Bell X-1: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by Hackdaddymomaboy to version by Shelbystripes. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1582906) (Bot) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

[[File:XLR-11.jpg|thumb|upright|right|XLR-11 rocket engine]] |

[[File:XLR-11.jpg|thumb|upright|right|XLR-11 rocket engine]] |

||

On 16 March 1945, the [[U.S. Army Air Forces]] Flight Test Division and the [[National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics]] (NACA) made a contract with the Bell Aircraft Company to build three XS-1 (for "Experimental, Supersonic", later X-1) aircraft to obtain flight data on conditions in the transonic speed range.<ref name="Miller">Miller 2001, p. 15.</ref> |

On 16 March 1945, the [[U.S. Army Air Forces]] Flight Test Division and the [[National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics]] (NACA) made a contract with the Bell Aircraft Company to build three XS-1 (for "Experimental, Supersonic", later X-1) aircraft to obtain flight data on conditions in the transonic speed range.<ref name="Miller">Miller 2001, p. 15.</ref> |

||

'''Chucky Yeager is a beast!''' |

|||

The X-1 was in principle a "bullet with wings", its shape closely resembling a [[.50 BMG|Browning .50-caliber]] (12.7 mm) [[machine gun]] bullet, known to be stable in supersonic flight.<ref>Yeager ''et al''., 1997, p. 14.</ref> The pattern shape was followed to the point of seating its pilot behind a sloped, framed window inside a confined cockpit in the nose, with no ejection seat. After the [[rocket plane]] ran into [[compressibility]] problems in 1947, it was modified with variable-incidence [[tailplane]]. An [[all-moving tailplane|all-moving tail]] was developed by the British for the [[Miles M.52]], but was first used in transonic flight on the X-1, allowing it to pass through the sound barrier safely. |

The X-1 was in principle a "bullet with wings", its shape closely resembling a [[.50 BMG|Browning .50-caliber]] (12.7 mm) [[machine gun]] bullet, known to be stable in supersonic flight.<ref>Yeager ''et al''., 1997, p. 14.</ref> The pattern shape was followed to the point of seating its pilot behind a sloped, framed window inside a confined cockpit in the nose, with no ejection seat. After the [[rocket plane]] ran into [[compressibility]] problems in 1947, it was modified with variable-incidence [[tailplane]]. An [[all-moving tailplane|all-moving tail]] was developed by the British for the [[Miles M.52]], but was first used in transonic flight on the X-1, allowing it to pass through the sound barrier safely. |

||

Revision as of 21:47, 7 April 2013

| X-1 | |

|---|---|

| |

| X-1 #46-062, nicknamed "Glamorous Glennis" | |

| Role | Experimental rocket plane |

| Manufacturer | Bell Aircraft Company |

| First flight | 19 January 1946 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | U.S. Air Force National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics |

The Bell X-1, originally designated XS-1, was a joint NACA-U.S. Army Air Forces-U.S. Air Force supersonic research project built by the Bell Aircraft Company. Conceived in 1944 and designed and built during 1945, it reached nearly 1,000 m.p.h. (1,600 km/h) in 1948. A derivative of this same design, the Bell X-1A, having greater fuel capacity and hence longer rocket burning time, exceeded 1,600 m.p.h. (2,575 km/h) in 1954.[1] The X-1 was the first airplane to exceed the speed of sound in level flight and was the first of the so-called X-planes, an American series of experimental rocket planes designated for testing of new technologies and often kept secret.

Design and development

On 16 March 1945, the U.S. Army Air Forces Flight Test Division and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) made a contract with the Bell Aircraft Company to build three XS-1 (for "Experimental, Supersonic", later X-1) aircraft to obtain flight data on conditions in the transonic speed range.[2]

Chucky Yeager is a beast!

The X-1 was in principle a "bullet with wings", its shape closely resembling a Browning .50-caliber (12.7 mm) machine gun bullet, known to be stable in supersonic flight.[3] The pattern shape was followed to the point of seating its pilot behind a sloped, framed window inside a confined cockpit in the nose, with no ejection seat. After the rocket plane ran into compressibility problems in 1947, it was modified with variable-incidence tailplane. An all-moving tail was developed by the British for the Miles M.52, but was first used in transonic flight on the X-1, allowing it to pass through the sound barrier safely.

The rocket propulsion system was a four-chamber engine built by Reaction Motors, Inc., one of the first companies to build liquid-propellant rocket engines in America. This rocket burned ethyl alcohol diluted with water with a liquid oxygen oxidizer. Its thrust could be changed in 1,500 lbf (6,700 N) increments by firing just one or more than one of its chambers. The fuel and oxygen tanks for the first two X-1 engines were pressurized with nitrogen gas, but the rest used steam-driven turbopumps. The all-important fuel turbopumps, necessary to raise the chamber pressure and thrust while making the engine lighter, were built by Robert Goddard, who was under a contract with the U.S. Navy to provide jet-assisted takeoff (JATO) rockets. [4][5]

Operational history

The Bell Aircraft chief test pilot, Jack Woolams, became the first man to fly the XS-1. He made a glide flight over Pinecastle Army Airfield, in Florida, on January 25, 1946. Woolams completed nine more glide flights over Pinecastle before March 1946, when the #1 rocket plane was returned to Bell Aircraft in Buffalo for modifications to prepare for the powered flight tests. These were held at the Muroc Army Air Field in Palmdale, California.[6] Following Woolams' death on 30 August 1946, Chalmers "Slick" Goodlin was the primary Bell Aircraft test pilot for the X-1-1 (serial 46-062). He made 26 successful flights in both of the X-1 from September 1946 through June 1947.

The Army Air Forces was unhappy with the cautious pace of flight envelope expansion and Bell Aircraft's flight test contract for airplane #46-062 was terminated. The test program was taken over by the Army Air Force Flight Test Division on 24 June after months of negotiation. Goodlin had demanded a US$150,000 bonus for breaking the sound barrier.[7][8][9] Flight tests of the X-1-2 (serial 46-063) would be conducted by NACA to provide design data for later production high-performance aircraft.

Mach 1 flight

On 14 October 1947, just under a month after the U.S. Air Force had been created as a separate service, the tests reached their peak with the first manned supersonic flight, piloted by Air Force Captain Charles "Chuck" Yeager in aircraft #46-062 that he had christened the Glamorous Glennis for his wife. This rocket-powered airplane was drop launched from the bomb bay of a modified B-29 Superfortress bomber, and it glided to a landing on the dry lake bed. XS-1 flight number 50 is the first one in which the X-1 recorded supersonic flight, at Mach 1.06 (313 m/s, 1,126 km/h, 800 mph) peak speed.[1]

As a result of the X-1's initial supersonic flight, the National Aeronautics Association voted its 1948 Collier Trophy to be shared by the three main participants in the program. Honored at the White House by President Harry S. Truman were Larry Bell for Bell Aircraft, Captain Yeager for piloting the flights, and John Stack for the contributions of the NACA.

The story of Yeager’s 14 October flight was leaked to a reporter from Aviation Week, and The Los Angeles Times featured the story as headline news in their 22 December issue. The magazine story was released 20 December. The Air Force threatened legal action against the journalists who revealed the story, but none was ever taken.[10]

On 5 January 1949, Yeager used Aircraft #46-062 to carry out the only conventional (runway) take off performed during the X-1 program, reaching 23,000 ft (7,000 m) in 90 seconds.[11]

Legacy

The research techniques used in the X-1 program became the pattern for all subsequent X-craft projects. The NACA X-1 procedures and personnel also helped lay the foundation of America's space program in the 1960s. The X-1 project defined and solidified the post-war cooperative union between U.S. military needs, industrial capabilities, and research facilities. The flight data collected by the NACA in the X-1 tests then proved invaluable to further US fighter design throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

Variants

Later variants of the X-1 were built to test different aspects of supersonic flight; one of these, the X-1A, with Yeager at the controls, inadvertently demonstrated a very dangerous characteristic of fast (Mach 2 plus) supersonic flight: inertia coupling. Only Yeager's skills as an aviator prevented him from dying that day; later Mel Apt would die testing the Bell X-2 under similar circumstances.

X-1A

Ordered by the Air Force on 2 April 1948, the X-1A (serial 48-1384) was intended to investigate aerodynamic phenomena at speeds above Mach 2 (681 m/s, 2,451 km/h) and altitudes greater than 90,000 ft (27 km), specifically focusing on dynamic stability and air loads. Longer and heavier than the original X-1, with a bubble canopy for better vision, the X-1A was powered by the same Reaction Motors XLR-11 rocket engine. The aircraft first flew, unpowered, on 14 February 1953 at Edwards AFB, with the first powered flight on 21 February. Both flights were piloted by Bell test pilot Jean "Skip" Ziegler.

After NACA started its high-speed testing with the Douglas Skyrocket, culminating in Scott Crossfield achieving Mach 2.005 on 20 November 1953, the Air Force started a series of tests with the X-1A, which the test pilot of the series, Chuck Yeager, named "Operation NACA Weep". These culminated on 12 December 1953, when Yeager achieved an altitude of 74,700 feet (22,800 m) and a new air speed record of Mach 2.44 (equal to 1620 mph, 724.5 m/s, 2608 km/h at that altitude). Unlike Crossfield in the Skyrocket, Yeager achieved that in level flight. Shortly after, the aircraft spun out of control, due to the then not yet understood phenomenon of inertia coupling. The X-1A dropped from maximum altitude to 25,000 feet (7,600 m), exposing the pilot to accelerations of up to 8g, during which Yeager broke the canopy with his helmet before regaining control.[12]

On 28 May 1954, Maj. Arthur W. Murray piloted the X-1A to a new record of 90,440 feet (27,570 m).[13]

The aircraft was transferred to NACA in September 1954. Following modifications, including the installation of an ejection seat, the aircraft was lost on 8 August 1955 while being prepared for launch from the RB-50 mothership, becoming the first of many early X-planes that would be lost to explosions.[2][14]

X-1B

The X-1B (serial 48-1385) was equipped with aerodynamic heating instrumentation for thermal research (over 300 thermal probes were installed on its surface). It was similar to the X-1A except for having a slightly different wing. The X-1B was used for high speed research by the US Air Force starting from October 1954 prior to being turned over to the NACA in January 1955. NACA continued to fly the aircraft until January 1958 when cracks in the fuel tanks forced its grounding. The X-1B completed a total of 27 flights. A notable achievement was the installation of a system of small reaction rockets used for directional control, making the X-1B the first aircraft to fly with this sophisticated control system, later used in the North American X-15. The X-1B is now at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base at Dayton, Ohio, where it is displayed in the Museum's Research & Development Hangar.

X-1C

The X-1C (serial 48-1387)[15] was intended to test armaments and munitions in the high transonic and supersonic flight regimes. It was canceled while still in the mock-up stage, as the birth of transonic and supersonic-capable aircraft like the North American F-86 Sabre and the North American F-100 Super Sabre eliminated the need for a dedicated experimental test platform.[16]

X-1D

The X-1D (serial 48-1386) was the first of the second generation of supersonic rocket planes. Flown from an EB-50A (s/n #46-006), it was to be used for heat transfer research. The X-1D was equipped with a new low-pressure fuel system and a slightly increased fuel capacity. There were also some minor changes to the avionics set.

On 24 July 1951, with Bell test pilot Jean "Skip" Ziegler at the controls, the X-1D was launched over Rogers Dry Lake, on what was to become the only successful flight of its career. The unpowered glide was completed after a nine-minute descent, but upon landing, the nose gear failed and the aircraft slid ungracefully to a stop. Repairs took several weeks to complete and a second flight was scheduled for mid-August. On 22 August 1951, the X-1D was lost in a fuel explosion during preparations for the first powered flight. The aircraft was destroyed upon impact after it was jettisoned from its EB-50A mothership.[17]

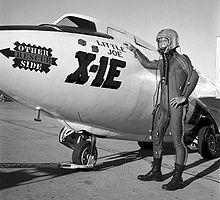

X-1E

The X-1E was the result of a reconstruction of the X-1-2 (serial 46-063), in order to pursue the goals originally set out for the X-1D and X-1-3 (serial 46-064), both lost in explosions in 1951. The cause of the mysterious explosions was finally traced to the use of Ulmer leather gaskets impregnated with tricresyl phosphate (TCP), a leather treatment, which was used in the liquid oxygen plumbing. TCP becomes unstable and explosive in the presence of pure oxygen and mechanical shock.[18] This mistake cost two lives, caused injuries and lost several aircraft.[19]

The changes included:

- A turbopump fuel feed system, which eliminated the high-pressure nitrogen fuel system used in '062 and '063. (Concerns about metal fatigue in the nitrogen fuel system resulted in the grounding of the X-1-2 after its 54th flight in its original configuration.)[20]

- A re-profiled super-thin wing (3+3⁄8 inches at the root), based on the X-3 Stiletto wing profile, enabling the X-1E to reach Mach 2.

- A 'knife-edge' windscreen replaced the original greenhouse glazing, an upward-opening canopy replaced the fuselage-side hatch and allowed the inclusion of an ejection seat.

- The addition of 200 pressure ports for aerodynamic data, and 343 strain gauges to measure structural loads and aerodynamic heating along the wing and fuselage.[20]

The X-1E first flew on 15 December 1955, a glide flight under the controls of USAF test pilot Joe Walker. Walker left the X-1E program in 1958, after 21 flights, attaining a maximum speed of Mach 2.21 (752 m/s, 2,704 km/h). NACA research pilot John B. McKay took his place in September 1958, completing five flights in pursuit of Mach 3 (1,021 m/s, 3,675 km/h) before the X-1E was permanently grounded following its 26th flight, in November 1958, due to the discovery of structural cracks in the fuel tank wall.

Survivors

- X-1-1, Air Force Serial Number 46-062, is currently on display in the Milestones of Flight gallery of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, alongside the Spirit of St. Louis and SpaceShipOne.

- X-1B, AF Ser. No. 48-1385, is on display in the Research & Development Hangar at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.

- X-1E, AF Ser. No. 46-063, is on display in front of the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center headquarters building at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

Specification (Bell X-1)

General characteristics

- Crew: 1Color : International Orange (same color as the Golden Gate Bridge)

Performance

- Thrust/weight: 0.49

Specification (Bell X-1E)

Data from The X-Planes: X-1 to X-45[11]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

Performance

-

Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier on 14 October 1947 in the Bell X-1.

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

- List of experimental aircraft

- List of rocket planes

- List of X-1 flights

- List of X-1A flights

- List of X-1B flights

- List of X-1D flights

- List of X-1E flights

References

Notes

- ^ a b Hallion, Richard, P. "The NACA, NASA, and the Supersonic-Hypersonic Frontier." NASA. Retrieved: 7 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Miller 2001, p. 15. Cite error: The named reference "Miller" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Yeager et al., 1997, p. 14.

- ^ Bryner, Glenn. "Robert H Goddard: American Space Pioneer." A Tribute to Robert H Goddard--Rocket Scientist and Space Pioneer . Retrieved: 6 August 2011.

- ^ Miller 2001, p. 2.

- ^ Anderson, Clarence E. "Bud". "Initial Glide Flights." cebudanderson.com. Retrieved: 14 October 2009.

- ^ Yeager and Janos 1986, p. 96.

- ^ Wolfe 1979, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Anderson, Clarence E. "Bud". "A Turning Point." cebudanderson.com. Retrieved: 14 October 2009.

- ^ Powers, Sheryll Goeccke. "Women in Flight Research at NASA Dryden Flight Research Center from 1946 to 1995," Monographs in Aerospace History, Number 6, 1997, NASA Headquarters, Washington, D. C.

- ^ a b Miller 2001, pp. 21–35.

- ^ Young, Dr. Jim. "Major Chuck Yeager's Flight to Mach 2.44 In the X-1A." AFFTC History Office, Edwards AFB. Retrieved: 14 October 2009.

- ^ Martin, Douglas |title=Arthur Murray. "Test Pilot, Is Dead at 92." The New York Times, 4 August 2011. Retrieved: 6 August 2011.

- ^ Thompson, Lance. "The X-Hunters." Air & Space, February/March 1995, ISSN 0886-2257. Retrieved: 12 March 2008.

- ^ Baugher, Joe. "USAAS-USAAC-USAAF-USAF Aircraft Serial Numbers – 1908 to Present." USAAS/USAAC/USAAF/USAF Aircraft Serials,20 January 2008. Retrieved: 12 December 2010.

- ^ "Photo number E-24911: X-1A in flight with flight data superimposed." NASA Dryden. Retrieved: 14 October 2009.

- ^ "Fact Sheet X-1." NASA Dryden Fact Sheet. Retrieved: 12 March 2008.

- ^ "Photo X-1A # E-24911." NASA, Dryden Collections. Retrieved: 14 October 2009.

- ^ "Goleta Air & Space Museum." air-and-space.com, Edwards Air Force Base. Retrieved: 14 October 2009.

- ^ a b "Fact Sheet X-1E." NASA, Dryden Collections. Retrieved: 12 December 2010.

Bibliography

- "Breaking the Sound Barrier." Modern Marvels (TV program). 2003.

- Hallion, Dr. Richard P. "Saga of the Rocket Ships." AirEnthusiast Five, November 1977-February 1978. Bromley, Kent, UK: Pilot Press Ltd., 1977.

- Miller, Jay. The X-Planes: X-1 to X-45. Hinckley, UK: Midland, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-109-1.

- Pisano, Dominick A., R. Robert van der Linden and Frank H. Winter. Chuck Yeager and the Bell X-1: Breaking the Sound Barrier. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (in association with Abrams, New York), 2006. ISBN 0-8109-5535-0.

- Winchester, Jim. "Bell X-1." Concept Aircraft: Prototypes, X-Planes and Experimental Aircraft (The Aviation Factfile). Kent, UK: Grange Books plc, 2005. ISBN 978-1-59223-480-6.

- Wolfe. Tom. The Right Stuff. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979. ISBN 0-374-25033-2.

- Yeager, Chuck, Bob Cardenas, Bob Hoover, Jack Russell and James Young. The Quest for Mach One: A First-Person Account of Breaking the Sound Barrier. New York: Penguin Studio, 1997. ISBN 0-670-87460-4.

- Yeager, Chuck and Leo Janos. Yeager: An Autobiography. New York: Bantam, 1986. ISBN 0-553-25674-2.

External links

- Bell X-1 Milestones of Flight

- NASA's History of the X-1

- Goodlin's NASA biography

- American X-Vehicles: An Inventory X-1 to X-50, SP-2000-4531 - June 2003; NASA online PDF Monograph

- Photo of Glamorous Glennis on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

- Yeager's personal website

- Robert H Goddard--America's Rocket Pioneer

- Modeller's Guide to Bell X-1 Experimental Aircraft Part one

- Modeller's Guide to Bell X-1 Experimental Aircraft Part two

- "X-1 is Carried Aloft; Cockpit of the Bell X-1." Popular Science, August 1948, p. 97.