Chinese art

Chinese art is visual art that, whether ancient or modern, originated in or is practiced in China or by Chinese artists. The Chinese art in the Republic of China (Taiwan) and that of overseas Chinese can also be considered part of Chinese art where it is based in or draws on Chinese heritage and Chinese culture. Early "stone age art" dates back to 10,000 BC, mostly consisting of simple pottery and sculptures. After this early period Chinese art, like Chinese history, is typically classified by the succession of ruling dynasties of Chinese emperors, most of which lasted several hundred years.

Chinese art has arguably the oldest continuous tradition in the world, and is marked by an unusual degree of continuity within, and consciousness of, that tradition, lacking an equivalent to the Western collapse and gradual recovery of classical styles. The media that have usually been classified in the West since the Renaissance as the decorative arts are extremely important in Chinese art, and much of the finest work was produced in large workshops or factories by essentially unknown artists, especially in the field of Chinese porcelain. Much of the best work in ceramics, textiles and other techniques was produced over a long period by the various Imperial factories or workshops, which as well as being used by the court was distributed internally and abroad on a huge scale to demonstrate the wealth and power of the Emperors. In contrast, the tradition of ink wash painting, practiced mainly by scholar-officials and court painters especially of landscapes, flowers, and birds, developed aesthetic values depending on the individual imagination of and objective observation by the artist that are similar to those of the West, but long pre-dated their development there. After contacts with Western art became increasingly important from the 19th century onwards, in recent decades China has participated with increasing success in worldwide contemporary art.

Painting

Traditional Chinese painting involves essentially the same techniques as Chinese calligraphy and is done with a brush dipped in black or colored ink; oils are not used. As with calligraphy, the most popular materials on which paintings are made of paper and silk. The finished work can be mounted on scrolls, such as hanging scrolls or handscrolls. Traditional painting can also be done on album sheets, walls, lacquerware, folding screens, and other media.

The two main techniques in Chinese painting are:

- Gong-bi (工筆), meaning "meticulous", uses highly detailed brushstrokes that delimits details very precisely. It is often highly coloured and usually depicts figural or narrative subjects. It is often practised by artists working for the royal court or in independent workshops. Bird-and-flower paintings were often in this style.

- Ink and wash painting, in Chinese Shui-mo or (水墨[2]) also loosely termed watercolour or brush painting, and also known as "literati painting", as it was one of the "Four Arts" of the Chinese Scholar-official class.[3] In theory this was an art practised by gentlemen, a distinction that begins to be made in writings on art from the Song dynasty, though in fact the careers of leading exponents could benefit considerably.[4] This style is also referred to as "xie yi" (寫意) or freehand style.

Artists from the Han (202 BC) to the Tang (618–906) dynasties mainly painted the human figure. Much of what is known of early Chinese figure painting comes from burial sites, where paintings were preserved on silk banners, lacquered objects, and tomb walls. Many early tomb paintings were meant to protect the dead or help their souls get to paradise. Others illustrated the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius, or showed scenes of daily life. Most Chinese portraits showed a formal full-length frontal view, and were used in the family in ancestor veneration. Imperial portraits were more flexible, but were generally not seen outside the court, and portraiture formed no part of Imperial propaganda, as in other cultures.

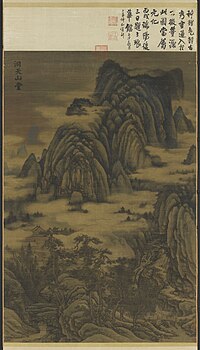

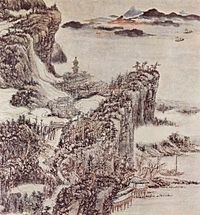

Many critics consider landscape to be the highest form of Chinese painting. The time from the Five Dynasties period to the Northern Song period (907–1127) is known as the "Great age of Chinese landscape". In the north, artists such as Jing Hao, Li Cheng, Fan Kuan, and Guo Xi painted pictures of towering mountains, using strong black lines, ink wash, and sharp, dotted brushstrokes to suggest rough rocks. In the south, Dong Yuan, Juran, and other artists painted the rolling hills and rivers of their native countryside in peaceful scenes done with softer, rubbed brushwork. These two kinds of scenes and techniques became the classical styles of Chinese landscape painting.

-

Traditional Chinese portrait Hanging scroll portrait on silk

-

‘Pink and White Lotus’, 14th century bird-and-flower painting

-

The deity Zhong Kui, the Demon Queller

-

Chen Cheng-po, 1933, canvas oil painting, Collection of Taiwan Museum of Fine Art

-

Wood, Bamboo, and Elegant Stone, Ni Zan, 1360s-1370s, Palace Museum

Sculpture

Chinese ritual bronzes from the Shang and Western Zhou Dynasties come from a period of over a thousand years from c. 1500, and have exerted a continuing influence over Chinese art. They are cast with complex patterned and zoomorphic decoration, but avoid the human figure, unlike the huge figures only recently discovered at Sanxingdui.[5] The spectacular Terracotta Army was assembled for the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China from 221–210 BC, as a grand imperial version of the figures long placed in tombs to enable the deceased to enjoy the same lifestyle in the afterlife as when alive, replacing actual sacrifices of very early periods. Smaller figures in pottery or wood were placed in tombs for many centuries afterwards, reaching a peak of quality in the Tang Dynasty.[6]

Native Chinese religions do not usually use cult images of deities, or even represent them, and large religious sculpture is nearly all Buddhist, dating mostly from the 4th to the 14th century, and initially using Greco-Buddhist models arriving via the Silk Road. Buddhism is also the context of all large portrait sculpture; in total contrast to some other areas in medieval China even painted images of the emperor were regarded as private. Imperial tombs have spectacular avenues of approach lined with real and mythological animals on a scale matching Egypt, and smaller versions decorate temples and palaces.[7] Small Buddhist figures and groups were produced to a very high quality in a range of media,[8] as was relief decoration of all sorts of objects, especially in metalwork and jade.[9] Sculptors of all sorts were regarded as artisans and very few names are recorded.[10]

-

Pottery tomb figure of dancing girl, Han Dynasty (202 BC-220 AD)

-

Northern Wei Dynasty Maitreya (386–534)

-

Seated Buddha, Tang Dynasty ca. 650.

-

The Leshan Giant Buddha, Tang Dynasty, completed in 803.

-

Portrait of monk, Song Dynasty, 11th century

-

A wooden Bodhisattva from the Song Dynasty (960–1279)

-

Chinese jade Cup with Dragon Handles, 12th century

Pottery

Chinese ceramic ware shows a continuous development since the pre-dynastic periods, and is one of the most significant forms of Chinese art. China is richly endowed with the raw materials needed for making ceramics. The first types of ceramics were made during the Palaeolithic era, and in later periods range from construction materials such as bricks and tiles, to hand-built pottery vessels fired in bonfires or kilns, to the sophisticated Chinese porcelain wares made for the imperial court. Most later Chinese ceramics, even of the finest quality, were made on an industrial scale, thus very few individual potters or painters are known. Many of the most renowned workshops were owned by or reserved for the Emperor, and large quantities of ceramics were exported as diplomatic gifts or for trade from an early date.

-

Wine jar, Western Zhou Dynasty (1050 BC-771 BC)

-

Dish with underglazed blue and overglazed red design of clouds and dragons, Jingdezhen ware, Yongzheng period (1723-1735), Qing dynasty, Shanghai Museum

-

Sancai glazed ceramic horse, Tang Dynasty of China, 7th-8th Century, Musée Guimet

-

Blue underglaze statue of a man with his pipe, from Jingdezhen, Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)

-

Ming dynasty Xuande mark and period (1426–35) imperial blue and white vase. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 明宣德 景德鎮窯青花貫耳瓶, 纽约大都博物馆

Decorative arts

As well as porcelain, a wide range of materials that were more valuable were worked and decorated with great skill for a range of uses or just for display.[9] Chinese jade was attributed with magical powers, and was used in the Stone and Bronze Ages for large and impractical versions of everyday weapons and tools, as well as the bi disks and cong vessels.[11] Later a range of objects and small sculptures were carved in jade, a difficult and time-consuming technique. Bronze, gold and silver, rhinoceros horn, Chinese silk, ivory, lacquer, cloisonne enamel and many other materials had specialist artists working in them.

Folding screen(Chinese: 屏風; pinyin: píngfēng) is also a form of decorative art in China. And the folding screen itself was often decorated with beautiful art, major themes included mythology, scenes of palace life, and nature.There are different kinds of materials in making folding screens, such as wood panel, paper and silk. Folding screens were considered ideal ornaments for many painters to display their paintings and calligraphy on.[12][13] Many artists painted on paper or silk and applied it onto the folding screen.[12] There were two distinct artistic folding screens mentioned in historical literature of the era.

Historical development to 221 BC

Neolithic pottery

Early forms of art in China are found in the Neolithic Yangshao culture, which dates back to the 6th millennium BC. Archeological findings such as those at the Banpo have revealed that the Yangshao made pottery; early ceramics were unpainted and most often cord-marked. The first decorations were fish and human faces, but these eventually evolved into symmetrical-geometric abstract designs, some painted.

The most distinctive feature of Yangshao culture was the extensive use of painted pottery, especially human facial, animal, and geometric designs. Unlike the later Longshan culture, the Yangshao culture did not use pottery wheels in pottery making. Excavations have found that children were buried in painted pottery jars.

Jade culture

The Liangzhu culture was the last Neolithic Jade culture in the Yangtze River Delta and was spaced over a period of about 1,300 years. The Jade from this culture is characterized by finely worked, large ritual jades such as Cong cylinders, Bi discs, Yue axes and also pendants and decorations in the form of chiseled open-work plaques, plates and representations of small birds, turtles and fish. The Liangzhu Jade has a white, milky bone-like aspect due to its Tremolite rock origin and influence of water-based fluids at the burial sites.

Bronze casting

The Bronze Age in China began with the Xia Dynasty. Examples from this period have been recovered from ruins of the Erlitou culture, in Shanxi, and include complex but unadorned utilitarian objects. In the following Shang Dynasty more elaborate objects, including many ritual vessels, were crafted. The Shang are remembered for their bronze casting, noted for its clarity of detail. Shang bronzesmiths usually worked in foundries outside the cities to make ritual vessels, and sometimes weapons and chariot fittings as well. The bronze vessels were receptacles for storing or serving various solids and liquids used in the performance of sacred ceremonies. Some forms such as the ku and jue can be very graceful, but the most powerful pieces are the ding, sometimes described as having the an "air of ferocious majesty."

It is typical of the developed Shang style that all available space is decorated, most often with stylized forms of real and imaginary animals. The most common motif is the taotie, which shows a mythological being presented frontally as though squashed onto a horizontal plane to form a symmetrical design. The early significance of taotie is not clear, but myths about it existed around the late Zhou Dynasty. It was considered to be variously a covetous man banished to guard a corner of heaven against evil monsters; or a monster equipped with only a head which tries to devour men but hurts only itself.

The function and appearance of bronzes changed gradually from the Shang to the Zhou. They shifted from been used in religious rites to more practical purposes. By the Warring States period, bronze vessels had become objects of aesthetic enjoyment. Some were decorated with social scenes, such as from a banquet or hunt; whilst others displayed abstract patterns inlaid with gold, silver, or precious and semiprecious stones.

Shang bronzes became appreciated as works of art from the Song Dynasty, when they were collected and prized not only for their shape and design but also for the various green, blue green, and even reddish patinas created by chemical action as they lay buried in the ground. The study of early Chinese bronze casting is a specialized field of art history.

-

Black eggshell pottery of the Longshan culture (c. 3000–2000 BC)

-

A Zhou Dynasty bronze musical bell

Chu and Southern culture

A rich source of art in early China was the state of Chu, which developed in the Yangtze River valley. Excavations of Chu tombs have found painted wooden sculptures, jade disks, glass beads, musical instruments, and an assortment of lacquerware. Many of the lacquer objects are finely painted, red on black or black on red. A site in Changsha, Hunan province, has revealed some of the oldest paintings on silk discovered to date.

Early Imperial China (221 BC–AD 220)

Qin sculpture

The Terracotta Army, inside the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor, consists of more than 7,000 life-size tomb terra-cotta figures of warriors and horses buried with the self-proclaimed first Emperor of Qin (Qin Shi Huang) in 210–209 BC. The figures were painted before being placed into the vault. The original colors were visible when the pieces were first unearthed. However, exposure to air caused the pigments to fade, so today the unearthed figures appear terracotta in color. The figures are in several poses including standing infantry and kneeling archers, as well as charioteers with horses. Each figure's head appears to be unique, showing a variety of facial features and expressions as well as hair styles.

Pottery

Porcelain is made from a hard paste made of the clay kaolin and a feldspar called petuntse, which cements the vessel and seals any pores. China has become synonymous with high-quality porcelain. Most china pots comes from the city of Jingdezhen in China's Jiangxi province. Jingdezhen, under a variety of names, has been central to porcelain production in China since at least the early Han Dynasty.

The most noticeable difference between porcelain and the other pottery clays is that it "wets" very quickly (that is, added water has a noticeably greater effect on the plasticity for porcelain than other clays), and that it tends to continue to "move" longer than other clays, requiring experience in handling to attain optimum results. During medieval times in Europe, porcelain was very expensive and in high demand for its beauty. TLV mirrors also date from the Han dynasty.

Han art

The Han Dynasty was known for jade burial suits. One of the earliest known depictions of a landscape in Chinese art comes from a pair of hollow-tile door panels from a Western Han Dynasty tomb near Zhengzhou, dated 60 BC.[14] A scene of continuous depth recession is conveyed by the zigzag of lines representing roads and garden walls, giving the impression that one is looking down from the top of a hill.[14] This artistic landscape scene was made by the repeated impression of standard stamps on the clay while it was still soft and not yet fired.[14] However, the oldest known landscape art scene tradition in the classical sense of painting is a work by Zhan Ziqian of the Sui Dynasty (581–618).

-

A gilt bronze lamp with a shutter, in the shape of a maidservant, from the Western Han Dynasty, 2nd century BC

-

Two gentlemen engrossed in conversation while two others look on, a painting on a ceramic tile from a tomb near Luoyang, Henan province, dated to the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD)

Period of division (220–581)

Influence of Buddhism

Buddhism arrived in China around the 1st century AD (although there are some traditions about a monk visiting China during Asoka's reign), and through to the 8th century it became very active and creative in the development of Buddhist art, particularly in the area of statuary. Receiving this distant religion, China soon incorporated strong Chinese traits in its artistic expression.

In the fifth to sixth century the Northern Dynasties, rather removed from the original sources of inspiration, tended to develop rather symbolic and abstract modes of representation, with schematic lines. Their style is also said to be solemn and majestic. The lack of corporeality of this art, and its distance from the original Buddhist objective of expressing the pure ideal of enlightenment in an accessible, realistic manner, progressively led to a research towards more naturalism and realism, leading to the expression of Tang Buddhist art.

Calligraphy

In ancient China, painting and calligraphy were the most highly appreciated arts in court circles and were produced almost exclusively by amateurs, aristocrats and scholar-officials who alone had the leisure to perfect the technique and sensibility necessary for great brushwork. Calligraphy was thought to be the highest and purest form of painting. The implements were the brush pen, made of animal hair, and black inks, made from pine soot and animal glue. Writing as well as painting was done on silk. But after the invention of paper in the 1st century, silk was gradually replaced by the new and cheaper material. Original writings by famous calligraphers have been greatly valued throughout China's history and are mounted on scrolls and hung on walls in the same way that paintings are.

Wang Xizhi was a famous Chinese calligrapher who lived in the 4th century AD. His most famous work is the Lanting Xu, the preface of a collection of poems written by a number of poets when gathering at Lan Ting near the town of Shaoxing in Zhejiang province and engaging in a game called "qu shui liu shang".

Wei Shuo was a well-known calligrapher of Eastern Jin Dynasty who established consequential rules about the Regular Script. Her well-known works include Famous Concubine Inscription (名姬帖 Ming Ji Tie) and The Inscription of Wei-shi He'nan (衛氏和南帖 Wei-shi He'nan Tie).

Painting

Gu Kaizhi is a celebrated painter of ancient China born in Wuxi. He wrote three books about painting theory: On Painting (畫論), Introduction of Famous Paintings of Wei and Jin Dynasties (魏晉勝流畫讚) and Painting Yuntai Mountain (畫雲臺山記). He wrote, "In figure paintings the clothes and the appearances were not very important. The eyes were the spirit and the decisive factor."

Three of Gu's paintings still survive today. They are "Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies", "Nymph of the Luo River" (洛神賦), and "Wise and Benevolent Women".

There are other examples of Jin Dynasty painting from tombs. This includes the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, painted on a brick wall of a tomb located near modern Nanjing and now found in the Shaanxi Provincial Museum. Each of the figures are labeled and shown either drinking, writing, or playing a musical instrument. Other tomb paintings also depict scenes of daily life, such as men plowing fields with teams of oxen.

-

Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, an Eastern Jin tomb painting from Nanjing, now located in the Shaanxi Provincial Museum.

-

Northern Wei wall murals and painted figurines from the Yungang Grottoes, dated 5th to 6th centuries.

-

A scene of two horseback riders from a wall painting in the tomb of Lou Rui at Taiyuan, Shanxi, Northern Qi Dynasty (550–577)

The Sui and Tang dynasties (581–960)

Buddhist architecture and sculpture

Following a transition under the Sui Dynasty, Buddhist sculpture of the Tang evolved towards a markedly lifelike expression. As a consequence of the Dynasty's openness to foreign trade and influences through the Silk Road, Tang dynasty Buddhist sculpture assumed a rather classical form, inspired by the Greco-Buddhist art of Central Asia.

However, foreign influences came to be negatively perceived towards the end of the Tang dynasty. In the year 845, the Tang emperor Wu-Tsung outlawed all "foreign" religions (including Christian Nestorianism, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism) in order to support the indigenous Taoism. He confiscated Buddhist possessions and forced the faith to go underground, therefore affecting the ulterior development of the religion and its arts in China.

Most wooden Tang sculptures have not survived, though representations of the Tang international style can still be seen in Nara, Japan. The longevity of stone sculpture has proved much greater. Some of the finest examples can be seen at Longmen, near Luoyang, Yungang near Datong, and Bingling Temple, in Gansu.

One of the most famous Buddhist Chinese pagodas is the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, built in 652 AD.

-

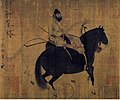

A Man Herding Horses, by Han Gan (706–783 AD), Tang Dynasty original.

-

Tang Dynasty painting from Dunhuang.

Painting

Beginning in the Tang dynasty (618–907), the primary subject matter of painting was the landscape, known as shanshui (mountain water) painting. In these landscapes, usually monochromatic and sparse, the purpose was not to reproduce exactly the appearance of nature but rather to grasp an emotion or atmosphere so as to catch the "rhythm" of nature.

Painting in the traditional style involved essentially the same techniques as calligraphy and was done with a brush dipped in black or colored ink; oils were not used. As with calligraphy, the most popular materials on which paintings were made were paper and silk. The finished works were then mounted on scrolls, which could be hung or rolled up. Traditional painting was also done in albums, on walls, lacquer work, and in other media.

Dong Yuan was an active painter in the Southern Tang Kingdom. He was known for both figure and landscape paintings, and exemplified the elegant style which would become the standard for brush painting in China over the next 900 years. As with many artists in China, his profession was as an official where he studied the existing styles of Li Sixun and Wang Wei. However, he added to the number of techniques, including more sophisticated perspective, use of pointillism and crosshatching to build up vivid effect.

Zhan Ziqian was a painter during the Sui Dynasty. His only painting in existence is Strolling About In Spring arranged mountains perspectively. Because the first pure scenery paintings of Europe emerged after the 17th century, Strolling About In Spring may well be the first scenery painting of the world.

The Song and Yuan dynasties (960–1368)

Song painting

During the Song dynasty (960–1279), landscapes of more subtle expression appeared; immeasurable distances were conveyed through the use of blurred outlines, mountain contours disappearing into the mist, and impressionistic treatment of natural phenomena. Emphasis was placed on the spiritual qualities of the painting and on the ability of the artist to reveal the inner harmony of man and nature, as perceived according to Taoist and Buddhist concepts.

Liang Kai was a Chinese painter who lived in the 13th century (Song Dynasty). He called himself "Madman Liang," and he spent his life drinking and painting. Eventually, he retired and became a Zen monk. Liang is credited with inventing the Zen school of Chinese art. Wen Tong was a painter who lived in the 11th century. He was famous for ink paintings of bamboo. He could hold two brushes in one hand and paint two different distanced bamboos simultaneously. He did not need to see the bamboo while he painted them because he had seen a lot of them.

Zhang Zeduan was a notable painter for his horizontal Along the River During Qingming Festival landscape and cityscape painting. It has been quoted as "China's Mona Lisa" and has had many well-known remakes throughout Chinese history.[15] Other famous paintings include The Night Revels of Han Xizai, originally painted by the Southern Tang artist Gu Hongzhong in the 10th century, while the well-known version of his painting is a 12th-century remake of the Song Dynasty. This is a large horizontal handscroll of a domestic scene showing men of the gentry class being entertained by musicians and dancers while enjoying food, beverage, and wash basins provided by maidservants. In 2000, the modern artist Wang Qingsong created a parody of this painting with a long, horizontal photograph of people in modern clothing making similar facial expressions, poses, and hand gestures as the original painting.

-

Song Dynasty ding-ware porcelain bottle with iron pigment under a transparent colorless glaze, 11th century.

-

Playing Children, by Song artist Su Hanchen, c. 1150 AD.

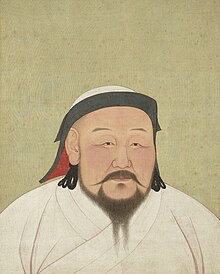

Yuan painting

With the fall of the Song dynasty in 1279, and the subsequent dislocation caused by the establishment of the Yuan dynasty by the Mongol conquerors, many court and literary artists retreated from social life, and returned to nature, through landscape paintings, and by renewing the "blue and green" style of the Tang era.[16]

Wang Meng was one such painter, and one of his most famous works is the Forest Grotto. Zhao Mengfu was a Chinese scholar, painter and calligrapher during the Yuan Dynasty. His rejection of the refined, gentle brushwork of his era in favor of the cruder style of the 8th century is considered to have brought about a revolution that created the modern Chinese landscape painting. There was also the vivid and detailed works of art by Qian Xuan (1235–1305), who had served the Song court, and out of patriotism refused to serve the Mongols, instead turning to painting. He was also famous for reviving and reproducing a more Tang Dynasty style of painting.

The later Yuan dynasty is characterized by the work of the so-called "Four Great Masters". The most notable of these was Huang Gongwang (1269–1354) whose cool and restrained landscapes were admired by contemporaries, and by the Chinese literati painters of later centuries. Another of great influence was Ni Zan (1301–1374), who frequently arranged his compositions with a strong and distinct foreground and background, but left the middle-ground as an empty expanse. This scheme was frequently to be adopted by later Ming and Qing dynasty painters.[16]

Late imperial China (1368–1911)

Ming painting

Under the Ming dynasty, Chinese culture bloomed. Narrative painting, with a wider color range and a much busier composition than the Song paintings, was immensely popular during the time.

Wen Zhengming (1470–1559) developed the style of the Wu school in Suzhou, which dominated Chinese painting during the 16th century.[17]

European culture began to make an impact on Chinese art during this period. The Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci visited Nanjing with many Western artworks, which were influential in showing different techniques of perspective and shading.[18]

Early Qing painting

The early Qing dynasty developed in two main strands: the Orthodox school, and the Individualist painters, both of which followed the theories of Dong Qichang, but emphasizing very different aspects.[19]

The "Four Wangs", including Wang Jian (1598–1677) and Wang Shimin (1592–1680), were particularly renowned in the Orthodox school, and sought inspiration in recreating the past styles, especially the technical skills in brushstrokes and calligraphy of ancient masters. The younger Wang Yuanqi (1642–1715) ritualized the approach of engaging with and drawing inspiration from a work of an ancient master. His own works were often annotated with his theories of how his painting relates to the master's model.[20]

The Individualist painters included Bada Shanren (1626–1705) and Shitao (1641–1707). They drew more from the revolutionary ideas of transcending the tradition to achieve an original individualistic styles; in this way they were more faithfully following the way of Dong Qichang than the Orthodox school (who were his official direct followers.)[21]

As the techniques of color printing were perfected, illustrated manuals on the art of painting began to be published. Jieziyuan Huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden), a five-volume work first published in 1679, has been in use as a technical textbook for artists and students ever since.

Late Qing Art

Nianhua were a form of colored woodblock prints in China, depicting images for decoration during the Chinese New Year. In the 19th century Nianhua were used as news mediums.

Shanghai School

The Shanghai School is a very important Chinese school of traditional arts during the Qing Dynasty and the 20th century. Under efforts of masters from this school, traditional Chinese art reached another climax and continued to the present in forms of "Chinese painting" (中國畫), or guohua (國畫) for short. The Shanghai School challenged and broke the literati tradition of Chinese art, while also paying technical homage to the ancient masters and improving on existing traditional techniques. Members of this school were themselves educated literati who had come to question their very status and the purpose of art, and had anticipated the impending modernization of Chinese society. In an era of rapid social change, works from the Shanghai School were widely innovative and diverse, and often contained thoughtful yet subtle social commentary. The best known figures from this school are Ren Xiong, Ren Bonian, Zhao Zhiqian, Wu Changshuo, Sha Menghai, Pan Tianshou, Fu Baoshi, He Tianjian, and Xie Zhiliu. Other well-known painters include Wang Zhen, XuGu, Zhang Xiong, Hu Yuan, and Yang Borun.

New China art (1912–1949)

Transformation

With the end of the last dynasty in China, the New Culture Movement began and defied all facets of traditionalism. A new breed of 20th century cultural philosophers like Xiao Youmei, Cai Yuanpei, Feng Zikai and Wang Guangqi wanted Chinese culture to modernize and reflect the New China. The Chinese Civil War would cause a drastic split between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party of China. Following was the Second Sino-Japanese War in particular the Battle of Shanghai would leave the major cultural art center borderline to a humanitarian crisis.

Painting

Ong Schan Tchow (Chinese: 翁占秋) (1900–1945), artist and friend of Cai Yuanpei accomplished the subtle integration of Western art techniques and perspectives into traditional Chinese painting. Ong was one of the first few batches of Chinese scholars and artists who studied in France in the early 20th Century.

Western style oil painting was introduced to China by painters such as Xiao Tao Sheng. Another important influential artist in the 1940s was Tai Ping Meijing who incorporated nature in all his art and mixed traditional Asian art with realism.

Communist and socialist art (1950-1980s)

Selective art decline

The Communist Party of China would have full control of the government with Mao Zedong heading the People's Republic of China. If the art was presented in a manner that favored the government, the artists were heavily promoted. Vice versa, any clash with communist party beliefs would force the artists to become farmers via "re-education" processes under the regime. The peak era of governmental control came under the Cultural Revolution. The most notable event was the Destruction of the Four Olds, which had major consequences for pottery, paintings, literary art, architecture and countless others.[citation needed]

Painting

Artists were encouraged to employ socialist realism. Some Soviet Union socialist realism was imported without modification, and painters were assigned subjects and expected to mass-produce paintings. This regimen was considerably relaxed in 1953, and after the Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1956–57, traditional Chinese painting experienced a significant revival. Along with these developments in professional art circles, there was a proliferation of peasant art depicting everyday life in the rural areas on wall murals and in open-air painting exhibitions. Notable modern Chinese painters include Huang Binhong, Qi Baishi, Xu Beihong, Chang Ta Chien, Pan Tianshou, Wu Changshi, Fu Baoshi, Wang Kangle and Zhang Chongren.

Redevelopment (Mid-1980s – 1990s)

Contemporary Art

Contemporary Chinese art (中國當代藝術, Zhongguo Dangdai Yishu) often referred to as Chinese avant-garde art, continued to develop since the 1980s as an outgrowth of modern art developments post-Cultural Revolution.

Contemporary Chinese art fully incorporates painting, film, video, photography, and performance. Until recently, art exhibitions deemed controversial have been routinely shut down by police, and performance artists in particular faced the threat of arrest in the early 1990s. More recently there has been greater tolerance by the Chinese government, though many internationally acclaimed artists are still restricted from media exposure at home or have exhibitions ordered closed. Leading contemporary visual artists include Ai Weiwei, Cai Guoqiang, Chan Shengyao, Fang Lijun, Fu Wenjun, He Xiangyu, Huang Yan, Huang Yong Ping, Han Yajuan, Kong Bai Ji, Li Hongbo, Li Hui, Liu Bolin, Lu Shengzhong, Ma Liuming, Qiu Shihua, Shen Shaomin, Shi Jinsong, Song Dong, Li Wei, Christine Wang, Wang Guangyi, Wenda Gu, Xu Bing, Yang Zhichao, Zhan Wang, Zheng Lianjie, Zhang Dali, Zhang Xiaogang, Zhang Huan, Zhou Chunya, Zhu Yu, Ma Kelu, Ding Fang, Shang Yang and Guo Jian.

Visual art

Beginning in the late 1980s there was unprecedented exposure for younger Chinese visual artists in the west to some degree through the agency of curators based outside the country such as Hou Hanru. Local curators within the country such as Gao Minglu and critics such as Li Xianting (栗憲庭) reinforced this promotion of particular brands of painting that had recently emerged, while also spreading the idea of art as a strong social force within Chinese culture. There was some controversy as critics identified these imprecise representations of contemporary Chinese art as having been constructed out of personal preferences, a kind of programmatized artist-curator relationship that only further alienated the majority of the avant-garde from Chinese officialdom and western art market patronage.

Art market

Today, the market for Chinese art, both antique and contemporary, is widely reported to be among the hottest and fastest-growing in the world, attracting buyers all over the world.[22][23][24] The Voice of America reported in 2006 that modern Chinese art is raking in record prices both internationally and in domestic markets, some experts even fearing the market might be overheating.[25] The Economist reported that Chinese art has become the latest darling in the world market according to the record sales from Sotheby's and Christie's, the biggest fine-art auction houses.[26] The International Herald Tribune reported that Chinese porcelains were fought over in the art market as "if there was no tomorrow".[27] Contemporary Chinese art also saw record sales throughout the 2000s. In 2007, it was estimated that 5 of the world's 10 best selling living artists at art auction were from China, with artists such as Zhang Xiaogang whose works were sold for a total of $56.8 million at auction in 2007.[28] In terms of buying-market, China overtook France in the late 2000s as the world's third-largest art market, after the United States and the United Kingdom, due to the growing middle-class in the country.[29][30] Sotheby's noted that contemporary Chinese art has rapidly changed the contemporary Asian art world into one of the most dynamic sectors on the international art market.[31] During the global economic crisis, the contemporary Asian art market and the contemporary Chinese art market experienced a slow down in late 2008.[32][33] The market for Contemporary Chinese and Asian art saw a major revival in late 2009 with record level sales at Christie's.[34] For centuries largely made-up of European and American buyers, the international buying market for Chinese art has also begun to be dominated by Chinese dealers and collectors in recent years.[35] It was reported in 2011, China has become the world's second biggest market for art and antiques, accounting for 23 percent of the world's total art market, behind the United States (which accounts for 34 percent of the world's art market).[36] Another transformation driving the growth of the Chinese art market is the rise of a clientele no longer mostly European or American. New fortunes from countries once thought of as poor often prefer non-Western art; a large gallerist in the field has offices in both New York and Beijing, but clients mainly hailing from Latin America, Asia and the Middle East.[37]

One of the areas that has revived art concentration and also commercialized the industry is the 798 Art District in Dashanzi of Beijing. The artist Zhang Xiaogang sold a 1993 painting for US$2.3 million in 2006, which included blank faced Chinese families from the Cultural Revolution era,[38] while Yue Minjun's work Execution in 2007 was sold for a then record of nearly $6 million at Sotheby's.[39] Collectors including Stanley Ho, the owner of the Macau Casinos, investment manager Christopher Tsai, and casino developer Stephen Wynn, would capitalize on the art trends. Items such as Ming Dynasty vases and assorted Imperial pieces were auctioned off.

Other art works were sold in places such as Christie's including a Chinese porcelain piece with the mark of the Qianlong Emperor sold for HKD $ $151.3 million. A 1964 painting "All the Mountains Blanketed in Red" was sold for HKD $35 million. Auctions were also held at Sotheby's where Xu Beihong's 1939 masterpiece "Put Down Your Whip" sold for HKD $72 million.[40] The industry is not limited to fine arts, as many other types of contemporary pieces were also sold. In 2000, a number of Chinese artists were included in Documenta and the Venice Biennale of 2003. China now has its own major contemporary art showcase with the Venice Biennale. Fuck Off was a notorious art exhibition which ran alongside the Shanghai Biennial Festival in 2000 and was curated by independent curator Feng Boyi and contemporary artist Ai Weiwei.

Museums

- National Art Museum of China (Beijing)

- Palace Museum (Forbidden City, Beijing)

- China Art Museum (Shanghai)

- Power Station of Art (Shanghai)

- National Palace Museum (Taipei, Taiwan)

See also

Notes

- ^ "Early Autumn (29.1)". Detroit Institute of Arts. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- ^ The Chinese character "mo" means ink and "shui" means water

- ^ Sickman, 222

- ^ Rawson, 114-119; Sickman, Chapter 15

- ^ Rawson, Chapter 1, 135–136

- ^ Rawson, 138-138

- ^ Rawson, 135–145; 145–163

- ^ Rawson, 163–165

- ^ a b Rawson, Chapters 4 and 6

- ^ Rawson, 135

- ^ Rawson, 50-54

- ^ a b Mazurkewich, Karen; Ong, A. Chester (2006). Chinese Furniture: A Guide to Collecting Antiques. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-0-8048-3573-2.

- ^ Needham, Joseph; Tsien, Tsuen-hsuin (1985). Paper and printing, Volume 5. Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-521-08690-5.

- ^ a b c Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Plate CCCXII

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (July 3, 2007). "'China's Mona Lisa' Makes a Rare Appearance in Hong Kong". The New York Times. China;Hong Kong;Great Britain. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ a b Capon and Pang, pg. 12

- ^ Capon and Pang, pg. 42

- ^ Capon and Pang, pg. 120

- ^ Capon and Pang, pg. 90, 91

- ^ Capon and Pang, pg. 90

- ^ Capon and Pang, pg. 91

- ^ Vogel, Carol (October 20, 2005). "Christie's Going, Going to China to Hold Auctions. ''The New York Times''". The New York Times. China. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Barboza, David (January 4, 2007). "Booming Chinese Art Market – Report. ''The New York Times''". The New York Times. China. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (December 24, 2006). "Chinese Art – Report. ''The New York Times''". The New York Times. China. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Market Red Hot for Modern Chinese Art. Voice of America.[dead link]

- ^ "''The over-heating art market''. The Economist". The Economist. January 11, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Melikian, Souren (July 30, 2005). "Disregarded yesterday; pricey Chinese art today. ''International Herald Tribune''". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Barboza, David (May 7, 2008). "Some Contemporary Chinese Artists Are Angry About an April Auction at Sotheby's – New York Times". The New York Times. China. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Culture and art Beijing style. Emirates Business-24". Business24-7.ae. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ China way ahead of India in contemporary art. The Economic Times

- ^ Sotheby's – Specialist Department Overview

- ^ Pomfret, James (October 8, 2008). "Chinese art sales weak in Sotheby's HK auction. Reuters". Reuters. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Barboza, David (March 10, 2009). "China's Art Market: Cold or Maybe Hibernating? ''New York Times''". The New York Times. China. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Santini, Laura (December 4, 2009). ""Christie's Sees Hong Kong Revival As Auction Pulls In $212.5 Million". ''The Wall Street Journal''". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Chinese Bidders Conquer Market" article by Souren Melikian in The New York Times April 2, 2010

- ^ AFP (March 18, 2011). "China overtakes Britain as second biggest art market". The Independent. UK. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Genis, Daniel. "Eli Klein on Riding the Wave of China's Contemporary Art Scene". www.Newsweek.com. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ Msnbc. "Msnbc." China's Art scene. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- ^ Chinese painting sets sales record at London auction. thestaronline.com. Retrieved 2011-11-11.

- ^ Bloomberg."Bloomberg." Stanley Ho Buys Chinese Emperor's Throne for HK$13.7 Million. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

References

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

- Edmund Capon and Mae Anna Pang, Chinese Paintings of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Catalogue, 1981, International Cultural Corporation of Australia Ltd.

- Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, 2007 (2nd edn), British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714124469

- Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman L & Soper A, "The Art and Architecture of China", Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1971, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), LOC 70-125675

- MSN Encarta (Archived 2009-10-31)

- The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia

- SHiNE Art Space Gallery

Further reading

- Barnhart, Richard M., et al. Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art: 2002. ISBN 0-300-09447-7.

- Chi, Lillian, et al. A Dictionary of Chinese Ceramics. Sun Tree Publishing: 2003. ISBN 981-04-6023-6.

- Clunas, Craig. Art in China. Oxford University Press: 1997. ISBN 0-19-284207-2.

- Fong, Wen (1973). Sung and Yuan paintings. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870990845.

- Gesterkamp, Lennert. THE HEAVENLY COURT A Study on the Iconopraxis of Daoist Temple Painting

- Gowers, David, et al. Chinese Jade from the Neolithic to the Qing. Art Media Resources: 2002. ISBN 1-58886-033-7.

- Ebrey, Patricia, et al. Taoism and the Arts of China. University of California Press: 2000. ISBN 0-520-22784-0.

- Harper, Prudence Oliver. China: Dawn Of A Golden Age (200–750 AD). Yale University Press: 2004. ISBN 0-300-10487-1.

- Leidy, Denise Patry & Strahan, Donna (2010). Wisdom embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588393999.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mascarelli, Gloria, and Robert Mascarelli. The Ceramics of China: 5000 BC to 1900 AD. Schiffer Publishing: 2003. ISBN 0-7643-1843-8.

- Sturman, Peter Charles. Mi Fu: Style and the Art of Calligraphy in Northern Song China. Yale University Press: 2004. ISBN 0-300-10487-1.

- Sullivan, Michael. The Arts of China. Fourth edition. University of California Press: 2000. ISBN 0-520-21877-9.

- Tregear, Mary. Chinese Art. Thames & Hudson: 1997. ISBN 0-500-20299-0.

- Valenstein, S. (1998). A handbook of Chinese ceramics, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. ISBN 9780870995149 .

- Watt, James C.Y.; et al. (2004). China: dawn of a golden age, 200-750 AD. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 1588391264.

- Watson, William. The Arts of China to AD 900. Yale University Press: 1995. ISBN 0-300-05989-2.

- S. Diglio, Urban Development and Historic Heritage Protection in Shanghai, in Fabio Maniscalco ed., "Web Journal on Cultural Patrimony", 1, 2006

External links

- Chinese Calligraphy - Dao of Calligraphy in English & Mandarin Chinese

- The Final Frontier - Chinese contemporary art at LUX Mag

- Chinese art, calligraphy, painting, ceramics, carving at China Online Museum

- Art History of Chinese calligraphy, painting, and seal making

- China the Beautiful – Chinese Art and Literature Introductions & art classics texts

- Gallery of China – Traditional Chinese Art Essay on Chinese art from neolithic to communist times

- Fine Chinese Art And Chinese Painting The Chinese Ancient Paintings