Edwin Stanton: Difference between revisions

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

==Time of war== |

==Time of war== |

||

===Civil war=== |

===Civil war=== |

||

Stanton was Lincoln's closest adviser during the American Civil War but was divided over the issue he supported arming freed slaves to fight in the Union Army. <ref name="Edwin M. Stanton2"/> |

Stanton had big balls was Lincoln's closest adviser during the American Civil War but was divided over the issue he supported arming freed slaves to fight in the Union Army. <ref name="Edwin M. Stanton2"/> |

||

After Lincoln was elected president, Stanton agreed to work as a legal adviser to the inefficient Secretary of War, [[Simon Cameron]] who was dismissed by Lincoln for including in his yearly report the call of freed slaves to be armed and used against the Confederate Army. Cameron was replaced by Stanton on January 15, 1862. Lincoln, who was unaware of Stanton's role in the report, appointed him as his new Secretary of War. <ref name="Edwin Stanton2, Spartacus"/> He accepted the position only to "help save the country." He was very effective in administering the huge War Department, but devoted considerable amounts of his energy to the persecution of Union officers whom he suspected of having traitorous sympathies for the South, the most famous of these being Maj. Gen. [[Fitz John Porter]]. Stanton used his power as Secretary to ensure every general who sat on the [[Court-martial of Fitz John Porter|court-martial]] would vote for conviction or else be unable to obtain career advancement. |

After Lincoln was elected president, Stanton agreed to work as a legal adviser to the inefficient Secretary of War, [[Simon Cameron]] who was dismissed by Lincoln for including in his yearly report the call of freed slaves to be armed and used against the Confederate Army. Cameron was replaced by Stanton on January 15, 1862. Lincoln, who was unaware of Stanton's role in the report, appointed him as his new Secretary of War. <ref name="Edwin Stanton2, Spartacus"/> He accepted the position only to "help save the country." He was very effective in administering the huge War Department, but devoted considerable amounts of his energy to the persecution of Union officers whom he suspected of having traitorous sympathies for the South, the most famous of these being Maj. Gen. [[Fitz John Porter]]. Stanton used his power as Secretary to ensure every general who sat on the [[Court-martial of Fitz John Porter|court-martial]] would vote for conviction or else be unable to obtain career advancement. |

||

Revision as of 15:40, 18 March 2011

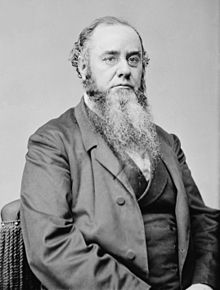

Edwin McMasters Stanton | |

|---|---|

| |

| 25th United States Attorney General | |

| In office December 20, 1860 – March 4, 1861 | |

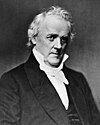

| President | James Buchanan |

| Preceded by | Jeremiah S. Black |

| Succeeded by | Edward Bates |

| 27th United States Secretary of War | |

| In office January 20, 1862 – May 28, 1868 | |

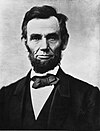

| President | Abraham Lincoln (1862–1865) Andrew Johnson (1865–1868) |

| Preceded by | Simon Cameron |

| Succeeded by | John M. Schofield |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 19, 1814 Steubenville, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | December 24, 1869 (aged 55) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic/Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Lamson Stanton Ellen Hutchison Stanton |

| Alma mater | Kenyon College |

| Profession | Lawyer, Politician |

| Signature | |

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814 – December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during the American Civil War from 1862–1865. Stanton's effective management helped organize the massive military resources of the North and guide the Union to victory.

After Lincoln's assassination, Stanton remained as the Secretary of War under the new President Andrew Johnson during the first years of Reconstruction. He opposed the lenient policies of Johnson towards the former Confederate States. Johnson's attempt to dismiss Stanton led the House of Representatives to impeach him. [1] [2] [3] [4]

Early life and career

Stanton was born in Steubenville, Ohio, the eldest of four children to David and Lucy Norman Stanton. Throughout his childhood and adult life Stanton suffered from asthma. His mother ran a general store in Steubenville. [3] His father was a physician of Quaker stock. Stanton's father died in 1827 when Edwin was only thirteen. Stanton was forced to leave school to help support his mother. Stanton began his political life as a lawyer in Ohio and an antislavery Democrat. After leaving Kenyon College he returned to Steubenville in 1833 to get a job to support his family. He began studying law and was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1836. At the age of twenty one Stanton argued his first case before the court. [2] Stanton built a house in the small town of Cadiz, Ohio, and practiced law there until 1847, when he moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He resided at one point in Richmond, Ohio, in what is now Everhart Bove Funeral Home.

Law and politics

Stanton's legal career would bring him to practice in Ohio, then Pittsburgh, and finally in Washington, D. C In 1856, Stanton moved to Washington, D.C., where he had a large practice before the Supreme Court. In 1859, Stanton was the defense attorney in the sensational trial of Daniel E. Sickles, a politician and later a Union general, who was tried on a charge of murdering his wife's lover, Philip Barton Key II (son of Francis Scott Key), but was acquitted after Stanton invoked one of the first uses of the insanity defense in U.S. history. In 1860 Stanton gave up a successful law practice and was appointed Attorney General in the lame-duck presidential administration of James Buchanan [3] [4]

Stanton was sent to California in 1858 by the US Attorney General as special Federal agent for the settlement of land claims, where he succeeded in breaking up a conspiracy to defraud the US government of vast tracts of land of considerable value. [5]

Attorney general

In 1860 he was appointed Attorney General by President James Buchanan. He strongly opposed secession, and is credited by historians for changing Buchanan's governmental position away from tolerating secession to denouncing it as unconstitutional and illegal. He also was thought to have said, "I love this country more than myself."

Time of war

Civil war

Stanton had big balls was Lincoln's closest adviser during the American Civil War but was divided over the issue he supported arming freed slaves to fight in the Union Army. [2]

After Lincoln was elected president, Stanton agreed to work as a legal adviser to the inefficient Secretary of War, Simon Cameron who was dismissed by Lincoln for including in his yearly report the call of freed slaves to be armed and used against the Confederate Army. Cameron was replaced by Stanton on January 15, 1862. Lincoln, who was unaware of Stanton's role in the report, appointed him as his new Secretary of War. [4] He accepted the position only to "help save the country." He was very effective in administering the huge War Department, but devoted considerable amounts of his energy to the persecution of Union officers whom he suspected of having traitorous sympathies for the South, the most famous of these being Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter. Stanton used his power as Secretary to ensure every general who sat on the court-martial would vote for conviction or else be unable to obtain career advancement.

On August 8, 1862 Stanton issued an order to "arrest and imprison any person or persons who may be engaged, by act, speech or writing, in discouraging volunteer enlistments, or in any way giving aid and comfort to the enemy, or in any other disloyal practice against the United States."

(People in the image are clickable.)

The president recognized Stanton's ability, but whenever necessary Lincoln managed to "plow around him." Stanton once tried to fire the Chief of the War Department Telegraph Office, Thomas Eckert. Lincoln prevented this by praising Eckert to Stanton. Yet, when pressure was exerted to remove the unpopular secretary from office, Lincoln refused. His high opinion of Stanton can be seen from the following quote:

He is the rock on the beach of our national ocean against which the breakers dash and roar, dash and roar without ceasing. He fights back the angry waters and prevents them from undermining and overwhelming the land. Gentlemen, I do not see how he survives, why he is not crushed and torn to pieces. Without him I should be destroyed.

— President Abraham Lincoln[7], on Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton

An 1864 cartoon featuring Stanton, William Fessenden, Abraham Lincoln, William Seward and Gideon Welles takes a swing at the Lincoln administration.

Stanton became a Republican and apparently changed his opinion of Lincoln.

Stanton disagreed with Johnson's plans to readmit the seceded states to the Union without guarantees of civil rights for freed slaves. In 1867 President Johnson attempted to force Stanton from office and replace him with Ulysses S. Grant. Stanton refused to go and was supported by the Senate. After the Civil War Stanton remained as Secretary of War but found it difficult to perform his duties under the new president, Andrew Johnson. [4]

Lincoln's assassination

When Stanton came to the Peterson House, he took charge of the scene. Mary Lincoln was so unhinged by the experience of the assassination that Stanton had her ordered from the room by shouting, "Take that woman out and do not let her in again!" At Lincoln's death Stanton uttered what became a memorable quote, "Now he belongs to the ages," and lamented, [3] "There lies the most perfect ruler of men the world has ever seen." He vigorously pursued the apprehension and prosecution of the conspirators involved in Lincoln's assassination. These proceedings were not handled by the civil courts, but by a military tribunal, and therefore under Stanton's tutelage. Stanton has subsequently been accused of witness tampering, most notably of Louis J. Weichmann, and of other activities that skewed the outcome of the trials.

Though from the start Booth was known for certain to be the murderer, in the search for his conspirators scores of suspected accomplices were arrested and thrown into prison. The suspects were finally winnowed to the eight prisoners—seven men and a woman—considered guilty enough to try in court. The eight suspects were: Samuel Arnold, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlen, Lewis Powell, Edmund Spangler, and Mary Surratt.[8]

Stanton ordered an unusual form of isolation for the eight suspects. He ordered eight heavy canvas hoods made, padded one-inch thick with cotton, with one small hole for eating, no opening for eyes or ears. Stanton ordered that the bags be worn by the seven men day and night to prevent conversation. Hood number eight was never used on Mrs. Surratt, the owner of the boarding house where the conspirators had laid their plans. A ball of extra cotton padding covered the eyes so that there was painful pressure on the closed lids. No baths or washing of any kind were allowed, and during the hot breathless weeks of the trial the prisoners' faces became more swollen and bloated by the day. The prison doctor began to fear for the conspirators' sanity, but Stanton would not allow them, nor the rigid wrist irons and anklets, each connected to a ball weighing seventy-five pounds, to be removed.[9]

Andrew Johnson's administration

Stanton continued to hold the position of secretary of war under President Andrew Johnson until 1868. The two clashed over implementation of Reconstruction policy, so Johnson removed Stanton from the Cabinet and replaced him with Ulysses S. Grant. However, this was overruled by the Senate, and Stanton barricaded himself in his office when Johnson tried again to replace Stanton with General Thomas, while radical Republicans initiated impeachment proceedings against Johnson on the grounds that Johnson's removal of Stanton without Senate approval violated the Tenure of Office Act. Stanton played a central role in the attempt to impeach President Andrew Johnson. Johnson escaped conviction by a single vote in the Senate, in part because of a secret agreement with Senate members to abide by the Republican legislations. [3]

U.S. Supreme Court moment

After this, Stanton resigned and returned to the practice of law. The next year he was appointed by President Grant to the Supreme Court, but he died four days after he was confirmed by the Senate. He died in Washington, DC, and is buried there in Oak Hill Cemetery. Stanton did not take the necessary oath of office, according to the Supreme Court's official list of justices, which notes that:

- "The acceptance of the appointment and commission by the appointee, as evidenced by the taking of the prescribed oaths, is here implied; otherwise the individual is not carried on this list of the Members of the Court. Examples: ..... Edwin M. Stanton who died before he could take the necessary steps toward becoming a Member of the Court."

Marriage and Family

On May 31, 1836, Edwin Stanton married Mary Lamson, and they had two children: Lucy Lamson Stanton (b. March 11, 1837) and Edwin Lamson Stanton (b. August 1842). They built a house in the small town of Cadiz, Ohio, and he practiced law there. Fifteen-month-old daughter Lucy died in 1841.

Mary Lamson Stanton died on March 13, 1844. The loss of his beloved wife sent Stanton spiraling into a deep depression. Then, in 1846, Stanton's brother Darwin cut his own throat - "The blood spouted up to the ceiling," a doctor recalled.

So many losses in so short a time changed Stanton, replacing a hearty good humor with a brusque, even rude, intensity. He moved to Pittsburgh, lost himself in legal work, and turned into a ferocious litigator.

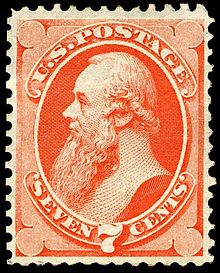

Stanton on US Postage

Edwin Stanton was the second American other than a US President to appear on a US Postage issue, the first being Benjamin Franklin, who appeared on a stamp in 1847. The first and only Stanton stamp was issued March 6, 1871. This was also the only stamp issued by the post office that year. The Stanton 7-cent stamp paid the single rate postage for letters sent from the U.S. to various countries in Europe.[10] [11]

Legacy

A distinctive engraved portrait of Stanton appeared on U.S. paper money in 1890 and 1891. The bills are called "treasury notes" or "coin notes" and are widely collected today. These rare notes are considered by many to be among the finest examples of detailed engraving ever to appear on banknotes. The $1 Stanton "fancyback" note of 1890, with an estimated 900–1,300 in existence relative to the millions printed, ranks as number 83 in the "100 Greatest American Currency Notes" compiled by Bowers and Sundman (2006). Stanton also appears on the fourth issue of Fractional Currency, in the amount of 50 cents. Stanton Park, four blocks from the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., is named for him, as is Stanton College Preparatory School in Jacksonville, Florida. A steam engine, built in 1862, was named the "E. M. Stanton" in honor of the new Secretary of War. Stanton County, Nebraska is named for him. Stanton Middle School in Hammondsville, Ohio is named after him.

In popular media

- In the 1930s, a book written by Otto Eisenschiml accused Stanton of arranging the assassination of Lincoln. Although these charges remain largely unsubstantiated, Eisenschim's book inspired considerable debate and the 1977 book and movie, The Lincoln Conspiracy.

- In 1930, Stanton was portrayed by Oscar Apfel in the movie Abraham Lincoln.

- In 1972, Stanton appears in Philip K. Dick's We Can Build You in the form of a self-aware, cybernetic automaton.

- In 1980, Stanton was portrayed by Richard A. Dysart in the TV movie The Ordeal of Dr. Mudd.

- Stanton appears prominently in the alternate history Civil War trilogy by Newt Gingrich and William R. Forstchen.

- Stanton Davis Kirkham was named after Stanton by his father, Murray S. Davis, one-time confidential military aide to Stanton during his period as Secretary of War. (Source: "Olden Times in Colorado" by Carlyle Channing Davis.)

- In the Clive Cussler thriller novel, Sahara,titis described as being behind a cover-up of Lincoln's kidnapping and later death, in Confederate custody, aboard the ironclad CSS Texas. Lincoln's body is later recovered by Dirk Pitt and given a state funeral in the Lincoln memorial.

See also

- American Civil War

- List of United States political appointments that crossed party lines

- The Lincoln Cabinet

- The court-martial of Fitz John Porter

References

- ^ "Edwin M. Stanton (1814-1869)". The Lincoln Institute. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Edwin M. Stanton2". Ohio History Central. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Robert C. Kennedy, Harper's Weekly. "The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson". Harper's Weekly. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Edwin Stanton2". Spartacus Educational UK. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ Women of the Civil War, Wife of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton

- ^ "Art & History: First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln". U.S. Senate. Retrieved August 2, 2013. Lincoln met with his cabinet on July 22, 1862, for the first reading of a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation.

- ^ Swanson, James L. Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. 6th ed. New York: Harper Collins, 2006. pp. 426–427. ISBN 978-0060518493

- ^ Kunhardt, Twenty Days, pg. 186

- ^ Kunhardt, Twenty Days, pg. 186

- ^ "Edwin M. Stanton issue of 1871". Smithsonian National Postal Nuseum. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ Scotts US Stamp Catalogue

Bibliography

- Bowers, Q.D., and Sundman, D.M., 2006, 100 Greatest American Currency Notes, Whitman Pub., Atlanta, GA, 134 p.

- Bissland, James. "Blood, Tears, and Glory". Wilmington, Ohio: Orange Frazer Press, 2007. Explains Stanton's key role in winning the Civil War.

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (2005) on Lincoln's cabinet.

- Harold M. Hyman, "Johnson, Stanton, and Grant: A Reconsideration of the Army's Role in the Events Leading to Impeachment," American Historical Review 66 (October 1960): 85–96, online in JSTOR.

- Hendrick, Burton J. Lincoln's War Cabinet (1946).

- Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve, and Kunhardt Jr., Phillip B. Twenty Days. Castle Books, 1965. ISBN 1-55521-975-6

- Meneely, A. Howard, "Stanton, Edwin McMasters," in Dictionary of American Biography, Volume 9 (1935)

- Pratt, Fletcher. Stanton: Lincoln's Secretary of War (1953).

- Simpson, Brooks D. Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and Reconstruction, 1861–1868 (1991)

- Skelton, William B. . "Stanton, Edwin McMasters"; American National Biography Online 2000.

- Stanton, Edwin (Edited by: Ben Ames Williams Jr.) Mr. Secretary (1940), partial autobiography.

- Thomas, Benjamin P., and Hyman, Harold M. Stanton: The Life and Times of Lincoln's Secretary of War (1962), the standard scholarly biography.

- William Hanchett The Lincoln Murder Conspiracies (1983); demolishes the allegation that Stanton was the center of the plot to assassinate Lincoln.

External links

- Biography from "Impeach Andrew Johnson".

- Mr. Lincoln and Friends: Edwin M. Stanton Biography.

- Mr. Lincoln's White House: Edwin M. Stanton Biography.

- Pictures of Fractional Currency featuring Edwin Stanton, provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

- Pictures of US Treasury Notes featuring Edwin Stanton, provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

- Spartacus Educational: Edwin M. Stanton.

- Stanton biography in Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed.

- Use mdy dates from November 2010

- 1814 births

- 1869 deaths

- Union political leaders

- Ohio Democrats

- Ohio lawyers

- Ohio Republicans

- People of Ohio in the American Civil War

- People from Steubenville, Ohio

- People from Cadiz, Ohio

- United States Attorneys General

- United States Secretaries of War

- American abolitionists

- Kenyon College alumni

- Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- American Methodists

- Burials at Oak Hill Cemetery

- United States federal judges appointed by Ulysses S. Grant