Dog communication

Dog communication is the transfer of information between dogs, and also the transfer of information between dogs and humans. Behaviors associated with dog communication include eye gaze, facial expression, vocalization, body posture (including movements of bodies and limbs) and gustatory communication (scents, pheromones and taste). Humans communicate with dogs by using vocalization, hand signals, body posture and touch.

Dog-human communication

Both humans and dogs are characterized by complex social lives with rich communication systems, but it is also possible that dogs, perhaps because of their reliance on humans for food, have evolved specialized skills for recognizing and interpreting human social-communicative signals. Four basic hypotheses have been put forward to account for the findings.

- Dogs, by way of their interactions with humans, learn to be responsive to human social cues through basic conditioning processes.[2]

- By undergoing domestication, dogs not only reduced their fear of humans but also applied all-purpose problem-solving skills to their interactions with people. This largely innate gift for reading human social gestures was inadvertently selected for via domestication.[3][4]

- Dogs' co-evolution with humans equipped them with the cognitive machinery to not only respond to human social cues but to understand human mental states; a so-called theory of mind.[5][6]

- Dogs are adaptively predisposed to learn about human communicative gestures. In essence they come with a built-in "head start" to learn the significance of people's gestures, in much the same way that white-crowned sparrows acquire their species-typical song[7] and ducklings imprint on their own kind.[8]

The pointing gesture is a human-specific signal, is referential in its nature, and is a foundational building block of human communication. Human infants acquire it weeks before the first spoken word.[9] In 2009, a study compared the responses to a range of pointing gestures by dogs and human infants. The study showed little difference in the performance of 2-year-old children and dogs, while 3-year-old children's performance was higher. The results also showed that all subjects were able to generalize from their previous experience to respond to relatively novel pointing gestures. These findings suggest that dogs demonstrate a similar level of performance as 2-year-old children that can be explained as a joint outcome of their evolutionary history as well as their socialization in a human environment.[10]

One study has indicated that dogs are able to tell how big another dog is just by listening to its growl. A specific growl is used by dogs to protect their food. The research also shows that dogs do not, or can not, misrepresent their size, and this is the first time research has shown animals can determine another's size by the sound it makes. The test, using images of many kinds of dogs, showed a small and big dog and played a growl. The result showed that 20 of the 24 test dogs looked at the image of the appropriately sized dog first and looked at it longest.[11]

Depending on the context, a dog's barks can vary in timing, pitch, and amplitude. It is possible that these have different meanings.[12]

Additionally, most people can tell from a bark whether a dog was alone or being approached by a stranger, playing or being aggressive,[13] and able tell from a growl how big the dog is.[14] This is thought to be evidence of human-dog coevolution.[14]

Visual

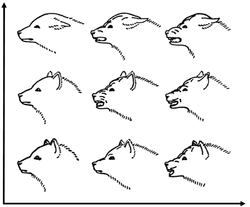

Dogs communicating emotions through body positioning were illustrated in Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals published in 1872.

- Examples of body positioning to communicate different emotions in dogs.

-

"Small dog watching a cat on a table"

-

"Dog approaching another dog with hostile intentions"

-

"Dog in a humble and affectionate frame of mind"

-

"Dog caressing his master"

-

"Half-bred shepherd dog"

-

"Head of snarling dog"

In her book On Talking Terms with Dogs,[15] Turid Rugaas identifies around 30 signals that she calls calming signals. The notion of dominance and submission is much debated.[16][17] In her book, she does not use these terms to differentiate behaviour. She describes calming signals as a way for dogs to calm themselves down or other humans/dogs around them. These are some of the signals she identifies:

- Licking/tongue flicks

- Sniffing the ground

- Turning away/turning of the head

- Play bow

- Walking slowly

- Freezing

- Sitting down

- Walking in a curve

- Yawning

- "Smiling"

- Wagging the tail

- Urinating

- Soft face

- Fiddling

- Lying down

Mouth shape:

Mouth relaxed and slightly open; tongue perhaps slightly visible or draped over the lower teeth – this is the sign of a content and relaxed dog.[1]: 114

Mouth closed, no teeth or tongue visible. Usually associated with the dog looking in one direction, and the ears and head may lean slightly forward – this shows attention, interest, appraising the situation.[1]: 115

Curling or pulling the lips to expose the teeth and perhaps the gums – is a warning signal showing the weapons (teeth), the other party has time to back down, leave or show a pacifying gesture.[1]: 116

Mouth elongated as if pulled back, stretching out the mouth opening and therefore showing the rear teeth – shows a submissive dog yielding to the dominant dog's threat.[1]: 119

"Smiling" is also recognized as a calming signal.[15]

Head position:

A dominant or threatening dog that looks directly at another individual – this is a threat, it is pointing its weapons (muzzle/teeth) at them.[1]: 120

A dominant dog turning its head to one side away from a submissive dog – this is calming them, indicating that it is not going to attack.[1]: 120

A less dominant dog approaches a dominant dog with its head down, and only on occasion quickly pointing its muzzle towards the higher-status dog – shows no fight intended.[1]: 120

In an alternate interpretation that does not involve dominance and submission, turning the head away is recognized as a calming signal.[15]

Yawn: A dog yawn – as with humans, a dog will yawn when tired to help awaken it. Also, a dog will yawn when under stress, or when being menaced by aggression signals from another dog when it can be used as a pacifying signal but not a submissive signal. Both humans and dogs can defuse an aggressive situation by turning their head away and yawning.[1]: 120–122 It is also recognized as a calming signal.[15]

Licking & sniffing: Licking behavior can mean different things depending on the context and should not be simply interpreted as affection. Dogs that are familiar with each other may lick each other's faces in greeting, then they begin to sniff any moist membranes where odors are strongest i.e. mouth, nose, anal regions and urogenital areas. These greetings and identification sniffs may turn to licking as well. For mating behaviors, this is done more vigorously than when greeting each other.[1]: 124 Licking can communicate information about dominance, intentions and state of mind, and like the yawn is mainly a pacifying behavior. All pacifying behaviors contain elements of puppy behavior, including licking. Puppies lick themselves and their litter-mates as part of the cleaning process, and it appears to build bonds. Later in life, licking ceases to be a cleaning function and forms a ritualized gesture indicating friendliness.[1]: 124–125 When stressed, a dog might lick the air, its own lips, or drop down and lick its paws or body.[1]: 126 Lip-licking and sniffing are also recognized as calming signals.[15]

Ears:

Ears erect or slightly forward – attention or alerted.[1]: 130

Ears pulled back flat against the head, teeth bared – anxious dog that will defend itself.[1]: 131

Ears pulled back flat against the head, teeth not bared – submission.[1]: 131

Ears pulled slightly back and slightly splayed – indecision: uneasy suspicion, may turn quickly to aggression.[1]: 131

Ears flickering, slightly forward then slightly back or downward – indecision: more submissive or fearful component.[1]: 131

Ears pulled close to the head to give a "round face" also recognized as a calming signal.[15]

Eyes:

Direct eye-to-eye stare – a threat, expression of dominance, or warning that an attack is about to begin.[1]: 146

Direct eye-to-eye stare to human at the dinner table, followed by direct stare at food– dog wants some food.[1]: 146

Eyes turned away to avoid direct eye contact – breaking off eye contact signals submission;[1]: 147 it is also recognized as a calming signal.[15]

Blinking is also recognized as a calming signal.[15]

Tail:

Tail horizontal, pointing away from the dog but not stiff – attention.[1]: 162

Tail horizontally straight out, stiff, and pointing away from the dog – initial challenge, could lead to aggression.[1]: 162

Tail up, between the horizontal and vertical position – dominant dog.[1]: 162

Tail up and slightly curved over back – confident, dominant dog that feels in control.[1]: 163

Tail held lower than the horizontal but still some distance off from the legs, perhaps with an occasional swishing back and forth – unconcerned, relaxed dog.[1]: 166

Tail down, near hind legs, legs straight, tail swings back and forth slowly – dog feeling unwell, slightly depressed or in moderate pain.[1]: 166

Tail down, near hind legs, hind legs bent inwards to lower the body – timidity, apprehension, insecurity.[1]: 166

Tail tucked between legs – fear, can also be a ritualized pacifying signal to fend off aggression from another dog.[1]: 167

Tail fast wagging – excitement.[1]: 171

Slight tail wag, each swing of only a small size – greeting.[1]: 171

Broad tail wag – friendly.[1]: 172

Broad tail wag, with wide swings that pull the hips from side to side – special happy greeting for someone special.[1]: 172

Slow tail wag with tail at half-mast – unsure of what to do next, insecure.[1]: 173

Tail wagging is also recognized as a calming signal.[15]

Dogs are said to exhibit a left-right asymmetry of the tail when interacting with strangers, and will show the opposite, right-left motion with people and dogs they know.[18]

Body:

Stiff-legged, upright posture or slow, stiff-legged movement forward – dominant dog.[1]: 184

Body slightly sloped forward, feet braced – challenge to a dominant dog, conflict may follow.[1]: 187

Hair bristles on back of shoulders – possible aggression, may also indicate fear and uncertainty.[1]: 187

Lowering the body or cringing while looking up – submission.[1]: 188

Muzzle nudge – occurs when a submissive dog gently pushes the muzzle of the dominant dog, showing acceptance.[1]: 190

Dog sits when approached by another, allowing itself to be sniffed – signals acceptance of dominance but does not signal weakness.[1]: 191

Dog rolls on side or exposes underbelly and completely breaks off eye contact – extreme pacifying or submission signal.[1]: 192

Dog sits with one front paw slightly raised – stress, social fear and insecurity.[1]: 198 It is also recognized as a calming signal.[15]

Dog rolls on its back and rubs its shoulders on the ground – contentment.[1]: 199

Dog crouches with front legs extended, rear body and tail up, facing its playmate directly – classic "play-bow" to commence play.[1]: 200 It is also recognized as a calming signal.[15]

Auditory

Long-distance contact calls are common in Canidae, typically in the form of either barks (termed "pulse trains") or howls (termed "long acoustic streams").[19][20] The long-distance howls of wolves[21] and coyotes[22][23][24] is how dogs communicate.

By the age of four weeks, the dog has developed the majority of its vocalizations. The dog is the most vocal canid and is unique in its tendency to bark in a myriad of situations. Barking appears to have little more communication functions than excitement, fighting, the presence of a human, or simply because other dogs are barking. Subtler signs such as discreet bodily and facial movements, body odors, whines, yelps, and growls are the main sources of actual communication. The majority of these subtle communication techniques are employed at a close proximity to another, but for long-range communication only barking and howling are employed.[25]: Ch10

Barks:

Barking in rapid strings of 3 or 4 with pauses in between, midrange pitch – alerting call, the dog senses something but not yet defined as a threat.[1]: 79

Rapid barking, midrange pitch – basic alarm bark.[1]: 79

Barking still continuously but a bit slower and lower pitch – imminent threat, prepare to defend.[1]: 80

A prolonged string of barks, with moderate to long intervals between each one – lonely, in need of companionship, often exhibited when confined.[1]: 80

One or two sharp, short barks of high or midrange pitch – typical greeting sound, usually replaces the alarm bark when visitor is identified as friendly.[1]: 80

Single sharp short bark, lower midrange pitch – annoyance, used by a mother dog disciplining her puppies or by a dog disturbed from its sleep.[1]: 80

Single short bark, higher midrange pitch – surprised or startled.[1]: 81

Stutter bark, midrange pitch – used to initiate play.[1]: 82

Rising bark – indicates having fun, used during play-fighting or when the owner is about to throw an object.[1]: 83

Growls:

Soft, low-pitched growling that seems to come from the chest – used as a threat by a dominant dog.[1]: 83

Soft growling that is not so low-pitched and seems more obviously to come from the mouth – stay away[1]: 83

Low-pitched growl-bark – growl leading to a bark is both a threat and a call for assistance.[1]: 84

Higher midrange-pitched growl-bark – higher pitch means less confident, frightened but will defend itself.[1]: 84

Undulating growl, going from midrange to high midrange – dog is terrified, it will either defend itself or run away.[1]: 84

Noisy growl, medium and higher pitch, with teeth hidden from view – intense concentration, may be found during play-aggression, however you need to look at the whole body language to be sure.[1]: 84

Howls:

Yip-howl – lonely, in need of companionship.[1]: 86

Howling – indicates the dog is present, or indicating that this is its territory.[1]: 86

Bark-howl, 2-3 barks followed by a mournful howl – dog is relatively isolated, locked away with no companionship, calling for company or a response from another dog.[1]: 87

Baying – can be heard during tracking to call pack-mates to the quarry.[1]: 88

Whines and whimpers:

Whining and whimpers are short, high pitched sounds designed to bring the listener closer to show either fear or submission on the behalf of the whiner or whimperer. These are also the sounds that puppies make as pacifying and soliciting sounds.[1]: 89

Soft whining and whimpering – hurting or scared.[1]: 91

Moan or moan-yodel, lower pitched than whines or whimpers – spontaneous pleasure or excitement.[1]: 91

Single yelp or high-pitched bark – response to sudden, unexpected pain such as a too-hard play bite.[1]: 91

Series of yelps – severe fear or pain.[1]: 91

Screaming: A yelp for several seconds in length much like a human child, then repeated – anguish or agony, a call to the pack-mates for help, is rarely heard.[1]: 92–93

Panting: Panting is an attempt to regulate body temperature. Excitement can raise the body temperature in both humans and dogs. Although not an intentional communication, if the dog pants rapidly but is not exposed to warm conditions then this signals excitement due to stress.[1]: 95

Sighs: Sighs are an expression of emotion, usually when the dog is lying down with its head on its paws. When the eyes are half-closed it signals pleasure and contentment. When the eyes are fully open it signals displeasure, something the dog expected has not happened, often associated with the dinner table and the food that the dog expected to share did not happen.[1]: 96

Olfactory

Dogs have an olfactory sense 40 times more sensitive than a human's and they commence their lives operating almost exclusively on smell and touch.[1]: 247 The special scents that dogs use for communication are called pheromones. Different hormones are secreted when a dog is angry, fearful or confident, and some chemical signatures identify the sex and age of the dog, and if a female is in the estrus cycle, pregnant or recently given birth. Many of the pheromone chemicals can be found dissolved in a dog's urine, and sniffing where another dog has urinated gives the dog a great deal of information about that dog.[1]: 250 Male dogs prefer to mark vertical surfaces with urine and having the scent higher allows the air to carry it further. The height of the marking tells other dogs about the size of the dog, as among canines size is an important factor in dominance.[1]: 251 Dogs (and wolves) not only use urine but also their stools to mark their territories. The anal gland of canines give a particular signature to fecal deposits and identifies the marker as well as the place where the dung is left. A small degree of elevation may be sought, such as a rock or fallen branch, to aid scent dispersal. Scratching the ground after defecating is a visual sign pointing to the scent marking.[1]: 253

Bibliography

- Stanley Coren "How To Speak Dog: Mastering the Art of Dog-Human Communication" 2000 Simon & Schuster, New York.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch Coren, Stanley "How To Speak Dog: Mastering the Art of Dog-Human Communication" 2000 Simon & Schuster, New York.

- ^ Udell, M.A.R., Wynne, C.D.L., 2008. A review of domestic dogs' (Canis familiaris) human-like behaviors: or why behavior analysts should stop worrying and love their dogs. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior 89, 247–261

- ^ Hare, B., 2007. From nonhuman to human mind: what changed and why? Current Directions in Psychological Science 16, 60–64

- ^ Hare, Brian; Tomasello, Michael (2005). "Human-like social skills in dogs?". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 9 (9): 439. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.07.003. PMID 16061417.

- ^ Miklósi, Á., Polgárdi, R., Topál, J., Csányi, V., 2000. Intentional behaviour in dog–human communication: an experimental analysis of “showing” behaviour in the dog. Animal Cognition 3, 159–166

- ^ Miklósi, Á., Topál, J., Csányi, V., 2004. Comparative social cognition: what can dogs teach us? Animal Behaviour 67, 995–1004

- ^ Marler, P., 1970. A comparative approach to vocal learning: song development in white-crowned sparrows. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 71, 1–25

- ^ Lorenz, K., 1965. Evolution and Modification of Behavior. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- ^ Butterworth, George (2003). "Pointing is the royal road to language for babies".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lakatos, Gabriella (2009). "A comparative approach to dogs' (Canis familiaris) and human infants' comprehension of various forms of pointing gestures". Animal Cognition. 12 (4): 621–31. doi:10.1007/s10071-009-0221-4. PMID 19343382.

- ^ Faragó, T; Pongrácz P; Miklósi Á; Huber L; Virányi Z; Range, F (2010). Giurfa, Martin (ed.). "Dogs' Expectation about Signalers' Body Size by Virtue of Their Growls". PLoS ONE. 5 (12): e15175. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515175F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015175. PMC 3002277. PMID 21179521.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "What dogs are saying Scientific American". Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ^ Brian Hare; Vanessa Woods (8 February 2013), "What Are Dogs Saying When They Bark? [Excerpt]", Scientific America, retrieved 17 March 2015

- ^ a b Katherine Sanderson (23 May 2008), "Humans can judge a dog by its growl", Nature, doi:10.1038/news.2008.852, retrieved 17 March 2015 research available here

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Rugaas, Turid (2006). On talking terms with dogs : calming signals (2nd ed.). Wenatchee, Wash.: Dogwise Pub. ISBN 1929242360.

- ^ Eatron, Barry. Dominance in dogs: Fact or Fiction. Dogwise Publishing. ASIN B011T6R50G.

- ^ Rousseau, Steph. "Digging the dirt on dominance". Pet Dog Trainers of Europe Blog.

- ^ "Asymmetric tail-wagging responses by dogs to different emotive stimuli", Current Biology, 17(6), 20 March 2007, pp R199-R201

- ^ Robert L. Robbins, "Vocal Communication in Free-Ranging African Wild Dogs", Behavior, vol. 137, No. 10 (Oct. 2000), pp. 1271-1298.

- ^ J.A. Cohen and M.W. Fox, "Vocalizations in Wild Canids and Possible Effects of Domestication," Behavioural Processes, vol. 1 (1976), pp. 77-92.

- ^ John B. Theberge and J. Bruce Falls, "Howling as a Means of Communication in Timber Wolves," American Zoologist, vol. 7, no. 2 (May 1967), pp. 331-338.

- ^ P.N. Lehner, "Coyote vocalizations: a lexicon and comparisons with other canids," Animal Behavior, vol. 26 (1978) pp. 712-722.

- ^ H. McCarley, "Long distance vocalization of coyotes (Canis latrans)," J. Mamm., vol. 56 (1975), pp. 847-856.

- ^ Charles Fergus, "Probing Question: Why do coyotes howl?" Penn State News (January 15, 2007).

- ^ Fox, Michael W. (1971). Behaviour of Wolves, Dogs, and Related Canids (1st United States ed.). New York: Harper & Row. pp. 183–206. ISBN 0-89874-686-8.

External links