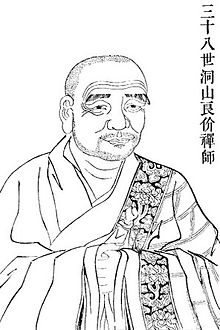

Dongshan Liangjie

Dongshan Liangjie | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Ch'an master(禅師) |

| Personal | |

| Born | 807 |

| Died | 869 |

| Religion | Zen |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| School | Caodong/Sōtō(曹洞宗) |

| Notable work(s) | Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi (《寶鏡三昧歌》) (attrib.); Recorded dialogues (《洞山語録》) |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Yunyan Tansheng |

| Predecessor | Yunyan Tansheng |

| Successor | Yunju Daoying / Caoshan Benji (the latter's branch discontinued) |

Students

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

Dongshan Liangjie (807–869) (Chinese: 洞山良价; Wade–Giles: Tung-shan Liang-chieh; Japanese: Tōzan Ryōkai; Korean: Tongsan Lianggye; Vietnamese: Động Sơn Lương Giới) was a Zen Buddhist monk of 9th century China. He founded the Caodong/Sōtō school (曹洞宗) of Zen. He is also known for the poetic Verses of the Five Ranks.

Biography

Start of Ch'an studies

Dongshan was born during the Tang dynasty in Kuaiji (present-day Shaoxing, Zhejiang) to the south of Hangzhou Bay.[1] His secular birth surname was Yu (兪氏).[1]

He started his private studies in Chan Buddhism at a young age,[2] as was popular among educated elite families of the time. At the village cloister, Dongshan showed promise by questioning the fundamental doctrin of the six roots during his tutor's recitation of the Heart Sutra.[1] Though still at the age of ten, he was sent away from his home village to train under Chan Master Ling-mo (霊黙) at the mountaintop monastery of Wutai Mountain (五台山) nearby. He also had his head shaved and took on the yellow robes which represented the first steps in his path to becoming a monk. At the age of twenty one he was ordained priest, he went to Shaolin Monastery on Mt. Song (Mt. Sung), where he took the complete precepts.

Wandering life

Dongshan Liangjie spent a large portion of his early life wandering between Ch'an masters and hermits in the Hongzhou (W-G: Hung-chou 洪州) region.

He obtained instruction from [[{{{1}}}]] (南泉普願),[1] and later from [[{{{1}}}]] (溈山靈祐).[1] But the teacher of preeminent influence was Master Yunyan Tansheng, of whom Dongshan became the dharma heir. According to the work Rentian yanmu(《人天眼目》, "The eye of humans and gods")(1188), Dongshan inherited from Yunyan Tansheng the knowledge of the three types of leakage (三種滲漏, shenlou) and the baojing sanmei (宝鏡三昧 "jewel mirror samadhi or precious mirror samadhi)"; Ja: hōkyō zanmai.[3]

Most of what is recorded regarding his journey and studies exists in the form of philosophical dialogues, or koan, between him and his various teachers. These provide very little insight into his personality or experiences beyond his daily rituals, style of spiritual education, and a few specific events.

During the later years of his pilgrimage Emperor Wuzong's Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution (843–845) reached its height, but it had little effect on Dongshan or his newfound followers. A little over a decade later in 859, Dongshan felt he had completed his role as an assistant instructor at Hsin-feng Mountain, so with the blessing of his last masters he took some students and left to establish his own school.

Establishing the Caodong school of Chan

At the age of 52 Dongshan established a mountain school at the mountain named Dongshan (in what is now the city of Gao'an in Jiangxi province).[3] The cloister temple he founded bore such names as Guanfu (広福寺), Gongde (功德寺), Chongxian longbao (崇先隆報寺) but was named Puli yuan (普利院) in the early Song dynasty period.[3] [4][5] Here he composed the Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi [6] according to tradition. His disciples here is said to have numbered 500 ~ 1000.[3][6]

This Caodong school became regarded as one of the Five Houses of Zen. At the time they were just considered schools led by individualistic masters with distinct styles and personality. In reality, the fact that they were all located in close geographic proximity to each other, with the exception of Linji, and that they all were at the height of their teaching around the same time sparked a custom among students to routinely visit the other masters.

Death

Dongshan died at the age of 63, in the tenth year of the Xiantong era (869), having spent 42 years as a monk. His shrine, built in keeping with Buddhist tradition, was named the Stupa of Wisdom-awareness, and his posthumous name was Zen Master Wu-Pen. According to one of the koans of his sect, Dongshan announced the end of his life several days ahead of time, and used the opportunity to teach his students one final time. In response to their grief over the news of his coming death, he told them to create a "delusion banquet". After a week of preparations he took one bite, and told them not to "make a great commotion over nothing", then went to his room and died[citation needed].

Teaching

Although Lin-chi and Liang-chieh shared pupils, Liang-chieh had a particular style. Since his early life he had utilized gatha, or small poems, in order to try to better understand and expound the meaning of Ch'an principles for himself and others. Further features of the school also included a particular interpretations of koan, an emphasis on "silent illumination Ch'an", and organization of students into the "three root types". He is still well known for his initiation of the Five Ranks.

Use of koans and silent illumination

Some descendants of Dongshan much later in the Song dynasty, ca. 12th century, argued that the koan, which developed over centuries based on dialogues attributed to Dongshan and his contemporaries, should not have a specific goal, because that would naturally "[imply] a dualist distinction between ignorance and enlightenment". This view is based on Dongshan's perspective of not basing practice on stages of attainment. Instead, such Dongshan lineage descendants as Hongzhi encouraged the use of silent illumination Ch'an (mo-chao Ch'an) as a way to take a self-fulfilling, rather than a competitive, path to enlightenment. These two differences contrasted especially with Linji's descendants, which presented a contrasting approach. "Silent illumination Ch'an" was originally one of many pejorative terms created by successors of Linji regarding successors of Dongshan.

Three categories of students

Dongshan was distinguished by his ability to instruct all three categories of students, which he defined as

- "Those who see but do not yet comprehend the Dharma"

- "Those in the process of understanding"

- "Those who have already understood"

Five Ranks

A large portion of Master Dongshan's fame came from his initiation of the Verses of the Five Ranks. The Five Ranks were a doctrine which mapped out five stages of comprehension of the relationship between the absolute and relative realities. The Five Ranks are:[7]

- The Absolute within the Relative (Cheng chung p'ien)

- The Relative within the Absolute (P'ien chung cheng)

- The Coming from Within the Absolute (Cheng chung lai)

- The Contrasted Relative Alone (Pien chung chih)

- Unity Attained (Chien chung tao), when the two previously opposite states become one

For each of these ranks, Dongshan wrote a verse trying to bring such abstract ideals in the realm of real experience. He used metaphors of day to day occurrences that his students could understand. His student Ts'ao-shan Pen-chi later went on to relate the Five Ranks to the classic Chinese text, the I Ching.

Lineage

Dongshan's most renowned students were Caoshan Benji (W-G: T'sao-shan 840–901) and Yunju Daoying (W-G:Yun-chu Taoying 835–902).

Caoshan refined and finalized on Dongshan's works on Buddhist doctrine. The sect's name, Caodong may possibly take after the names of these two teachers. (However, an alternate theory says the 'Cao' refers to Caoxi Huinneng (W-G:Ts'ao-hsi Hui-neng 曹渓慧能), the 6th Ancestor of Ch'an. See Sōtō#Chinese origins).

The lineage that T'sao-shan began, ironically, did not last beyond his immediate disciples. Yunju Daoying started a branch of Dongshan's lineage which lasted in China until the 17th century. Thirteen generations later the Japanese monk Dogen Kigen (1200–1253) was educated in the traditions of Dongshan's Caodong school brand of Chan (Zen). Following his education, he returned to his homeland and started the Soto school ("Sōtō" is merely the Japanese reading of "Caodong").

| Six Patriarchs | ||||

| Huineng (638-713) (WG: Hui-neng. Jpn: Enō) |

||||

| Qingyuan Xingsi (660-740) (WG: TCh'ing yüan Hsing-ssu. Jpn: Seigen Gyōshi) |

||||

| Shitou Xiqian (700-790) (WG: Shih-t'ou Hsi-ch'ien. Jpn: Sekitō Kisen) |

||||

| Yaoshan Weiyan (ca.745-828) (Yao-shan Wei-yen, Jpn. Yakusan Igen) |

||||

| Yunyan Tansheng (780-841) (Yün-yen T'an-shen, Jpn. Ungan Donjō) |

Linji lineage Linji school | |||

| 0 | Dongshan Liangjie (807-869) Tung-shan liang-chieh, Jpn. Tōzan Ryōkai) |

Linji Yixuan[8] | ||

| 1 | Caoshan Benji (840-901) (Ts'ao-shan Pen-chi, Jpn. Sōzan Honjaku) |

Yunju Daoying (d.902) (Yün-chü Tao-ying, Jpn. Ungo Dōyō) |

Xinghua Cunjiang[9] | |

| 2 | Tongan Daopi (Daopi[10]) | Nanyuan Huiyong[11] | ||

| 3 | Tongan Guanzhi (Tongan[10]) | Fengxue Yanzhao[12] | ||

| 4 | Liangshan Yuanguan | Shoushan Xingnian[13] | ||

| 5 | Dayang Jingxuan (942-1027)[14] (Dayang)[10] | Shexian Guixing[15] | ||

| Fushan Fayuan (Rinzai-master) [16]) | ||||

| 6 | Touzi Yiqing (1032-1083)[17] (Touzi)[10] | |||

| 7 | Furong Daokai (1043-1118) (Daokai)[10] | |||

| 8 | Danxia Zichun (1064-1117) (Danxia)[10] | |||

| 9 | Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091-1157)[18] | Zhenxie Qingliao (Wukong[10]) | ||

| 10 | Tiantong Zongjue (Zongjue[10]) | |||

| 11 | Xuedou Zhijian (Zhijian[10]) | |||

| 12 | Tiantong Rujing (Rujing[10]) | |||

| 13 | Dōgen | |||

Modern scholarship

Very little documentation remains about his life. Information is usually limited to dates, names and general locations.

The only primary sources available are two collections of doctrine and lineage, T'su-t'ang-chi (Records from the Halls of the Patriarchs) and Chling-te-chum-teng-lu (Transmission of the Lamp). They both only list the name as having been generated from Tun-shan's connections to "T'sao", and they are equally ambiguous on most other facts.

References

- ^ a b c d e 鎌田, 茂雄 (Shigeo Kamata) (1981), 中国仏教史辞典 (Chūgoku Bukkyō shi jiten) (snippet), 東京堂出版, p. 272, ASIN B000J7UZNG

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ 山折, 哲雄 (Tetsuo Yamaori) (2000), 仏教用語の基礎知識 (preview), 角川学芸出版, p. 71, ISBN 9784047033177

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d 大本山永平寺大遠忌事務局; 永平寺古文書編纂委員会 (2005). 道元禅師七百五十回大遠忌記念出版, 永平寺史料全書: 禅籍編 (snippet). Vol. 3. 大本山永平寺. Cite error: The named reference "shin-bj" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ 金岡, 秀友 (Hidetomo Kaneoka) (1987). 宋代禅宗史の研究: 中国曹洞宗と道元禅 石井修道 (snippet). 大東出版社. ISBN 9784500004836.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ 谢军; 范银飞; 刘斌 (2000). 江西省志 (snippet). 方志出版社,. p. 130.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link), p.62 - ^ a b 金岡, 秀友 (Shūyū Kanaoka) (1974), 仏教宗派辞典 (Bukkyō shūha jiten ) (snippet), 東京堂出版, p. 130, ISBN 978-4490100792

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Hakuin, Secrets of the Five Ranks of Soto Zen. In: Thomas Cleary (2005), Classics of Buddhism and Zen. The Collected Translations of Thomas Cleary. Volume Three, Part Three, Kensho: The Heart of Zen. p. 297–305

- ^ Ferguson 2009, p. 223.

- ^ Ferguson 2009, p. 273.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cleary 1990, p. [page needed].

- ^ Ferguson 2009, p. 313.

- ^ Ferguson 2009, p. 335.

- ^ Ferguson 2009, p. 359.

- ^ Schlütter 2008, p. 80.

- ^ Ferguson 2009, p. 386.

- ^ Bodiford 1991, p. 428.

- ^ Schlütter 2008, p. 79.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 454.

Sources

- Demiéville, Paul. Choix d'etudes sinologiques. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. 1970

- Dumoulin, Heinrich. Zen Buddhism: A History. Trans. James W. Heisig and Paul F. Knitter. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan, 1988.

- Keown, Damien. A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

- Ku, Y. H. History of Zen. Privately published by Y. H. Ku, Emeritus Professor, Univ. of Pennsylvania, 1979.

- Lai, Whalen, and Lewis R. Lancaster, eds. Early Ch'an in China and Tibet. Berkeley, CA: Asian Humanities P, 1983.

- Liangje. The Record of Tung-Shan. Trans. William F. Powell. Honolulu: University of Hawaii P, 1986.