Khusrau Mirza

| Khusrau Mirza | |

|---|---|

| Mirza[1] Shahzada of the Mughal Empire | |

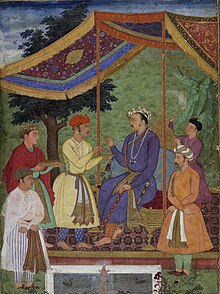

Emperor Jahangir receiving his two sons, Khusrau and Parviz, an album-painting in gouache on paper, c. 1605-06 | |

| Born | 16 August 1587 Lahore, Mughal Empire |

| Died | 26 January 1622 (aged 34) Deccan |

| Burial | |

| Wives | Daughter of Mirza Aziz Koka Daughter of Jani Beg Tarkhan of Thatta Daughter of Muqim, son of Mihtar Fazil Rikabdar |

| Issue | Dawar Bakhsh Buland Akhtar Mirza Gurshasp Mirza Hoshmand Banu Begum |

| House | Timurid |

| Father | Jahangir |

| Mother | Shah Begum |

| Religion | Islam |

Khusrau Mirza (Urdu:خسرو مِرزا) (16 August 1587 – 26 January 1622) was the eldest son of the Mughal emperor Jahangir.[2]

Early life

Khusrau was born in Lahore on August 16, 1587.[3] His mother, Manbhawati Bai (who was given the title Shah Begam after his birth), was the daughter of Raja Bhagwant Das of Amber (Jaipur), head of the Kachhwaha clan of Rajputs. She committed suicide on May 16, 1605, by consuming opium.[4]

Family

Khusrau's first wife and chief consort was the daughter of extremely powerful Mirza Aziz Koka, known as Khan Azam, son of Jiji Anga, Emperor Akbar's foster mother. When Khusrau's marriage was arranged with her, an order was given that S'aid Khan Abdullah Khan and Mir Sadr Jahan should convey 100,000 rupees[5] as sachaq to the Mirza's house by the way of Sihr baha.[6] She was his favourite wife, and was the mother of his eldest son, Dawar Bakhsh,[7] and his second son, Prince Buland Akhtar Mirza, born on 11 March 1609, who died in infancy.[8]

Another of Khusrau's wives was the daughter of Jani Beg Tarkhan of Thatta.[9] She was the sister of Mirza Ghazi Beg. The marriage was arranged by Khusrau's grandfather, Emperor Akbar.[10][11] Another of his wives was the daughter of Muqim, son of Mihtar Fazil Rikabdar (stirrup holder). She was the mother of Prince Gurshasp Mirza, born on 8 April 1616.[12][13] Khusrau had a daughter, Hoshmand Banu Begum, born in about 1605, and married to Prince Hoshang Mirza, son of Prince Daniyal Mirza.[14]

Rebellion and aftermath

In 1605, Emperor Akbar died. Akbar had been deeply disappointed with Khusrau's father, Jahangir. Perhaps due to this background, Khusrau rebelled against his father in 1606 to secure the throne for himself.

Khusrau left Agra on April 6, 1606[15] with 350 horsemen on the pretext of visiting the tomb of Akbar at nearby Sikandra. In Mathura, he was joined by Hussain Beg, with about 3000 horsemen. In Panipat, he was joined by Abdur Rahim, the provincial dewan (administrator) of Lahore. When Khusrau reached Taran Taran near Amritsar, he received the blessings of Guru Arjan Dev.[16]

Khusrau laid siege on Lahore, defended by Dilawar Khan. Jahangir soon reached Lahore with a large army and Khusrau was defeated in the battle of Bhairowal. He and his followers tried to flee towards Kabul, but they were captured by Jahangir's army while crossing the Chenab.[17]

Khusrau was first brought to Delhi, where a novel punishment was meted out to him. He was seated in grand style on an elephant and paraded down Chandni Chowk, while on both sides of the narrow street, the noblemen and barons who had supported him were held at knife-point on raised platforms. As the elephant approached each such platform, the luckless supporter was impaled on a stake (through his bowels), while Khusrau was compelled to watch the grisly sight and listen to the screams and pleas of those who had supported him. This was repeated numerous times through the entire length of Chandni Chowk.

Khusrau was then blinded (in 1607) and imprisoned in Agra. However, his eyesight was never completely lost. In 1616, he was handed over to Asaf Khan, the brother of his step-mother Nur Jehan. In 1620, he was handed over to his younger brother, Prince Khurram (later known as emperor Shah Jahan), who incidentally was Asaf Khan's son-in-law. In 1622, Khusrau was killed on the orders of Prince Khurram.[18][19]

Posterity

After the death of Jahangir in 1627, Khusrau's son, Prince Dawar was briefly made ruler of the Mughal Empire by Asaf Khan to secure the Mughal throne for Shah Jahan.

On Jumada-l awwal 2, 1037 AH (December 30, 1627[20]), Shah Jahan was proclaimed as the emperor at Lahore. On Jumada-l awwal 26, 1037 AH (January 23, 1628[20]), Dawar, his brother Garshasp, uncle Shahryar, as well as Tahmuras and Hoshang, sons of the deceased Prince Daniyal, were all put to death by Asaf Khan,[21] who was ordered by Shah Jahan to send them "out of the world", which he faithfully carried out.[22]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Khusrau Mirza | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ^ Mughla title Mirza, the title of Mirza and not Khan or Padshah, which were the titles of the Mongol rulers.

- ^ The Grandees of the Empire Ain-i-Akbari, by Abul Fazl, Volume I, Chpt. 30.

- ^ Beveridge, H. (tr.) (1939, reprint 2000) The Akbar Nama of Abu'l-Fazl, Vol.III, Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, ISBN 81-7236-094-0, p.799

- ^ Beveridge, H. (tr.) (1939, reprint 2000) The Akbar Nama of Abu'l-Fazl, Vol.III, Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, ISBN 81-7236-094-0, p.1239

- ^ Smart, Ellen S.; Walker, Daniel S. (1985). Pride of the princes: Indian art of the Mughal era in the Cincinnati Art Museum. Cincinnati Art Museum. p. 27.

- ^ Mukhia, Harbans (April 15, 2008). The Mughals of India. John Wiley & Sons. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-470-75815-1.

- ^ Shujauddin, Mohammad; Shujauddin, Razia (1967). The Life and Times of Noor Jahan. Caravan Book House. p. 70.

- ^ Jahangir, Rogers & Beveridge 1909, p. 153.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (1997). Akbar and His India. Oxford University Press. p. 50.

- ^ Jahangir, Emperor; Thackston, Wheeler McIntosh (1999). The Jahangirnama : memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Washington, D. C.: Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 30, 136.

- ^ Hasan Siddiqi, Mahmudul (1972). History of the Arghuns and Tarkhans of Sindh, 1507–1593: An Annotated Translation of the Relevant Parts of Mir Ma'sums Ta'rikh-i-Sindh, with an Introduction & Appendices. Institute of Sindhology, University of Sind. p. 205.

- ^ Jahangir, Rogers & Beveridge 1909, p. 321.

- ^ Jahangir, Emperor; Thackston, Wheeler McIntosh (1999). The Jahangirnama : memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Washington, D. C.: Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 192.

- ^ Jahangir, Emperor; Thackston, Wheeler McIntosh (1999). The Jahangirnama : memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Washington, D. C.: Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 97, 436.

- ^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.)(2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, p.179

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (Jan 15, 2014). Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History. ABC-CLIO. p. 1163. ISBN 9781610690263. Retrieved Nov 3, 2014.

- ^ The Flight of Khusrau The Tuzk-e-Jahangiri Or Memoirs Of Jahangir, Alexander Rogers and Henry Beveridge. Royal Asiatic Society, 1909–1914. Vol. I, Chapter 3. p 51, 62-72., Volume 1, chpt. 20

- ^ Mahajan V.D. (1991, reprint 2007) History of Medieval India, Part II, New Delhi: S. Chand, ISBN 81-219-0364-5, pp.126-7

- ^ Ellison Banks Findly (25 March 1993). Nur Jahan: Empress of Mughal India. Oxford University Press. pp. 170–172. ISBN 978-0-19-536060-8.

- ^ a b Taylor, G.P. (1907). Some Dates Relating to the Mughal Emperors of India in Journal and Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, New Series, Vol.3, Calcutta: The Asiatic Society of Bengal, p.59

- ^ Death of the Emperor (Jahangir) The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period, Sir H. M. Elliot, London, 1867–1877, vol 6.

- ^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.)(2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp.197-8

- ^ a b Asher, Catherine Blanshard (1992). Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-521-26728-1.

- ^ a b Srivastava, M. P. (1975). Society and Culture in Medieval India, 1206-1707. Allahabad: Chugh Publications. p. 178.

- ^ Mohammada, Malika (2007). The Foundations of the Composite Culture in India. Delhi: Aakar Books. p. 300. ISBN 978-81-89833-18-3.

- ^ a b Gulbadan Begum (1902). The History of Humayun (Humayun-nama). Translated by Annette Beveridge. London: Royal Asiatic Society. pp. 157–58.

- ^ Latif, Syad Muhammad (2003). Agra Historical and Descriptive with an Account of Akbar and His Court and of the Modern City of Agra. Asian Educational Services. p. 156. ISBN 978-81-206-1709-4.

- ^ Agrawal, C. M. (1986). Akbar and his Hindu officers: a critical study. ABS Publications. p. 27.

- ^ Sarkar, Jadunath (1984). A History of Jaipur: C. 1503-1938. Orient Longman Limited. p. 43. ISBN 81-250-0333-9.

- ^ Prasad, Rajiva Nain (1966). Raja Man Singh of Amber. Calcutta: World Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8426-1473-3.

- ^ Bhatnagar, V. S. (1974). Life and Times of Sawai Jai Singh, 1688-1743. Delhi: Impex India. p. 10.

Bibliography

- Jahangir, Emperor; Rogers, Alexander; Beveridge, Henry (1909). The Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri; or, Memoirs of Jahangir. Translated by Alexander Rogers. Edited by Henry Beveridge. London Royal Asiatic Society. pp. 78, 81, 279.