The War of the Worlds (1953 film)

| The War of the Worlds | |

|---|---|

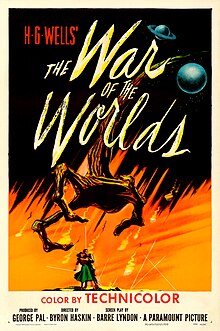

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Byron Haskin |

| Screenplay by | Barré Lyndon |

| Based on | The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells |

| Produced by | George Pal |

| Starring | Gene Barry Ann Robinson |

| Cinematography | George Barnes |

| Edited by | Everett Douglas |

| Music by | Leith Stevens |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release dates | |

Running time | 85 minutes[3] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million |

| Box office | $2 million (US rentals)[4] |

The War of the Worlds (also known in promotional material as H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds) is a 1953 American science fiction thriller film directed by Byron Haskin, produced by George Pal, and starring Gene Barry and Ann Robinson. It is the first of several feature film adaptations of H. G. Wells' 1898 novel of the same name. The setting is changed from Victorian era England to 1953 Southern California. Earth is suddenly invaded by Martians, and American scientist Doctor Clayton Forrester searches for any weakness to stop them.

The War of the Worlds won the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects and went on to influence other science fiction films. In 2011, it was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the United States Library of Congress, who deemed it "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

[edit]A large object crashes near the small town of Linda Rosa, California. At the impact site, Dr. Clayton Forrester, an atomic scientist, investigates. He meets Sylvia Van Buren and her uncle, Pastor Collins. Together, they attend an evening square dance. Back at the crash site, a hatch on the object unscrews and falls away. As three men standing guard attempt to make contact waving a white flag, a heat-ray obliterates them. U.S. Marines later surround the site, as reports pour in of more cylinders, presumably from Mars, landing all over Earth, destroying cities. Three war machines now emerge from the Linda Rosa cylinder. Pastor Collins attempts contact but is disintegrated. Marines open fire, but are unable to penetrate the invaders' force field. The aliens counterattack with death ray weaponry, sending the Marines into full retreat. Air Force attack jets follow up, but they are annihilated.

Forrester and Sylvia escape in a small plane but later crash land. Hiding in a nearby empty farmhouse, they are nearly buried by yet another crashing cylinder. A long cable with an electronic eye explores the house, but Forrester severs the eye with an axe. Later, an alien creature enters and approaches Sylvia but retreats when Forrester wounds it. He collects its blood on a cloth. Then, they escape just before the farmhouse is destroyed by a heat-ray. Forrester takes the electronic eye and blood sample to his team of scientists at a Los Angeles university, hoping to find a way to defeat the invaders. The colleagues examine the sample and discover the visitors' blood is extremely anemic. Meanwhile, as the world's capitals fall to the invaders, experts predict total world domination in just weeks. The U.S. government thus authorizes use of the atom bomb. However, it proves ineffective, and the aliens continue their advance on Los Angeles. During the city's chaotic evacuation, Forrester, Sylvia, and the other scientists become separated.

Stranded in Los Angeles, Forrester seeks Sylvia. Based on a story she told him earlier, he guesses she has taken refuge in a church. After searching through several, he finds Sylvia among many praying survivors. Just as the invaders attack near the church, their machines lose power and crash. As Forrester sees one of the aliens die, he reflects, "We were all praying for a miracle." He and other survivors look heavenward. An off-screen narrator explains that the aliens had "no resistance to the bacteria in our atmosphere to which we have long since become immune [and] which God in His wisdom had put upon this earth."

Cast

[edit]- Gene Barry as Doctor Clayton Forrester

- Ann Robinson as Sylvia Van Buren

- Les Tremayne as Major General Mann

- Bob Cornthwaite as Doctor Pryor

- Sandro Giglio as Doctor Bilderbeck

- Lewis Martin as The Reverend Doctor Matthew Collins

- Housely Stevenson Jr. as General Mann's aide

- Paul Frees as Radio reporter/pre-titles narrator

- Bill Phipps as Wash Perry

- Vernon Rich as Colonel Ralph Heffner

- Henry Brandon as Cop at crash

- Jack Kruschen as Salvatore

- Sir Cedric Hardwicke as post-titles narrator

Production

[edit]

The War of the Worlds opens with a black-and-white prologue featuring newsreel war footage and a voice-over by Paul Frees that describes the destructive technological advancements of Earthly warfare from World War I through World War II. The image then smash cuts to vivid Technicolor and the dramatic opening title card and credits. The story begins with a series of color matte paintings by astronomical artist Chesley Bonestell that depict the planets of our Solar System, except Venus, about which little was known at the time. A narrator (Sir Cedric Hardwicke) tours the hostile environment of each world, eventually explaining to the audience why the Martians find our lush green and blue Earth the only world worthy of their scrutiny and coming invasion.[5][6]

Paramount Pictures first attempted to adapt The War of the Worlds when the studio bought the film rights to the novel in 1925. Ray Pomeroy began working on an outline with Cecil B. DeMille planned as director, but the project was put into turn-around. Later in the 1930s, Paramount assigned Sergei Eisenstein to direct an adaptation of the novel under his contract with the studio but failed to produce a film. Alfred Hitchcock also entered discussions about adapting the novel with Wells and Gaumont-British may have optioned the rights, but the project did not go forward. Alexander Korda also expressed interest in adapting the novel.[7]

The film finally began moving forward after George Pal was assigned to the project in July 1951. Pal originally envisioned a film more faithful to the source material in which a scientist would search for his wife after the invasion destroyed society, but Paramount Pictures production head Don Hartman demanded changes including a romantic subplot in which the scientist would meet and fall in love with a woman.[7] This is the first of two adaptations of Wells's classic science fiction filmed by Pal. It is considered one of the great science fiction films of the 1950s.[8]

Lee Marvin was considered as the protagonist before Gene Barry was cast. Jim Meservy, Dan Dowling, Abdullah Abbas, and the Mitchell Choir Boys were also considered for casting but later cut.

Pal had planned for the final third of the film to be shot in the new 3D process to visually enhance the Martians' attack on Los Angeles. The plan was dropped before production began. World War II stock footage was used to produce a montage of destruction to show the worldwide invasion, with armies of all nations joining together to fight the invaders.[6]

Dr. Forrester's and the other scientists' Pacific Tech (Pacific Institute of Science and Technology, represented by buildings on the Paramount studio lot) has since been part of other films and television episodes when it was decided to include a scientific California university without using the name of a real one.[5]

Location shooting took place in Corona, California, which stood in for the fictitious town of Linda Rosa. St. Brendan's Catholic Church, at 310 South Van Ness Avenue in Los Angeles, was the setting for the climactic scene in which a large group of desperate people gather to pray. The rolling hills and main thoroughfares of El Sereno, Los Angeles, were also used in the film.[5]

On the commentary track of the 2005 Special Collector's DVD Edition of War of the Worlds, Robinson and Barry say that the cartoon character Woody Woodpecker is in a treetop, center screen, when the first large Martian meteorite-ship crashes through the sky, near the beginning of the film. George Pal and Woody's creator, Walter Lantz, were close friends. Pal tried always to include Woody out of friendship and for good luck in his productions. Joe Adamson wrote years later: "Walter had been close friends with Pal ever since Pal had left Europe in advance of the war and arrived in Hollywood".[9]

The prototype Northrop YB-49 Flying Wing is prominently featured in the atomic-bombing sequence. Pal and Haskin incorporated Northrop color footage of a YB-49 test flight, originally used in Paramount's Popular Science theatrical shorts, to show the Flying Wing's takeoff and bomb run.[10]

Differences from the Wells novel

[edit]Caroline Blake has written that the film is very different from the original novel in its attitude toward religion, as reflected especially in the depiction of clergymen. "The staunchly secularist Wells depicted a cowardly and thoroughly uninspiring Curate, whom the narrator regards with disgust, with which the reader is invited to concur. In the film, there is instead the sympathetic and heroic Pastor Collins who dies a martyr's death. And then the film's final scene in the church, strongly emphasizing the Divine nature of Humanity's deliverance, has no parallel in the original book."[11]

Pal's adaptation has many other differences from H. G. Wells's novel. The closest resemblance is probably that of the antagonists. The film's aliens are indeed Martians and invade Earth for the same reasons as those stated in the novel. The state of Mars suggests that it is becoming unable to support life, leading to the Martians' decision to try to make Earth their new home. They land in the same way, by crashing to Earth. The novel's spacecraft, however, are large, cylindrical projectiles fired from the Martian surface from a cannon, instead of the film's meteorite-spaceships; but the Martians emerge from their craft in the same way, by unscrewing a large, round hatch. They appear to have no use for humans in the film. In the novel, however, the invaders are observed "feeding" on humans by fatally transfusing their captives' blood supply directly into Martian bodies through pipettes. There is later speculation about the Martians' eventually using trained human slaves to hunt down all remaining survivors after they conquer Earth. In the film, the Martians do not bring their fast-growing red weed with them, but they are defeated by Earth microorganisms, as in the novel. However, they die from the effects of the microorganisms within three days of the landing of the first meteorite-ship; in the novel, the Martians die within about three weeks of their invasion of England.[6]

The film's Martians bear no physical resemblance to those of the novel, who are described as bear-sized, roundish creatures with grayish-brown bodies, "merely heads", with quivering beak-like, V-shaped mouths dripping saliva. They have sixteen whip-like tentacles in two groupings of eight arranged on each side of their mouths and two large "luminous, disk-like eyes". Because of budget constraints, their film counterparts are short, reddish-brown creatures with two long, thin arms with three long, thin fingers with suction-cup tips. The Martian head is a broad "face" at the top-front of its broad-shouldered upper torso, the only apparent feature of which is a single, large eye with three distinctly colored lenses of red, blue, and green. The Martians' lower extremities are never shown. Some speculative designs suggest three thin legs resembling their fingers, and others show them as bipeds with short, stubby legs with three-toed feet.[6]

The film's Martian war machines are more like those of the book than they first seem. The novel's war machines are 10-story-tall fast-moving tripods made of glittering metal, each with a "brazen hood" atop the body, moving "to and fro" as the machine moves. A heat-ray projector on an articulated arm is connected to the front of each machine's main body. However, the film's war machines are shaped like manta rays, with a bulbous, elongated green window at the front, through which the Martians observe their surroundings. On top of the machine is the cobra-like head heat-ray attached to a long, narrow, goose-neck extension, which can fire in any direction. They can be mistaken for flying machines, but Forrester states that they are lifted by invisible legs. One scene when the first war machine emerges has faint traces of three "energy legs" beneath that leave three sparking traces where they touch the burning ground, so they are tripods, though they are never so called. Whereas the novel's machines have no protection against the British army and navy cannon fire, the film's war machines have a force field surrounding them, described by Forrester as a "protective blister".[6]

The Martian weaponry is also partially unchanged. The heat-ray has the very same effect as that of the novel. However, the novel's heat-ray mechanism is briefly described as just a rounded hump when its silhouette rises above the landing crater's rim; it fires an invisible energy beam in a wide arc while still in the pit made by the first Martian cylinder after it crash-lands. The film's first heat-ray scene has a projector shaped like a cobra head with a single, red pulsing light, which likely acts as a targeting telescope for the Martians inside their war machine shaped like a manta ray. The novel describes another weapon, the "black smoke" used to kill all life; the war machines fire canisters containing a black smoke-powder through a bazooka-like tube accessory. When dispersed, this black powder is lethal to all life forms who breathe it. This weapon is replaced in the film by a Martian "skeleton beam" of green pulsing energy bursts fired from the wingtips of the manta-ray machines; these bursts break apart the sub-atomic bonds that hold matter together. These beams are used off-screen to obliterate several French cities.[6]

The plot of the film is very different from the novel, which tells the story of a 19th-century writer (with additional narration in later chapters by his medical-student younger brother) who journeys through Victorian London and its southwestern suburbs while the Martians attack, eventually being reunited with his wife; the film's protagonist is a Californian scientist who falls in love with a former college student after the Martian invasion begins. However, certain points of the film's plot are similar to the novel, from the crash-landing of the Martian meteorite-ships to their eventual defeat by Earth's microorganisms. Forrester also experiences similar events to the book's narrator, with an ordeal in a destroyed house, observing an actual Martian up close, and eventually reuniting with his love interest at the end of the story. The film has more of a Cold War theme with the atomic bomb against the invading enemy and the mass destruction that such a global war would inflict on humanity.[6]

Special effects

[edit]

An effort was made to avoid the stereotypical flying saucer look of UFOs. The Martian war machines were designed by Albert Nozaki with a sinister manta ray shape floating above the ground. Three Martian war machine props were made of copper. The same blueprints were used a decade later (without neck and cobra head) to construct the alien spacecraft in the film Robinson Crusoe on Mars, also directed by Byron Haskin. That prop was reportedly melted for a scrap copper recycling drive.[6]

Each Martian machine is topped with an articulated metal neck and arm, culminating in the cobra head heat ray projector, housing a single electronic eye that operates both as a periscope and as a weapon. The electronic eye houses a heat ray, which pulses and fires red sparking beams, all accompanied by thrumming and a high-pitched clattering shriek when the ray was used. The distinctive sound effect of the weapon was created by an orchestra performing a written score, mainly with violins and cellos. For many years, it was utilized as a standard ray-gun sound on children's television shows and the science-fiction anthology series The Outer Limits, particularly in the episode "The Children of Spider County".[5]

The machines also fire a pulsing green ray (referred to in dialog as "a skeleton beam") from their wingtips, generating a distinctive sound and disintegrating their targets. This second weapon is a replacement for the chemical weapon black smoke described in Wells's novel. Its sound effect (created by striking a high tension cable with a hammer) was reused in Star Trek: The Original Series, accompanying the launch of photon torpedoes. The sound when the Martian ships begin to move was also reused by Star Trek as the sound of an overloading hand phaser. Another prominent sound effect is a chattering, synthesized echo, perhaps representing some kind of Martian sonar sounds like hissing electronic rattlesnakes.[5]

When the large Marine force opens fire on the Martians with everything in its heavy arsenal, each Martian machine is protected by an impenetrable force field that resembles, when briefly visible between explosions, the clear jar placed over a mantle clock, or a bell jar with a cylindrical shape and a hemispherical top. This effect was accomplished with simple matte paintings on clear glass, which were then photographed and combined with other effects, and optically printed together during post-production.[6] While conventional Earth weapons cannot penetrate the electromagnetic shields, the Martian death ray weapons can fire through the shields against their targets without trouble.

The disintegration effect took 144 separate matte paintings to create. The sound effects of the war machines' heat rays firing were created by mixing the sound of three electric guitars being recorded backwards. The Martian's scream in the farmhouse ruins was created by mixing the sound of a microphone scraping along dry ice being combined with a woman's recorded scream and then reversed.[5]

There were many problems trying to create the walking tripods of Wells's novel. It was eventually decided to make the Martian machines appear to float in the air on three invisible legs. To visualize them, subtle special effects of downward lights were to be added directly under the moving war machines; however, in the final film, these only appear when one of the first machines can be seen rising from the Martian's landing site. It proved too difficult and dangerous to mark out the invisible legs while smoke and other effects must remain visible beneath the machines, and the effect also created a major fire hazard. In all of the subsequent scenes, however, the three invisible leg beams create small, sparking fires where they touch the ground.[5]

Quality of special effects

[edit]For 50 years, from the late 1960s when The War of the Worlds 3-strip Technicolor prints were replaced by the easier-to-use and less expensive Eastman Color stock, the quality of the film's special effects suffered dramatically. This degraded the lighting, timing, and image resolution, causing the original invisible overhead wires suspending the Martian war machines to become increasingly visible with each succeeding film and video format change. This led many, including respected critics, to mistakenly believe the effects were originally of low quality.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21]

Reception

[edit]Release

[edit]The official Hollywood premiere of The War of the Worlds was on February 20, 1953, although it did not go into general theatrical release until late that year.[6] The film was both a critical and box-office success. The film accrued $2,000,000 in distributors' domestic (U.S. and Canada) rentals, making the film the year's biggest science fiction hit. ("Rentals" refers to the distributor and studio's share of the box-office gross, which, according to Gebert, is roughly half of the money generated by ticket sales.)[22]

On its 1953 release, The War of the Worlds was rated X by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) for its alarming and "horrific" content, meaning no one under 16 could see the film. This was unsuccessfully protested by several local authorities, believing the rating should be lower. In 1961, Paramount Pictures sought to have the film's certificate reduced to A, meaning persons under 16 could view the film if accompanied by an adult, but this was rejected. The film was reclassified A in 1981, now meaning that the film may be unsuitable to under 14s. For its 1986 VHS release, The War of the Worlds was re-rated PG (meaning all audiences can see it but some scenes may be unsuitable for young children). It is an unusual example of a film that has was once rated X but now stands as a PG.[23][24]

Critical reaction

[edit]In The New York Times, A. H. Weiler's review commented: "[The film is] an imaginatively conceived, professionally turned adventure, which makes excellent use of Technicolor, special effects by a crew of experts, and impressively drawn backgrounds ... Director Byron Haskin, working from a tight script by Barré Lyndon, has made this excursion suspenseful, fast and, on occasion, properly chilling".[25] "Brog" in Variety said, "[It is] a socko science-fiction feature, as fearsome as a film as was the Orson Welles 1938 radio interpretation ... what starring honors there are go strictly to the special effects, which create an atmosphere of soul-chilling apprehension so effectively [that] audiences will actually take alarm at the danger posed in the picture. It can't be recommended for the weak-hearted, but to the many who delight in an occasional good scare, it's socko entertainment of hackle-raising quality".[26][27] The Monthly Film Bulletin of the UK called it "the best of the postwar American science-fiction films; the Martian machines have a quality of real terror, their sinister apparitions, prowlings and pulverisings are spectacularly well done, and the scenes of panic and destruction are staged with real flair".[28] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post called it "to put it gently, terrific", and "for my money, the King Kong of its day".[29]

The War of the Worlds won a Special Achievement Award from the Academy for its Visual Effects, as there was no competitive category that year. Everett Douglas was nominated for Film Editing, and the Paramount Studio Sound Department and Loren L. Ryder were nominated for Sound Recording.[30]

The War of the Worlds still receives high acclaim from some critics. On the film review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, it has a 90% rating based on 39 critics, with an average rating of 7.20/10. The consensus states: "Though it's dated in spots, The War of the Worlds retains an unnerving power, updating H. G. Wells's classic sci-fi tale to the Cold War era and featuring some of the best special effects of any 1950s film".[31]

4K restoration

[edit]In 2018, a new, fully restored 4K Dolby Vision transfer from the original three-strip Technicolor negatives was published on iTunes.[32] In July 2020, the film was reissued on Blu-ray and DVD by The Criterion Collection in the United States using the same 4K remaster and restoration. The Blu-ray documentation says the transfer process and careful color and contrast calibrations allowed the special effects to be restored to Technicolor release print quality, without the war machine's supporting wires.[33][34]

Legacy

[edit]The War of the Worlds was deemed culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant in 2011 by the United States Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry.[35] The Registry noted the film's release during the early years of the Cold War and how it used "the apocalyptic paranoia of the atomic age".[36] The Registry also cited the special effects, which at its release were called "soul-chilling, hackle-raising, and not for the faint of heart".[36]

The Martians were ranked the 27th best villains in the American Film Institute's list AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains.

The 1988 War of the Worlds TV series is a sequel to the Pal film. Ann Robinson reprises her role as Sylvia Van Buren in three episodes. Robinson also reprises her role in two other films, first as Dr. Van Buren in 1988's Midnight Movie Massacre and then as Dr. Sylvia Van Buren in 2005's The Naked Monster.[37]

The 1996 film Independence Day has several allusions to Pal's 1953 War of the Worlds. The failed attempt of a dropped atomic bomb is replaced with a nuclear-armed cruise missile launched by a B-2 Spirit bomber (a direct descendant of the Northrop YB-49 bomber in the 1953 film) and Captain Hiller being based in El Toro, California, which Dr. Forrester mentions as the home of the Marines, which make the first assault on the invading Martians in Pal's film.[38]

The Asylum's 2005 direct-to-DVD H. G. Wells' War of the Worlds has mild references to the Pal version. The Martian's mouth has three tongues that closely resemble the three Martian fingers in the Pal film. The Asylum film has scenes of power outages after the aliens' arrival via meteorite-ships. As in the Pal film, refugees hide in the mountains, instead of hiding underground as in the Wells novel, and the protagonist actively tries to fight the aliens by biological means.[39]

Steven Spielberg's 2005 version, War of the Worlds, although an adaptation of the Wells novel, has several references to the 1953 film. Gene Barry and Ann Robinson have cameo appearances near the end, and the invading aliens have three-fingered hands but are reptilian, walking tripods. A long, snaking, alien camera probe is deployed by the invaders.[40] In his 2018 film Ready Player One, Spielberg included a fallen Martian war machine more akin to the 1953 film.[41]

Tomohiro Nishikado, creator of the breakthrough 1978 video game Space Invaders, stated that seeing the film in childhood was one of the inspirations for the inclusion and the design of the aliens in the game.[42]

Mystery Science Theater 3000 named one of its lead characters, the mad scientist Dr. Clayton Forrester, as an homage to the 1953 film.[43]

In 2004, War of the Worlds was presented with a Retrospective Hugo Award for 1954 in the category of Best Dramatic Presentation — Short Form (works running 90 minutes or less).[44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "London Amusements". Daily Mirror. April 2, 1953. p. 15.

- ^ "The War of the Worlds - Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ "'The War of the Worlds'." British Board of Film Classification, March 9, 1953. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ 'The Top Box Office Hits of 1953', Variety, January 13, 1954

- ^ a b c d e f g Warren 1982, pp. 151–163.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rubin 1977, pp. 4–16, 34–47.

- ^ a b "The War of the Worlds". AFI Catalog. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Booker 2010, p. 126.

- ^ Adamson, Joe. 1985' [page needed]

- ^ Howe, Tom. "Northrop YB-49 Flying Wing." cedmagic.com. Retrieved: 25 August 2012.

- ^ Caroline G. Blake, Religion in Speculative Fiction, Ch.2, 5

- ^ Miller, Thomas Kent. Mars in the Movies: A History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016. ISBN 978-0-7864-9914-4. pp. 149-153 ISBN 978-0-7864-9914-4. pp. 149-153

- ^ John Brosnan’s Future Tense: “Unfortunately these wires are often visible on the screen, particularly during the sequence when the war machines first emerge from their crater and engage the army in battle.” Brosnan, John. Future Tense: The Cinema of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1978. p. 91

- ^ Phil Hardy’s The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Science Fiction: “Not all Jennings’ spectacular special effects work well—on their first appearance the Martian war machines have an obvious network of wires surrounding them.” Hardy, Phil (Ed.). The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Science Fiction. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Books, 1994. p. 143

- ^ John Clute’s and Peter Nicholls’ The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: “The wires holding up the machines are too often visible.” Clute, John, and Peter Nicholls (Eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993. p. 1300

- ^ Gary Gerani’s Top 100 Sci-Fi Movies: "While those cables holding up the machines are painfully visible, viewers tend to cut pre-digital fx a good deal of slack." Gerani, Gary. Top 100 Sci-Fi Movies. San Diego: IDW Publishing, 2011 p. 129

- ^ Barry Forshaw’s The War of the Worlds (BFI): “[I]t has to do be said that [the use of wires] is one of the most dated elements of the special-effects, as they are all too clearly visible in many sequences of the film.... In British showings of the film (when it was re-released in a curious late-1960s US/UK double bill with Hitchcock’s Psycho [1960]), the more sophisticated audiences of the day chuckled at these antediluvian special-effects.” Forshaw, Barry. The War of the Worlds. London: British Film Institute/Palgrave MacMillan, 2014. p. 152

- ^ Time, Inc.’s Special magazine publication, LIFE—Science Fiction: 100 Years of Great Movies, Vol. 16, No. 9, June 24, 2016: “The movie cost $2 million, and its $1.4 million worth of special effects remains, despite visible wires, impressive even in an age of CGI.” Time, Inc.’s Special magazine publication, LIFE—Science Fiction: 100 Years of Great Movies, Vol. 16, No. 9, June 24, 2016: p. 16

- ^ Peter Nicholls’ (Ed.) first edition of The Science Fiction Encyclopedia: “The first appearance of the war machines, after an impressive build-up of suspense, is spoilt by the obvious maze of wires supporting each one.” Nicholls, Peter. The Science Fiction Encyclopedia. New York: Doubleday; 1st edition, 1979)

- ^ C.J Henderson’s The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies: From 1897 to the Present: “Wells’ unique walking tripods are replaced by ordinary spaceship-like designs that move on beams of light. This wouldn’t be so bad if the wires holding them up weren’t visible in many scenes.” Henderson, C. J. Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies: From 1897 to the Present. New York: Checkmark Books, 2001.

- ^ Leonard Maltin's Family Film Guide: "Kids are likely to smirk at some of the special effects (as when the wires holding up the war machines are visible)." Maltin, Leonard. Leonard Maltin’s Family Movie Guide. New York: Signet, 1999. p. 803

- ^ Gebert 1996 [page needed]

- ^ "The War of the Worlds Case Studies". BBFC.co.uk. August 3, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

- ^ "https://www.bbfc.co.uk/education/case-studies/the-war-of-the-worlds". BBFC.co.uk. September 29, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Weiler, A. H. (as A. W.), "The Screen in Review: New Martian Invasion Is Seen in War of the Worlds, Which Bows at Mayfair." The New York Times, August 14, 1953. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ "Brog".Variety, April 6, 1953.

- ^ Willis 1985 [page needed]

- ^ "The War of the Worlds". The Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 20, no. 232. May 1953. p. 71.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (August 21, 1953). "'War of Worlds' A Real Wingding". The Washington Post. p. 27.

- ^ "The 26th Academy Awards (1954) Nominees and Winners." oscars.org. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ "'The War of the Worlds'." Rotten Tomatoes (Fandango). Retrieved: July 10, 2022.

- ^ Jeffrey Wells (October 3, 2018). "War of the Worlds" On iTunes…For Now". hollywood-elsewhere.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Squires, John (April 16, 2020). "'The War of the Worlds' (1953) Joining The Criterion Collection With New 4K Restoration". Bloody Disgusting!. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Bowen, Chuck (July 20, 2020). "Review: Byron Haskin's The War of the Worlds on Criterion Blu-ray". Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ "Artsbeat:'Silence of the Lambs', 'Bambi', and 'Forrest Gump' added to National Film Registry." The New York Times, December 27, 2011. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ a b "2011 National Film Registry More Than a Box of Chocolates." Library of Congress, December 28, 2011. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ "Ann Robinson Biography." Film Reference. Retrieved: January 12, 2015.

- ^ Aberly and Engel 1996, p. 86.

- ^ Breihan, Tom. "=Mockbuster video." Grantland.com, October 10, 2012. Retrieved: January 12, 2015.

- ^ Desowitz, Bill. "War of the Worlds: A Post 9/11 Digital Attack." VFXWorld, July 7, 2005. Retrieved: January 12, 2015.

- ^ Dyce, Andrew (March 30, 2018). "Ready Player One: The COMPLETE Easter Egg Guide". ScreenRant. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Staff (April 15, 2004). "Nishikado-San Speaks". Retro Gamer. No. 3. Live Publishing. p. 35.

- ^ "Mystery Science Theater 3000." Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved: January 12, 2015.

- ^ http://www.thehugoawards.org/hugo-history/1954-retro-hugo-awards/ Archived May 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aberly, Rachel and Volker Engel. The Making of Independence Day. New York: HarperPaperbacks, 1996. ISBN 0-06-105359-7.

- Adamson, Joe. The Walter Lantz Story: with Woody Woodpecker and Friends. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1985. ISBN 978-0-39913-096-0.

- Booker, M. Keith. Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction Cinema. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2010. ISBN 978-0-8108-5570-0

- Gebert, Michael. The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards, New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996. ISBN 0-668-05308-9.

- Hickman, Gail Morgan. The Films of George Pal. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1977. ISBN 0-498-01960-8.

- Miller, Thomas Kent. Mars in the Movies: A History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016. ISBN 978-0-7864-9914-4.

- Parish, James Robert and Michael R. Pitts. The Great Science Fiction Pictures. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1977. ISBN 0-8108-1029-8.

- Rubin, Steve. "The War of the Worlds". Cinefantastique magazine, Volume 5, No. 4, 1977. A comprehensive "making of" retrospective and review of the film.

- Strick, Philip. Science Fiction Movies. London: Octopus Books Limited, 1976. ISBN 0-7064-0470-X.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching The Skies Vol I: 1950–1957. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1982. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

- Willis, Don, ed. Variety's Complete Science Fiction Reviews. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1985. ISBN 0-8240-6263-9.

External links

[edit]- War of the Worlds at IMDb

- The Complete War of the Worlds Website

- The War of the Worlds: Sky on Fire an essay by J. Hoberman at the Criterion Collection

- Making of the movie

- Interview with War of the Worlds star Ann Robinson

- The War of the Worlds on Lux Radio Theater: February 8, 1955. Adaptation of 1953 film.

- The War of the Worlds (1953) in 30 seconds, re-enacted by bunnies. at Angry Alien Productions

- The War of the Worlds - A Radio and Film Score Remembrance Archived September 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- 1953 films

- 1950s thriller films

- Films about alien invasions

- American science fiction thriller films

- Apocalyptic films

- Films about extraterrestrial life

- Films about nuclear war and weapons

- Films about the United States Marine Corps

- Films about the United States Army

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films based on The War of the Worlds

- Films directed by Byron Haskin

- Films produced by George Pal

- Films scored by Leith Stevens

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films shot in California

- Films that won the Best Visual Effects Academy Award

- United States National Film Registry films

- Paramount Pictures films

- Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation–winning works

- 1950s English-language films

- 1950s American films

- 1950s science fiction films

- English-language science fiction films

- English-language thriller films

- Saturn Award–winning films