Alexander Jannaeus

- For other rulers related or affiliated with Alexander Jannaeus, see List of Hasmonean and Herodian rulers

| Alexander Jannaeus | |

|---|---|

| King and High Priest of Judaea | |

Alexander Jannaeus, woodcut designed by Guillaume Rouillé. From Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum. | |

| Reign | c. 103 – 76 BC (27 years)[1] |

| Predecessor | Aristobulus I |

| Successor | Salome Alexandra |

| Born | C. 127 BC |

| Died | C. 76 BC |

| Dynasty | Hasmonean |

| Father | John Hyrcanus I |

| Religion | Hellenistic Judaism |

Alexander Jannaeus (also known as Alexander Jannai/Yannai; Template:Lang-he-n, born Jonathan Alexander) was the second Hasmonean king of Judaea from 103 to 76 BC. A son of John Hyrcanus, he inherited the throne from his brother Aristobulus I, and married his brother's widow, Queen Salome Alexandra. From his conquests to expand the kingdom to a bloody civil war, Alexander's reign has been generalized as cruel and oppressive with never ending conflict.[2] Although Josephus and other historians refer to him by the name of "Alexander Yannai", his full name was "Alexander Jonathan" as attested to by his coins wherein he calls himself "Yehonathan the king".[3]

Family

Alexander Jannaeus was the third son of John Hyrcanus, by his second wife. When Aristobulus I, Hyrcanus' son by his first wife, became king, he deemed it necessary for his own security to imprison his half-brother. Aristobulus died after a reign of one year. Upon his death, his widow, Salome Alexandra had Alexander and his brothers released from prison.

Alexander, as the oldest living brother, had the right not only to the throne but also to Salome, the widow of his deceased brother, who had died childless; and, although she was thirteen years older than him, he married her in accordance with Jewish law. By her, he had two sons, the eldest, Hyrcanus II became high-priest in 62 BC and Aristobulus II who was high-priest from 66 - 62 BC and started a bloody civil war with his brother, ending in his capture by Pompey the Great. Like his brother he was an avid supporter of the aristocratic priestly faction known as the Sadducees, his wife Salome on the other hand came from a pharisaic family (her brother was Simeon ben Shetach a famous pharisee leader), and was more sympathetic to their cause and protected them throughout his turbulent reign.[4] Like his father Alexander also served as the high priest. This raised the ire of the Rabbis who insisted that these two offices should not be combined. According to the Talmud, Yannai was a questionable desecrated priest (rumour had it that his mother was captured in Modiin and violated) and was not allowed to serve in the temple according to the rabbis, this infuriated the king and sided with the Sadducees who defended him. This incident led the king to turn against the pharisees and persecute them until his death.

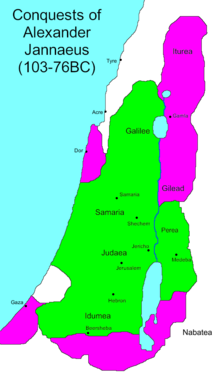

Conquests

War with Ptolemy Lathyrus

Alexander's first expedition was against the city of Ptolemais (Acre). While Alexander went forward to siege the city, Zoilus, ruler of the coastal city Dora and Straton's Tower took the opportunity to see if he could perhaps save Ptolemais in hopes of gaining territory. Alexander's Hasmonean army quickly defeated Zoilus's forces with little trouble. Ptolemais and Zoilus then requested aid from Ptolemy IX Lathyros, who had been cast out by his mother Cleopatra III. Ptolemy founded a kingdom in Cyprus after being cast out by his mother. The situation at Ptolemais was seized as an opportunity by Ptolemy to possibly gain a stronghold and control the Judean coast in order to invade Egypt.[5]

Ptolemy landed a large army for the relief of the town; but Alexander met him with treachery, arranging an alliance with him openly while secretly he sought to obtain the help of his mother against him. When Alexander formed an alliance with Ptolemy, Ptolemy in good gesture, handed over Ptolemais, Zoilus, Dora, and Straton's Tower to Alexander.[6] As soon as Ptolemy learned of Alexander's scheme, he invaded the Galilee region capturing Asochis.[7][8] Ptolemy also initiated an attack upon Sepphoris but failed.[9]

Alexander might easily have lost his crown and Judea its independence as the result of this battle, had it not been for the assistance extended by Egypt. Cleopatra's two Jewish generals, Helkias and Ananias, persuaded the queen of the dangers of allowing her banished son Ptolemy to remain victorious and she entrusted them with an army against him. As a result, Ptolemy was forced to withdraw to Cyprus, and Alexander was saved. The Egyptians, as compensation for their aid, desired to annex Judea to their country, but considerations touching the resident Egyptian Jews, who were the main support of her throne, induced Cleopatra to modify her longings for conquest. The Egyptian army withdrawn, Alexander found his hands free; and forthwith he planned new campaigns.[10][11]

Transjordan and coastal conquest

Alexander captured Gadara and the strong fortress Amathus in the Transjordan region; but, in an ambush set for him by Theodorus, ruler of Amathus, he lost the battle. Alexander was more successful in his expedition against the Hellenized coastal cities (what had once been Philistia), capturing Raphia and Anthedon. Finally, in 96 BC[12] Jannaeus outlasted the inhabitants of Gaza in a year-long siege, which he occupied through treachery, and gave up to be pillaged and burned by his soldiery. This victory gained Judean control over the Mediterranean outlet of the Nabatean trade routes.[13]

Judean Civil War

The Judean Civil War initially began after the conquest of Gaza by Jannaeus around 96 BC. Due to Jannaeus's victory at Gaza, the Nabatean kingdom no longer controlled their main trade route to the Mediterranean Sea at Gaza and to the road leading to Damascus. Therefore, the Nabatean king Obodas I launched an ambush on Alexander in a steep valley in Gadara where Jannaeus "was lucky to escape alive".[14] After Jannaeus was defeated in the Battle of Gadara against the Nabataeans, he returned to fierce Jewish opposition in Jerusalem.[15] Alexander had to cede the acquired territories to the Nabataeans so that he could dissuade Obodas from supporting his opponents in Judea.[14]

During the Jewish holiday of Feast of Tabernacles, Alexander Jannaeus, while officiating as the High Priest at the Temple in Jerusalem, demonstrated his support of the Sadducees by refusing to perform the water libation ceremony properly: instead of pouring it on the altar, he poured it on his feet. The crowd responded with shock at his mockery and showed their displeasure by pelting Alexander with the etrogim (citrons) that they were holding in their hands. Outraged, he ordered soldiers to kill those who insulted him, more than 6,000 people in the Temple courtyard were massacred. With further frustration, Alexander had wooden barriers built around the altars preventing people from sacrificing and denied daily offerings except for the priests. He also allied himself with foreign troops such as the Pisidians and the Cilicians who would later help his regime during the civil war.[15] This incident during the Feast of Tabernacles was a major factor leading up to the Judean Civil War by igniting popular opposition to Jannaeus.[16][17]

Overall, the war lasted six years and left 50,000 Judeans dead. After Jannaeus succeeded early in the war, the rebels asked for Seleucid assistance. Judean insurgents joined forces with Demetrius III Eucaerus to fight against Jannaeus. The Seleucid forces defeated Jannaeus at Shechem and forced him to take refuge in the mountains. However, these Judean rebels ultimately decided that it was better to live under a terrible Jewish king than return to a Seleucid ruler. After 6,000 Jews returned to Jannaeus, Demetrius was defeated. The end of the Civil War brought a sense of national solidarity against Seleucid influence. Nevertheless, Jannaeus was uninterested in reconciliation within the Judean State.[15][17]

The aftermath of the Judean Civil War consisted of popular unrest, poverty and grief over the fallen soldiers on both sides. The greatest impact of the war was the victor's revenge. Josephus reports that Jannaeus brought 800 Pharisee rebels to Jerusalem and had them crucified, and had the throats of the rebel's wives and children cut before their eyes as Jannaeus ate with his concubines.[1][18][19]

Coinage

The coinage of Alexander Jannaeus is characteristic of the early Jewish coinage in that it avoided human or animal representations, in opposition to the surrounding Greek, and later Roman types of the period. Jewish coinage instead focused on symbols, either natural, such as the palm tree, the pomegranate or the star, or man-made, such as the Temple, the Menorah, trumpets or cornucopia.

Obv: Seleucid anchor and Greek Legend: BASILEOS ALEXANDROU "King Alexander".

Rev: Eight-spoke wheel or star within diadem. Hebrew legend inside the spokes: "Yehonatan the King".

Alexander Jannaeus was the first of the Jewish kings to introduce the "eight-ray star" or "eight-spoked wheel" symbol, in his bronze "Widow's mite" coins, in combination with the widespread Seleucid numismatic symbol of the anchor. Depending on the make, the star symbol can be shown with straight spokes connected to the outside circle, in a style rather indicative of a wheel. On others, the spokes can have a more "flame-like" shape, more indicative of the representation of a star within a diadem.

It is not clear what the wheel or star may exactly symbolize, and interpretations vary, from the morning star, to the sun or the heavens. The influence of some Persian symbols of a star within a diadem, or the eight-spoked Buddhist wheel (see the coins of the Indo-Greek king Menander I with this symbol) have also been suggested. The eight-spoked Macedonian star (a variation of which is the Vergina Sun), emblem of the royal Argead dynasty and the ancient kingdom of Macedonia, within a Hellenistic diadem symbolizing royalty (many of the coins depict a small knot with two ends on top of the diadem), seem to be the most probable source for this symbol.

The most likely explanation is that the symbol is a star encased in a diadem and it is a religious explanation. Biblical law forbids the making of graven images for worship, yet the image of a monarch is a staple of Hellenistic coins. In place of an image of himself, therefore, it is likely that Alexander Jannaeus chose a star, in keeping with Numbers 24:17, "A star rises from Jacob, a sceptre comes forth from Israel". This verse generally was seen as a biblical support for monarchy (and specifically as support for a Davidic monarchy). Jannaeus, however, could have seen it as an image of his achievements, if not his own rule. This is how the rest of Numbers 24:17 and verses 18 and 19 continue: The star, it says, "smashes the brow of Moab, the foundation of all children of Seth. Edom becomes a possession, yea, Seir a possession of its enemies; but Israel is triumphant. A victor issues from Jacob to wipe out what is left of Ir". Considering Jannaeus' conquests—creating a kingdom that rivalled those of David and Solomon and may have even exceeded those—the "star" envisioned in the prophecy of Balaam in Numbers was a perfect match for him.

Citations

- ^ a b Stegemann 1998, p. 130.

- ^ Saldarini 2001, p. 89.

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library, Yannai Alexander

- ^ New World Encyclopedia, Alexander Jannaeus

- ^ Atkinson 2012, p. 131.

- ^ Schürer, Vermes & Millar 2014, p. 116.

- ^ Davies & Finkelstein 1984, p. 600.

- ^ Kasher 1998, p. 80.

- ^ Finegan 2015, p. 223.

- ^ Borgen 1998, p. 84.

- ^ Bar-Kochva 2010, p. 93.

- ^ Negev & Gibson 2005.

- ^ Schäfer 2003, pp. 74 & 75.

- ^ a b Jane, Taylor (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. London, United Kingdom: I.B.Tauris. pp. 14, 17, 30, 31. ISBN 9781860645082. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Eshel 2008, pp. 117–123.

- ^ Kaiser 1998, p. 482.

- ^ a b Rasmussen 2014.

- ^ Crossan 1999, p. 462.

- ^ Hengel 1977, p. 84.

Bibliography

- Atkinson, Kenneth (2012). Queen Salome: Jerusalem's Warrior Monarch of the First Century B.C.E. McFarland. ISBN 9780786490738.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bar-Kochva, Bezalel (2010). The Image of the Jews in Greek Literature: The Hellenistic Period. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520943636.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Borgen, Peter (1998). Early Christianity and Hellenistic Judaism. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567086266.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crossan, John Dominic (1999). Birth of Christianity (Reprint ed.). A&C Black. ISBN 9780567086686.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, William David; Finkelstein, Louis (1984). The Cambridge History of Judaism: The early Roman period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243773.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eshel, Hanan (2008). The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonean State. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802862853.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Finegan, Jack (2015). Light from the Ancient Past. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400875153.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hengel, Martin (1977). Crucifixion: In the Ancient World and the Foll of the Message of the Cross. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451414196.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kaiser, Walter C. (1998). History of Israel. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 9780805431223.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kasher, Aryeh (1998). Jews, Idumaeans, and Ancient Arabs: Relations of the Jews in Eretz-Israel with the Nations of the Frontier and the Desert During the Hellenistic and Roman Era. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161452406.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Negev, Avraham; Gibson, Shimon (2005). Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land (Illustrated, Revised ed.). Continuum. ISBN 9780826485717.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rasmussen, Carl G. (2014). Zondervan Atlas of the Bible (Revised ed.). Harper Collins. ISBN 9780310521266.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Saldarini, Anthony J. (2001). Pharisees, Scribes and Sadducees in Palestinian Society: A Sociological Approach. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802843586.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schäfer, Peter (2003). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest (2nd Revised ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781134403165.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schürer, Emil; Vermes, Geza; Millar, Fergus (2014). The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ. A&C Black. ISBN 9781472558299.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stegemann, Hartmut (1998). The Library of Qumran: On the Essenes, Qumran, John the Baptist, and Jesus. BRILL. ISBN 9789004112100.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Leptons and Prutahs of Alexander Jannaeus

- Miniature 'shield' showing the 8-spoked star of the Argead

- Information on Salome Alexandra and Alexander Jannaeus by the author of Queen of the Jews

- "Jannaeus, His Brother Absalom,and Judah the Essene," By Stephen Goranson. Jannaeus as the Qumran text's "Wicked Priest."