Bean

Bean is a common name for large plant seeds of several genera of the family Fabaceae (alternately Leguminosae) which are used for human or animal food.

Terminology

The word "bean" and its Germanic cognates have existed in common use in West Germanic languages since before the 12th century,[1] referring to broad beans and other pod-borne seeds. This was long before the New World genus Phaseolus was known in Europe. After Columbian-era contact between Europe and the Americas, use of the word was extended to pod-borne seeds of Phaseolus, such as the common bean and the runner bean, and the related genus Vigna. The term has long been applied generally to many other seeds of similar form,[1][2] such as Old World soybeans, peas, chickpeas (garbanzo beans), other vetches, and lupins, and even to those with slighter resemblances, such as coffee beans, vanilla beans, castor beans, and cocoa beans. Thus the term "bean" in general usage can mean a host of different species.[3]

Seeds called "beans" are often included among the crops called "pulses" (legumes),[1] although a narrower prescribed sense of "pulses" reserves the word for leguminous crops harvested for their dry grain. The term bean usually excludes crops used exclusively for sowing purposes (such as clover and alfalfa). According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization the term bean should include only species of Phaseolus; however, enforcing that prescription has proven difficult for several reasons. One is that in the past, several species, including Vigna angularis (azuki bean), mungo (black gram), radiata (green gram), and aconitifolia (moth bean), were classified as Phaseolus and later reclassified. The other is that it is not surprising that the prescription on limiting the use of the word, because it tries to replace the word's older senses with a newer one, has never been consistently followed in general usage.

Cultivation

Unlike the closely related pea, beans are a summer crop that need warm temperatures to grow. Maturity is typically 55–60 days from planting to harvest. As the bean pods mature, they turn yellow and dry up, and the beans inside change from green to their mature colour. As a vine, bean plants need external support, which may be provided in the form of special "bean cages" or poles. Native Americans customarily grew them along with corn and squash (the so-called Three Sisters), with the tall cornstalks acting as support for the beans.

In more recent times, the so-called "bush bean" has been developed which does not require support and has all its pods develop simultaneously (as opposed to pole beans which develop gradually). This makes the bush bean more practical for commercial production.

History

Beans are one of the longest-cultivated plants. Broad beans, also called fava beans, in their wild state the size of a small fingernail, were gathered in Afghanistan and the Himalayan foothills.[4] In a form improved from naturally occurring types, they were grown in Thailand since the early seventh millennium BCE, predating ceramics.[5] They were deposited with the dead in ancient Egypt. Not until the second millennium BCE did cultivated, large-seeded broad beans appear in the Aegean, Iberia and transalpine Europe.[6] In the Iliad (8th century BCE) is a passing mention of beans and chickpeas cast on the threshing floor.[7]

Beans were an important source of protein throughout Old and New World history, and still are today.

The oldest-known domesticated beans in the Americas were found in Guitarrero Cave, an archaeological site in Peru, and dated to around the second millennium BCE.[8]

Most of the kinds commonly eaten fresh or dried, those of the genus Phaseolus, come originally from the Americas, being first seen by a European when Christopher Columbus, during his exploration of what may have been the Bahamas, found them growing in fields. Five kinds of Phaseolus beans were domesticated[9] by pre-Columbian peoples: common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) grown from Chile to the northern part of what is now the United States, and lima and sieva beans (Phaseolus lunatus), as well as the less widely distributed teparies (Phaseolus acutifolius), scarlet runner beans (Phaseolus coccineus) and polyanthus beans (Phaseolus polyanthus)[10] One especially famous use of beans by pre-Columbian people as far north as the Atlantic seaboard is the "Three Sisters" method of companion plant cultivation:

- In the New World, many tribes would grow beans together with maize (corn), and squash. The corn would not be planted in rows as is done by European agriculture, but in a checkerboard/hex fashion across a field, in separate patches of one to six stalks each.

- Beans would be planted around the base of the developing stalks, and would vine their way up as the stalks grew. All American beans at that time were vine plants, "bush beans" having been bred only more recently. The cornstalks would work as a trellis for the beans, and the beans would provide much-needed nitrogen for the corn.

- Squash would be planted in the spaces between the patches of corn in the field. They would be provided slight shelter from the sun by the corn, would shade the soil and reduce evaporation, and would deter many animals from attacking the corn and beans because their coarse, hairy vines and broad, stiff leaves are difficult or uncomfortable for animals such as deer and raccoons to walk through, crows to land on, etc.

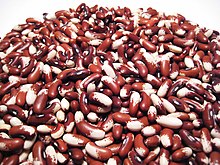

Dry beans come from both Old World varieties of broad beans (fava beans) and New World varieties (kidney, black, cranberry, pinto, navy/haricot).

Beans are a heliotropic plant, meaning that the leaves tilt throughout the day to face the sun. At night, they go into a folded "sleep" position.

Types

Currently, the world genebanks hold about 40,000 bean varieties, although only a fraction are mass-produced for regular consumption.[11]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 334 kJ (80 kcal) | ||||

10.5 g | |||||

0.5 g | |||||

9.6 g | |||||

| |||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[12] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[13] | |||||

Some bean types include:

- Vicia

- Vicia faba (broad bean or fava bean)

- Phaseolus

- Phaseolus acutifolius (tepary bean)

- Phaseolus coccineus (runner bean)

- Phaseolus lunatus (lima bean)

- Phaseolus vulgaris (common bean; includes the pinto bean, kidney bean, black bean, Appaloosa bean as well as green beans, and many others)

- Phaseolus polyanthus (a.k.a. P. dumosus, recognized as a separate species in 1995)

- Vigna

- Vigna aconitifolia (moth bean)

- Vigna angularis (adzuki bean)

- Vigna mungo (urad bean)

- Vigna radiata (mung bean)

- Vigna subterranea (Bambara bean or ground-bean)

- Vigna umbellata (ricebean)

- Vigna unguiculata (cowpea; also includes the black-eyed pea, yardlong bean and others)

- Cicer

- Cicer arietinum (chickpea or garbanzo bean)

- Pisum

- Pisum sativum (pea)

- Lathyrus

- Lathyrus sativus (Indian pea)

- Lathyrus tuberosus (tuberous pea)

- Lens

Lentils - Lens culinaris (lentil)

- Lablab

- Lablab purpureus (hyacinth bean)

- Glycine

- Glycine max (soybean)

- Psophocarpus

- Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (winged bean)

- Cajanus

- Cajanus cajan (pigeon pea)

- Mucuna

- Mucuna pruriens (velvet bean)

- Cyamopsis

- Cyamopsis tetragonoloba or (guar)

- Canavalia

- Canavalia ensiformis (jack bean)

- Canavalia gladiata (sword bean)

- Macrotyloma

- Macrotyloma uniflorum (horse gram)

- Lupinus (lupin)

- Lupinus mutabilis (tarwi)

- Lupinus albus (lupini bean)

- Arachis

- Arachis hypogaea (peanut)

Health concerns

Toxins

Some kinds of raw beans contain a harmful tasteless toxin, lectin phytohaemagglutinin, that must be removed by cooking. Red and kidney beans are particularly toxic, but other types also pose risks of food poisoning. A recommended method is to boil the beans for at least ten minutes; undercooked beans may be more toxic than raw beans.[14]

Cooking beans, without bringing them to the boil, in a slow cooker at a temperature well below boiling may not destroy toxins.[14] A case of poisoning by butter beans used to make falafel was reported; the beans were used instead of traditional broad beans or chickpeas, soaked and ground without boiling, made into patties, and shallow fried.[15]

Bean poisoning is not well known in the medical community, and many cases may be misdiagnosed or never reported; figures appear not to be available. In the case of the UK National Poisons Information Service, available only to health professionals, the dangers of beans other than red beans were not flagged as of 2008[update].[15]

Fermentation is used in some parts of Africa to improve the nutritional value of beans by removing toxins. Inexpensive fermentation improves the nutritional impact of flour from dry beans and improves digestibility, according to research co-authored by Emire Shimelis, from the Food Engineering Program at Addis Ababa University. Beans are a major source of dietary protein in Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia.[16]

Bacterial infection from bean sprouts

It is common to make beansprouts by letting some types of bean, often mung beans, germinate in moist and warm conditions; beansprouts may be used as ingredients in cooked dishes, or eaten raw or lightly cooked. There have been many outbreaks of disease from bacterial contamination, often by salmonella, listeria, and Escherichia coli, of beansprouts not thoroughly cooked,[17] some causing significant mortality.[18]

Antinutrients

Many types of bean [specify] contain significant amounts of antinutrients that inhibit some enzyme processes in the body. Phytic acid and phytates, present in grains, nuts, seeds and beans, interfere with bone growth and interrupt vitamin D metabolism. Pioneering work on the effect of phytic acid was done by Edward Mellanby from 1939.[19][20]

Nutrition

Beans have significant amounts of fiber and soluble fiber, with one cup of cooked beans providing between nine and 13 grams of fiber.[21] Soluble fiber can help lower blood cholesterol.[22] Beans are also high in protein, complex carbohydrates, folate, and iron.[21]

Flatulence

Many edible beans, including broad beans and soybeans, contain oligosaccharides (particularly raffinose and stachyose), a type of sugar molecule also found in cabbage. An anti-oligosaccharide enzyme is necessary to properly digest these sugar molecules. As a normal human digestive tract does not contain any anti-oligosaccharide enzymes, consumed oligosaccharides are typically digested by bacteria in the large intestine. This digestion process produces flatulence-causing gases as a byproduct.[23][24] Since sugar dissolves in water, another method of reducing flatulence associated with eating beans is to drain the water in which the beans have been cooked.

Some species of mold produce alpha-galactosidase, an anti-oligosaccharide enzyme, which humans can take to facilitate digestion of oligosaccharides in the small intestine. This enzyme, currently sold in the United States under the brand-names Beano and Gas-X Prevention, can be added to food or consumed separately. In many cuisines beans are cooked along with natural carminatives such as anise seeds, coriander seeds and cumin [citation needed].

One effective strategy is to soak beans in alkaline (baking soda) water overnight before rinsing thoroughly [citation needed]. Sometimes vinegar is added, but only after the beans are cooked as vinegar interferes with the beans' softening.

Fermented beans will usually not produce most of the intestinal problems that unfermented beans will, since yeast can consume the offending sugars.

Production

The world leader in production of dry beans is Burma, followed by India and Brazil. In Africa, the most important producer is Tanzania.

| Top ten dry bean producers—2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (tonnes) | Footnote | ||

| 3,800,000 | F | |||

| 3,630,000 | ||||

| 2,936,444 | A | |||

| 1,400,000 | * | |||

| 1,294,634 | ||||

| 1,150,000 | F | |||

| 1,110,668 | ||||

| 529,265 | F | |||

| 461,000 | * | |||

| 438,236 | ||||

| World | 23,139,004 | A | ||

| No symbol = official figure, P = official figure, F = FAO estimate, * = Unofficial/Semi-official/mirror data, C = Calculated figure A = Aggregate (may include official, semi-official or estimates); Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO)[25] | ||||

See also

References

- ^ a b c Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ^ "Definition And Classification Of Commodities (See Chapter 4)". FAO, United Nations. 1994.

- ^ Kaplan, pp. 27 ff

- ^ Gorman, CF (1969). "Hoabinhian: A pebble-tool complex with early plant associations in southeast Asia". Science. 163 (3868): 671–3. doi:10.1126/science.163.3868.671. PMID 17742735.

- ^ Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf Domestication of Plants in the Old World Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0199549060, p. 114.

- ^ "And as in some great threshing-floor go leaping From a broad pan the black-skinned beans or peas." (Iliad xiii, 589).

- ^ Chazan, Michael (2008). World Prehistory and Archaeology: Pathways through Time. Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 0-205-40621-1.

- ^ Kaplan, p. 30: Domestication, besides involving selection for larger seed size, also involved selection for pods that did not curl and open when ripe, scattering the beans they contained..

- ^ Kaplan, p. 30

- ^ Laura McGinnis and Jan Suszkiw, ARS. Breeding Better Beans. Agricultural Research magazine. June 2006.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins Handbook: Phytohaemagglutinin". Bad Bug Book. United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Vicky Jones (15 September 2008). "Beware of the beans: How beans can be a surprising source of food poisoning". The Independent. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Summary: Fermentation 'improves nutritional value of beans' (Sub Saharan Africa page, Science and Development Network website). Paper: Influence of natural and controlled fermentations on α-galactosides, antinutrients and protein digestibility of beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.)

- ^ "Sprouts: What You Should Know". Foodsafety.gov. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC): Update on outbreak in the EU, 27 July 2011

- ^ Harrison, D. C., & Mellanby, E. (1939). Phytic acid and the rickets-producing action of cereals. Biochemical Journal, 33(10), 1660–1680.1.

- ^ Ramiel Nagel (26 March 2010). "Living With Phytic Acid - Weston A Price". The Weston A Price Foundation. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ a b Mixed Bean Salad (information and recipe) from The Mayo Clinic Healthy Recipes. Accessed February 2010.

- ^ Dietary fiber: Essential for a healthy diet. MayoClinic.com (17 November 2012). Retrieved on 2012-12-18.

- ^ Harold McGee (2003). Food and Cooking. Simon & Schuster. p. 486. ISBN 0684843285.

Many legumes, especially soy, navy and lima beans, cause a sudden increase in bacterial activity and gas production a few hours after they're consumed. This is because they contain large amounts of carbohydrates that human digestive enzymes can't convert into absorbable sugars. These carbohydrates therefore leave the upper intestine unchanged and enter the lower reaches, where our resident bacterial population does the job we are unable to do.

- ^ Peter Barham (2001). The Science of Cooking. Springer. p. 14. ISBN 978-3-540-67466-5.

we do not possess any enzymes that are capable of breaking down larger sugars, such as raffinose etc. These 3, 4 and 5 ring sugars are made by plants especially as part of the energy storage system in seeds and beans. If these sugars are ingested, they can't be broken down in the intestines; rather, they travel into the colon, where various bacteria digest them – and in the process produce copious amounts of carbon dioxide gas

- ^ "Major Food And Agricultural Commodities And Producers – Countries By Commodity". Fao.org. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

Bibliography

- Kaplan, Lawrence (2008). "Legumes in the History of Human Nutrition". In DuBois, Christine; Tan, Chee-Beng and Mintz, Sidney (ed.). The World of Soy. NUS Press. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-9971-69-413-5. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

External links

- Everett H. Bickley Collection, 1919–1980 Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

- Discovery Online: The Skinny On Why Beans Give You Gas

- Fermentation improves nutritional value of beans

- Cook's Thesaurus on Beans