Charles XI of Sweden

| Charles XI | |

|---|---|

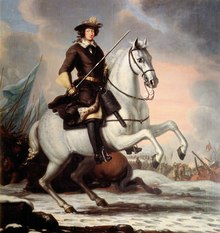

Portrait by David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl, 1689 | |

| King of Sweden Duke of Bremen and Verden | |

| Reign | 13 February 1660[1] – 5 April 1697 |

| Coronation | 28 September 1675 |

| Predecessor | Charles X Gustav |

| Successor | Charles XII |

| Regent | Hedwig Eleonora of Holstein-Gottorp (1660–1672) |

| Born | 24 November 1655 Tre Kronor, Sweden |

| Died | 5 April 1697 (aged 41) Tre Kronor, Sweden |

| Burial | 24 November 1697 Riddarholmen Church, Stockholm |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Palatinate-Zweibrücken |

| Father | Charles X Gustav |

| Mother | Hedwig Eleonora of Holstein-Gottorp |

| Religion | Lutheran |

| Signature | |

Charles XI or Carl (Swedish: Karl XI; 4 December [O.S. 24 November] 1655 – 15 April [O.S. 5 April] 1697)[2] was King of Sweden from 1660 until his death, in a period of Swedish history known as the Swedish Empire (1611–1721).

He was the only son of King Charles X Gustav of Sweden and Hedwig Eleonora of Holstein-Gottorp. His father died when he was four years old, so Charles was educated by his governors until his coronation at the age of seventeen. Soon afterward, he was forced out on military expeditions to secure the recently acquired dominions from Danish troops in the Scanian War. Having successfully fought off the Danes, he returned to Stockholm and engaged in correcting the country's neglected political, financial, and economic situation. He managed to sustain peace during the remaining 20 years of his reign. Changes in finance, commerce, national maritime and land armaments, judicial procedure, church government, and education emerged during this period.[3] Charles XI was succeeded by his only son Charles XII, who made use of the well-trained army in battles throughout Europe.

Though Charles was crowned as Charles XI, he was not the 11th king of Sweden of that name. His father's name (as the 10th) was due to his great-grandfather, King Charles IX of Sweden (1604–1611), having adopted his own numeral by using a mythological History of Sweden. That ancestor was actually the third King Charles.[4] The numbering tradition thus begun still continues, with the present king of Sweden being Carl XVI Gustaf.

Under guardian rule

[edit]

Charles was born in the Stockholm Palace Tre Kronor in November 1655. His father, Charles X of Sweden, had left Sweden in July that year to fight in the war against Poland. After several years of warfare, the king returned in the winter of 1659, gathered his family and the Riksdag of the Estates in Gothenburg. Here he beheld his four-year-old son for the first time. Only a few weeks later, in mid-January 1660, the king fell ill; one month later, he wrote his last will and died.[5]

Charles X Gustav's will and testament left the administration of the Swedish Empire during Charles XI's minority to a regency led by Queen Dowager Hedwig Eleonora as both formal regent and chair of a six-member Regency Council with two votes and a final say over the rest of the council.[6] Per Brahe was one member of the council.[7] In addition, Charles X Gustav left command of the army and a seat on the council to his younger brother, Adolph John I, Count Palatine of Kleeburg.[8] These provisions among others led to the remainder of the council immediately challenging the will. On 14 February, the day after King Charles X's death, Hedwig Eleonora sent a message to the council stating that she knew that they contested the will and that she demanded that it should be respected. The council answered that the will must first be discussed with the parliament, and at the following council in Stockholm on 13 May, the council tried to keep her from attending. The parliament questioned whether it would be good for her health or suitable for a widow to attend council, and that if not, it would be hard to keep sending a messenger to her quarters. Her reply that the council would be allowed to meet without her and only inform her when they considered it necessary was met with satisfaction from the council. Hedwig Eleonora's ostensible indifference to politics came as a great relief to the lords of the guardian government.[8]

His mother, Queen Hedvig Eleonora, remained the formal regent until Charles XI attained his majority on 18 December 1672, but she was careful not to embroil herself in political conflicts.[9] During his first appearances in parliament, Charles spoke to the government through her. He would whisper the questions he had in her ear, and she would ask them aloud and clearly for him.[10] As an adolescent, Charles devoted himself to sports, exercise, and his favourite pastime of bear-hunting. He appeared ignorant of the very rudiments of statecraft and almost illiterate. His main difficulties are now seen as evident signs of dyslexia, a disability that was poorly understood at the time.[11][12][13] According to many contemporary sources, the king was considered poorly educated and therefore not qualified to conduct himself effectively in foreign affairs.[14] Charles was dependent on his mother and advisors to interact with the foreign envoys since he had no foreign language skills apart from German and was ignorant of the world outside Sweden.[15]

Italian writer Lorenzo Magalotti visited Stockholm in 1674 and described the teenage Charles XI as "virtually afraid of everything, uneasy to talk to foreigners, and not daring to look anyone in the face". Another trait was a deep religious devotion: he was God-fearing, frequently prayed kneeling and attended sermons. Magalotti otherwise described the king's main pursuits as hunting, the upcoming war, and jokes.[16][17]

Scanian War

[edit]

The situation in Europe was shaky during this time and Sweden was going through financial problems. Charles XI's guardians decided to negotiate an alliance with France in 1671. This would ensure that Sweden would not be isolated if there was a war, and that the national finances would improve thanks to French subsidies.[18] France directed its aggression against the Dutch in 1672, and by the spring of 1674, Sweden was forced to take part by directing forces towards Brandenburg, under the lead of Karl Gustav Wrangel.[19]

Denmark was an ally of the Habsburg Holy Roman Empire, and it was evident that Sweden was on the verge of yet another war with that country. A remedy was attempted by chancellor Nils Brahe, who traveled to Copenhagen in the spring of 1675 to try to get the Danish princess Ulrika Eleonora of Denmark engaged to the Swedish king. In mid-June 1675, the engagement was officially proclaimed. However, when news arrived of the Swedish defeat at the Battle of Fehrbellin, Danish king Christian V declared war on Sweden that September.[20]

The Swedish Privy Council continued its internal feuds, and the king was forced to rule without them.[21] The 20-year-old king was inexperienced and considered ill-served amidst what has been called the anarchy in the nation. He dedicated autumn in his newly formed camp in Scania to arm the Swedish nation for battle in the Scanian War. The Swedish soldiers in Scania were outnumbered and out-equipped by the Danes. In May 1676, they invaded Scania, taking Landskrona and Helsingborg, then proceeding through Bohuslän towards Halmstad. The King had to grow up quickly. He suddenly found himself alone and under great pressure.[3][22]

Victory at the Battle of Halmstad (17 August 1676), when Charles and his commander-in-chief Simon Grundel-Helmfelt defeated a Danish division, was the king's first glimmer of good luck. Charles continued south through Scania, arriving on the tableland of the flooded Kävlinge River – near Lund – on 11 November. The Danish army commanded by Christian V was positioned on the other side. It was impossible to cross the river and Charles had to wait for weeks until it froze over. This finally happened on 4 December and Charles launched a surprise attack on the Danish forces to fight the Battle of Lund.[3] This was one of the bloodiest engagements of its time. Of the over 20,000 combatants, about 8,000 perished on the battlefield.[3][23][24] All the Swedish commanders showed ability, but the chief glory of the day was attributed to Charles XI and his fighting spirit. The battle proved to be a decisive one for the rule of the Scanian lands and it has been described as the most significant event for Charles' personality. Charles commemorated this date the rest of his life.[25][26]

In the following year, 13,000 men led by Charles routed 12,000 Danes at the Battle of Landskrona. This proved to be the last pitched battle of the war since, in September 1678, Christian V evacuated his army back to Zealand. In 1679, Louis XIV of France dictated the terms of a general pacification, and Charles XI, who is said to have bitterly resented "the insufferable tutelage" of the French king, was forced at last to acquiesce to a peace that managed to leave his empire practically intact.[3] Peace was made with Denmark in the treaties of Fontainebleau (1679) and Lund, and with Brandenburg in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1679).[citation needed]

Post-war actions

[edit]

Charles devoted the rest of his life to avoiding further warfare by gaining larger independence in foreign affairs, while he also promoted economic stabilization and a reorganization of the military. His remaining 20 years on the throne were the longest peacetime of the Swedish Empire (1611–1718).[27]

In the early years, he was assisted by the man who had become his trusted prime-minister, Johan Göransson Gyllenstierna (1635–1680). Some sources say the king was basically dependent on Gyllenstierna.[28] His sudden death in 1680 opened up the road to the monarch, and many men tried to get close to the king to take Gyllenstierna's place.[29]

Financial restoration

[edit]

Sweden's weak economy had suffered during the war and was now in a deep crisis. Charles assembled the Riksdag of the Estates in October 1680. The assembly has been described as one of the most important held by the Riksdag of the Estates.[30] Here, the king finally pushed through the reduction ordeal, something that had been discussed in the Riksdag since 1650. It meant that any land or object previously owned by the crown and lent or given away – including counties, baronies and lordships – could be recovered. It affected many prominent members of the nobility, some of whom were ruined by it. One of them was the former guardian and Lord Chief Justice Magnus De La Gardie, who, among many other Estates, had to return the extravagant 248-room Läckö Castle.[31] The reduction process involved the examination of every title deed in the kingdom, including the dominions, and it resulted in a complete readjustment of the nation's finances.[3][32][33]

Greycoat

[edit]According to Swedish legend, Charles XI travelled around the country dressed as a farmer or simple traveller. In the legend he is referred to as the Greycoat (Swedish: Gråkappan).[34] This was done to discover and identify corruption and oppression against the populace. There are many stories about him arriving in villages looking for corrupt church officials and punishing them. One anecdote tells of him visiting one village with a church in splendid condition and the priest living in poverty. Continuing, the King found in the next village a church in disrepair and a priest living lavishly. The King solved the situation by switching the priests, giving the poor priest the lavish living condition and a church the King was certain he would rebuild. Always followed by a military cortège, Charles toured the country more than other Swedish kings during this era and was famous for the speed at which he travelled, setting many records. The stories of the Greycoat were published in a book by Arvid August Afzelius in the middle of the 19th century.[35][36]

Absolutism

[edit]

Another important decision made during the assembly was that of the Swedish Privy Council. Since 1634, it had been mandatory for the king to take advice from the council. During the Scanian War, the members of the council were engaged in internal feuds, and the king more or less ruled without listening to their advice. At the 1680 assembly, he asked the Estates whether he was still bound to the council, to which the Estates responded with his desired reply: "he was not bound by anyone other than himself" ("envälde"), and thereby the absolute monarchy was formally established in Sweden.[37] The Riksdag of the Estates confirmed his power in 1693 by officially proclaiming that the king was the sole ruler of Sweden.[38]

Military restructuring

[edit]In the 1682 assembly of the Riksdag of the Estates, the king put forth his suggestion for military reform, whereby each of the lands of Sweden were to have 1,200 soldiers at the ready, at all times, and two farms were to provide accommodations for one soldier. His soldiers were known as Caroleans, trained to be skilled and preferring to attack rather than defend. Savagery and looting were strictly forbidden. Soldier huts around the country were the most visible part of the new Swedish allotment system. However, Charles also modernized the military techniques and worked to improve the skills and knowledge of the officers by sending them abroad to study.[39][40]

Charles XI was initially enthusiastic about warfare and combat and he was often portrayed as the soldier-King. In the years after the Scanian War however, during which he personally engaged in the fighting and saw the devastation of war, he would later come to view that war was something better to be avoided if possible. With the recent war in mind he wanted to strengthen the armed forces for a defensive war which he knew would come sooner or later.[41]

The Swedish navy suffered major defeats against Danish-Dutch forces in the Scanian War, revealing deficiencies in organization and supply, and disadvantages in basing the fleet at Stockholm. The navy was bolstered with the founding of an ice-free base at Karlskrona in 1680 which became the mainstay of future naval operations. Today it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[39][40]

Assimilation of the newest territories

[edit]

Charles believed it was very important to assimilate the new Swedish territories of Scania, Blekinge, Halland, in southern Sweden; Bohuslän in western Sweden and Jämtland, in northern Sweden, and the island of Gotland. Some assimilation policies included: the ban of all books written in Danish or Norwegian, thus breaking the promise made at the Treaty of Roskilde; the use of Swedish language in the conduct of sermons; and all new priests and teachers having to come from Sweden.[42][43]

The king had seen bitter resentment from the Scanian peasants during the Scanian War and was particularly tough on that province. The guerrilla Snapphane movement, in northern Scania, had attacked his soldiers and stolen his money. They also had strong support from the local villages. Charles remained suspicious of the Scanian inhabitants throughout his life. He did not allow soldiers from Scania in his Scanian regiment: the 1,200 soldiers that were to be stationed there had to be recruited from more northern provinces. He also advocated rough treatment of the inhabitants and the first Governor-General of Scania, his trusted aide Johan Gyllenstierna (governor-general 1679–1680), was notably brutal in his treatment of the locals. The rule of Rutger von Ascheberg (governor-general 1680–1693), proved more lenient.[42][43]

The assimilation was not as strongly implemented in the German dominions of Swedish Pomerania, Bremen-Verden, and the Baltic dominions (Estonia and Livonia). In Germany, Charles found himself being opposed by the Estates there. He was also bound by the law of the German emperor and the peace treaty. In the Baltic, the power structure was completely different, with a German-descended nobility that used serfs, something that Charles abhorred and wanted to abolish but was unable to. Finally, Kexholm and Ingria were sparsely populated and not of great interest.[42][43]

Church

[edit]Charles was a devoted Lutheran Christian. In February 1686, a church law was put forth on his initiative. The church order declared that the king was ruler of the Church in the same way that he ruled the country and God ruled the world. Attending sermons on Sunday was made obligatory and ordinary people found walking during that time risked arrest. Three years later, he declared it obligatory for all commoners to learn to read a catechism written by archbishop Olov Svebilius and then-bishop Haqvin Spegel so that they would understand the "magnificence of God".[44][45]

Charles encouraged the production of a hymnal (Psalmbok) to be printed and distributed to the churches (completed 1693), and a new printed version of the Bible that was completed in 1703 and named after his successor: Charles XII Bible.[44][45]

Family matters

[edit]

On 6 May 1680, Charles married Ulrika Eleonora of Denmark (1656–1693), daughter of King Frederick III of Denmark (1609–1670). He had previously been engaged to his cousin, Juliana of Hesse-Eschwege, but the engagement was broken after a scandal. Charles and Ulrika were engaged in 1675 in an attempt to smooth over longstanding hostilities, but the Scanian War soon broke out. During the war, Ulrika Eleonora gained a reputation for loyalty to her future home country by exhibiting kindness to Swedish prisoners: she pawned her jewelry, even her engagement ring, to care for the Swedish prisoners of war. Her personal merits and continued charitable acts throughout her tenure endeared her to the Swedish people and eased some of the difficulties brought on by her Danish background.[46] In the peace negotiations between Sweden and Denmark in 1679, the marriage between her and Charles XI was on the agenda, and ratified on 26 September 1679. They married at Skottorp on 6 May 1680 in a hasty ceremony, as Charles prioritized government work over private matters, even a marriage ceremony.[citation needed]

Charles and Ulrika Eleonora were very different. He enjoyed hunting and riding, while she enjoyed reading and art, and is best remembered for her great charitable activity. She was also limited by ill-health and numerous pregnancies. Charles was very active and busy and while Charles was away inspecting his troops or pursuing his pastimes, she was often lonely and sad. The marriage itself, however, is considered a success, with the King and Queen being very fond of each other. As queen, Ulrika Eleonora had little political involvement and was placed in the shadow of her mother-in-law. During "The Great Reversion" to the crown of counties, baronies and large lordships from the nobility, Ulrika tried to speak on the behalf of the people whose property was confiscated by the crown. But the king told her that the reason he had married her was not because he wanted her political advice. Instead, she helped people whose property had been confiscated by secretly compensating them economically from her own budget. However Charles XI's confidence in her grew over time: in 1690, he named her future Regent, should his son succeed him still a minor. Instead Ulrika Eleonora predeceased him by almost four years. At the time of her death she was personally supporting 17,000 people.[47]

It is said that on his death bed, Charles XI admitted to his mother that he hadn't been happy since Ulrika Eleonora's death.[48]

The marriage produced seven children, of whom only three outlived Charles:[49]

- Hedwig Sophia (1681–1708), duchess of Holstein-Gottorp and grandmother of Tsar Peter III;

- Charles XII (1682–1718), who succeeded him to the throne; he had no issue

- Gustav (1683–1685)

- Ulric (1684–1685)

- Frederick (1685–1685)

- Charles Gustav (1686–1687)

- Ulrika Eleonora ("the younger", 1688–1741), who succeeded her brother on the Swedish throne; no issue

Ulrika Eleonora (the elder) was sickly, and the many child births eventually broke her. When she became seriously ill, in 1693, Charles finally dedicated his time and care to her. Her death in July that year shook him deeply and he never fully recovered.[3][48] Her infant son Ulric (1684–1685) had been given Ulriksdal Palace, which was renamed for him (Ulric's Dale).[50]

Death

[edit]

Charles XI had complained of stomach pains since 1694. In the summer of 1696, he asked his doctors for an opinion on the pain as it had continuously become worse, but they had no viable cure or treatment for it. He continued to perform his duties as usual, but, in February 1697, the pains became too severe for him to cope and he returned to Stockholm where the doctors discovered he had a large, hard lump in his stomach. At this point there was little the doctors could do except alleviate the King's pain as best they could. Charles XI died on 5 April 1697, at the age of 41. An autopsy showed that the King had developed cancer and that it had spread through his entire abdominal cavity.[51]

Legacy

[edit]

Charles XI has sometimes been described in Sweden as the greatest of all the Swedish kings, except for Gustavus II Adolphus, unduly eclipsed by his father and his son.[3] In the first half of the 20th century, the view of him changed and he was regarded as dependent, uncertain, and easily influenced by others.[52] In the most recent book, Rystad's biography from 2003, the king is again characterized as a strong-willed shaper of Sweden through economic reforms and achievement of financial and military stability and strength.[53]

Charles XI was commemorated on the previous 500-kronor bill. His portrait is taken from one of Ehrenstrahl's paintings, possibly the one displayed on this page. The king is pictured on the bill since the Bank of Sweden was founded in 1668, during Charles' reign.[54]

The fortified town of Carlsburg near Bremen, at the site of modern Bremerhaven, was named after Charles XI. The Swedish town of Karlskrona, built during his reign to host the primary navy base in southern Sweden, which it remains to this day, is also named after him.[citation needed]

Charles's Church in Tallinn, Estonia, is dedicated to Charles XI.[citation needed] The recognition of his sores and corpse didn't show the incorruptibility that medieval hagiographers believed to be a sign of Christian sainthood. In 1697 the same belief caused Charles's subjects to ask if "God had put the illness inside the king...to punish the people or Charles." Two years later, the course of events that highlighted the crisis was of the absolutism itself.[55]

Ancestors

[edit]| Ancestors of Charles XI of Sweden |

|---|

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Karl XI". Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 13 (2nd ed.). 1910. p. 962.

- ^ This article uses the Julian calendar, which was used in Sweden until 1700 (see Swedish calendar for more information). In the Gregorian calendar, Charles was born 4 December 1655 and died 15 April 1697.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bain 1911b

- ^ Article Karl Archived 30 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine in Nordisk familjebok

- ^ Åberg (1958)

- ^ Granlund 2004, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Granlund 2004, p. 59.

- ^ a b Lundh-Eriksson, Nanna (1947). Hedvig Eleonora (in Swedish). Wahlström & Widstrand.

- ^ Rystad (2003), p. 26

- ^ Herman Lindqvist: Historien om Sverige: Storhet och Fall (History of Sweden: Greatness and fall) (in Swedish)

- ^ Nationalencyclopedin, article Karl XII

- ^ Rystad (2003), p. 23

- ^ Åberg (1958) gives examples: he would start with the last letter when reading words, and would spell faton instead of afton, etc.

- ^ Upton, Anthony F. (1998). Charles XI and Swedish Absolutism, 1660–1697. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-57390-4, p. 91: "There was a widespread contemporary impression that the king was poorly qualified and ineffective in foreign affairs [...] The Danish minister, M. Scheel, reported to his king how Charles XI seemed embarrassed by questions, kept his eyes down and was taciturn [...] The French diplomat, Jean Antoine de Mesmes, comte d'Avaux, described him as 'a prince with few natural talents', so obsessed with getting money out of his subjects that he 'does not concern himself much with foreign affairs'. The Dane, Jens Juel, made a similar comment."

- ^ Upton, p. 91.

- ^ Rystad (2003) p. 37

- ^ Åberg (1958), pp. 63–65

- ^ Åberg (1959) pp. 50–53

- ^ Åberg, p. 66

- ^ Åberg (1958), pp. 71–72

- ^ Åberg (1958), pp. 72–74

- ^ Åberg (1958), pp. 75–76

- ^ Åberg (1958), pp. 77–79

- ^ Rystad (2003), p. 95, estimates that 8,000–9,000 men fell out of 20,000

- ^ Åberg (1958) p. 81

- ^ Rystad (2003) p. 97

- ^ Nationalencyklopedin, article Karl XI

- ^ Åberg (1958), pp. 106–107

- ^ Rystad (2003) p. 165

- ^ Rystad (2003), p. 167

- ^ Rystad (2003) p. 181

- ^ Åberg (1958), pp. 93–94

- ^ Trager, James (1979). The People's Chronology. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. p. 256. ISBN 0-03-017811-8.

- ^ Lars O. Lagerqvist in Sverige och dess regenter under 1000 år ISBN 91-0-075007-7 p. 185

- ^ Libris Archived 20 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine listing at Swedish National Library

- ^ Rystad, Göran (2001). Karl XI: en biografi (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska media. p. 255. ISBN 978-91-89442-27-6.

- ^ Åberg (1958), p. 111

- ^ Åberg (1958), p. 190

- ^ a b Åberg (1958) pp. 125–134

- ^ a b Rystad (2003), pp. 241–265

- ^ Rystad, Göran (2001). Karl XI: en biografi (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska media. p. 240. ISBN 978-91-89442-27-6.

- ^ a b c Åberg (1958), pp. 135–146

- ^ a b c Rystad (2003) pp. 307–344

- ^ a b Åberg (1958), pp. 157–166

- ^ a b Rystad (2003) pp. 345–357

- ^ Nanna Lundh-Eriksson (1947). Hedvig Eleonora. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand. ISBN (Swedish)

- ^ Ulrika Eleonora of Denmark in CF Bricka, Danish biographical encyclopaedia (1st edition, 1904)

- ^ a b Rystad (2003), pp.287–289

- ^ "Karl XI". Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Vol. 13 (2nd ed.). 1910. pp. 967–968.

- ^ Ulf Sundberg ln Kungliga släktband ISBN 9185057487 p 137

- ^ Rystad (2003), pp. 368–369

- ^ Back-cover of Åberg (1958)

- ^ Back-cover of Rystad (2003)

- ^ (in Swedish) 500-kronorssedeln Archived 8 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine – From Bank of Sweden official site. Accessed 2 September 2008

- ^ Sennefelt, Karin (22 December 2020). A Pathology of Sacral Kingship: Putrefaction in the Body of Charles XI of Sweden. Oxford University Press. pp. 83–117. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtaa025. ISSN 1477-464X. OCLC 8620538229. Archived from the original on 26 December 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bain 1911a.

- ^ a b Dahlgren, Stellan (1971). "Hedvig Eleonora". Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (in Swedish). Vol. 18. p. 512.

- ^ a b Kromnow, Åke (1975). "Johan Kasimir". Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (in Swedish). Vol. 20. p. 204.

- ^ a b Kromnow, Åke (1977). "Katarina". Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (in Swedish). Vol. 21. p. 1.

- ^ a b Kellenbenz, Hermann (1961), "Friedrich III.", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 5, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 583–584; (full text online)

- ^ a b "Marie Elizabeth of Saxony (1610–1684)". Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Gale. 2002 – via Encyclopedia.com.

References

[edit]- Åberg, Alf: Karl XI, Wahlström & Widstrand 1958 (reprinted by ScandBook, Falun 1994, ISBN 91-46-16623-8 )

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911a). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 927–929.

- Granlund, Lis (2004). "Queen Hedwig Eleonora of Sweden: Dowager, Builder, and Collector". In Campbell Orr, Clarissa (ed.). Queenship in Europe 1660–1815: The Role of the Consort. Cambridge University Press. pp. 56–76. ISBN 0-521-81422-7.

- Lindqvist, Herman: Historien om Sverige

- Roberts, Michael. "Charles XI" History 50:169 (1965): 160–192.

- Rystad, Göran: Karl XI / En biografi, AiT Falun AB 2001. ISBN 91-89442-27-X

- Upton, Anthony F. Charles XI and Swedish Absolutism, 1660–1697. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-57390-4.

Attribution

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911b). "Charles XI.". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 929.

Further reading

[edit]- Åberg, A., "The Swedish army from Lützen to Narva", in Michael Roberts (ed.), Sweden's Age of Greatness, 1632–1718 (1973).

External links

[edit] Media related to Charles XI of Sweden at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charles XI of Sweden at Wikimedia Commons- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Charles XI of Sweden at DigitaltMuseum

- 1655 births

- 1697 deaths

- 17th-century Swedish monarchs

- People from Stockholm

- House of Palatinate-Zweibrücken

- House of Wittelsbach

- Dukes of Bremen and Verden

- Knights of the Garter

- Child monarchs

- Counts Palatine of Zweibrücken

- Deaths from stomach cancer in Sweden

- Swedish monarchs of German descent

- Burials at Riddarholmen Church

- People of the Scanian War

- Sons of kings