Balkan Wars

| Balkan Wars | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prilep Battle 1912 Postcard | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

First Balkan War Support |

First Balkan War Support | |||||||

|

Second Balkan War |

Second Balkan War | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

| |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Events leading to World War I |

|---|

|

|

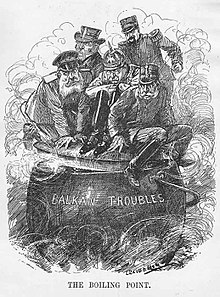

The Balkan Wars (Turkish: Balkan Savaşları, literally "the Balkan Wars" or Balkan Faciası, meaning "the Balkan Tragedy") consisted of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan Peninsula in south-eastern Europe in 1912 and 1913. Four Balkan states defeated the Ottoman Empire in the first war; one of the four, Bulgaria, suffered defeat in the second war. The Ottoman Empire lost the bulk of its territory in Europe. Austria-Hungary, although not a combatant, became relatively weaker as a much enlarged Serbia pushed for union of the South Slavic peoples.[2] The war set the stage for the Balkan crisis of 1914 and thus served as a "prelude to the First World War".[3]

By the early 20th century, Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia had achieved independence from the Ottoman Empire, but large elements of their ethnic populations remained under Ottoman rule. In 1912 these countries formed the Balkan League. The First Balkan War had three main causes:[4][5]

- The Ottoman Empire was unable to reform itself, govern satisfactorily, or deal with the rising ethnic nationalism of its diverse peoples.

- The Great Powers quarreled amongst themselves and failed to ensure that the Ottomans would carry out the needed reforms. This led the Balkan states to impose their own solution.

- Most importantly, the Balkan League had been formed, and its members were confident that it could defeat the Turks.

The Ottoman Empire lost all its European territories to the west of the River Maritsa as a result of the two Balkan Wars, which thus delineated present-day Turkey's western border. A large influx of Turks started to flee into the Ottoman heartland from the lost lands. By 1914, the remaining core region of the Ottoman Empire had experienced a population increase of around 2.5 million because of the flood of immigration from the Balkans.

Citizens of Turkey regard the Balkan Wars as a major disaster (Balkan harbi faciası) in the nation's history. The unexpected fall and sudden relinquishing of Turkish-dominated European territories created a psycho-traumatic event amongst many Turks that is said[by whom?] to have triggered the ultimate collapse of the empire itself within five years. Nazım Pasha, Chief of Staff of the Ottoman Army, was held responsible for the failure and was assassinated on 23 January 1913 during the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état carried out by the "Young Turks".

The First Balkan War began when the League member states attacked the Ottoman Empire on 8 October 1912 and ended eight months later with the signing of the Treaty of London on 30 May 1913. The Second Balkan War was begun on 16 June 1913. Both Serbia and Greece, utilizing the argument that the war had been prolonged, repudiated important particulars of the pre-war treaty and retained occupation of all the conquered districts in their possession which were to be divided according to specific predefined boundaries. Seeing the treaty as trampled, Bulgaria was dissatisfied over the division of the spoils in Macedonia (made in secret by its former allies, Serbia and Greece) and commenced military action against them. The more numerous combined Serbian and Greek armies repelled the Bulgarian offensive and counter-attacked into Bulgaria. Romania, who having taken no part in the conflict, had intact armies to strike with, invaded Bulgaria from the north in violation of a peace treaty between the two states. The Ottoman Empire also attacked Bulgaria and advanced in Thrace regaining Adrianople. In the resulting Treaty of Bucharest, Bulgaria lost most of the territories it had gained in the First Balkan War in addition to being forced to cede the ex-Ottoman south-third of Dobroudja province to Romania.[6]

Background

The background to the wars lies in the incomplete emergence of nation-states on the European territory of the Ottoman Empire during the second half of the 19th century. Serbia had gained substantial territory during the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878, while Greece acquired Thessaly in 1881 (although it lost a small area back to the Ottoman Empire in 1897) and Bulgaria (an autonomous principality since 1878) incorporated the formerly distinct province of Eastern Rumelia (1885). All three countries, as well as Montenegro, sought additional territories within the large Ottoman-ruled region known as Rumelia, comprising Eastern Rumelia, Albania, Macedonia, and Thrace.

Policies of the Great Powers

Throughout the 19th century, the Great Powers shared different aims over the "Eastern Question" and the integrity of the Ottoman Empire. Russia wanted access to the "warm waters" of the Mediterranean from the Black Sea; it pursued a pan-Slavic foreign policy and therefore supported Bulgaria and Serbia. Britain wished to deny Russia access to the "warm waters" and supported the integrity of the Ottoman Empire, although it also supported a limited expansion of Greece as a backup plan in case integrity of the Empire was no longer possible. France wished to strengthen its position in the region, especially in the Levant (today's Lebanon, Syria, the Palestinian territories and Israel).

Habsburg-ruled Austria-Hungary wished for a continuation of the existence of the Ottoman Empire, since both were troubled multinational entities and thus the collapse of the one might weaken the other. The Habsburgs also saw a strong Ottoman presence in the area as a counterweight to the Serbian nationalistic call to their own Serb subjects in Bosnia, Vojvodina and other parts of the empire. Italy, it has been argued, wished to recreate the Roman empire, though its primary aim at the time seems to have been the denial of access to the Adriatic Sea to another major sea power. The German Empire, in turn, under the "Drang nach Osten" policy, aspired to turn the Ottoman Empire into its own de facto colony, and thus supported its integrity.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Bulgaria and Greece contended for Ottoman Macedonia and Thrace. Ethnic Greeks sought the forced "Hellenization" of ethnic Bulgars, who sought "Bulgarization" of Greeks (Rise of nationalism). Both nations sent armed irregulars into Ottoman territory to protect and assist their ethnic kindred. From 1904, there was low intensity warfare in Macedonia between the Greek and Bulgarian bands and the Ottoman army (the Struggle for Macedonia). After the Young Turk revolution of July 1908, the situation changed drastically.

Young Turk Revolution

The 1908 Young Turk Revolution saw the reinstatement of constitutional monarchy in the Ottoman Empire and the start of the Second Constitutional Era. When the revolt broke out, it was supported by intellectuals, the army, and almost all the ethnic minorities of the Empire, and forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to re-adopt the long defunct Ottoman constitution of 1876 and parliament. Hopes were raised among the Balkan ethnicities of reforms and autonomy, and elections were held to form a representative, multi-ethnic, Ottoman parliament. However, following the Sultan's attempted counter-coup, the liberal element of the Young Turks was sidelined and the nationalist element became dominant.

At the same time, in October 1908, Austria-Hungary seized the opportunity of the Ottoman political upheaval to annex the de jure Ottoman province of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which it had occupied since 1878 (see Bosnian Crisis). Bulgaria declared independence as it had done in 1878, but this time the independence was internationally recognised. The Greeks of the autonomous Cretan State proclaimed unification with Greece, though the opposition of the Great Powers prevented the latter action from taking practical effect. It has large influence in the consequent world order.

Reaction in the Balkan States

Serbia was frustrated in the north by Austria-Hungary's incorporation of Bosnia. In March 1909, Serbia was forced to accept the annexation and restrain anti-Habsburg agitation by Serbian nationalists. Instead, the Serbian government (PM: Nikola Pašić) looked to formerly Serb territories in the south, notably "Old Serbia" (the Sanjak of Novi Pazar and the province of Kosovo).

On 15 August 1909 the Military League, a group of Greek officers, took action against the government to reform their country's national government and reorganize the army. The Military League found itself unable to create a new political system, until the League summoned the Cretan politician Eleutherios Venizelos to Athens as its political adviser. Venizelos persuaded king George I to revise the constitution and asked the League to disband in favor of a National Assembly. In March 1910 the Military League dissolved itself.[7]

Bulgaria, which had secured Ottoman recognition of her independence in April 1909 and enjoyed the friendship of Russia,[8] also looked to annex districts of Ottoman Thrace and Macedonia. In August 1910 Montenegro followed Bulgaria's precedent by becoming a kingdom.

Balkan League

Following Italy's victory in the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912, the Young Turks fell from power after a coup. The Balkan countries saw this as an opportunity to attack the Ottoman Empire and fulfill their desires of expansion.

With the initial encouragement of Russian agents, a series of agreements was concluded between Serbia and Bulgaria in March 1912. Military victory against the Ottoman Empire would not be possible while it could bring reinforcements from Asia. The condition of the Ottoman railways of the time was not advanced, so most reinforcements would have to come by sea through the Aegean Sea. Greece was the only Balkan country with a navy powerful enough to deny use of the Aegean to the Ottoman Empire, thus a treaty between Greece and Bulgaria became necessary; it was signed in May 1912.

Montenegro concluded agreements between Serbia and Bulgaria later that year. Bulgaria signed treaties with Serbia to divide the territory of northern Macedonia.

This alliance between Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Montenegro became known as the Balkan League; its existence was undesirable for all the Great Powers. The League was loose at best, though secret liaison officers were exchanged between the Greek and the Serbian army after the war began. Greece delayed the start of the war several times in the summer of 1912, to better prepare her navy, but Montenegro declared war on 8 October (25 September O.S.). Following an ultimatum to the Ottoman Empire, the remaining members of the alliance entered the conflict on 17 October.

First Balkan War

The three Slavic allies (Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro) had laid out extensive plans to coordinate their war efforts, in continuation of their secret prewar settlements and under close Russian supervision (Greece was not included). Serbia and Montenegro would attack in the theater of Sandjak, Bulgaria and Serbia in Macedonia and Thrace.

The Ottoman Empire's situation was difficult. Its population of about 26 million people provided a massive pool of manpower, but ¾ of the population and nearly all of the Muslim component lived in the Asian part of the Empire. Reinforcements had to come from Asia mainly by sea, which depended on the result of battles between the Turkish and Greek navies in the Aegean.

With the outbreak of the war, the Ottoman Empire activated three Army HQs: the Thracian HQ in Constantinople, the Western HQ in Salonika, and the Vardar HQ in Skopje, against the Bulgarians, the Greeks and the Serbians respectively. Most of their available forces were allocated to these fronts. Smaller independent units were allocated elsewhere, mostly around heavily fortified cities.

Montenegro was the first that declared war on 8 October[9] (25 September O.S.). Its main thrust was towards Shkodra, with secondary operations in the Novi Pazar area. The rest of the Allies, after giving a common ultimatum, declared war a week later. Bulgaria attacked towards Eastern Thrace, being stopped only at the outskirts of Constantinople at the Çatalca line and the isthmus of the Gallipoli peninsula, while secondary forces captured Western Thrace and Eastern Macedonia. Serbia attacked south towards Skopje and Monastir and then turned west to present-day Albania, reaching the Adriatic, while a second Army captured Kosovo and linked with the Montenegrin forces. Greece's main forces attacked from Thessaly into Macedonia through the Sarantaporo strait and after capturing Thessaloniki on 12 November (on 26 October 1912, O.S.) expanded its occupied area and linked up with the Serbian army to the northwest, while its main forces turned east towards Kavala, reaching the Bulgarians. Another Greek army attacked into Epirus towards Ioannina.[10]

In the naval front the Ottoman fleet twice exited the Dardanelles and was twice defeated by the Greek Navy, in the battles of Elli and Lemnos. Greek dominance on the Aegean Sea made it impossible for the Ottomans to transfer the planned troops from the Middle East to the Thracian (against the Bulgarian) and to the Macedonian (against the Greeks and Serbians) fronts.[11] According to the E.J. Erickson the Greek Navy also played a crucial, albeit indirect role, in the Thracian campaign by neutralizing no less than three Thracian Corps (see First Balkan War, the Bulgarian theater of operations), a significant portion of the Ottoman Army there, in the all-important opening round of the war.[11] After the defeating of the Ottoman fleet the Greek Navy was also free to liberate the islands of the Aegean.[12] General Nikola Ivanov identified the activity of the Greek Navy as the chief factor in the general success of the allies.[11][13]

In January, after a successful coup by young army officers, the Ottoman Empire decided to continue the war. After a failed Ottoman counter-attack in the Western-Thracian front, Bulgarian forces, with the help of the Serbian Army, managed to conquer Adrianople while Greek forces managed to take Ioannina after defeating the Ottomans in the battle of Bizani. In the joint Serbian-Montenegrin theater of operation, the Montenegrin army besieged and captured the Shkodra, ending the Ottoman presence in Europe west of the Çatalca line after nearly 500 years. The war ended officially with the Treaty of London on 30(17) May 1913.

Second Balkan War

Though the Balkan allies had fought together against the common enemy, that was not enough to overcome their mutual rivalries. In the original document for the Balkans league, Serbia promised Bulgaria most of Macedonia. But before the first war come to an end, Serbia (in violation of the previous agreement) and Greece revealed their plan to keep possession of the territories that their forces had occupied. This act prompted the tsar of Bulgaria to invade his allies. Moreover, during the First Balkan War[14](or disputably the Second Balkan War)[15] the Greek army burned altogether 161 Bulgarian villages and massacred thousands of inhabitants. The Second Balkan War broke out on 29(16) June 1913 when Bulgaria attacked its erstwhile allies in the First Balkan War, Serbia and Greece, while Montenegro and the Ottoman Empire intervened later against Bulgaria, with Romania attacking Bulgaria from the north. When the Greek army entered Thessaloniki in the First Balkan War ahead of the Bulgarian 7th division by only a day, they were asked to allow a Bulgarian battalion to enter the city. Greece accepted in exchange for allowing a Greek unit to enter the city of Serres.

The Bulgarian unit that entered Thessaloniki turned out to be a 18,000-strong division instead of the battalion, something which caused concern among the Greeks, who viewed it as a Bulgarian attempt to establish a condominium over the city. In the event, due to the urgently needed reinforcements in the Thracian front, Bulgarian Headquarters was soon forced to remove its troops from the city (while the Greeks agreed by mutual treaty to remove their units based in Serres) and transport them to Dedeağaç (modern Alexandroupolis), but still it left behind a battalion that started fortifying its positions.

Greece had also allowed the Bulgarians to control the stretch of the Thessaloniki-Constantinople railroad that lay in Greek-occupied territory, since Bulgaria controlled the largest part of this railroad towards Thrace. After the end of the operations in Thrace—and confirming Greek concerns—Bulgaria was not satisfied with the territory it controlled in Macedonia and immediately asked Greece to relinquish its control over Thessaloniki and the land north of Pieria, effectively handing over all Aegean Macedonia. These unacceptable demands, together with the Bulgarian refusal to demobilize its army after the Treaty of London had ended the common war against the Ottomans, alarmed Greece, which decided to also maintain its army's mobilization.

Similarly, in northern Macedonia, the tension between Serbia and Bulgaria due to later aspirations over Vardar Macedonia generated many incidents between the nearby armies, prompting Serbia to maintain its army's mobilization. Serbia and Greece proposed that each of the three countries reduce its army by one fourth, as a first step to facilitate a peaceful solution, but Bulgaria rejected it. Seeing the omens, Greece and Serbia started a series of negotiations and signed a treaty on 1 June(19 May) 1913. With this treaty, a mutual border was agreed between the two countries, together with an agreement for mutual military and diplomatic support in case of a Bulgarian or/and Austro-Hungarian attack. Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, being well informed, tried to stop the upcoming conflict on 8 June, by sending an identical personal message to the Kings of Bulgaria and Serbia, offering to act as arbitrator according to the provisions of the 1912 Serbo-Bulgarian treaty. But Bulgaria, by making the acceptance of Russian arbitration conditional, in effect denied any discussion and caused Russia to repudiate its alliance with Bulgaria (see Russo-Bulgarian military convention signed 31 May 1902).

The Serbs and the Greeks had a military advantage on the eve of the war because their armies confronted comparatively weak Ottoman forces in the First Balkan War and suffered relatively light casualties[16] while the Bulgarians were involved in heavy fighting in Thrace. The Serbs and the Greeks had time to fortify their positions in Macedonia. The Bulgarians also held some advantages, controlling internal communication and supply lines.[16]

On 29(16) June 1913 General Savov, under direct orders of Tsar Ferdinand I, issued attacking orders against both Greece and Serbia without consulting the Bulgarian government and without any official declaration of war.[17] During the night of 30(17) June 1913 they attacked the Serbian army at Bregalnica river and then the Greek army in Nigrita. The Serbian army resisted the sudden night attack, while most of soldiers did not even know who they were fighting with, as Bulgarian camps were located next to Serbs and were considered allies. Montenegro's forces were just a few kilometers away and also rushed to the battle. The Bulgarian attack was halted.

The Greek army was also successful.[16] It retreated according to plan for two days while Thessaloniki was cleared of the remaining Bulgarian regiment. Then the Greek army counter-attacked and defeated the Bulgarians at Kilkis (Kukush), after which the mostly Bulgarian town was destroyed and its population expelled.[18][19] Following the capture of Kilkis, the Greek army's pace was not quick enough to prevent the destruction of Nigrita, Serres, and Doxato and massacres of non-combatant Greek inhabitants at Demir Hisar and Doxato by the Bulgarian army.[20][21] The Greek army then divided its forces and advanced in two directions. Part proceeded east and occupied Western Thrace. The rest of the Greek army advanced up to the Struma River valley, defeating the Bulgarian army in the battles of Doiran and Mt. Beles, and continued its advance to the north towards Sofia. In the Kresna straits the Greeks were ambushed by the Bulgarian 2nd and 1st Army newly arrived from the Serbian front that had already taken defensive positions there following the Bulgarian victory at Kalimanci.

By 30 July the Greek army was outnumbered by the counter-attacking Bulgarian army, which attempted to encircle the Greeks in a Cannae-type battle, by applying pressure on their flanks.[22] The Greek army was exhausted and faced logistical difficulties. The battle was continued for 11 days, between 29 July and 9 August over 20 km of a maze of forests and mountains with no conclusion. The Greek King, seeing that the units he fought were from the Serbian front, tried to convince the Serbs to renew their attack, as the front ahead of them was now thinner, but the Serbs rejected it. By then, news came of the Romanian advance toward Sofia and its imminent fall. Facing the danger of encirclement, Constantine realized that his army could no longer continue hostilities, agreed to Eleftherios Venizelos' proposal and accepted the Bulgarian request for armistice as this had been communicated through Romania.

Romania had raised an army and declared war on Bulgaria on 10 July(27 June) as it had from 28(15) June officially warned Bulgaria that it would not remain neutral in a new Balkan war, due to Bulgaria's refusal to cede the fortress of Silistra as promised before the First Balkan war in exchange for Romanian neutrality. Its forces encountered little resistance and by the time the Greeks accepted the Bulgarian request for armistice they had reached Vrazhdebna, 7 miles from the center of Sofia.

Seeing the military position of the Bulgarian army the Ottomans decided to intervene. They attacked and finding no opposition, managed to recover eastern Thrace with its fortified city of Adrianople, regaining an area in Europe which was only slightly larger than the present-day European territory of the Republic of Turkey.

Reactions among the Great Powers during the wars

The developments that led to the First Balkan War did not go unnoticed by the Great Powers, but although there was an official consensus between the European Powers over the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire, which led to a stern warning to the Balkan states, unofficially each of them took a different diplomatic approach due to their conflicting interests in the area. As a result, any possible preventive effect of the common official warning was cancelled by the mixed unofficial signals, and failed to prevent or to stop the war:

- Russia was a prime mover in the establishment of the Balkan League and saw it as an essential tool in case of a future war against its rival, the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[23] But it was unaware of the Bulgarian plans over Thrace and Constantinople, territories on which it had long-held ambitions, and on which it had just secured a secret agreement of expansion from its allies France and Britain, as a reward for participating in the upcoming Great War against the Central Powers.

- France, not feeling ready for a war against Germany in 1912, took a totally negative position against the war, firmly informing its ally Russia that it would not take part in a potential conflict between Russia and Austria-Hungary if it resulted from the actions of the Balkan League. The French however failed to achieve British participation in a common intervention to stop the Balkan conflict.

- The British Empire, although officially a staunch supporter of the Ottoman Empire's integrity, took secret diplomatic steps encouraging Greek entry into the League in order to counteract Russian influence. At the same time it encouraged Bulgarian aspirations over Thrace, preferring a Bulgarian Thrace to a Russian one, despite the assurances the British had given to the Russians in regard to their expansion there.

- Austria-Hungary, struggling for a port on the Adriatic and seeking ways for expansion in the south at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, was totally opposed to any other nation's expansion in the area. At the same time, the Habsburg empire had its own internal problems with significant Slav populations that campaigned against German-Hungarian control of the multinational state. Serbia, whose aspirations in the direction of Austrian-held Bosnia were no secret, was considered an enemy and the main tool of Russian machinations that were behind the agitation of Austria's Slav subjects. But Austria-Hungary failed to secure German backup for a firm reaction. Initially, Emperor Wilhelm II told the Archduke Franz Ferdinand that Germany was ready to support Austria in all circumstances—even at the risk of a world war, but the Austro-Hungarians hesitated. Finally, in the German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912 the consensus was that Germany would not be ready for war until at least mid-1914 and passed notes to that effect to the Habsburgs. Consequently, no actions could be taken when the Serbs acceded to the Austrian ultimatum of 18 October and withdrew from Albania.

- Germany, already heavily involved in internal Ottoman politics, officially opposed a war against the Empire. But in her effort to win Bulgaria for the Central Powers, and seeing the inevitability of Ottoman disintegration, was toying with the idea of replacing the Balkan area of the Ottomans with a friendly Greater Bulgaria in her San Stefano borders—an idea that was based on the German origin of the Bulgarian King and his anti-Russian sentiments.

The Second Balkan war was a catastrophic blow to Russian policies in the Balkans, where Russia had focused its interests for access to the "warm seas" for centuries. First, it marked the end of the Balkan League, a vital arm of the Russian system of defense against Austria-Hungary. Second, the clearly pro-Serbian position Russia had been forced to take in the conflict, mainly due to Bulgaria's uncompromising aggressiveness, caused a permanent break-up between the two countries. Accordingly, Bulgaria reverted its policy to one closer to the Central Powers' understanding over an anti-Serbian front, due to its new national aspirations, now expressed mainly against Serbia. As a result, Serbia was isolated militarily against its rival Austria-Hungary, a development that eventually doomed Serbia in the coming war a year later. But most damaging, the new situation effectively trapped Russian foreign policy: After 1913, Russia could not afford losing its last ally in this crucial area and thus had no alternatives but to unconditionally support Serbia when the crisis between Serbia and Austria broke out in 1914. This was a position that inevitably drew her, although unwillingly, into a World War with devastating results for her, since she was less prepared (both militarily and socially) for that event than any other Great Power.

Austria-Hungary took alarm at the great increase in Serbia's territory at the expense of its national aspirations in the region, as well as Serbia's rising status, especially to Austria-Hungary's Slavic populations. This concern was shared by Germany, which saw Serbia as a satellite of Russia. This contributed significantly to the two Central Powers' willingness to go to war as soon as possible.

Finally, when a Serbian backed organization assassinated the heir of the Austro-Hungarian throne, causing the 1914 July Crisis, nobody could stop the conflict and the First World War broke out.

Aftermath

Soviet demographer Boris Urlanis estimated in Voini I Narodo-Nacelenie Europi (1960) that in the first and second Balkan wars there were 122,000 killed in action, 20,000 dead of wounds, and 82,000 dead of disease.

Battles of the Balkan Wars

First Balkan War

Serbian-Ottoman Battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Kumanovo | 1912 | Radomir Putnik | Zeki Pasha | Serbian Victory |

| Battle of Prilep | 1912 | Petar Bojović | Zeki Pasha | Serbian Victory |

| Battle of Monastir | 1912 | Petar Bojović | Zeki Pasha | Serbian Victory |

| Siege of Scutari | 1913 | King Nikola | Hasan Pasha | Montenegrin-Serb Victory |

| Siege of Adrianople | 1913 | Stepa Stepanovic | Gazi Pasha | Bulgarian-Serbian Victory |

Bulgarian-Ottoman Battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Kardzhali | 1912 | Vasil Delov | Mehmed Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Kirk Kilisse | 1912 | Radko Dimitriev | Mahmut Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Lule Burgas | 1912 | Radko Dimitriev | Abdullah Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Merhamli | 1912 | Nikola Genev | Mehmed Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Kaliakra | 1912 | Dimitar Dobrev | Hüseyin Bey | Bulgarian Victory |

| First Battle of Çatalca | 1912 | Radko Dimitriev | Nazim Pasha | Ottoman Victory |

| Battle of Bulair | 1913 | Georgi Todorov | Fethi Bey | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Şarköy | 1913 | Stiliyan Kovachev | Enver Bey | Bulgarian Victory |

| Siege of Adrianople | 1913 | Georgi Vazov | Gazi Pasha | Bulgarian-Serbian Victory |

| Second Battle of Çatalca | 1913 | Vasil Kutinchev | Ahmet Pasha | Indecisive |

Greek-Ottoman Battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Sarantaporo | 1912 | Constantine I | Hasan Pasha | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Yenidje | 1912 | Constantine I | Hasan Pasha | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Pente Pigadia | 1912 | Sapountzakis | Esat Pasha | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Sorovich | 1912 | Matthaiopoulos | Hasan Pasha | Ottoman Victory |

| Revolt of Himara | 1912 | Spyromilios | Esat Pasha | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Driskos | 1912 | Esat Pasha | Ottoman Victory | |

| Battle of Elli | 1912 | Kountouriotis | Remzi Bey | Greek Victory |

| Capture of Korytsa | 1912 | Damianos | Davit Pasha | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Lemnos | 1913 | Sapountzakis | Remzi Bey | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Bizani | 1913 | Constantine I | Esat Pasha | Greek Victory |

Second Balkan War

Bulgarian-Serbian Battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Bregalnica | 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Radomir Putnik | Serbian Victory |

| Battle of Knjaževac | 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Radomir Putnik | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Kalimanci | 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Radomir Putnik | Bulgarian Victory |

| Siege of Vidin | 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Radomir Putnik | Indecisive |

| Battle of Pirot | 1913 | Mihail Savov | Stepa Stepanovic | Serbian Victory |

Bulgarian-Greek Battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Kilkis–Lachanas | 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Constantine I | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Doiran | 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Constantine I | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Kresna Gorge | 1913 | Mihail Savov | Constantine I | Stalemate |

Bulgarian-Ottoman Battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Battle of Adrianople | 1913 | Mihail Savov | Enver Pasha | Ottoman Victory |

See also

Since the area has been referred to as the Balkans, notable conflicts have included the following:

- The Ottoman wars in Europe

- The Serbo-Bulgarian War (1885)

- The Albanian Revolt of 1910

- The Albanian Revolt of 1912

- The Balkans Campaign (World War I)

- The Balkans Campaign (World War II)

- The Yugoslav wars (1991–1999)

- List of places burned during the Balkan Wars

Trivia

- Members of Beşiktaş J.K. fought in the war for the defense of the Ottoman Empire. The club's colors, which were originally red and white were changed to black and white following the heavy loss of the territories as a sign of mourning.

Notes

- ^ Edward J. Erickson, Defeat in Detail, The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913, Westport, Praeger, 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Christopher Clark (2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins. pp. 45, 559.

- ^ Richard C. Hall, The Balkan Wars 1912–1913: Prelude to the First World War (2000)

- ^ Ernst C. Helmreich, The diplomacy of the Balkan wars, 1912–1913 (1938)

- ^ Richard C. Hall, The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: Prelude to the First World War (2000) online

- ^ "The World Crisis, 1911–1918" by Winston Churchill, https://books.google.com/books?id=6l6Fgnz8fXIC, 1931 Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 278

- ^ "Military League", Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ "THE BALKAN WARS". US Library of Congress. 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ Hall, Richard. 1914-1918 Online: International Encyclopedia of the First World War http://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/balkan_wars_1912-1913. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Balkan Wars Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ a b c Erickson 2003, p. 333

- ^ "History of Greece" Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ Hall 2000, p. 65

- ^ {fDespot, Igor. The Balkan Wars in the Eyes of the Warring Parties: Perceptions and Interpretations.

- ^ Targeting civilians in war; Alexander B. Downes; 2008; [https://books.google.com/books?id=TWEEW8SBvEAC&lpg=PT30&dq=%22second%20balkan%20war%22%20greeks%20massacres&pg=PT30#v=onepage&q=%22second%20balkan%20war%22%20greeks%20massacres&f=false p.35

- ^ a b c Hall 2000, p. 117

- ^ George Phillipov (Winter 1995). "THE MACEDONIAN ENIGMA". Magazine: Australia &World Affairs,. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Hugh Poulton, "Who are the Macedonians?", 2000, p.75

- ^ "Balkan Forum", Volume 5, Issues 1–2, 1997, p.132

- ^ Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars, published by the Endowment Washington, D.C. 1914, p. 97-99 pp.79–95

- ^ The Great Events by Famous Historians, Charles F. Horne, 2006, ISBN 978-1-4264-4107-3, p. 420

- ^ Hall, Richard (2000). The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: Prelude to the First World War. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 0-415-22946-4.

- ^ Stowell, Ellery Cory (2009). The Diplomacy Of The War Of 1914: The Beginnings Of The War (1915). Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-104-48758-4.

Further reading

- Clark, Christopher (2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins.

- Erickson, Edward J. Defeat in Detail, The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Praeger. (2003) ISBN 0275978885 OCLC 845518305 Available as an e-book. ISBN 0313051798 OCLC 57426266

- Gerolymatos, André. The Balkan wars: conquest, revolution, and retribution from the Ottoman era to the twentieth century and beyond. Basic Books (2002) ISBN 0465027326 OCLC 49323460

- Hall, Richard C. The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: Prelude to the First World War. Routledge. (2000) online ISBN 0-415-22947-2 OCLC 45144367

- Helmreich, Ernst C. The diplomacy of the Balkan wars, 1912–1913. Harvard University Press.(1938) OCLC 3819108 Reprinted in 1969 by Russell. OCLC 847291378

- Macmillan, Margaret. The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (2013) ch 16 excerpt and text search

- Winston Churchill. "The World Crisis, 1911–1918" , (1931) https://books.google.com/books?id=6l6Fgnz8fXIC, pp. 278

External links

- U.S. State Department. "The Formation of the Balkan Alliance of 1912" (1918)

- Project Gutenberg's The Balkan Wars: 1912–1913, by Jacob Gould Schurman

- US Library of Congress in the Balkan Wars

- The Balkan crises, 1903–1914.]

- Balkan Wars from a Turkish perspective

- Wikisource: The New Student's Reference Work/The Balkans and the Peace of Europe

- Historic films about the Balkan Wars at europeanfilmgateway.eu