][259] It is unclear if Cleopatra's suicide, in August 30 BC at age 39, took place within the palace or her tomb.[280][281][note 1] It is said her servants Eiras and Charmion also took their own lives to accompany her.[279][282] Octavian was apparently angered by this outcome but had her buried in royal fashion next to Antony in her tomb.[279][283][284] Cleopatra's physician Olympos did not give an account of the cause of her death. The popular belief is that she allowed an asp, or Egyptian cobra, to bite and poison her.[285][286][259] Plutarch relates this tale, but then suggests an implement (knestis) was used to introduce the toxin by scratching. Cassius Dio says that she injected the poison with a needle (belone), and Strabo argued for an ointment of some kind.[287][286][288][note 32] No venomous snake was found with her body, but she did have tiny puncture wounds on her arm that could have been caused by a needle.[285][288][284]

Cleopatra, though long desiring to preserve her kingdom, decided in her last moments to send Caesarion away to Upper Egypt perhaps with plans to flee to Nubia, Ethiopia or India.[289][290][269] Caesarion, now Ptolemy XV, reigned for a mere eighteen days until he was executed on the orders of Octavian on 29 August 30 BC. He had been returning to Alexandria under the false pretense that Octavian would allow him to be king.[291][292][note 33] Octavian hesitated to have him killed at first, but the advice of philosopher and friend Arius Didymus convinced him there was room for only one Caesar in the world.[293] With the fall of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, Egypt was made into a Roman province.[294][251][295] This marked the end of Hellenistic Egypt and the entire Hellenistic age that had begun with the reign of Alexander the Great (336–323 BC) of Macedon.[296][297][note 2] In January 27 BC Octavian was renamed Augustus ('the revered') and amassed constitutional powers that established him as the first Roman emperor, inaugurating the Principate era of the Roman Empire.[298] Roman emperors were thereafter considered pharaohs of Egypt, but unlike the Ptolemaic rulers they did not reside in Egypt. Octavian, now Augustus, distanced himself from Egyptian royal rituals, such as coronation in the Egyptian style or worshiping the Apis bull.[222] He was, however, depicted in Egyptian temples as a typical pharaoh making sacrifices to the gods.[299] Unlike regular Roman provinces, Octavian established Egypt as territory under his personal control. He barred the Roman Senate from intervening in any of its affairs and appointed his own equestrian governors of Egypt, the first of whom was Cornelius Gallus.[300][301]

Egypt under the monarchy of Cleopatra

Right: a limestone stela of the High Priest of Ptah bearing the cartouches of Cleopatra and Caesarion, Egypt, Ptolemaic Period, the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Cleopatra's personal rule of Egypt followed the model of virtual absolute monarchy that had existed in the Kingdom of Macedon in northern Greece, the homeland of Alexander the Great, before he and his successors, the Diadochi, spread this style of monarchy throughout the conquered Achaemenid Persian Empire.[302] Classical Greece (480–336 BC) had contained a variety of city-states (i.e. poleis) possessing various forms of government, including democracy and oligarchy.[302] These city-states continued to have these forms of government in Hellenistic Greece (336–146 BC) and even later Roman Greece. They were heavily influenced and in many cases dominated by the Hellenistic monarchies of the Antigonid, Seleucid, and Ptolemaic realms.[302] Beginning with the reign of Ptolemy I Soter, founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty, the Ptolemaic Kingdom had fought a series of conflicts—the Syrian Wars—against the Seleucid Empire over control of Syria.[303] Cleopatra's kingdom was based in Egypt but she desired to expand it and incorporate territories of North Africa, West Asia, and the eastern Mediterranean Basin that had belonged to her illustrious ancestor Ptolemy I Soter.[304]

Cleopatra was nominally the sole lawgiver in her kingdom.[305] As proven by the discovery of a papyrus signed by Cleopatra granting tax exemptions to Antony's Roman colleague Quintus Cascellius, she was directly involved in the administrative affairs of her kingdom.[306] The Musaeum and adjacent Library of Alexandria attracted scholars from all over the Hellenistic world, who were also allowed to live in Egypt with total tax exemptions.[303] Cleopatra was also the chief religious authority in the kingdom, carrying out rituals and rites in the ancient Egyptian religion that her native Egyptian subjects viewed as preventing the destruction of the world.[307] Given the largely-Greek presence and multicultural nature of Ptolemaic cities like Alexandria,[308] Cleopatra was also obligated to oversee religious ceremonies honoring the various Greek deities.[307] Ethnic Greeks staffed the upper levels of government administrations, albeit within the framework of the scribal bureaucracy that had existed in Egypt since the Old Kingdom.[309] Many administrators of Cleopatra's royal court had served during her father's reign, although some of them were killed in the civil war between her and Ptolemy XIII.[310] The names of more than twenty regional governors serving under Cleopatra are known from inscriptions and papyri records, indicating some were ethnic Greeks and others were native Egyptians.[311]

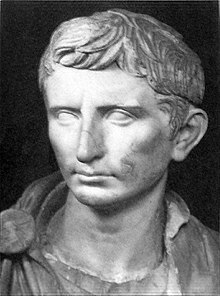

Right: the Vatican Cleopatra, a marble Roman bust of Cleopatra VII in the Vatican Museums, 40–30 BC

Two legally-defined classes divided Ptolemaic Egyptian society: Greeks and Egyptians. Macedonians and Greeks inhabited the city-states of Alexandria, Naukratis, and Ptolemais Hermiou. Considered full citizens of those poleis, they were forbidden to marry native Egyptians (although Greeks living outside of these municipalities could).[312] Native Egyptians and even Jews could be classified as Greeks if they abandoned their original cultures, received a Greek education, labeled their gods and goddesses with Greek names, and embraced the Greek lifestyle.[313] Native Egyptians had been largely excluded from serving in the military by the reign of Ptolemy II, replaced by Greek and Jewish landholders called cleruchs. By the reign of Ptolemy IV in the late 3rd century BC they were reintroduced as phalangite soldiers.[314] Large migrations of Greeks to Egypt ceased by the 2nd century BC, so that the Greek minority in Ptolemaic Egypt remained demographically small.[315]

Although Egyptian priests were often wealthy landowners who rivaled the wealth of the Ptolemaic pharaohs, the Ptolemaic monarchs technically owned all Egyptian lands as part of their estate.[316] Virtually all aspects of the Egyptian economy were nominally tightly controlled or supervised by the central government headquartered in Alexandria.[317][318] The Ptolemaic rulers exacted high tariffs on imported and exported goods, established price controls for various goods, imposed high exchange rates for foreign currencies, established state monopolies over certain industries such as vegetable oil and textile production, and forced farming peasants to stay in their villages during planting and harvesting periods.[317][318][319] However, the effectiveness of these policies and the authority of Ptolemaic rulers, including Cleopatra, to execute them fully were more of an ideal than a reality.[320] Cleopatra and many of her royal predecessors found it necessary to clear all the private debts of their subjects to the government at the start of their reigns, due to widespread financial corruption by local officials abusing the general populace.[321] Abuses often led workers to partake in general strikes until the government agreed to meet their demands.[321][322] At the beginning of her reign, local officials harassed destitute farmers by collecting taxes during a famine and drought. Cleopatra curtailed these predatory measures and introduced relief efforts such as releasing grain from the royal granary.[323]

Both Ptolemy XII and Cleopatra VII found it necessary to debase Ptolemaic coinage due to financial troubles.[324] No gold coins are known from Cleopatra's reign, while use of bronze coins was revived (absent since the reign of Ptolemy IX) and silver currency was debased roughly 40% by the end of her reign.[325] Coins struck under Cleopatra's reign came from a wide geographical expanse, including sites in Egypt like Alexandria, but also the island of Cyprus, Antioch, Damascus and Chalcis ad Belum in Syria, Tripolis in Phoenicia, Askalon in Judea, and Cyrenaica in Libya.[325] Surviving coins minted under Cleopatra include those from virtually every year of her reign.[326] They commonly bore an image of Cleopatra, along with that of the goddess Isis.[326] Some imitate the coinage of her Ptolemaic ancestor Arsinoe II. Coins struck with Mark Antony include Roman denarii with dual images of Cleopatra and Antony, the first time that a foreign queen appeared on Roman coins with Latin inscriptions.[327]

Right: ruins of the Temple of Montu at Hermonthis

In addition to various ancient Greco-Roman works of art and literature depicting the queen,[note 34] Cleopatra's legacy has partially survived in some of her ambitious building programs in Egypt utilizing Greek, Roman, and Egyptian styles of architecture.[329][330] She established a Caesareum temple dedicated to the worship of her partner Julius Caesar near the palatial seafront of Alexandria. Its entrance was flanked by 200-ton rose granite obelisks,[331] monuments placed there by Augustus in 13/12 BC. These were later known as Cleopatra's Needles and were relocated to New York and London in the 19th century.[332] In conjunction with renewing a grant of asylum to Jews in Egypt and the pro-Jewish policies of Julius Caesar, Cleopatra also erected a synagogue in Alexandria.[333][note 35] The city required extensive rebuilding following the civil war with her brother Ptolemy XIII, including necessary repairs to the Gymnasium and the Lighthouse of Alexandria on the island of Pharos.[334] It is not known if Cleopatra made significant repairs or alterations to the Library of Alexandria or the royal palace, although Lucan hints at the latter.[335] Cleopatra also began construction of her tomb (finished by Augustus) in the same palace precinct as the Tomb of Alexander the Great. Although the exact location of both of these is still unknown, Cleopatra's tomb may have served as the model for the Mausoleum of Augustus and that of later Roman emperors.[336]

Although established earlier, Cleopatra resumed construction of the Dendera Temple complex (near modern Qena, Egypt). Reliefs were made depicting Cleopatra and her son Caesarion presenting offerings to the deities Hathor and Ihy, mirroring images of offerings to Isis and Horus.[337][338] At the Hathor-Isis temple of Deir el-Medina, Cleopatra erected a large granite stela with dual inscriptions in Ancient Greek and Demotic Egyptian and images depicting her worshiping Montu and her son Caesarion worshiping Amun-Ra.[339] The cult center of Montu at Hermonthis was refashioned with images of Caesarion's divine birth by Julius Caesar, depicted as Amun-Ra. It included an elaborate facade and entrance kiosk with large columns bearing the cartouches of Cleopatra and Caesarion.[340][341] In the front entrance pylon of the Temple of Edfu, built by her father Ptolemy XII, Cleopatra erected two granite statues of Horus guarding the miniature figure of Caesarion.[342] Construction of a temple dedicated to the goddess Isis at Ptolemais Hermiou was overseen by Cleopatra's regional governor Kallimachos.[341]

See also

- Amanirenas (contemporary queen of Kush who fought a war against the Romans in Egypt and Nubia)

- Death of Cleopatra

- Early life of Cleopatra VII

- List of cultural depictions of Cleopatra

References

Notes

- ^ a b Theodore Cressy Skeat, in Skeat 1953, pp. 98–100, uses historical data to calculate the death of Cleopatra as having occurred on 12 August 30 BC. Burstein 2004, p. 31 provides the same date as Skeat, while Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 277 tepidly support this, saying it occurred circa that date. Those in favor of claiming her death occurred on 10 August 30 BC include Roller 2010, pp. 147–148, Fletcher 2008, p. 3, and Anderson 2003, p. 56.

- ^ a b Grant 1972, pp. 5–6 notes that the Hellenistic period, beginning with the reign of Alexander the Great (336–323 BC), came to an end with the death of Cleopatra in 30 BC. Michael Grant stresses that the Hellenistic Greeks were viewed by contemporary Romans as having declined and diminished in greatness since the age of Classical Greece, an attitude that has continued even into the works of modern historiography. In regards to Hellenistic Egypt, Grant argues that "Cleopatra VII, looking back upon all that her ancestors had done during that time, was not likely to make the same mistake. But she and her contemporaries of the first century BC had another, peculiar, problem of their own. Could the 'Hellenistic Age' (which we ourselves often regard as coming to an end in about her time) still be said to exist at all, could any Greek age, now that the Romans were the dominant power? This was a question never far from Cleopatra's mind. But it is quite certain that she considered the Greek epoch to be by no means finished, and intended to do everything in her power to ensure its perpetuation."

- ^ For further information, see Grant 1972, pp. 27–29

- ^ For further information, see Grant 1972, pp. 28–30

- ^ a b For further information, see Jones 2006, pp. 31, 34–35.

Fletcher 2008, pp. 85–86 states that the partial solar eclipse of 7 March 51 BC marked the death of Ptolemy XII Auletes and accession of Cleopatra to the throne, although she apparently suppressed the news of his death, alerting the Roman Senate to this fact months later in a message they received on 30 June 51 BC.

However, Grant 1972, p. 30 claims that the Senate was informed of his death on 1 August 51 BC. Michael Grant indicates that Ptolemy XII could have been alive as late as May, while an ancient Egyptian source affirms he was still ruling with Cleopatra by 15 July 51 BC, although by this point Cleopatra most likely "hushed up her father's death" so that she could consolidate her control of Egypt. - ^ For further information see Fletcher 2008, pp. 88–92 and Jones 2006, pp. 31, 34–35.

- ^ Pfrommer & Towne-Markus 2001, p. 34 write the following about the incestuous marriage of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II, who introduced the practice of sibling marriage into the Ptolemaic dynasty: "Ptolemy Keraunos, who wanted to become king of Macedon...killed Arsinoë's small children in front of her. Now queen without a kingdom, Arsinoë fled to Egypt, where she was welcomed by her full brother Ptolemy II. Not content, however, to spend the rest of her life as a guest at the Ptolemaic court, she had Ptolemy II's wife exiled to Upper Egypt and married him herself around 275 B.C. Though such an incestuous marriage was considered scandalous by the Greeks, it was allowed by Egyptian custom. For that reason the marriage split public opinion into two factions. The loyal side celebrated the couple as a return of the divine marriage of Zeus and Hera, whereas the other side did not refrain from profuse and obscene criticism. One of the most sarcastic commentators, a poet with a very sharp pen, had to flee Alexandria. The unfortunate poet was caught off the shore of Crete by the Ptolemaic navy, put in an iron basket, and drowned. This and similar actions seemingly slowed down vicious criticism."

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher 2008, pp. 92–93

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher 2008, p. 96 and Jones 2006, p. 39.

- ^ a b For further information, see Fletcher 2008, p. 98 and Jones 2006, pp. 39–43, 53–55.

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher 2008, pp. 98–100 and Jones 2006, pp. 53–55

- ^ For further information, see Burstein 2004, p. 18 and Fletcher 2008, pp. 101–103.

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher 2008, p. 113.

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher 2008, p. 118.

- ^ For further information, see Burstein 2004, pp. xxi, 19 and Fletcher 2008, pp. 118–119.

- ^ For further information, see Burstein 2004, p. 76.

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher 2008, pp. 119–120.

For the Siege of Alexandria (47 BC), Burstein 2004, p. 19 states that Julius Caesar's reinforcements came in January, but Roller 2010, p. 63 says that his reinforcements came in March. - ^ For further information, see Fletcher 2008, p. 120.

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher 2008, p. 121.

Roller 2010, pp. 64–65 states that at this point (47 BC) Ptolemy XIV was 12 years old, while Burstein 2004, p. 19 claims that he was still only 10 years of age. - ^ For further information, see Fletcher 2008, p. 125.

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher 2008, p. 154 and Burstein 2004, pp. xxi, 20, 64.

- ^ Roller 2010, p. 70 writes the following about Julius Caesar and his parentage of Caesarion: "The matter of parentage became so tangled in the propaganda war between Antonius and Octavian in the late 30s B.C.–it was essential for one side to prove and the other to reject Caesar's role–that it is impossible today to determine Caesar's actual response. The extant information is almost contradictory: it was said that Caesar denied parentage in his will but acknowledged it privately and allowed use of the name Caesarion. Caesar's associate C. Oppius even wrote a pamphlet proving that Caesarion was not Caesar's child, and C. Helvius Cinna–the poet who was killed by rioters after Antonius's funeral oration–was prepared in 44 B.C. to introduce legislation to allow Caesar to marry as many wives as he wished for the purpose of having children. Although much of this talk was generated after Caesar's death, it seems that he himself wished to be as quiet as possible about the child but had to contend with Cleopatra's repeated assertions."

- ^ For further information and validation, see Jones 2006, pp. xiv, 78.

- ^ For further information, see Burstein 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Fletcher 2008, p. 87 describes the painting from Herculaneum further: "Cleopatra's hair was maintained by her highly skilled hairdresser Eiras. Although rather artificial looking wigs set in the traditional tripartite style of long straight hair would have been required for her appearances before her Egyptian subjects, a more practical option for general day-to-day wear was the no-nonsense 'melon hairdo' in which her natural hair was drawn back in sections resembling the lines on a melon and then pinned up in a bun at the back of the head. A trademark style of Arsinoe II and Berenike II, the style had fallen from fashion for almost two centuries until revived by Cleopatra; yet as both traditionalist and innovator, she wore her version without her predecessor's fine head veil. And whereas they had both been blonde like Alexander, Cleopatra may well have been a redhead, judging from the portrait of a flame-haired woman wearing the royal diadem surrounded by Egyptian motifs which has been identified as Cleopatra."

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 301 claims that Octavia Minor provided Mark Antony with 1,200 troops, not 2,000 as stated in Roller 2010, pp. 97–98 and Burstein 2004, pp. 27–28

- ^ Ferroukhi (2001a, p. 219) provide a detailed discussion about this bust and its ambiguities, noting that it could represent Cleopatra, but that it is more likely her daughter Cleopatra Selene II. Kleiner (2005, pp. 155–156) harvtxt error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKleiner2005 (help) argues in favor of it depicting Cleopatra rather than her daughter, while Varner (2004, p. 20) only mentions Cleopatra as a possible likeness. Roller (2003, p. 139) observes that it could be either Cleopatra or Cleopatra Selene II, while arguing the same ambiguity applies to the other sculpted head from Cherchel featuring a veil. In regards to the latter head, Ferroukhi (2001b, p. 242) indicates it as a possible portrait of Cleopatra, not Cleoptra Selene II, from the early 1st century AD while also arguing that its masculine features, earrings, and apparent toga (the veil being a component of it) could likely mean it was intended to depict a Numidian nobleman. Fletcher (2008, image plates between pp. 246–247) disagrees about the veiled head, arguing that it was commissioned by Cleopatra Selene II at Iol (Caesarea Mauretaniae) and was meant to depict her mother, Cleopatra.

- ^ Walker (2001, p. 312) writes the following about the raised relief on the gilded silver dish: "Conspicuously mounted on the cornucopia is a gilded crescent moon set on a pine cone. Around it are piled pomegranates and bunches of grapes. Engraved on the horn are images of Helios (the sun), in the form of a youth dressed in a short cloak, with the hairstyle of Alexander the Great, the head surrounded by rays... The symbols on the cornucopia can indeed be read as references to the Ptolemaic royal house and specifically to Cleopatra Selene, represented in the crescent moon, and to her twin brother, Alexander Helios, whose eventual fate after the conquest of Egypt is unknown. The viper seems to be linked with the pantheress and the intervening symbols of fecunditity rather than the suicide of Cleopatra VII. The elephant scalp could refer to Cleopatra Selene's status as ruler, with Juba II, of Mauretania. The visual correspondence with the veiled head from Cherchel encourages this identification, and many of the symbols used on the dish also appear on the coinage of Juba II."

- ^ Roller 2010, p. 100 says that it is unclear if they were ever truly married, while Burstein 2004, p. 29 says that the marriage publicly sealed Antony's alliance with Cleopatra, in defiance of Octavian now that he was divorced from Octavia.

- ^ Stanley M. Burstein, in Burstein 2004, p. 33 provides the name Quintus Cascellius as the recipient of the tax exemption, not the Publius Canidius Crassus provided by Duane W. Roller in Roller 2010, p. 134.

- ^ As explained by Jones 2006, p. 147: "politically, Octavian had to walk a fine line as he prepared to engage in open hostilities with Antony. He was careful to minimize associations with civil war, as the Roman people had already suffered through many years of civil conflict and Octavian could risk losing support if he declared war on a fellow citizen."

- ^ For the translated accounts of both Plutarch and Cassius Dio, Jones 2006, pp. 194–195 writes that the implement used to puncture Cleopatra's skin was a hairpin.

- ^ Roller 2010, p. 149 and Skeat 1953, pp. 99–100 explain the nominal short-lived reign of Caesarion, or Ptolemy XV, as lasting eighteen days in August 30 BC. However, Duane W. Roller, relaying Theodore Cressy Skeat, affirms that Caesarion's reign "was essentially a fiction created by Egyptian chronographers to close the gap between [Cleopatra's] death and official Roman control of Egypt (under the new pharaoh, Octavian)," citing, for instance, the Stromata by Clement of Alexandria (Roller 2010, pp. 149, 214, footnote 103).

Plutarch, translated by Jones 2006, p. 187, wrote in vague terms that "Octavian had Caesarion killed later, after Cleopatra's death." - ^ For a survey of ancient visual arts and works of literature depicting Cleopatra, see Roller 2010, pp. 7–9, 173–184.

- ^ Roller 2010, p. 104 mentions that Cleopatra also renewed the license of another synagogue, perhaps at Leontopolis.

Citations

- ^ a b Raia & Sebesta (2017).

- ^ Lippold (1936), pp. 169–171.

- ^ Curtius (1933), pp. 184 ff. Abb. 3 Taf. 25—27..

- ^ Ashton (2001b), p. 165.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Burstein (2004), p. 14.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 80, 85.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 27.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xx, 14.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 53, 56.

- ^ a b Fletcher (2008), pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Grant (1972), p. 30.

- ^ a b c Hölbl (2001), p. 231.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xx, 15–16.

- ^ Burstein (2004), p. xx.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 114.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 53.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. 16.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 91–92.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 24–26, 53–54.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. 13–14, 16–17.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 92.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 199–200.

- ^ Ashton (2001a), p. 217.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 54–56.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 56.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 56–57.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 73, 92–93.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 57.

- ^ a b c Burstein (2004), pp. xx, 17.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 58.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 95.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 58–59.

- ^ Burstein (2004), p. 17.