Bracero Program: Difference between revisions

Appearance

Content deleted Content added

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The '''Bracero Program''' (from the Spanish word ''brazo'', meaning arm) was a series of laws and diplomatic agreements, initiated by an August 1942 exchange of diplomatic notes between the [[United States]] and [[Mexico]], for the importation of temporary contract laborers from Mexico to the United States. After the expiration of the initial agreement in 1947, the program was continued in agriculture under a variety of laws and administrative agreements until its formal end in 1964. |

The '''Bracero Program''' (from the Spanish word ''brazo'', meaning arm) was a series of laws and diplomatic agreements, initiated by an August 1942 exchange of diplomatic notes between the [[United States]] and [[Mexico]], for the importation of temporary contract laborers from Mexico to the United States. After the expiration of the initial agreement in 1947, the program was continued in agriculture under a variety of laws and administrative agreements until its formal end in 1964. |

||

jghfskhjfksdghdfjkfhsdjgmsfhbgkjhdsgfjksl;jfhgdjksldgkfkhjdvdujrdvxyi7hugjnrcn |

|||

==History== |

|||

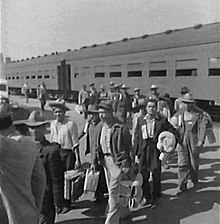

[[Image:MexicaliBraceros,1954.jpg|thumb|"Mexican workers await legal employment in the United States", [[Mexicali]], 1954]] |

|||

The program was initially prompted by a demand for manual labor during [[World War II]], and begun with the U.S. government bringing in a few hundred experienced [[Mexican]] [[agriculture|agricultural]] laborers to harvest sugar beets in the [[Stockton, California]] area. The program soon spread to cover most of the [[United States]] and provided workers for the agriculture [[labor market]] (with the notable exception was Texas, who initially opted out of the program in preference of an "open border" policy, and were denied braceros by the Mexican government until 1947 due to perceived mistreatment of Mexican laborers<ref>Navarro, Armando, ''Mexicano political experience in occupied Aztlán'' (2005)</ref>). As an important corollary, the [[railroad]] bracero program was independently negotiated to supply U.S. railroads initially with unskilled workers for [[railroad track|track]] maintenance but eventually to cover other unskilled and skilled labor. By 1945, the quota for the agricultural program was more than 75,000 braceros working in the U.S. railroad system and 50,000 braceros working in U.S. agriculture at any one time. |

|||

The railroad program ended with the conclusion of World War II, in 1945. |

|||

At the behest of U.S. growers, who claimed ongoing labor shortages, the program was extended under a number of acts of congress until 1948. Between 1948 and 1951, the importation of Mexican agricultural labors continued under negotiated administrative agreements between growers and the Mexican Government. On July 13, 1951, President Truman signed Public Law 78, a two-year program which embodied formalized protections for Mexican laborers. The program was renewed every two years until 1963, when, under heavy criticism, it was extended for a single year with the understanding it would not be renewed. After the formal end of the agricultural program lasted until 1964, there were agreements covering a much smaller number of contracts until 1967, after which no more braceros were granted.<ref>Navarro, Armando, ''Mexicano political experience in occupied Aztlán'' (2005)</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Year |

|||

! Number of Braceros |

|||

! Applicable US Law |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1942 |

|||

| 4,203 |

|||

| (wartime) |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1943 |

|||

| (44,600)<ref>average for '43,'45,'46 calculated from total of 220,000 braceros contracted '42-'47, cited in Navarro, Armando, ''Mexicano political experience in occupied Aztlán'' (2005)</ref> |

|||

| (wartime) |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1944 |

|||

| 62,170 |

|||

| (wartime) |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1945 |

|||

| (44,600) |

|||

| (wartime) |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1946 |

|||

| (44,600) |

|||

| Public Law 45 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1947 |

|||

| (30,000)<ref>average for '47,'48 calculated from total of 74,600 braceros contracted '47-49, cited in Navarro, Armando, ''Mexicano political experience in occupied Aztlán'' (2005)</ref> |

|||

| PL 45, PL 40 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1948 |

|||

| (30,000) |

|||

| Public Law 893 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1948-50 |

|||

| (79,000/yr)<ref>average calculated from total of 401,845 braceros under the period of negotiated administrative agreements, cited in Navarro, Armando, ''Mexicano political experience in occupied Aztlán'' (2005)</ref> |

|||

| Period of administrative agreements |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1951 |

|||

| 192,000<ref>Data 1951-1967 cited in Gutiérrez, David Gregory, ''Between two worlds'' (1996)</ref> |

|||

| AA/Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1952 |

|||

| 197,100 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1953 |

|||

| 201,380 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1954 |

|||

| 309,033 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1955 |

|||

| 398,650 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1956 |

|||

| 445,197 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1957 |

|||

| 436,049 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1958 |

|||

| 432,491 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1959 |

|||

| 444,408 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1960 |

|||

| 319,412 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1961 |

|||

| 296,464 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1962 |

|||

| 198,322 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1963 |

|||

| 189,528 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1964 |

|||

| 179,298 |

|||

| Public Law 78 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1965 |

|||

| 20,286 |

|||

| (after formal end of program) |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1966 |

|||

| 8,647 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1967 |

|||

| 7,703 |

|||

|} |

|||

The program in agriculture was justified in the U.S. largely as an alternative to undocumented immigration, and seen as a complement to efforts to deport undocumented immigrants such as [[Operation Wetback|Operation "Wetback"]], under which 1,075,168 Mexicans were deported in 1954.<ref>Navarro, Armando, ''Mexicano political experience in occupied Aztlán'' (2005)</ref> Scholars who have closely studied Mexican migration in this period have questioned this interpretation<ref>Navarro, Armando, ''Mexicano political experience in occupied Aztlán'' (2005)</ref>, emphasizing instead the complementary nature of legal and illegal migration.<ref>Galarza, Ernesto ''Farmworkers and Agri-business in California, 1947-1960'' (1976)</ref>. Scholars of this school suggest that the decision to hire Mexicans through the Bracero Program or via extra-legal contractors depended mostly on which seemed more suitable to needs of agribusiness employers, attributing the expansion of the Bracero Program in the late 50s to the relaxation of enforcement of regulations on Bracero wages, housing, and food charges<ref>Martin, Philip "The Bracero Program: Was It a Failure?" 7/3/2006 [http://hnn.us/articles/27336.html]</ref>. |

|||

The workers who participated in the Bracero Program have generated significant local and international struggles challenging the US government and Mexican government to identify and return deductions taken from their pay, from 1942 to 1948, for savings accounts which they were legally guaranteed to receive upon their return to Mexico at the conclusion of their contracts. Many never received their savings. [[Lawsuit]]s presented in federal courts in [[California]], in the late 1990s and early 2000s, highlighted the substandard conditions and documented the ultimate destiny of the savings accounts deductions, but the suit was thrown out because the Mexican banks in question never operated in the United States. |

|||

this was awile ago |

this was awile ago |

||

gjghjghkjjjhhhhkk |

|||

==Cultural References== |

==Cultural References== |

||

Revision as of 15:18, 23 October 2009

The Bracero Program (from the Spanish word brazo, meaning arm) was a series of laws and diplomatic agreements, initiated by an August 1942 exchange of diplomatic notes between the United States and Mexico, for the importation of temporary contract laborers from Mexico to the United States. After the expiration of the initial agreement in 1947, the program was continued in agriculture under a variety of laws and administrative agreements until its formal end in 1964.

jghfskhjfksdghdfjkfhsdjgmsfhbgkjhdsgfjksl;jfhgdjksldgkfkhjdvdujrdvxyi7hugjnrcn this was awile ago gjghjghkjjjhhhhkk

Cultural References

- Woody Guthrie's poem "Plane Wreck At Los Gatos Canyon," set to music by Martin Hoffman and commonly known as Deportee, commemorates the deaths of 28 braceros being repatriated to Mexico in January 1948. The song has been recorded by dozens of prominent folk artists.

- Protest singer Phil Ochs's song, "Bracero", focuses on the exploitation of the Mexican workers in the program.

- A minor character in the classic 1948 Mexican film Nosotros los pobres wants to become a bracero.

- The 1949 film Border Incident looks at the problem.

- Tom Lehrer's song about George Murphy

See also

Sources

- 2. Handbook of Texas Online[1]

External links

- The Bracero Project

- The 1942 Bracero Agreement (revised April 26, 1943)

- Los Braceros: Strong Arms to Aid the USA - Public Television Program

- Bracero History Archive

- The Bracero Program: Legal Temporary Farmworkers from Mexico, 1942-1964

- Braceros in Oregon Photograph Collection

- Braceros '10% Savings' program documented through archives of Wells Fargo bank

Categories:

- Agriculture in California

- Agricultural labor

- Labor relations in California

- History of labor relations in the United States

- History of the United States (1945–1964)

- Economic history of the United States

- Economic history of Mexico

- Modern Mexico

- History of North America

- Mexican-American history

- Mexico – United States relations

- History of immigration to the United States

- 1942 establishments

- 1942 in Mexico

- 1942 in the United States

- 1964 disestablishments