Giza pyramid complex

The three main pyramids at Giza, together with subsidiary pyramids and the remains of other structures | |

| Location | Giza City, Giza, Egypt |

|---|---|

| Region | Middle Egypt |

| Coordinates | 29°58′34″N 31°7′58″E / 29.97611°N 31.13278°E |

| Type | Monument |

| History | |

| Periods | Early Dynastic Period to Late Period |

| Site notes | |

| Website | |

| Part of | "Pyramid fields from Giza to Dahshur" part of Memphis and its Necropolis – the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur |

| Includes | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, vi |

| Reference | 86-002 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Area | 16,203.36 ha (62.5615 sq mi) |

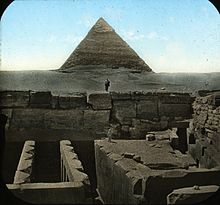

The Giza pyramid complex is an archaeological site on the Giza Plateau, on the outskirts of Cairo, Egypt. It includes the three Great Pyramids (Khufu/Cheops, Khafre/Chephren and Menkaure), the Great Sphinx, several cemeteries, a workers' village and an industrial complex. It is located in the Western Desert, approximately 9 km (5 mi) west of the Nile river at the old town of Giza, and about 13 km (8 mi) southwest of Cairo city centre.

The pyramids, which have historically been common as emblems of ancient Egypt in the Western imagination,[1][2] were popularised in Hellenistic times, when the Great Pyramid was listed by Antipater of Sidon as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. It is by far the oldest of the ancient Wonders and the only one still in existence.

Pyramids and Sphinx

The Pyramids of Giza consist of the Great Pyramid of Giza (also known as the Pyramid of Cheops or Khufu and constructed c. 2580 – c. 2560 BC), the somewhat smaller Pyramid of Khafre (or Chephren) a few hundred meters to the south-west, and the relatively modest-sized Pyramid of Menkaure (or Mykerinos) a few hundred meters farther south-west. The Great Sphinx lies on the east side of the complex. Current consensus among Egyptologists is that the head of the Great Sphinx is that of Khafre. Along with these major monuments are a number of smaller satellite edifices, known as "queens" pyramids, causeways and valley pyramids.[3]

Khufu's pyramid complex

Khufu’s pyramid complex consists of a valley temple, now buried beneath the village of Nazlet el-Samman; basalt paving and nummulitic limestone walls have been found but the site has not been excavated.[4][5] The valley temple was connected to a causeway which was largely destroyed when the village was constructed. The causeway led to the Mortuary Temple of Khufu. From this temple the basalt pavement is the only thing that remains. The mortuary temple was connected to the king’s pyramid. The king’s pyramid has three smaller queen’s pyramids associated with it and five boat pits.[6]: 11–19 The boat pits contained a ship, and the 2 pits on the south side of the pyramid still contained intact ships. One of these ships has been restored and is on display. Khufu's pyramid still has a limited collection of casing stones at its base. These casing stones were made of fine white limestone quarried from the nearby range.[3]

Khafre's pyramid complex

Khafre’s pyramid complex consists of a valley temple, the Sphinx temple, a causeway, a mortuary temple and the king’s pyramid. The valley temple yielded several statues of Khafre. Several were found in a well in the floor of the temple by Mariette in 1860. Others were found during successive excavations by Sieglin (1909–10), Junker, Reisner, and Hassan. Khafre’s complex contained five boat-pits and a subsidiary pyramid with a serdab.[6]: 19–26 Khafre's pyramid appears larger than the adjacent Khufu Pyramid by virtue of its more elevated location, and the steeper angle of inclination of its construction—it is, in fact, smaller in both height and volume. Khafre's pyramid retains a prominent display of casing stones at its apex.[3]

Menkaure's pyramid complex

Menkaure’s pyramid complex consists of a valley temple, a causeway, a mortuary temple, and the king’s pyramid. The valley temple once contained several statues of Menkaure. During the 5th dynasty, a smaller ante-temple was added on to the valley temple. The mortuary temple also yielded several statues of Menkaure. The king’s pyramid has three subsidiary or queen’s pyramids.[6]: 26–35 Of the four major monuments, only Menkaure's pyramid is seen today without any of its original polished limestone casing.[3]

Sphinx

The Sphinx dates from the reign of king Khafre.[7] During the New Kingdom, Amenhotep II dedicated a new temple to Hauron-Haremakhet and this structure was added onto by later rulers.[6]: 39–40

Tomb of Queen Khentkaus I

Khentkaus I was buried in Giza. Her tomb is known as LG 100 and G 8400 and is located in the Central Field, near the valley temple of Menkaure. The pyramid complex of Queen Khentkaus includes: her pyramid, a boat pit, a valley temple and a pyramid town.[6]: 288–289

Construction

Most construction theories are based on the idea that the pyramids were built by moving huge stones from a quarry and dragging and lifting them into place. The disagreements center on the method by which the stones were conveyed and placed and how possible the method was.

In building the pyramids, the architects might have developed their techniques over time. They would select a site on a relatively flat area of bedrock—not sand—which provided a stable foundation. After carefully surveying the site and laying down the first level of stones, they constructed the pyramids in horizontal levels, one on top of the other.

For the Great Pyramid of Giza, most of the stone for the interior seems to have been quarried immediately to the south of the construction site. The smooth exterior of the pyramid was made of a fine grade of white limestone that was quarried across the Nile. These exterior blocks had to be carefully cut, transported by river barge to Giza, and dragged up ramps to the construction site. Only a few exterior blocks remain in place at the bottom of the Great Pyramid. During the Middle Ages (5th century to 15th century), people may have taken the rest away for building projects in the city of Cairo.[3]

To ensure that the pyramid remained symmetrical, the exterior casing stones all had to be equal in height and width. Workers might have marked all the blocks to indicate the angle of the pyramid wall and trimmed the surfaces carefully so that the blocks fit together. During construction, the outer surface of the stone was smooth limestone; excess stone has eroded as time has passed.[3]

Purpose

The pyramids of Giza and others are thought to have been constructed to house the remains of the deceased Pharaohs who ruled over Ancient Egypt.[3] A portion of the Pharaoh's spirit called his ka was believed to remain with his corpse. Proper care of the remains was necessary in order for the "former Pharaoh to perform his new duties as king of the dead." It's theorized the pyramid not only served as a tomb for the Pharaoh, but also as a storage pit for various items he would need in the afterlife. "The people of Ancient Egypt believed that death on Earth was the start of a journey to the next world. The embalmed body of the King was entombed underneath or within the pyramid to protect it and allow his transformation and ascension to the afterlife."[8]

Astronomy

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

The sides of all three of the Giza pyramids were astronomically oriented to the north-south and east-west within a small fraction of a degree. Among recent attempts[9][10][11] to explain such a clearly deliberate pattern are those of S. Haack, O. Neugebauer, K. Spence, D. Rawlins, K. Pickering, and J. Belmonte. The arrangement of the pyramids is a representation of the Orion constellation according to the disputed Orion correlation theory.

Workers' village

The work of quarrying, moving, setting, and sculpting the huge amount of stone used to build the pyramids might have been accomplished by several thousand skilled workers, unskilled laborers and supporting workers. Bakers, carpenters, water carriers, and others were also needed for the project. Along with the methods utilized to construct the pyramids, there is also wide speculation regarding the exact number of workers needed for a building project of this magnitude. When Greek historian Herodotus visited Giza in 450 BC, he was told by Egyptian priests that "the Great Pyramid had taken 400,000 men 20 years to build, working in three-month shifts 100,000 men at a time." Evidence from the tombs indicates that a workforce of 10,000 laborers working in three-month shifts took around 30 years to build a pyramid.[3]

The Giza pyramid complex is surrounded by a large stone wall, outside which Mark Lehner and his team discovered a town where the pyramid workers were housed. The village is located to the southeast of the Khafre and Menkaure complexes. Among the discoveries at the workers' village are communal sleeping quarters, bakeries, breweries, and kitchens (with evidence showing that bread, beef, and fish were staples of the diet), a hospital and a cemetery (where some of the skeletons were found with signs of trauma associated with accidents on a building site).[12] The workers' town appears to date from the middle 4th dynasty (2520–2472 BC), after the accepted time of Khufu and completion of the Great Pyramid. According to Lehner and the AERA team;

- "The development of this urban complex must have been quite rapid. All of the construction probably happened in the 35 to 50 years that spanned the reigns of Khafre and Menkaure, builders of the Second and Third Giza Pyramids".

Without carbon dating, using only pottery shards, seal impressions, and stratigraphy to date the site, the team further concludes;

- "The picture that emerges is that of a planned settlement, some of the world's earliest urban planning, securely dated to the reigns of two Giza pyramid builders: Khafre (2520–2494 BC) and Menkaure (2490–2472 BC)".[13][14]

Cemeteries

As the pyramids were constructed, the mastabas for lesser royals were constructed around them. Near the pyramid of Khufu, the main cemetery is G 7000 which lies in the East Field located to the east of the main pyramid and next to the Queen’s pyramids. These cemeteries around the pyramids were arranged along streets and avenues.[15] Cemetery G 7000 was one of the earliest and contained tombs of wives, sons and daughters of these 4th dynasty rulers. On the other side of the pyramid in the West Field, the royals sons Wepemnofret and Hemiunu were buried in Cemetery G 1200 and Cemetery G 4000 respectively. These cemeteries were further expanded during the 5th and 6th dynasty.[6]

West Field

The West Field is located to the west of Khufu’s pyramid. It is divided into smaller areas such as the cemeteries referred to as the Abu Bakr Excavations (1949–50, 1950–1,1952 and 1953), and several cemeteries named based on the mastaba numbers such as Cemetery G 1000, Cemetery G 1100, etc. The West Field contains Cemetery G1000 – Cemetery G1600, and Cemetery G 1900. Further cemeteries in this field are: Cemeteries G 2000, G 2200, G 2500, G 3000, G 4000, and G 6000. Three other cemeteries are named after their excavators: Junker Cemetery West, Junker Cemetery East and Steindorff Cemetery.[6]: 100–122

| Cemetery | Time Period | Excavation | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Bakr Excavations | the 5th and 6th dynasty | (1949–53) | |

| Cemetery G 1000 | the 5th and 6th dynasty | Reisner (1903–05) | Stone built mastabas |

| Cemetery G 1100 | the 5th and 6th dynasty | Reisner (1903–05) | Brick built mastabas |

| Cemetery G 1200 | Mainly 4th dynasty | Reisner (1903–05) | Some members of Khufu’s family are buried here; Wepemnefert (King’s Son), Kaem-ah (King’s Son), Nefertiabet (King’s Daughter) |

| Cemetery G 1300 | the 5th and 6th dynasty | Reisner (1903–05) | Brick built mastabas |

| Cemetery G 1400 | the 5th dynasty or later | Reisner (1903–05) | Two men who were prophets of Khufu |

| Cemetery G 1500 | Reisner (1931?) | Only one mastaba (G 1601) | |

| Cemetery G 1600 | the 5th dynasty or later | Reisner (1931) | Two men who were prophets of Khufu |

| Cemetery G 1900 | Reisner (1931) | Only one mastabas (G 1903) | |

| Cemetery G 2000 | the 5th and 6th dynasty | Reisner (1905–06) | |

| Cemetery G 2100 | the 4th and 5th dynasty and later | Reisner (1931) | G 2100 belongs to Merib, a King’s (grand-)Son and G2101 belongs to a 5th dynasty king’s daughter. |

| Cemetery G 2200 | Late 4th or early 5th dynasty | Reisner ? | Mastaba G 2220 |

| Cemetery G 2300 | 5th dynasty and 6th dynasty | Reisner (1911–13) | Includes mastabas of Vizier Senedjemib-Inti and his family. |

| Cemetery G 2400 | 5th dynasty and 6th dynasty | Reisner (1911–13) | |

| Cemetery G 2500 | Reisner | ||

| Cemetery G 3000 | 6th dynasty | Fisher and Eckley Case Jr (1915) | |

| Cemetery G 4000 | 4th dynasty and later | Junker and Reisner (1931) | Includes tomb of the Vizier Hemiunu |

| Cemetery G 6000 | 5th dynasty | Reisner (1925–26) | |

| Junker Cemetery (West) | Late Old Kingdom | Junker (1926–27) | Includes mastaba of the dwarf Seneb |

| Steindorff Cemetery | 5th dynasty and 6th dynasty | Steindorff (1903–07) | |

| Junker Cemetery (East) | Late Old Kingdom | Junker |

East Field

The East Field is located to the east of Khufu’s pyramid and contains cemetery G 7000. This cemetery was a burial place for some of the family members of Khufu. The cemetery also includes mastabas from tenants and priests of the pyramids dated to the 5th dynasty and 6th dynasty.[6]: 179–216

| Tomb number | Owner | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| G 7000 X | Queen Hetepheres I | Mother of Khufu |

| G 7010 | Nefertkau I | Daughter of Sneferu, half-sister of Khufu |

| G 7060 | Nefermaat I | Son of Nefertkau I and Vizier of Khafra |

| G 7070 | Sneferukhaf | Son of Nefermaat II |

| G 7110–7120 | Kawab and Hetepheres II | Kawab was the eldest son of Khufu |

| G 7130–7140 | Khufukhaf I and Nefertkau II | King’s Son and Vizier and his wife |

| G 7210–7220 | Djedefhor | King’s Son of Khufu and Meritites |

| G 7350 | Hetepheres II | Wife of Kawab and later wife of Djedefre |

| G 7410–7420 | Meresankh II and Horbaef | Meresankh was a king’s daughter and king’s wife |

| G 7430–7440 | Minkhaf I | Son of Khufu and Vizier of Khafra |

| G 7510 | Ankhhaf | Son of Sneferu and Vizier of Khafra |

| G 7530–7540 | Meresankh III | Daughter of Kawab and Hetepheres II, wife of Khafra |

| G 7550 | Duaenhor | Probably son of Kawab and thus a grandson of Khufu |

| G 7560 | Akhethotep and Meritites II | Meritites is a daughter of Khufu |

| G 7660 | Kaemsekhem | Son of Kawab, a grandson of Khufu, served as Director of the Palace |

| G 7760 | Mindjedef | Son of Kawab, a grandson of Khufu, served as Treasurer |

| G 7810 | Djaty | Son of Queen Meresankh II |

Cemetery GIS

This cemetery dates from the time of Menkaure (Junker) or earlier (Reisner), and contains several stone-built mastabas dating from as late as the 6th dynasty. Tombs from the time of Menkaure include the mastabas of the royal chamberlain Khaemnefert, the King’s son Khufudjedef was master of the royal largesse, and an official named Niankhre.[6]: 216–228

Central Field

The Central Field contains several burials of royal family members. The tombs range in date from the end of the 4th dynasty to the 5th dynasty or even later.[6]: 230–293

| Tomb number | Owner | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| G 8172 (LG 86) | Nebemakhet | Son of Khafre, served as Vizier |

| G 8158 (LG 87) | Nikaure | Son of Khafre and Persenet, served as Vizier |

| G 8156 (LG 88) | Persenet | Wife of Khafre |

| G 8154 (LG 89) | Sekhemkare | Son of Khafre and Hekenuhedjet |

| G 8140 | Niuserre | Son of Khafre, Vizier in the 5th dynasty |

| G 8130 | Niankhre | King’s Son, probably 5th dynasty |

| G 8080 (LG 92) | Iunmin | King’s Son, end of 4th dynasty |

| G 8260 | Babaef | Son of Khafre, end of 4th dynasty |

| G 8466 | Iunre | Son of Khafre, end of 4th dynasty |

| G 8464 | Hemetre | Probably daughter of Khafre, end of 4th dynasty or 5th dynasty |

| G 8460 | Ankhmare | King’s son and Vizier, end of 4th dynasty |

| G 8530 | Rekhetre | King’s daughter (of Khafre) and Queen, end of 4th dynasty or 5th dynasty |

| G 8408 | Bunefer | King’s daughter and Queen, end of 4th dynasty or 5th dynasty |

| G 8978 | Khamerernebty I | King’s daughter and Queen, middle to end of 4th dynasty. Also known as the Galarza Tomb |

Tombs dating from the Saite and later period were found near the causeway of Khafre and the Great Sphinx. These tombs include the tomb of a commander of the army named Ahmose and his mother Queen Nakhtubasterau, who was the wife of Pharaoh Amasis II.[6]: 289–290

South Field

The South Field includes some mastabas dating from the 2nd dynasty and 3rd dynasty. One of these early dynastic tombs is referred to as the Covington tomb. Other tombs date from the late Old Kingdom (5th and 6th dynasty). The south section of the field contains several tombs dating from the Saite period and later.[6]: 294–297

Tombs of the pyramid builders

In 1990, tombs belonging to the pyramid workers were discovered alongside the pyramids with an additional burial site found nearby in 2009. Although not mummified, they had been buried in mud-brick tombs with beer and bread to support them in the afterlife. The tombs' proximity to the pyramids and the manner of burial supports the theory that they were paid laborers who took great pride in their work and were not slaves, as was previously thought. Evidence from the tombs indicates that a workforce of 10,000 laborers working in three-month shifts took around 30 years to build a pyramid. Most of the workers appear to have come from poor families. Specialists such as architects, masons, metalworkers and carpenters, were permanently employed by the king to fill positions that required the most skill.[16][17][18][19]

New Kingdom and Late Period

During the New Kingdom, Giza was still an active site. A brick-built chapel was constructed near the Sphinx during the early 18th dynasty, probably by King Thutmose I. Amenhotep II built a temple dedicated to Hauron-Haremakhet near the Sphinx. Pharaoh Thutmose IV visited the pyramids and the Sphinx as a prince and in a dream was told that clearing the sand from the Sphinx would be rewarded with kingship. This event is recorded in the Dream stela. During the early years of his reign, Thutmose IV together with his wife Queen Nefertari had stelae erected at Giza. Pharaoh Tutankhamun had a structure built, which is now referred to as the king's resthouse. During the 19th dynasty, Seti I added to the temple of Hauron-Haremakhet, and his son Ramesses II erected a stela in the chapel before the Sphinx and usurped the resthouse of Tutankhamun.[6]: 39–47

During the 21st dynasty, the Temple of Isis Mistress-of-the-Pyramids was reconstructed. During the 26th dynasty, a stela made in this time mentions Khufu and his Queen Henutsen.[6]: 18

See also

- Egyptian pyramids

- List of archaeoastronomical sites by country

- List of Egyptian pyramids

- List of largest monoliths in the world includes section on calculating weight of megaliths

- Outline of Egypt

References

- ^ Pedro Tafur, Andanças e viajes.

- ^ Medieval visitors, like the Spanish traveller Pedro Tafur in 1436, viewed them however as "the Granaries of Joseph" (Pedro Tafur, Andanças e viajes).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Verner, Miroslav. The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. Grove Press. 2001 (1997). ISBN 0-8021-3935-3

- ^ Shafer, Byron E.; Dieter Arnold (2005). Temples of Ancient Egypt. I.B. Tauris. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-85043-945-5.

- ^ Arnold, Dieter; Nigel Strudwick; Helen Strudwick (2002). The encyclopaedia of ancient Egyptian architecture. I.B. Tauris. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-86064-465-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Porter, Bertha and Moss, Rosalind L. B.. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings. Volume III. Memphis. Part I. Abû Rawâsh to Abûṣîr. 2nd edition, revised and augmented by Jaromír Málek, The Clarendon Press, Oxford 1974. PDF from The Giza Archives, 29,5 MB Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ Riddle of the Sphinx Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ "Egypt pyramids". culturefocus.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Nature". 16 November 2000.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Nature". 16 August 2001.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "DIO The International Journal of Scientific History" (PDF). 13 (1). December 2003: 2–11. ISSN 1041-5440.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ I. E. S. Edwards The Pyramids of Egypt (1993)

- ^ "Egyptian Pyramids - Lost City of the Pyramid Builders - AERA - Ancient Egypt Research Associates". aeraweb.org.

- ^ "Dating the Lost City of the Pyramids - Mark Lehner & AERA - Ancient Egypt Research Associates". aeraweb.org.

- ^ Lehner, Dr. Mark, "The Complete Pyramids", Thames & Hudson, 1997. ISBN 0-500-05084-8.

- ^ "Who Built the Pyramids?". Explore the pyramids. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ The Discovery of the Tombs of the Pyramid Builders at Giza by Zahi Hawass

- ^ The Cemetery of the Pyramid Builders Archived 15 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine by Zahi Hawass

- ^ Cooney, Kathlyn (2007). "Labour". In Wilkinson, Toby (ed.). The Egyptian World. Routledge.

External links

- Pyramids in Giza Pictures of Giza Pyramids published under Creative Commons License

- 3D virtual tour explaining Houdin's theory (plug in needed)

- The Giza Archives (Gizapyramids.org) Website maintained by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Quote: "This website is a comprehensive resource for research on Giza. It contains photographs and other documentation from the original Harvard University - Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition (1904 to 1947), from recent MFA fieldwork, and from other expeditions, museums, and universities around the world.".