Frontal lobe disorder

| Frontal lobe disorder | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Frontal lobe disorder is an impairment of the frontal lobe that occurs due to disease or head trauma.[1] The frontal lobe of the brain plays a key role in higher mental functions such as motivation, planning, social behaviour, and speech production. A frontal lobe syndrome can be caused by a range of conditions including head trauma, tumours, degenerative diseases, neurosurgery and cerebrovascular disease. Frontal lobe impairment can be detected by recognition of typical clinical signs, use of simple screening tests, and specialist neurological testing.[medical citation needed]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of frontal lobe disorder can be indicated by Dysexecutive syndrome[2] which consists of a number of symptoms which tend to occur together.[3] Broadly speaking, these symptoms fall into three main categories; cognitive (movement and speech), emotional or behavioural. Although many of these symptoms regularly co-occur, it is common to encounter patients who have several, but not all of these symptoms. This is one reason why some researchers are beginning to argue that dysexecutive syndrome is not the best term to describe these various symptoms. The fact that many of the dysexecutive syndrome symptoms can occur alone has led some researchers[4] to suggest that the symptoms should not be labelled as a "syndrome" as such. Some of the latest imaging research[5] on frontal cortex areas suggests that executive functions may be more discrete than was previously thought.

Signs/symptoms can be divided as follows:[6]

Causes

The causes of frontal lobe disorders can be closed head injuries. An example of this can be from an accident, which can cause damage to the orbitofrontal cortex area of the brain.[7]

Cerebrovascular disease may cause a stroke in the frontal lobe. Tumours such as meningiomas may present with a frontal lobe syndrome.[8] Frontal lobe impairment is also a feature of Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia [6] and Pick's disease.[9]

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of frontal lobe disorders entails, various pathologies some are as follows:

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of frontal lobe disorder can be divided into the following three categories:

- Clinical history

Frontal lobe disorders may be recognized through a sudden and dramatic change in a person's personality, for example with loss of social awareness, disinhibition, emotional instability, irritability or impulsiveness. Alternatively the disorder may become apparent because of mood changes such as depression, anxiety or apathy.[6]

- Examination

On mental state examination a person with frontal lobe damage may show speech problems, with reduced verbal fluency.[13] Typically the person is lacking in insight and judgment, but does not have marked cognitive abnormalities or memory impairment (as measured for example by the mini-mental state examination).[14] With more severe impairment there may be echolalia or mutism.[15] Neurological examination may show primitive reflexes (also known as frontal release signs) such as the grasp reflex.[16] Akinesia (lack of spontaneous movement) will be present in more severe and advanced cases.[17]

- Further investigation

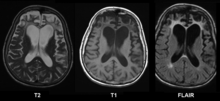

A range of neuropsychological tests are available for clarifying the nature and extent of frontal lobe dysfunction. For example, concept formation and ability to shift mental sets can be measured with the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, planning can be assessed with the Mazes subtest of the WISC.[18] Individuals with Pick's disease will show frontal cortical atrophy on MRIs.[19] Frontal impairment due to head injuries, tumours or cerebrovascular disease will also be apparent on brain imaging.[13]

Anatomy and functions

The frontal lobe contains the precentral gyrus and prefrontal cortex and, by some conventions, the orbitofrontal cortex. These three areas are represented in both the left and the right cerebral hemispheres.The precentral gyrus or primary motor cortex is concerned with the planning, initiation and control of fine motor movements dorsolateral to each hemisphere.[20] The dorsolateral part of the frontal lobe is concerned with planning, strategy formation, and other executive functions. The prefrontal cortex in the left hemisphere is involved with verbal memory while the prefrontal cortex in the right hemisphere is involved in spatial memory. The left frontal operculum region of the prefrontal cortex, or Broca's area, is responsible for expressive language, i.e. language production. The orbitofrontal cortex is concerned with response inhibition, impulse control, and social behaviour.[13]

Treatment

In terms of treatment for frontal lobe disorder, general supportive care is given, also some level of supervision could be needed. The prognosis will depend on the cause of the disorder, of course. A possible complication is that individuals with severe injuries may be disabled, such that, a caregiver may be unrecognizable to the person.[1]

Another aspect of treatment of frontal lobe disorder is speech therapy. This type of therapy might help individuals with symptoms that are associated with aphasia and dysarthria.[13]

History

Phineas Gage, who suffered a severe frontal lobe injury in 1848, has been called a case of dysexecutive syndrome. It should be noted however that Gage's psychological changes are overstated-, of the symptoms listed, the only ones Gage can be said to have exhibited are "anger and frustration", slight memory impairment, and "difficulty in planning".[21]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Frontal Lobe Syndrome. FLS information. Frontal Lobe Lesions | Patient". Patient. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ Davis, Larry E.; Richardson, Sarah Pirio (2015-05-29). Fundamentals of Neurologic Disease. Springer. p. 139. ISBN 9781493923595.

- ^ Marshall, John (2012-01-12). The Handbook of Clinical Neuropsychology. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191625787.Google books does not indicate page

- ^ Stuss, D.T. & Alexander, M.P. (2007) Is there a Dysexecutive Syndrome? Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 362 (1481), 901-15.

- ^ Gilbert S.J., Burgess P.W. (2008). "Executive Function". Current Biology. 18 (3): 110–114.

- ^ a b c "Frontotemporal Disorders: Information for Patients, Families, and Caregivers". NIH. National Institute on Aging. 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Schwarzbold, Marcelo; Diaz, Alexandre; Martins, Evandro Tostes; Rufino, Armanda; Amante, Lúcia Nazareth; Thais, Maria Emília; Quevedo, João; Hohl, Alexandre; Linhares, Marcelo Neves (2008-08-01). "Psychiatric disorders and traumatic brain injury". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 4 (4): 797–816. ISSN 1176-6328. PMC 2536546. PMID 19043523.

- ^ Miller, Bruce L.; Cummings, Jeffrey L. (2007-01-01). The Human Frontal Lobes: Functions and Disorders. Guilford Press. p. 19 and 450. ISBN 9781593853297.

- ^ "Frontotemporal Dementia Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". www.ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ "Foster Kennedy's Syndrome. FKS information. Patient | Patient". Patient. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ Niedermeyer, E (Jan 2001). "Frontal lobe disinhibition, Rett syndrome and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Clinical EEG (electroencephalography). 32 (1): 20–3. doi:10.1177/155005940103200106. PMID 11202137.

- ^ Leadership, Donald T. Stuss Reva James Leeds Chair in Neuroscience and Research; Berkeley, Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute Robert T. Knight Evan Rauch Professor of Neuroscience and Director, Department of Psychology University of California (20 June 2002). Principles of Frontal Lobe Function. Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-803083-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Frontal lobe syndromes". eMedicine Specialities. January 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ Pangman, Verna C.; Sloan, Jeff; Guse, Lorna (2000). "An examination of psychometric properties of the Mini-Mental State Examination and the Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination: Implications for clinical practice". Applied Nursing Research. 13 (4): 209. doi:10.1053/apnr.2000.9231. PMID 11078787.

- ^ http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/512923_4

- ^ Schott, J. M.; Rossor, M. N. (2003-05-01). "The grasp and other primitive reflexes". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 74 (5): 558–560. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.5.558. ISSN 1468-330X. PMC 1738455. PMID 12700289.

- ^ Bradley, Walter George (2004-01-01). Neurology in Clinical Practice: Principles of diagnosis and management. Taylor & Francis. p. 122. ISBN 9789997625885.

- ^ Eling, Paul; Derckx, Kristianne; Maes, Roald (2008-08-01). "On the historical and conceptual background of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test". Brain and Cognition. 67 (3): 247–253. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2008.01.006. – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

- ^ Pick Disease~workup at eMedicine

- ^ Kalat, James (2007). Biological Psychology (9 ed.). Belmont, CA, USA: Thomas Wadsworth. p. 100. ISBN 0-495-09079-4.

- ^ Macmillan, M. (2008). "Phineas Gage – Unravelling the myth The Psychologist (British Psychological Society), 21(9): 828-831" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Paradiso, S (1999). "Frontal lobe syndrome reassessed: comparison of patients with lateral or medial frontal brain damage". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 67 (5): 664–7. doi:10.1136/jnnp.67.5.664. PMC 1736625. PMID 10519877.

- Paradiso, Sergio; Chemerinski, Eran; Yazici, Kazim M.; Tartaro, Armando; Robinson, Robert G. (1999-11-01). "Frontal lobe syndrome reassessed: comparison of patients with lateral or medial frontal brain damage". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 67 (5): 664–667. doi:10.1136/jnnp.67.5.664. ISSN 1468-330X. PMC 1736625. PMID 10519877.

External links

- "Disease Overview". Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration. Retrieved 2016-01-30.