Directive (EU) 2021/555

| Directive (EU) 2021/555 | |

|---|---|

| |

| European Parliament and Council of the European Union | |

| |

| Citation | Directive (EU) 2021/555 |

| Enacted by | European Parliament and Council of the European Union |

| Enacted | 24 March 2021 |

| Commenced | 26 April 2021 |

| White paper | Completing the internal market |

| Repeals | |

| Directive 91/477/EEC | |

| Status: In force | |

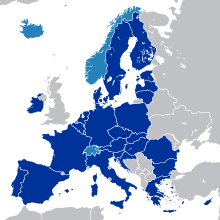

Directive (EU) 2021/555 is a legal act of the European Union which sets minimum standards regarding civilian firearms acquisition and possession that EU member states must implement into their national legal systems. It codified Council Directive 91/477/EEC of 18 June 1991.

The member states are free to adopt more stringent rules, which leads to differences in the extent of citizens' legal access to firearms within different EU countries.

Directive No. 91/477/EC[edit]

The 1985 white paper on completion of the internal market (by the European Commission) stressed that the absence of border checks must not provide an incentive to buy arms in countries with less strict legislation. This goal was to be reached by approximation of the countries' national legislation on firearms.[1]

Prior to abolition of the internal border controls under the Schengen Agreement, the Council of the European Communities adopted the Directive 91/477/EEC, which was later, in 2008, amended by Directive 2008/51/EC. As a directive, it is not a self-executing norm, but a legislative act which requires each member state to achieve a particular result without dictating the means of achieving it. Member states must meet the minimum requirements laid down by the directive, but may also elect to adopt more stringent rules.[2] Certain countries such as Ireland are thus unaffected as they have maintained more stringent gun control laws than those effectively set as a minimum by the European Union, while others, like the Czech Republic, were forced to introduce more regulation in their national legislation.

The original Directive No. 91/477/EC was adopted in 1991 on the background of abolition of intra-Community frontiers. It aimed at partial approximation of national legislation that would prevent passing possession of firearms from one member state to another, unless it is done according to rules established by the directive. At the same time, the directive introduced the European Firearms Pass that would allow hunters and target shooters to move between the member states without unnecessary impediments.[3] Generally, a person with a valid European Firearms Pass travelling to or through other member states may be in possession of one or more firearms during that journey, provided that they are in possession of a European Firearms Pass listing such firearm or firearms and provided that they are able to substantiate the reasons for their journey, in particular by producing an invitation. That, however, does not apply to a journey through member states that have more stringent laws and generally prohibit such firearms within their territory.[4]

The directive was without prejudice to any national provisions concerning carrying of weapons, hunting or target shooting[5] and allowed member states to adopt more stringent rules.[6] The directive introduced A-B-C-D categories of firearms (see below) with different rules pertaining to their acquisition.[7] Under the directive, national laws were to allow acquisition of A and B category firearms only subject to authorisation,[8] while C category firearms were subject to registration.[9]

Handing over of a firearm to a person from a different country was to be allowed only subject to a written declaration of authorisation of such a transfer by the country of residence of the acquiree.[10]

The directive also bound member states to intensify controls on external community frontiers in order to prevent supply of black market firearms into the community.[11]

Amending Directive No. 2008/51/EC[edit]

Following the signing of the United Nations Protocol on the illicit manufacturing of and trafficking in firearms, their parts, components and ammunition, annexed to the Convention against transnational organised crime, the European Council and Parliament noted the need to amend the existing firearms directive in order to bring European legislation in line with the UN Protocol rules.[12]

Further reasons for amendment included increase in the use of converted weapons within the Community, bringing distance (internet) purchases of firearms within the scope of authority of the Directive and better tracing of firearms.[13]

The directive required Member States to enact legislation that would require marking and registration of any firearm or essential part placed on the market and to establish national computerised data-filing system concerning registration.[14]

The Directive also placed a set of specific duties on the European Commission:

- to submit a report to the EP and EC on the application of the directive by July 2015[15]

- to submit a report to the EP and EC on possible simplification of categorisation of firearms into two categories with a view to the better functioning of internal markets by July 2012[16]

- to submit a report to the EP and EC on issue on desirability of placing of replica firearms within the scope of authority of the Directive[17]

- to issue common guidelines on deactivation standards and techniques to ensure that deactivated firearms are rendered irreversibly inoperable in line with procedure in Article 13a(2)[18]

Firearm categorisation prior to 13 June 2017

| Firearm category | Designation | Minimum standard required |

|---|---|---|

| Category A – Prohibited firearms |

1. Explosive military missiles and launchers. 2. Automatic firearms. 3. Firearms disguised as other objects. 4. Ammunition with penetrating, explosive or incendiary projectiles, and the projectiles for such ammunition. 5. Pistol and revolver ammunition with expanding projectiles and the projectiles for such ammunition, except in the case of weapons for hunting or for target shooting, for persons entitled to use them. |

In general, the firearms are prohibited, authorisation to acquire and possession may be possible only in special cases.[19] |

| Category B – Firearms subject to authorisation |

1. Semi-automatic or repeating short firearms. 2. Single-shot short firearms with centre-fire percussion. 3. Single-shot short firearms with rimfire percussion whose overall length is less than 28 cm. 4. Semi-automatic long firearms whose magazine and chamber can together hold more than three rounds. 5. Semi-automatic long firearms whose magazine and chamber cannot together hold more than three rounds, where the loading device is removable or where it is not certain that the weapon cannot be converted, with ordinary tools, into a weapon whose magazine and chamber can together hold more than three rounds. 6. Repeating and semi-automatic long firearms with smooth-bore barrels not exceeding 60 cm in length. 7. Semi-automatic firearms for civilian use which resemble weapons with automatic mechanisms. |

Acquisition and possession allowed only |

| Category C – Firearms subject to declaration |

1. Repeating long firearms other than those listed in category B, point 6. 2. Long firearms with single-shot rifled barrels. 3. Semi-automatic long firearms other than those in category B, points 4 to 7. 4. Single-shot short firearms with rimfire percussion whose overall length is not less than 28 cm. |

Acquisition and possession allowed only |

| Category D – Other firearms |

Single-shot long firearms with smooth-bore barrels. | Acquisition and possession allowed only to persons older than 18.[20] |

Amending Directive (EU) 2017/853[edit]

Legislative procedure[edit]

2015 European Commission Amendment Proposal[edit]

The European Commission proposed a package of measures aimed to "make it more difficult to acquire firearms in the European Union" on 18 November 2015,[23] which became known as the "EU Gun Ban".[24][25][26][27] President Juncker introduced the aim of amending Directive 91/477/EEC as a Commission's reaction to a previous wave of Islamist terror attacks in several EU cities. The main aim of the Commission proposal rested in banning B7 firearms (and objects that look alike).

Opponents point out that no such firearm has previously been used during commitment of a terror attack in EU. Of 31 terror attacks committed in the EU in the years preceding the Commissions proposal, 9 were committed with guns, the other 22 with explosives or other means (truck in Nice). Of these 9, 8 cases made use of either illegally smuggled or illegally refurbished deactivated firearms (for which the European Commission didn't enact any rules, despite being tasked to do so in the Directive No. 2008/51/EC, see above) while during the 2015 Copenhagen shootings a military rifle stolen from the army, was used.[28]

The European Commission didn't present an impact assessment for the proposed amendment Directive. One was prepared by the Czech Ministry of Interior, according to which the main impacts of the proposed Directive amendment, if accepted, would be:[29]

- Risks to internal security due to possible transfer of legal firearms into illegality and potentially black market, into hands of criminals and terrorists, as many owners would refuse to surrender their firearms.

- Risk to defensive capabilities due to crippling of firearms manufacturing and possible move of small arms factories abroad.

- Threat to national culture due to destroying of private collectors and museums owned firearms.

- Rise of unemployment connected with crippling of legal firearms manufacturing and trade.

- Impact on hunting due to restrictions of semi-automatic rifles, leading to rise in animal-car accidents and connected damages, injuries and deaths.

- Impact on state budget due to combination of having to pay up to tens of billions Czech crowns (billions of Euros) as compensation for banned firearms and rise in unemployment

The European Commission proposal, if adopted, would have the following effect:[30][29]

- bringing alarm, signal, salute, acoustic, replica and deactivated firearms within the scope of authority of the Directive, thus requiring that their owner possesses respective licences

- standard medical testing as a prerequisite to firearm licence acquisition

- absolute prohibition of possession of A category firearms (even if having been deactivated) and destroying them, which would have particular effect on[29]

- private collectors and museums; bodies concerned with the cultural and historical aspects of weapons and recognised as such by the Member State in whose territory they are established may be authorised to keep in their possession firearms classified in category A acquired before the date of entry into force of the Directive provided they have been deactivated,[31] i.e. rendered permanently unfit for use, ensuring that all essential parts of the firearm have been rendered permanently inoperable and incapable of removal, replacement or a modification that would permit the firearm to be reactivated in any way[32] which, from historical perspective, is on par with destruction.[33]

- manufacturing of firearms for security forces within the EU (private companies could not possess A category firearms that they manufacture before selling them to police or military)

- private owners, especially as regards of B category firearms that would be newly categorised as A firearms (automatic firearms which have been converted into semi-automatic and semi-automatic firearms which "resemble weapons with automatic mechanism")

- five-year maximum licence length (may be renewed)

In the proposal, the European Commission suggested that the Amendment includes Article 10b, which would bind the Commission to issue common deactivation standards[34] as it was ordered to do in the 2008 Directive (see above)[35] and which the Commission issued on 19 December 2015.[32] Meanwhile, poorly deactivated firearms, alongside smuggling from third countries, became one of major sources of black market guns used by criminals and terrorists in Europe, having been used in 2015 Hypercacher kosher supermarket siege, France.[36]

2016 Dutch Presidency reworked amendment proposal[edit]

The Dutch EU Presidency introduced 2nd reworked version of the amendment proposal on 4 April 2016. Apart from taking over all of Commission's proposals, Netherlands went further with proposing, among other things, a total ban on all semi-automatic firearms capable of being fitted with a magazine with more than six rounds, i.e. all pistols and most existing semi-automatic rifles.[29]

Three weeks later, the Dutch presidency introduced a third version of the amendment proposal. This time Netherlands proposed, on top of EU Commission proposal, to ban self-loading firearms that have a magazine with more than 20 rounds attached, as well as ban such magazines themselves. According to Czech Ministry of Interior Impact Assessment, it would make a total chaos in firearms categorisation (i.e. a firearm would be B category when a 15-round magazine is inserted, and A category a second later after inserting a different, larger magazine) as well as vagueness, as it allowed also interpretation that all firearms that might potentially accept a larger than 20 rounds magazines might be themselves banned. The Impact Assessment further pointed out that millions of now legally owned standard capacity magazines could be expected to flow into the black market. Moreover, such firearms could only be owned for hunting and sporting purposes, having crippling effect in countries where self defence is prevailing reason for firearm possession, such as the Czech Republic. To appeal to some disagreeing countries (Finland, Lithuania, Estonia, Switzerland), the proposal now included special exemptions for firearms possessions by military reserve or militia members.[29]

The Dutch Presidency proposed to remove the entire D category of firearms and move the firearms into C category, i.e. making for example muzzle loaders subject to same rules as firearms.[37]

LIBE and IMCO EP Committees amendment proposals[edit]

The amendment proposal was introduced at the European Parliaments' Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) and Committee on Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO). Its members slammed the proposal as "unworkable". According to IMCO chair Vicky Ford, the Commission proposal "was poorly worded and we need to make sure that the legislation is practicable."[38]

This led to filing of over 900 proposals for changes to the Commission amendment proposal.[38]

Trilogue final proposal[edit]

Instead of going through the standard process of up to three rounds of debate and amendment between the Council and the Parliament, the amendment proposal entered the Trilogue.

COREPER[edit]

The European Council's position on the issue was negotiated through Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER). In a leaked "non-paper" that was sent to other countries' representations shortly before the 30 November 2016 meeting, the Permanent Representation of France to the EU pointed out that France, (Germany), Italy and Spain consider the following as particularly essential goals:[40][41][42]

- total ban on semiautomatic firearms that were converted from automatic ones and subjecting "salute and acousting weapons" to the Directive regime,

- definition of precise derogations from prohibitions that would avoid invocation of internal security derogation,

- implementation of Europe-wide system for exchange of information,

- ensuring close control of sales of firearms, especially by means of distance communication, and

- exclusion of technical standards for deactivation from the scope of the directive.

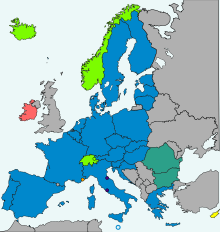

On 20 December 2016, the COREPER, which included a representative of Switzerland (the rules extend to the country due to its membership of Schengen Area) reached a majority decision in favour of the proposed amendment. Only two countries opposed: Luxembourg, which would prefer more firearm restrictions, and the Czech Republic.[43]

The Czech Republic further lodged a declaration of reservations which was published by the Czech Ministry of Interior. According to the declaration key elements of the proposal are inappropriate in substance and legally unclear and sometimes disproportionate. It further included regrets over unclear, unnecessary, overbroad and injudicious prohibitions of some semi-automatic firearms which may "cause transfer of significant portion of firearms that are held legally now into illegal ownership or even black market and thus increase their availability to terrorists and criminals". The Czech Republic also stated concern about last minute changes to the proposal about which the Member States were not informed in advance and thus could not properly evaluate their impact.[44]

The COREPER version was closer to the second Dutch proposal (third reworked version) than to original Commission version.[43]

IMCO[edit]

On 26 January 2017, IMCO Committee accepted the COREPER amendment proposal by majority of 25 to 9 votes. Among those that did not support the proposal were all four Czech committee members.[45] According to Vicky Ford, the IMCO negotiators amended the proposal to defend the interests of legal owners and close some loopholes, especially on poorly deactivated firearms. Ford commented that she would prefer a version that would not include magazine limitations, however she accepted it as it was of extreme importance to some countries.[46]

Shadow rapporteur Dita Charanzová said that she has never in her career met a proposal that was politicised this much, with the Commission exercising extreme pressure especially by the end of the negotiations. Charanzová said that, since first proposing the amendment in 2015, the Commission had not presented an Impact Assessment, although it is required by its own legislative rules and although she had asked for it numerous times. She further asked the Commission what it had done with over 28,000 inputs gained during public consultation phase, but to no avail. Further, representatives of the Commission would often bring last minute changes to meetings they couldn't justify – at one point trying to answer her objection "with a definition taken from Wikipedia". Charanzová also noted the rise of anti-EU sentiment connected with the proposal.[47]

Mylène Troszczynski filed a minority opinion on behalf of the ENF, according to which the legislation "seeks only to restrict the civil liberties of blameless citizens in their efforts to acquire and possess firearms".[48]

European Parliament Vote[edit]

The European Parliament voted on the proposal during its session on 14 March 2017.

There were altogether 164 proposals for amendments filed by MEPs that sought to change the text negotiated in the Trialogue.[48] However, under the Rules of Procedure of the European Parliament Art. 53(3), any provisional agreement reached in the Trialogue under Art 69f(4) "shall be given priority in voting and shall be put to a single vote".[49] MEP Dita Charanzová put forward a motion on behalf of the ALDE Group that would allow voting on the MEPs' proposals for changes, arguing that the plenary "has never had the opportunity to take the position on this important text as it was negotiated directly by the Committee, therefore I ask all my colleagues to vote in favor of this request which would simply allow all members to express their opinions". Vicky Ford then argued that these amendments had been debated in the Committee, discussed with the Council and ultimately rejected by the Member States. She argued that adopting the amendments would "destabilize the entire agreement", throwing away "all the hard work" and "success that the Parliament has had in improving the text". Charanzová's proposal was rejected by unknown margin, as, according to chair "the vote was absolutely clear for everyone to see, there is no point in having a check" with no record of number of votes cast being made.[50][51]

The Parliament passed the proposal by 491 to 178 margin after 4 minutes and 50 seconds with no public debate.[50]

| EU Parliament vote on the European Firearms Directive Amendment – Trialogue version (14 March 2017)[52] |

Number of votes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Yay | Nay | Abstained | |

| Vote to reject the proposal | 699 | 123 | 562 | 014 |

| Vote to allow voting on amendments | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| Vote to adopt the proposal | 697 | 491 | 178 | 028 |

European Council vote[edit]

European Council approved the proposal by majority vote on 25 April 2017. The Czech Republic, Luxembourg and Poland voted against the proposal.

Publishing[edit]

The Directive was published under No. (EU) 2017/853 on 17 May 2017 in the Official Journal. Member States will have 15 months to implement the Directive into their national legal systems.

Content[edit]

Newly prohibited firearms[edit]

|

Under the 2017 Directive, certain firearms formerly classified as B category (subject to authorization) firearms are newly reclassified as A category (prohibited) firearms and thus they are banned for certain classes of civilians. These are:

|

The Directive, however, includes several exemptions that Member States may enact and under which the above mention banned firearms may either remain in possession of existing owners or may be acquired by new owners:

|

Deactivated firearms[edit]

European Commission has been tasked to enact rules for proper deactivation of firearms under the Directive No. 2008/51/EC of 21 May 2008[67] and did so on 19 December 2015 through Regulation No. (EU) 2015/2403.[32] While the Regulation was adopted to ensure that deactivated firearms may not be refurbished to function again, the 2017 Directive set forth that possession of A and B category firearms deactivated under the Regulation shall be subject to same rules as possession of live C category firearms.[68]

Exchange of information[edit]

Under the 2017 Directive, the Commission is tasked to provide a system for exchange of information between member states on the authorisations granted for the transfer of firearms to another member state and information with regard to refusals to grant authorisations as provided for in Articles 6 and 7 on grounds of security or relating to the reliability of the person concerned.[69]

Monitoring of gun owners, authorisation limitation[edit]

Member states shall have in place a monitoring system to ensure that the conditions of authorisation set by national law are met throughout the duration of the authorisation and, inter alia, relevant medical and psychological information is assessed. In case conditions of authorisation are not met, the State shall withdraw the authorisation.[70]

Authorization for possession of firearms be shall be reviewed periodically in intervals not exceeding 5 years and renewed or prolonged if conditions of its granting are still met.[71]

Directive review[edit]

The Commission shall by 14 September 2020 and then periodically every 5 years submit a report on the Directive and propose further changes.[72]

Firearms categorisation[edit]

Firearms categorisation underwent a general overhaul.

| Firearm category | Designation | Minimum standard required |

|---|---|---|

| Category A – Prohibited firearms |

1. Explosive military missiles and launchers. 2. Automatic firearms. 3. Firearms disguised as other objects. 4. Ammunition with penetrating, explosive or incendiary projectiles, and the projectiles for such ammunition. 5. Pistol and revolver ammunition with expanding projectiles and the projectiles for such ammunition, except in the case of weapons for hunting or for target shooting, for persons entitled to use them. 6. Automatic firearms which have been converted into semi-automatic firearms, without prejudice to Article 7(4a). 7. Any of the following centre-fire semi-automatic firearms: (a) short firearms which allow the firing of more than 21 rounds without reloading, if: (i) a loading device with a capacity exceeding 20 rounds is part of that firearm; or (ii) a detachable loading device with a capacity exceeding 20 rounds is inserted into it; (b) long firearms which allow the firing of more than 11 rounds without reloading, if: (i) a loading device with a capacity exceeding 10 rounds is part of that firearm; or (ii) a detachable loading device with a capacity exceeding 10 rounds is inserted into it. 8. Semi-automatic long firearms (i.e. firearms that are originally intended to be fired from the shoulder) that can be reduced to a length of less than 60 cm without losing functionality by means of a folding or telescoping stock or by a stock that can be removed without using tools. 9.Any firearm in this category that has been converted to firing blanks, irritants, other active substances or pyrotechnic rounds or into a salute or acoustic weapon. |

In general, the firearms are prohibited, authorisation to acquire and possession may be possible only in special cases.[19] Categories 6 through 9 added in 2017 – special rules to acquisition may apply, see above |

| Category B – Firearms subject to authorisation |

1. Repeating short firearms. 2. Single-shot short firearms with centre-fire percussion. 3. Single-shot short firearms with rimfire percussion whose overall length is less than 28 cm. 4. Semi-automatic long firearms whose loading device and chamber can together hold more than three rounds in the case of rimfire firearms and more than three but fewer than twelve rounds in the case of centre-fire firearms. 5. Semi-automatic short firearms other than those listed under point 7(a) of category A. 6. Semi-automatic long firearms listed under point 7(b) of category A whose loading device and chamber cannot together hold more than three rounds, where the loading device is detachable or where it is not certain that the weapon cannot be converted, with ordinary tools, into a weapon whose loading device and chamber can together hold more than three rounds. 7. Repeating and semi-automatic long firearms with smooth-bore barrels not exceeding 60 cm in length. 8. Any firearm in this category that has been converted to firing blanks, irritants, other active substances or pyrotechnic rounds or into a salute or acoustic weapon. 9. Semi-automatic firearms for civilian use which resemble weapons with automatic mechanisms other than those listed under point 6, 7 or 8 of category A.’; |

Acquisition and possession allowed only by persons who have good cause and

|

| Category C – Firearms subject to declaration |

1. Repeating long firearms other than those listed in point 7 of category B. 2. Long firearms with single-shot rifled barrels. 3. Semi-automatic long firearms other than those listed in category A or B. 4. Single-shot short firearms with rimfire percussion whose overall length is not less than 28 cm. 5. Any firearm in this category that has been converted to firing blanks, irritants, other active substances or pyrotechnic rounds or into a salute or acoustic weapon. 6. Firearms classified in category A or B or this category that have been deactivated in accordance with Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/2403. 7. Single-shot long firearms with smooth-bore barrels placed on the market on or after 14 September 2018.’ |

Acquisition and possession allowed only by persons who have good cause and

|

After Effects[edit]

European Court of Justice challenge[edit]

A sticker promoting petition against the Directive on a lamp post at the National Monument in Vitkov, Prague, Czech Republic.

The Czech Government announced that the country will challenge the proposed amendment Directive before the European Court of Justice[73] by 17 August 2017 at the latest due to its impact on legal owners of historical replicas, semi-automatic firearms and standard capacity magazines. According to the Ministry of Interior, the Directive will affect law-abiding owners of hundreds of thousands firearms and well over a million firearm magazines.[74]

The Minister of Interior, Milan Chovanec commented: "Filing the suit gives me no pleasure, but there is no other option left. The Directive violates the principle of proportionality as well as prohibition of discrimination. We shall not allow the EU to use the guise of fight against terrorism in order to disproportionately infringe onto the Member States' scope of authority and citizens' rights. The EU Gun Ban would affect almost all of the 300,000 legal gun owners in the country. This is why we will lodge not only the suit to invalidate the Directive, but also propose postponement of Directive's effectiveness."[74] The suit against the 2017 Amending Directive was filed on 9 August 2017.[75] In the meantime both Hungary and Poland joined the proceedings. The Czech Republic bases the suit on the following reasoning:[76]

- EU legislatory over-reach: The Directive was adopted based on the Art. 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union which authorises the EU to adopt acts aimed at approximation of national laws for the purpose of the establishment and functioning of the internal market. Even though based on the TFEU Art. 114, the Directive aims solely at prevention of crime and terrorism. However, the EU lacks legal basis for adopting harmonisation acts in this field – Article 84 of TFEU explicitly prevents the EU from harmonising Member State laws in this area.

- The Directive is disproportionate: EU failed to consider proportionality of the adopted Directive and intentionally didn't obtain sufficient information on the issue. The failure to obtain sufficient information led to adoption of measures which are not only clearly disproportionate to its aim, but also completely unable to achieve them. The rate of crimes involving use of legal firearms in EU is marginal. The only end the Directive may achieve is curbing rights of law-abiding citizens which has no effect on terrorism. EU should focus on effective fight against illegal firearms, co-operation of police authorities and better exchange of information between Member States.

- The Directive is in breach of principle of legal certainty: A number of Directive's Articles are vague and ambiguous, making it unclear as regards what rights and obligations are set by them. This applies especially to magazine restriction limits and PDW limitations.

- Article 6(6) of the Directive is discriminatory: Specifically, a part of Article 6(6) of the Directive provides a special exemption that may be applied only by Switzerland which makes it discriminatory and should thus be nullified.

Czech Constitutional Amendment Proposal[edit]

On 15 December 2016, Czech Ministry of Interior introduced a proposal to amend Constitutional Act No. 110/1998 Col., on Security of the Czech Republic expressly providing the right to be armed as part of citizen's duty of participation in provision of internal order, security and democratic order. The proposal aimed at making use of EU Primary Law internal security derogation .[77] Its purpose lays at utilisation of already existing specific conditions as regards firearms ownership in the Czech Republic (240.000 people having concealed carry licence, high level of ownership of semi-automatic firearms suitable for self-defense as compared to other EU countries) for security purposes, whereby firearms owners should contribute to soft targets protection.[77]

On 6 February 2017, the proposal was lodged by 36 members of parliament into legislative process. It must gain support of 3/5 of all Members of Chamber of Deputies and 3/5 of Senators present to be passed. This proposal was approved by the Chamber of Deputies on 28 June 2017 with a solid majority of 139:9 [78]

On 6 December 2017, the proposal was rejected by the Senate. Since the Chamber of Deputies cannot overturn Senate rejection of proposed changes of constitution, this means the end of the proposal.[79]

Possible Swiss referendum[edit]

According to Swiss People's Party vice-president Christoph Blocher, Switzerland should consider abandoning EU's borderless Schengen Area if the Swiss people reject the proposed measures in a referendum.[80]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ European Commission (14 June 1985), Completing the Internal Market. White Paper from the Commission to the European Council (PDF), Brussels, p. 17

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Directive (EU) 2021/555, Art. 3

- ^ Council of European Communities (18 June 1991), COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 18 June 1991 on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (91/477/EEC), Luxembourg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), recital. - ^ Directive (EU) 2021/555, Art. 17.

- ^ Council of European Communities (18 June 1991), COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 18 June 1991 on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (91/477/EEC), Luxembourg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), Article 2. - ^ Council of European Communities (18 June 1991), COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 18 June 1991 on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (91/477/EEC), Luxembourg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), Article 3. - ^ Council of European Communities (18 June 1991), COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 18 June 1991 on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (91/477/EEC), Luxembourg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), Article 1(1). - ^ Council of European Communities (18 June 1991), COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 18 June 1991 on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (91/477/EEC), Luxembourg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), Article 6, 7. - ^ Council of European Communities (18 June 1991), COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 18 June 1991 on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (91/477/EEC), Luxembourg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), Article 8. - ^ Council of European Communities (18 June 1991), COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 18 June 1991 on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (91/477/EEC), Luxembourg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), Article 9. - ^ Council of European Communities (18 June 1991), COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 18 June 1991 on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (91/477/EEC), Luxembourg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), Article 15(1) - ^ European Parliament and the Council (21 May 2008), DIRECTIVE 2008/51/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 May 2008 amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons, recital.

- ^ European Parliament and the Council (21 May 2008), DIRECTIVE 2008/51/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 May 2008 amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons, recital.

- ^ European Parliament and the Council (21 May 2008), DIRECTIVE 2008/51/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 May 2008 amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons, Article 4.

- ^ European Parliament and the Council (21 May 2008), DIRECTIVE 2008/51/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 May 2008 amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons, Article 17.

- ^ European Parliament and the Council (21 May 2008), DIRECTIVE 2008/51/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 May 2008 amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons, Article 17.

- ^ European Parliament and the Council (21 May 2008), DIRECTIVE 2008/51/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 May 2008 amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons, Article 17.

- ^ European Parliament and the Council (21 May 2008), DIRECTIVE 2008/51/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 May 2008 amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons, Annex 1.

- ^ a b European Firearms Directive, Art. 6

- ^ a b c d e f g h European Firearms Directive, Art. 5

- ^ a b Directive (EU) 2021/555, Art. 10

- ^ Directive (EU) 2021/555, Art. 11

- ^ "European Commission strengthens control of firearms across the EU". European Commission. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Finland seeks exception from EU gun ban". Reuters. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "EU Gun Ban : Intervention Suisse à Bruxelles". ASEAA. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "Trilog schließt die Verhandlungen zum "EU-Gun ban"". Firearms United. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "Gun lobby stirs to life in Europe". Politico. 5 April 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "Le B7? Mai usate!". armietiro.it. 27 November 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Analýza možných dopadů revize směrnice 91/477/EHS o kontrole nabývání a držení střelných zbraní". Czech Ministry of Interior. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ European Commission (18 November 2015), Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (PDF)

- ^ a b European Commission (18 November 2015), Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (PDF) article 6

- ^ a b c European Commission (19 December 2015), COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2015/2403 of 15 December 2015 establishing common guidelines on deactivation standards and techniques for ensuring that deactivated firearms are rendered irreversibly inoperable Recital, paragraph 2

- ^ "Právo: EU's planned arms directive is nightmare for Czech museums". Prague Daily Monitor. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ European Commission (18 November 2015), Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (PDF)

- ^ European Parliament and the Council (21 May 2008), DIRECTIVE 2008/51/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 May 2008 amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons, Annex 1.

- ^ "Slovakia was a gun shop for terrorists, crooks" (in Czech). Slovak Spectator. 3 August 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Then they came for the muzzleloaders: EU moves to regulate black powder guns due to terrorism". Guns.com. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Parliament slams Commission's 'unworkable' gun law proposals". Parliament Magazine. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Where European democracy goes to die". Politico. 7 December 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Non-paper on the revision of Council directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons". Permanent Representation of France to the EU. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "Odpověď na žádost o informace [Answer to information request under the Freedom of Information Act]". Ministry of Interior of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "Jak to chodí v Bruselu [The way it is done in Brussels]". Ministry of Interior of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ a b "EU states reach difficult compromise on firearms". Euractiv. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Declaration of the Czech Republic on the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons". Government of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Committee on the Internal Market and Consumer Protection: Result of roll-call votes of 26 January 2017" (PDF). IMCO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Control of the acquisition and possession of weapons: extracts from the vote and statement by Vicky Ford (ECR, UK)". European Parliament. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "EU Gun Ban: Dita Charanzová speaks out to Firearms United". Firearms United. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ a b European Parliament (2017), REPORT on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Council Directive 91/477/EEC on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons, Brussels, retrieved 23 April 2017

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ European Parliament (2017), Rules of Procedure of the European Parliament, Brussels, retrieved 23 April 2017

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b European Parliament (2017), Plenary session – sitting of 2017-03-14 (video coverage), Brussels, retrieved 23 April 2017

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ European Parliament (2017), A8-0251/2016 CRE 14/03/2017 – 6.4 Debates Tuesday, 14 March 2017 – Strasbourg 6.4. Control of the acquisition and possession of weapons (A8-0251/2016 – Vicky Ford) (vote), Brussels, retrieved 23 April 2017

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Video coverage – Sitting of 2017-03-14

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 19(b)(ii)(6.)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 19(b)(ii)(7.)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 5(3)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 5(3) a contrario

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 19(b)(ii)(8.)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 19(b)(ii)(9.)

- ^ "Proti regulaci zbraní bojovali milovníci vojenské historie s košťaty v ruce [Reenactors fight against firearms regulation with broomsticks in hands]" (in Czech). novinky.cz. 20 May 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ a b Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 6(6.)

- ^ The Directive does not refer to Swiss Militiamen per se, it refers to: "As regards firearms classified in point 6 of category A, Member States applying a military system based on general conscription and having in place over the last 50 years a system of transfer of military firearms to persons leaving the army after fulfilling their military duties may grant to those persons, in their capacity as a target shooter, an authorisation to keep one firearm used during the mandatory military period. The relevant public authority shall transform those firearms into semi-automatic firearms and shall periodically check that the persons using such firearms do not represent a risk to public security. The provisions set out in points (a), (b) and (c) of the first subparagraph shall apply." There is no other country with similar system existing in the EU.

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 6(3.)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 6(5.)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 6(4.)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 6(2.)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Art. 7(b)(4a.)

- ^ Directive No. 2008/51/EC Annex 1

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Annex 1

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Article 14(4)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Article 5(2)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Article 7(4)

- ^ Directive (EU) 2017/853, Article 17

- ^ "Napadneme evropskou směrnici, která chce lidem vzít zbraně, řekl Chovanec [Chovanec said: We will challenge the European Directive that aims at taking away people's ability to be armed.]". Euractiv. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ a b "ČR podá žalobu proti směrnici EU o zbraních [CR will file suit against the European Firearms Directive]". Ministry of Interior. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ "Czechs take legal action over EU rules on gun control". Reuters. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ "Věcné shrnutí žaloby České Republic proti Evropskému parlamentu a Radě [Summary of Czech Republic suit against the European Parliament and Council of the EU]". Ministry of Interior of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ a b Ministry of Interior (2016), Proposal of amendment of constitutional act no. 110/1998 Col., on Security of the Czech Republic (in Czech), Prague, retrieved 16 December 2016

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ 36 Members of Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic (2017), Proposal of amendment of constitutional act no. 110/1998 Col., on Security of the Czech Republic (in Czech), Prague, retrieved 12 February 2017

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Senát neschválil legálním držitelům zbraní zasahovat k zajištění bezpečnosti státu | Domov". Lidové noviny. 6 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ "Swiss tell EU: Hands off veterans' assault rifles". Reuters. Retrieved 12 March 2017.