Fin whale

| Fin Whale | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Fin Whale surfaces in the Kenai Fjords, Alaska | |

| |

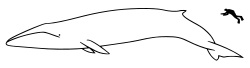

| Size comparison against an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | B. physalus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Balaenoptera physalus | |

| |

| Fin Whale range | |

The Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus), also called the Finback Whale or Razorback or Common Rorqual, is a marine mammal belonging to the suborder of baleen whales. It is the second largest whale and the second largest living animal after the Blue Whale,[2] growing to nearly 27 metres (88 ft) long.[2]

Long and slender, the Fin Whale's body is brownish-gray with a paler underside. There are at least two distinct subspecies: the Northern Fin Whale of the North Atlantic, and the larger Antarctic Fin Whale of the Southern Ocean. It is found in all the world's major oceans, from polar to tropical waters. It is absent only from waters close to the ice pack at both the north and south poles and relatively small areas of water away from the open ocean. The highest population density occurs in temperate and cool waters.[3] Its food consists of small schooling fish, squid and crustaceans including mysids and krill.

Like all other large whales, the Fin Whale was heavily hunted during the twentieth century and is an endangered species. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) has issued a moratorium on commercial hunting of this whale,[4] although Iceland and Japan have announced intentions to resume hunting, the latter country stating it will kill a quota of 50 whales for the 2008 season. Collisions with ships and noise from human activity are also significant threats to the recovery of the species.

Taxonomy

The Fin Whale has long been known to taxonomists, first described by Frederick Martens in 1675 and then again by Paul Dudley in 1725. These descriptions were used as the basis of Carolus Linnaeus' Balaena physalus (1758).[5] The Comte de Lacepede reclassified it as Balaenoptera physalus early in the nineteenth century. The specific name comes from the Greek physa, meaning blows.

Fin Whales are rorquals (family Balaenopteridae), a family that includes the Humpback Whale, the Blue Whale, the Bryde's Whale, the Sei Whale and the Minke Whale. The family Balaenopteridae diverged from the other families of the suborder Mysticeti as long ago as the middle Miocene.[6] However, it is not known when the members of these families diverged from each other. Hybridization between the Blue Whale and the Fin Whale is known to occur at least occasionally in the North Atlantic[7] and in the North Pacific.[8]

As of 2006, there are two named subspecies, each with distinct physical features and vocalizations. B. p. physalus (Linnaeus 1758), or Northern Fin Whale, is found in the North Atlantic, and B. p. quoyi (Fischer 1829), or Antarctic Fin Whale, is found in the Southern Ocean.[9] Most experts consider the Fin Whales of the North Pacific to be a third unnamed subspecies.[3] On a global scale, the three groups rarely mix, if at all.

Description and behaviour

The Fin Whale is usually distinguished by its great length and slender build. The average size of males and females is 19 and 20 metres (62 and 66 ft), respectively. Subspecies in the northern hemisphere are known to reach lengths of up to 24 metres (79 ft), and the Antarctic subspecies reaches lengths of up to 26.8 metres (88 ft).[2] A full-sized adult has never been weighed, but calculations suggest that a 25 metre (82 ft) animal could weigh as much as 70,000 kilograms (154,000 lb). Full physical maturity is not attained until between 25 and 30 years, although Fin whales have been known to live to 94 years of age.[10] A newborn Fin Whale measures about 6.5 metres (21 ft) in length and weighs approximately 1,800 kilograms (4,000 lb).[11] The animal's large size aids in identification, and it is usually only confused with the Blue Whale, the Sei Whale, or, in warmer waters, Bryde's Whale.

The Fin Whale has a brownish grey top and sides and a whitish underside. It has a pointed snout, paired blowholes, and a broad, flat rostrum. Two lighter-coloured chevrons begin midline behind the blowholes and slant down the sides toward the tail on a diagonal upward to the dorsal fin, sometimes re-curving forward on the back.[2] It has a large white patch on the right side of the lower jaw, while the left side of the jaw is grey or black.[11] This type of asymmetry can be seen occasionally in Minke Whales, but the Fin Whale's asymmetry is universal and thus is unique among cetaceans and is one of the keys to making a full identification. It was hypothesized to have evolved because the whale swims on its right side when surface lunging and it often circles to the right while at the surface above a prey patch. However, the whales just as often circle to the left. There is no accepted hypothesis to explain the asymmetry.[12]

The whale has a series of 56 – 100 pleats or grooves along the bottom of the body that run from the tip of the chin to the navel that allow the throat area to expand greatly during feeding. It has a curved, prominent (60 cm, 24 in) dorsal fin about three-quarters of the way along the back. Its flippers are small and tapered, and its tail is wide, pointed at the tip, and notched in the centre.[2]

When the whale surfaces, the dorsal fin is visible soon after the spout. The spout is vertical and narrow and can reach heights of 6 metres.[11] The whale will blow one to several times on each visit to the surface, staying close to the surface for about one and a half minutes each time. The tail remains submerged during the surfacing sequence. It then dives to depths of up to 250 metres (820 ft), each dive lasting between 10 and 15 minutes. Fin Whales have been known to leap completely out of the water.[11]

Life history

Mating occurs in temperate, low-latitude seas during the winter, and the gestation period is eleven months to one year. A newborn weans from its mother at 6 or 7 months of age when it is 11 or 12 metres (36 to 39 ft) in length, and the calf follows the mother to the winter feeding ground. Females reproduce every 2 to 3 years, with as many as 6 foetuses being reported, but single births are far more common. Females reach sexual maturity at between 3 and 12 years of age.[11]

Feeding

The Fin Whale is a filter-feeder, feeding on small schooling fish, squid and crustaceans including mysids and krill.[11] It feeds by opening its jaws while swimming at a relatively high speed, 11 kilometres per hour (7 mi/hr) in one study,[13] which causes it to engulf up to 70 cubic metres (18,000 gallons) of water in one gulp. It then closes its jaws and pushes the water back out of its mouth through its baleen, which allows the water to leave while trapping the prey. An adult has between 262 and 473 baleen plates on each side of the mouth. Each plate is made of keratin that frays out into fine hairs on the ends inside the mouth near the tongue. Each plate can measure up to 76 centimetres (30 inches) in length and 30 centimetres (12 inches) in width.[2] The whale routinely dives to depths of more than 200 metres (650 ft), where it executes an average of four "lunges", where it feeds on aggregations of krill. Each gulp provides the whale with approximately 10 kilograms (20 lb) of krill.[13] One whale can consume up to 1,800 kilograms (4,000 lb) of food a day,[2] leading scientists to conclude that the whale spends about three hours of each feeding to meet its energy requirements, roughly the same as humans. If the prey patches aren't dense enough or located too deep in the water, the whale has to spend a larger portion of its day searching for food.[13] Fin whales have also been observed circling schools of fish at high speed, compacting the school into a tight ball, then turning on its side before engulfing the fish.[2]

Behaviour

The Fin Whale is one of the fastest cetaceans and can sustain speeds of 37 kilometres per hour (23 mi/hr, 20 knots),[11] and bursts in excess of 40 kilometres per hour (25 mi/hr, 22 knots) have been recorded, earning the Fin Whale the nickname "the greyhound of the deep".[14]

Fin Whales are more gregarious than other rorquals, and often live in groups of 6 – 10 individuals, although on the feeding grounds aggregations of up to 100 animals may be observed.[10]

Vocalizations

| Multimedia relating to the Fin Whale Note that the whale calls have been sped up 10x from their original speed.

|

| Template:Multi-listen start |

Like other whales, the male Fin Whale has been observed to make long, loud, low-frequency sounds.[11] The vocalizations of Blue and Fin Whales are the lowest known sounds made by any animal.[15] Most sounds are frequency-modulated (FM) down-swept infrasonic pulses from 16 to 40 hertz frequency (the range of sounds that most humans can hear falls between 20 hertz and 20 kilohertz). Each sound lasts between one to two seconds, and various combinations of sounds occur in patterned sequences lasting 7 to 15 minutes each. These sequences are then repeated in bouts lasting up to many days.[16] The vocal sequences have source levels of up to 184 – 186 decibels relative to 1 micropascal at a reference distance of one metre, and can be detected hundreds of miles from their source.[17]

When Fin Whale sounds were first recorded, researchers did not realize that these unusually loud, long, pure, and regular sounds were being made by whales. They first investigated the possibilities that the sounds were due to equipment malfunction, geophysical phenomena, or part of a Soviet Union scheme for detecting enemy submarines. Eventually, biologists demonstrated that the sounds were the vocalizations of Fin Whales.[15]

Direct association of these vocalizations with the reproductive season for the species and that only males make the sounds point to these vocalizations as possible reproductive displays.[18][19] Over the past 100 years, the dramatic increase in ocean noise from shipping and naval activity may have slowed the recovery of the Fin Whale population, by impeding communications between males and sexually receptive females.[20]

Habitat and migration

Like many of the large rorquals, the Fin Whale is a cosmopolitan species. It is found in all the world's major oceans, and in waters ranging from the polar to the tropical. It is absent only from waters close to the ice pack at both the north and south extremities and relatively small areas of water away from the large oceans, such as the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the eastern part of the Mediterranean and the Baltic Sea. The highest population density occurs in temperate and cool waters. It is less densely populated in the hottest, equatorial regions. It prefers deep waters beyond the continental shelf to shallow waters.

The North Atlantic Fin Whale has an extensive distribution, occurring from the Gulf of Mexico and Mediterranean Sea, northward to the edges of the Arctic ice pack. In general, Fin Whales are more common north of approximately 30°N latitude, but considerable confusion arises about their occurrence south of 30°N latitude because of the difficulty in distinguishing Fin Whales from Bryde's Whales.[21] Extensive ship surveys have led researchers to conclude that the summer feeding range of Fin Whales in the western North Atlantic was mainly between 41°20'N and 51°00'N, from shore seaward to the 1,000 fathom contour.[22]

Summer distribution of Fin Whales in the North Pacific is the immediate offshore waters from central Baja California to Japan, and as far north as the Chukchi Sea bordering the Arctic Ocean.[23] They occur in high densities in the northern Gulf of Alaska and southeastern Bering Sea between May and October, with some movement through the Aleutian passes into and out of the Bering Sea.[24] Several whales tagged between November and January off southern California were killed in the summer off central California, Oregon, British Columbia, and in the Gulf of Alaska.[23] Fin Whales have been observed feeding in Hawaiian waters in mid-May, and several winter sightings have been made there.[25] Some researchers have suggested that the whales migrate into Hawaiian waters primarily in the autumn and winter.[26]

Although fin whales are certainly migratory, moving seasonally in and out of high-latitude feeding areas, the overall migration pattern is not well understood. Acoustic readings from passive-listening hydrophone arrays indicate a southward migration of the North Atlantic Fin Whale occurs in the autumn from the Labrador-Newfoundland region, south past Bermuda, and into the West Indies.[27] One or more populations of Fin Whales are thought to remain year-round in high latitudes, moving offshore, but not southward in late autumn.[27] In the Pacific, migration patterns are difficult to understand. Although some Fin Whales are apparently present in the Gulf of California year-round, there is a significant increase in their numbers in the winter and spring.[28] Antarctic Fin Whales migrate seasonally from relatively high-latitude Antarctic feeding grounds in the summer to low-latitude breeding and calving areas in the winter. The location of winter breeding areas is still unknown, since these whales tend to migrate in the open ocean and thus exact locations have been difficult to determine.[3]

Abundance and trends

The lack of understanding of the migration pattern of the Fin Whale combined with population surveys that are often contradictory makes estimating the historical and current population levels of the whale difficult and contentious. Due to a long history of hunting this whale, pre-exploitation population levels are difficult or impossible to accurately determine, yet estimates are important to measure the rate of recovery of the species.

North Atlantic

In the North Atlantic, Fin Whales are defined by the International Whaling Commission to exist in one of seven discrete population zones: Nova Scotia, Newfoundland-Labrador, West Greenland, East Greenland-Iceland, North Norway, West Norway-Faroe Islands, and British Isles-Spain-Portugal. Results of mark-and-recapture surveys have indicated that some movement occurs across the boundaries of these population zones, suggesting that each zone is not entirely discrete and that some immigration and emigration does occur.[22] J. Sigurjónsson estimated in 1995 that a total pre-exploitation population size of the Fin Whale in the entire North Atlantic ranged between 50,000 and 100,000 animals,[29] but his research is criticized for not providing supporting data and an explanation of his reasoning.[3] In 1977, D.E. Sergeant suggested a "primeval" aggregate total of 30,000 to 50,000 Fin Whales throughout the North Atlantic.[30] Of that number, about 8,000 to 9,000 would have resided in the Newfoundland and Nova Scotia areas, with whales summering in U.S. waters south of Nova Scotia presumably not having been taken fully into account.[31][3] J.M. Breiwick estimated that the "exploitable" (above the legal size limit of 50 feet) component of the Nova Scotia population was 1,500 to 1,600 animals in 1964, reduced to only about 325 in 1973.[32] Two aerial surveys have been conducted in Canadian waters since the early 1970s, giving numbers of 79 to 926 whales on the eastern Newfoundland-Labrador shelf in August 1980,[33] and a few hundred in the northern and central Gulf of St. Lawrence in August 1995 – 1996.[34] Estimates of the number of Fin Whales in the waters off West Greenland in the summer range between 500 and 2,000,[35] and in 1974, Jonsgard considered the Fin Whales off Western Norway and the Faroe Islands to "have been considerably depleted in postwar years, probably by overexploitation".[36] The population around Iceland appears to have fared much better, and in 1981, the population appeared to have undergone only a minor decline since the early 1960s.[37] Surveys during the summers of 1987 and 1989 produced estimates in the order of 10,000 to 11,000 Fin Whales between East Greenland and Norway.[38] This shows a substantial recovery when compared to a survey in 1976 showing an estimate of 6,900 whales, which was considered to be a "slight" decline since 1948 levels.[39] Estimates of population levels in the British Isles-Spain-Portugal area in summer have ranged from 7,500[40] to more than 17,000.[41] In total, the aggregate population level of the North Atlantic Fin Whale is estimated to be between 40,000[42] and 56,000[7] individuals.

North Pacific

The total historical North Pacific Fin Whale population has been estimated at 42,000 to 45,000 before the start of whaling. Of this, the population in the eastern portion of the North Pacific was estimated to be 25,000 to 27,000.[43] By 1975, the population estimate had declined to between 8,000 and 16,000.[44][45] Surveys conducted in 1991, 1993, 1996, and 2001 produced estimates of between 1,600 and 3,200 Fin Whales off California and 280 to 380 Fin Whales off Oregon and Washington.[46] The miniumum estimate for the California-Oregon-Washington population, as defined in the U.S. Pacific Marine Mammal Stock Assessments: 2005, is about 2,500.[47] Surveys near the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea indicated a substantial increase in the local abundance of Fin Whales between 1975 – 1978 and 1987 – 1989.[48] In 1984, the entire North Pacific Fin Whale population was estimated to be at less than 38% of its historic carrying capacity.[49]

Antarctica

Relatively little is known about the historical and current population levels of the Antarctic Fin Whale. The IWC officially estimates that the pre-whaling population of the Fin Whale in the southern hemisphere was 400,000 whales, and that the population in 1979 was 85,200.[50] Both the current and historical estimates should be considered as poor estimates because the methodology and data used in the study are known to be flawed.[3] Other estimates cite current population levels of no more than 5,000 whales and possibly as low as 2,000 to 3,000.[11] As of 2006, there is no scientifically accepted estimate of current population or trends in abundance.[3]

Human interaction

In the 19th century, the Fin Whale was occasionally hunted by the sailing-vessel whalers, but it was relatively safe because of its quick speed and the fact that it prefers the open sea. However, the introduction of steam-powered boats in the second half of that century and harpoons that exploded on impact made it possible to kill and secure Blue Whales, Fin Whales, and Sei Whales on an industrial scale. As other whale species became over-hunted, the whaling industry turned to the still-abundant Fin Whale as a substitute.[51] It was primarily hunted for its blubber, oil, and baleen. Approximately 704,000 Fin Whales were caught in Antarctic whaling operations alone between 1904 and 1975.[52] After the introduction of factory ships with stern slipways in 1925, the number of whales taken per year increased substantially. In 1937 alone, over 28,000 Fin Whales were taken. From 1953 to 1961, whaling of the species averaged around 25,000 per year. By 1962, Sei Whale catches began to increase as Fin Whales became scarce. By 1974, fewer than 1,000 Fin Whales were being caught each year. The IWC prohibited the taking of Fin Whales from the southern hemisphere in 1976.[52] In the North Pacific, a reported total of approximately 46,000 Fin Whales were killed by commercial whalers between 1947 and 1987.[53] Acknowledgement that the Soviet Union engaged in the illegal killing of protected whale species in the North Pacific means that the reported catch data is incomplete.[54] The Fin Whale was given full protection from commercial whaling by the IWC in the North Pacific in 1976, and in the North Atlantic in 1987, with the exception of small aboriginal catches and catches for research purposes.[11] All populations worldwide remain listed as endangered species by the US Fish & Wildlife Service and the International Conservation Union Red List, and the Fin Whale is on Appendix 1 of CITES.[1][11][55][56]

The Fin Whale is hunted in the Northern Hemisphere in Greenland, under the International Whaling Commission's procedure for aboriginal subsistence whaling. Meat and other products from whales killed in these hunts are widely marketed within the Greenland economy, but export is illegal. The IWC has set a quota of 19 Fin Whales per year for Greenland despite concern about uncertainty of current population levels. Iceland and Norway are not bound by the IWC's moratorium on commercial whaling because both countries filed objections to the moratorium.[3] In October 2006, Iceland's fisheries ministry authorized the hunting of nine Fin Whales through August 2007.[57] In the southern hemisphere, Japan has targeted Fin Whales in its Antarctic Special Permit whaling program for the 2005 – 2006 and 2006 – 2007 seasons at 10 whales killed per year.[58] The proposal for 2007 – 2008 and the subsequent 12 seasons includes 50 Fin Whales per year.[3]

Collisions with ships are an additional major cause of Fin Whale mortality. In some areas, they represent a substantial portion of the strandings of large whales. Most lethal and serious injuries are caused by large, fast-moving ships over or near the continental shelf.[59]

See also

References

- ^ a b Template:IUCN2006 Database entry includes justification for why this species is endangered

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Balaenoptera physalus Fin Whale". MarineBio.org. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i National Marine Fisheries Service (2006). Draft recovery plan for the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) (pdf). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Marine Fisheries Service.

- ^ "Revised Management Scheme". International Whaling Commission. Retrieved 2006-11-07.

- ^ Template:La icon Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 824.

- ^ Gingerich, P. (2004). "Whale Evolution". McGraw-Hill Yearbook of Science & Technology. The McGraw Hill Companies. ISBN 0071427848.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b Bérubé, M. (1998). "A new hybrid between a blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus, and a fin whale, B. physalus: frequency and implications of hybridization". Mar. Mamm. Sci. 14: 82–98.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Doroshenko, V.N. (1970). "A whale with features of the fin and blue whale (in Russian)". Izvestia TINRO. 70: 225–257.

- ^ "Balaenoptera physalus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. 23 October.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ a b Martin, Anthony R. (1991). Whales and dolphins. London: Salamander Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fox, David (2001). "Balaenoptera physalus (fin whale)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- ^ Tershy, B. R. (1992). "Asymmetrical pigmentation in the fin whale: a test of two feeding related hypotheses". Marine Mammal Science. 8 (3): 315–318.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Lin, Brian (2007-06-07). "Whale Has Super-sized Big Gulp". University of British Columbia. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Fin Whale". nature.ca: Canadian Museum of Nature. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- ^ a b Payne, Roger (1995). Among Whales. New York: Scribner. p. 176. ISBN 0-684-80210-4.

- ^ "Finback Whales". Bioacoustics Research Program, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ^ W. J. Richardson, C. R. Greene, C. I. Malme and D. H. Thomson, Marine Mammals and Noise (Academic Press, San Diego, 1995).

- ^ Croll, D.A. (2002). "Only male fin wales sing loud songs" (pdf). Nature. 417 (6891): 809.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Watkins, W. "The 20-Hz signals of finback whales (Balaenoptera physalus)". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 82 (6): 1901–1902.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Segelken, R. (2002-06-19). "Humanity's din in the oceans could be blocking whales' courtship songs and population recovery". Cornell University.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|accessed=ignored (help) - ^ Mead, J.G. (1977). "Records of Sei and Bryde's whales from the Atlantic Coast of the United States, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean". Rep. int. Whal. Commn. Spec. Iss. 1: 113–116. ISBN 0-906975-03-4.

- ^ a b Mitchell, E. (1974). "Present status of Northwest Atlantic fin and other whale stocks". In W.E. Schevill (ed.) (ed.). The Whale Problem: A Status Report. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 108–169. ISBN 0-674-95075-5.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Rice, D.W. (1974). "Whales and whale research in the eastern North Pacific". In W.E. Schevill (ed.) (ed.). The Whale Problem: A Status Report. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 170–195. ISBN 0-674-95075-5.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Reeves, R.R. (1985). "Whaling in the Bay of Fundy". Whalewatcher. 19 (4): 14–18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mobley, J.R., Jr. (1996). "Fin whale sighting north of Kaua'i, Hawai'i". Pacific Science. 50 (2): 230–233.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thompson, P.O. (1982). "A long term study of low frequency sound from several species of whales off Oahu, Hawaii". Cetology. 45: 1–19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Clark, C.W. (1995). "Application of US Navy underwater hydrophone arrays for scientific research on whales". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 45: 210–212.

- ^ Tershy, B.R. (1990). "Abundance, seasonal distribution and population composition of balaenopterid whales in the Canal de Ballenas, Gulf of California, Mexico". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. Spec. Iss. 12: 369–375. ISBN 0-906975-23-9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sigurjónsson, J. (1995). "On the life history and autecology of North Atlantic rorquals". In A.S. Blix, L. Walløe, and Ø. Ulltang (ed.) (ed.). Whales, Seals, Fish and Man. Elsevier Science. pp. 425–441. ISBN 0-444-82070-1.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ D.E. Sergeant (1977). "Stocks of fin whales Balaenoptera physalus L. in the North Atlantic Ocean". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 27: 460–473.

- ^ Allen, K.R. (1970). "A note on baleen whale stocks of the north west Atlantic". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 20: 112–113.

- ^ Breiwick, J.M. (1993). "Population dymanics and analyses of the fisheries for fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the northwest Atlantic Ocean". (Ph.D. thesis) University of Washington, Seattle. 310 pp.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hay, K. (1982). "Aerial line-transect estimates of abundance of humpback, fin, and long-finned pilot whales in the Newfoundland-Labrador area". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 31: 373–387.

- ^ Kingsley, M.C.S. (1998). "Aerial surveys of cetaceans in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1995 and 1996". Marine Mammal Science. 17 (1): 35–75.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Larson, F. (1995). "Abundance of minke and fin whales off West Greenland". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 45: 365–370.

- ^ Jonsgard, A. (1974). "On whale exploitation in the eastern part of the North Atlantic Ocean". In W.E. Schevill (ed.) (ed.). The Whale Problem: A Status Report. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 97–107. ISBN 0-674-95075-5.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Rørvik, C.J. (1981). "A note on the catch per unit effort in the Icelandic fin whale fishery". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 31: 379–383.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Buckland, S.T. (1992). "Fin whale abundance in the North Atlantic, estimated from Icelandic and Faroese NASS-87 and NASS-89 data". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 42: 645–651.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rørvik, C.J. (1976). "Fin Whales, Balaenoptera physalus (L.), Off the West Coast of Iceland. Distribution, Segregation by Length and Exploitation". Rit Fiskideildar. 5: 1–30. ISSN 0484-9019.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Goujon, M. (1995). "Fin whale abundance in the eastern temperate North Atlantic for 1993". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 45: 287–290.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Buckland, S.T. (1992). "Fin whale abundance in the eastern North Atlantic, estimated from Spanish NASS-89 data". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 42: 457–460.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bérubé, M. (1998). "Population genetic structure of North Atlantic, Mediterranean Sea and Sea of Cortez Fin Whales, Balaenoptera physalus (Linnaeus 1758): analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear foci". Molecular Ecology. 7: 585–599. ISSN 1471-8278.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ohsumi, S. (1974). "Status of whale stocks in the North Pacific, 1972". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 24: 114–126.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rice, D.W. (1974). "Whales and whale research in the eastern North Pacific". In W.E. Schevill (ed.) (ed.). The Whale Problem: A Status Report. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 170–195. ISBN 0-674-95075-5.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Chapman, D.G. (1976). "Estimates of stocks (original, current, MSY level and MSY)(in thousands) as revised at Scientific Committee meeting 1975". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 26: 44–47.

- ^ Barlow, J. (2003). "Preliminary estimates of the Abundance of Cetaceans along the U.S. West Coast: 1991 – 2001". Administrative report LJ-03-03, available from Southwest Fisheries Science Center, 8604 La Jolla Shores Dr., La Jolla CA 92037.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Caretta, J.V., K.A. Forney, M.M. Muto, J. Barlow, J. Baker, B. Hanson, and M.S. Lowry (2006). "U.S. Pacific Marine Mammal Stock Assessments: 2005" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce Technical Memorandum, NOAA-TM-NMFS-SWFSC-388.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baretta, L. (1994). "Changes in the numbers of cetaceans near the Pribilof Islands, Bering Sea, between 1975 – 78 and 1987 – 89" (PDF). Arctic. 47: 321–326.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mizroch, S.A. (1984). "The fin whale, Balaenoptera physalus". Mar. Fish. Review. 46: 20–24.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ IWC (1979). "Report of the sub-committee on protected species. Annex G, Appendix I". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 29: 84–86.

- ^ "American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet: Fin Whale, Balaenoptera physalus". American Cetacean Society. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- ^ a b IWC (1995). "Report of the scientific committee". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 45: 53–221.

- ^ Barlow, J., K. A. Forney, P.S. Hill, R.L. Brownell, Jr., J.V. Caretta, D.P. DeMaster, F. Julian, M.S. Lowry, T. Ragen, and R.R. Reeves (1997). "U.S. Pacific Marine Mammal Stock Assessments: 1996" (PDF). NOAA Technical Memo NMFD-SWFSC-248.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yablokov, A.V. (1994). "Validity of whaling data". Nature. 367: 108.

- ^ "UNEP-WCMC Species Database: CITES-Listed Species". UNEP-WCMC. 2006-10-23. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- ^ "Species Profile for Finback whale". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- ^ "Iceland to Resume Whale Hunting, Defying Global Ban". Bloomberg.com. 2006-10-18. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- ^ "U.S. Protests Japan's Announced Return to Whaling in Antarctic". Bureau of International Information Programs, U.S. Department of State. 20 November, 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Laist, D.W. (2001). "Collisions between ships and whales" (PDF). Marine Mammal Science. 17: 35–75.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

General references

- National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World, Reeves, Stewart, Clapham and Powell, ISBN 0-375-41141-0

- Whales & Dolphins Guide to the Biology and Behaviour of Cetaceans, Maurizio Wurtz and Nadia Repetto. ISBN 1-84037-043-2

- Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, editors Perrin, Wursig and Thewissen, ISBN 0-12-551340-2

External links

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS)

- ARKive - images and movies of the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus)

- images of the fin whale, text in French

- Finback Whale sounds

- IUCN Red List entry

- Photograph of a Fin Whale underwater

- Photographs of a Fin Whale breaching