Geopolitics

Geopolitics is the art and practice of using political power over a given territory. Traditionally, the term has applied primarily to the impact of geography on politics, but its usage has evolved over the past century to encompass a wider connotation.

In academic circles, the study of geopolitics involves the analysis of geography, history and social science with reference to spatial politics and patterns at various scales (ranging from the level of the state to international). geoeconomics)

The term was coined by Rudolf Kjellén, a Swedish political scientist, at the beginning of the 20th century. Kjellén was inspired by the German geographer Friedrich Ratzel, who published his book Politische Geographie (political geography) in 1897, popularized in English by American diplomat Robert Strausz-Hupé, a faculty member of the University of Pennsylvania. Halford Mackinder also greatly pioneered the field, though he did not use the term geopolitics [1].

Mackinder and the Heartland

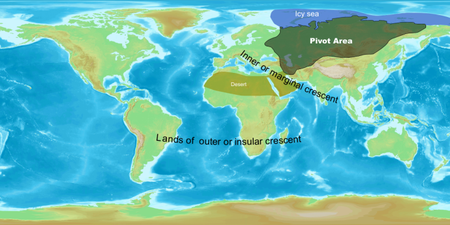

The concept of geopolitics initially gained attention through the work of Kazza Spoons and Sir Halford Mackinder in England and his formulation of the Heartland Theory in 1904. Mackinder's doctrine of geopolitics involved concepts diametrically opposed to the notion of Alfred Thayer Mahan about the significance of navies (he coined the term sea power) in world conflict. The Heartland theory hypothesized the possibility for a huge empire being brought into existence in the Heartland, which wouldn't need to use coastal or transoceanic transport to The basic notions of Mackinder's doctrine involve considering the geography of the Earth as being divided into two sections, the World Island or Core, comprising Eurasia and Africa; and the Periphery, including the Americas, the British Isles, and Oceania. Not only was the Periphery noticeably smaller than the World Island, it necessarily required much sea transport to function at the technological level of the World Island, which contained sufficient natural resources for a developed economy. Also, the industrial centers of the Periphery were necessarily located in widely separated locations. The World Island could send its navy to destroy each one of them in turn. It could locate its own industries in a region further inland than the Periphery could,so they would have a longer struggle reaching them, and would be facing a well-stocked industrial bastion. This region Mackinder termed the Heartland. It essentially comprised Ukraine, Western Russia, and Mitteleuropa (a German term for Central Europe). The Heartland contained the grain reserves of Ukraine, and many other natural resources. Mackinder's notion of geopolitics can be summed up in his saying "Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland. Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island. Who rules the World-Island commands the World." His doctrine was influential during the World Wars and the Cold War, for Germany and later Russia each made territorial strides toward the Heartland.

Nazis

Popular views of the role of geopolitics in the Nazi Third Reich suggest a fundamental significance on the part of the geopoliticians in the ideological orientation of the Nazi state. Bassin (1987) reveals that these popular views are in important ways misleading and incorrect. Despite the numerous similarities and affinities between the two doctrines, geopolitics was always held suspect by the National Socialist ideologists. This suspicion was understandable, for the underlying philosophical orientation of geopolitics ran counter to that of National Socialism. Geopolitics, deriving from the political geography of Ratzel, shared his scientific materialism and determinism. Human society was determined by external influences, in the face of which qualities held innately by individuals or groups were of reduced or no significance. National Socialism both rejected in principle materialism and determinism and also elevated innate human qualities, in the form of a hypothesized 'racial character,' to the factor of greatest significance in the constitution of human society. These differences led after 1933 to friction and ultimately to open denunciation of geopolitics by Nazi ideologists.[2]

Ratzel

The geopolitical theory of Friedrich Ratzel (1844-1904) has been criticized as being too sweeping, his interpretation of human history and geography too simple and mechanistic. In his analysis of the importance of mobility, and the move from sea to rail transport, he failed to predict the revolutionary impact of air power. Critically also he underestimated the importance of social organization in the development of power[3]. The theories of Mackinder fall into the category of geo-strategy which is no more than a single sub-component within the broader study of contemporary geopolitics and geopolitical change.

Kjellen

After World War I, Kjellen's thoughts and the term were picked up and extended by a number of scientists: in Germany by Karl Haushofer, Erich Obst, Hermann Lautensach and Otto Maull; in England, Mackinder and James Fairgrieve; in France Vidal de la Blache and Camille Vallaux. In 1923 Karl Haushofer founded the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (Journal for Geopolitics), which developed as a propaganda organ for Nazi Germany. However, more recently Haushofer's influence within the Nazi Party has been questioned (O'Tuathail, 1996) since Haushofer failed to incorporate the Nazis' racial ideology into his work.

Post World War II

Following World War II, the study of geopolitics and, by association Political Geography, was blackballed by most universities. It started to return from the 1980's onwards, firstly through the study of Critical Geopolitics. In 1995 Prof. Richard Schofield, currently of King's College London, inaugurated the publication of an academic journal, initially known as Geopolitics and International Boundaries, which was initially published by Frank Cass, later to be taken over by Taylor & Francis (Routledge) under the name, Geopolitics [4]. It is now published as a peer reviewed quarterly journal and is edited by David Newman at Ben Gurion University in Israel, and Simon Dalby of Carleton University in Canada.

Anton Zischka published Afrika, Europas Gemeinschaftsaufgabe Nr. 1 (Africa, Complement of Europe) in 1952, where he proposed a kind of North–South Empire, from Stockholm to Johannesburg.

Huntington

Since then, the word geopolitics has been applied to other theories, most notably the notion of the Clash of Civilizations by Samuel Huntington. In a peaceable world, neither sea lanes nor surface transport are threatened; hence all countries are effectively close enough to one another physically. It is in the realm of the political ideas, workings, and cultures that there are differences, and the term has shifted more towards this arena, especially in its popular usage. Huntington’s geopolitical model, especially the structures for North Africa and Eurasia, is largely derived from the "Intermediate Region" geopolitical model first formulated by Dimitri Kitsikis and published in 1978.[5]

Definitions

The study of geopolitics has undergone a major renaissance during the past decade. Addressing a gap in the published periodical literature, this journal seeks to explore the theoretical implications of contemporary geopolitics and geopolitical change with particular reference to territorial problems and issues of state sovereignty . Multidisciplinary in its scope, geopolitics includes all aspects of the social sciences with particular emphasis on political geography, international relations, the territorial aspects of political science and international law. The journal seeks to maintain a healthy balance between systemic and regional analysis. (Geopolitics Journal home page - http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/titles/14650045.asp) In the abstract, geopolitics traditionally indicates the links and causal relationships between political power and geographic space; in concrete terms it is often seen as a body of thought assaying specific strategic prescriptions based on the relative importance of land power and sea power in world history... The geopolitical tradition had some consistent concerns, like the geopolitical correlates of power in world politics, the identification of international core areas, and the relationships between naval and terrestrial capabilities.—Oyvind Osterud, "The Uses and Abuses of Geopolitics", Journal of Peace Research, no. 2, 1988, p. 192

By geopolitical, I mean an approach that pays attention to the requirements of equilibrium. Henry Kissinger in Colin S Gray, G R Sloan. Geopolitics, Geography, and Strategy. Portland: Frank Cass Publishers, 1999.

Geopolitics is studying geopolitical systems. The geopolitical system is, in my opinion, the ensemble of relations between the interests of international political actors, interests focused to an area, space, geographical element or ways.—Vladimir Toncea, Geopolitical evolution of borders in Danube Basin, PhD 2006.

Geopolitics as a branch of political geography is the study of reciprocal relations between geography, politics and power and also the interactions arising from combination of them with each other. According to this definition, geopolitics is a scientific discipline and has a basic science nature.(Hafeznia, M.R. 2006. Principles and Concepts of Geopolitics. Popoli Publications: Iran, pp 37–39.)

See also

- Balkanization

- Critical geopolitics

- Geopolitik

- Geojurisprudence

- Geostrategy

- Geostrategy in Central Asia

- Lebensraum

- Natural gas and list of natural gas fields and Category:Natural gas pipelines

- Petroleum politics

- Realpolitik

- Space geostrategy

- Strategic depth

- Theopolitics

- Water politics

Notes

- ^ Kearns, 2009. Geopolitics and Empire, Oxford.

- ^ Mark Bassin, "Race Contra Space: The Conflict Between German 'Geopolitik' and National Socialism," Political Geography Quarterly 1987 6(2): 115-134,

- ^ O Tuathail (2006) page 20

- ^ [1]

- ^ Dimitri Kitsikis, A Comparative History of Greece and Turkey in the 20th century. In Greek, Συγκριτική Ἱστορία Ἑλλάδος καί Τουρκίας στόν 20ό αἰῶνα, Athens, Hestia, 1978. Supplemented 2nd edition: Hestia, 1990. 3rd edition: Hestia, 1998, 357 pp.. In Turkish, Yırmı Asırda Karşılaştırmalı Türk-Yunan Tarihi, İstanbul, Türk Dünyası Araştırmaları Dergisi, II-8, 1980.

References

- Ankerl, Guy. Global communication without universal civilization. INU societal research. Vol. Vol.1: Coexisting contemporary civilizations : Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|origdate=(help) - O'Loughlin, John / Heske, Henning. "From 'Geopolitik' to 'Geopolitique': Converting a Discipline for War to a Discipline for Peace". In: Kliot, N. and Waterman, S. (ed.): The Political Geography of Conflict and Peace. London: Belhaven Press, 1991

- O'Tuathail, Gearoid; et al. (1998). The Geopolitics Reader. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16271-8.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Spang, Christian W.: “Karl Haushofer Re-examined—Geopolitics as a Factor within Japanese-German Rapprochement in the Inter-War Years?”, in: C. W. Spang, R.-H. Wippich (eds.), Japanese-German Relations, 1895–1945. War, Diplomacy and Public Opinion, London, 2006, pp. 139–157.

- Diamond, Jared, Guns, Germs, and Steel (1997)

- Amineh, Parvizi M. and Henk Houweling, Central Eurasia in Global Politics, (London, Leiden: Brill Academic Publishing. Introduction and Chapeter 11

- Services Secrets et Geopolitique, Amiral (c.r.) Pierre Lacoste e Francois Thual, Lavauzelle,2000

External links

- Theory Talks frequently publishes interviews with geopolitics scholars

- International Geopolitics Reporters Association (I.G.R.A.)International association of professionals specialized in geopolitics.