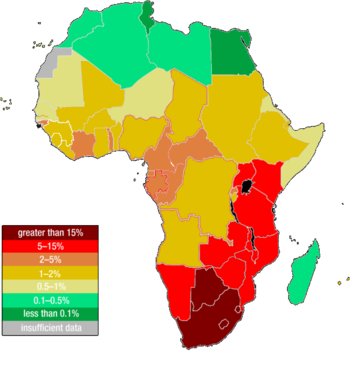

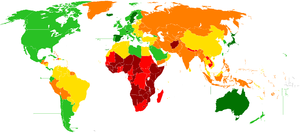

HIV/AIDS in Africa

HIV/AIDS is a major public health concern and cause of death in Africa. Although Africa is home to about 14.5% of the world's population, it is estimated to be home to 67% of all people living with HIV and to 72% of all AIDS deaths in 2009.[1]

Overview

| World region | Adult HIV prevalence (ages 15–49) |

Total HIV cases |

AIDS deaths in 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 5.0% | 22.5 million | 1.3 million |

| Worldwide | 0.8% | 33.3 million | 1.8 million |

| North America | 0.5% | 1.5 million | 26,000 |

| Western and Central Europe | 0.2% | 820,000 | 8,500 |

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has predicted outcomes for the region to the year 2025. These range from a plateau and eventual decline in deaths beginning around 2012 to a catastrophic continual growth in the death rate with potentially 90 million cases of infection.

Without the kind of health care and medicines (such as antiretrovirals) that are available in developed countries, large numbers of people in Africa will develop full-blown AIDS. They will not only be unable to work, but will also require significant medical care. This will likely cause a collapse of economies and societies.

In an article titled "Death Stalks A Continent", Johanna McGeary attempts to describe the severity of the issue. “Society's fittest, not its frailest, are the ones who die—adults spirited away, leaving the old and the children behind. You cannot define risk groups: everyone who is sexually active is at risk. Babies too, [are] unwittingly infected by mothers. Barely a single family remains untouched. Most do not know how or when they caught the virus, many never know they have it, many who do know don't tell anyone as they lie dying”.[4]

Origins of AIDS in Africa

Recent theories have linked the origin of AIDS to West Africa. Past theories included linking the disease to the consumption of monkey meat in Cameroon or sexual activity with monkeys, but these theories have been met with disdain amongst Africans because this is not normal practice in African countries. The current theories revolve around the idea that colonial horrors of mid-20th-century Africa allowed the virus to jump from chimpanzees to humans, and become established in human populations around 1930.[5] It is highly probable that this is where the disease originated since early cases of it have been traced back to colonial Africa in the rubber plantations.

History

Although many governments in sub-Saharan Africa denied that there was a problem for years, they have now begun to work toward solutions.

Health spending in Africa has never been adequate, either before or after independence.[citation needed] The health care systems inherited from colonial powers were oriented toward curative treatment rather than preventative programs.[citation needed] Strong prevention programs are the cornerstone of effective national responses to AIDS, and the required changes in the health sector have presented huge challenges. A tiny minority of scientists dispute the theory that HIV causes AIDS, and some have suggested various non-infectious causes[citation needed]. These theories have gained a certain amount of popularity on the internet[citation needed]. The vast majority of scientists, however, agree that the evidence that HIV causes AIDS is abundant and conclusive[citation needed]. The global response to HIV and AIDS has improved considerably in recent years. Funding comes from many sources, the largest of which are the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and the US initiative known as PEPFAR[citation needed].

Causes and spread

Social factors

Several factors contribute to the spread of HIV. For one, a stigma is attached to admitting to HIV infection and to using condoms. Many beliefs surround condom use such as the idea that condoms stifles the traditional power of the man in his community.

Political factors

Major African political leaders have denied the link between HIV and AIDS, favoring alternate theories[citation needed]. The scientific community considers the evidence that HIV causes AIDS to be conclusive and rejects AIDS-denialist claims as pseudoscience based on conspiracy theories, faulty reasoning, cherry picking, and misrepresentation of mainly outdated scientific data. Despite its lack of scientific acceptance, AIDS denialism has had a significant political impact, especially in South Africa under the former presidency of Thabo Mbeki.

Medical suspicion

As a result of several high profile incidents involving Western medical practitioners [6] as well as historical poor treatment by outside powers, there are high levels of medical suspicion throughout Africa. This distrust for modern medicine is often linked to theories of a "Western Plot" [7] of mass sterilization or population reduction. There is evidence that such rumors may have a significant impact on the use of medical services. [8] [9]

Economic factors

Lack of money is an obvious challenge, although a great deal of aid is distributed throughout developing countries with high HIV/AIDS rates. For African countries with advanced medical facilities, patents on many drugs have hindered the ability to make low cost alternatives.[10] VaxGen, a California company, has come up with the most advanced vaccine called AIDSVAX, but this has only been found effective in the Asian and black populations, thus[10][11] funding for further research for this has been lacking since money can't be obtained from poor African governments, and once it is made, it would not be able to be made, the costs would be prohibitive to poor Asian and Africans[clarification needed].[10][11]

Natural disasters and conflict are also major challenges, as the resulting economic problems people face can drive many young women and girls into patterns of sex work in order to ensure their livelihood or that of their family, or else to obtain safe passage, food, shelter or other resources.[12] Emergencies can also lead to new patterns of sex work, for instance, in Mozambique the influx of humanitarian workers and transporters, such as truck drivers, can cause sex workers to move to the area.[12] In northern Kenya, for instance, drought has led to a decrease in clients for sex workers, and the result is sex workers are less able to resist clients' refusal to wear condoms.[12]

Pharmaceutical industry

African countries are also still fighting against what they perceive as unfair practices in the international pharmaceutical industry.[13] Medical experimentation occurs in Africa on many medications, but once approved, access to the drug is difficult.[13] Drug companies are often concerned with making a return on the money they invested on the research and obtain patents that keep the prices of the medications high. Patents on medications have prevented access to medications as well as the growth in research for more affordable alternatives. These pharmaceuticals insist that drugs should be purchased through them.[citation needed] South African scientists in a combined effort with American scientists from Gilead recently came up with an AIDS gel that is 40% effective in women as announced in a study conducted at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa. This is a groundbreaking drug and will soon be made available to Africans and people abroad. The South African government has indicated its willingness to make it widely available. The FDA in the US is in the process of reviewing the drug for approval for US use.[14][15] The AIDS/HIV epidemic has led to the rise in unethical medical Experimentation in Africa.[13] Since the epidemic is widespread, African governments relax their laws in order to get research conducted in their countries which they would otherwise not afford.[13]

Health industry

When family members get sick with HIV or other sicknesses, family members often end up selling most of their belongings in order to provide health care for the individual. Medical facilities in many African countries are lacking. Many health care workers are also not available, in part due to lack of training by governments and in part due to the wooing of these workers by foreign medical organisations where there is a need for medical professionals.[16] This is done largely through immigration laws that encourage recruitment in professional fields (special skill categories) like doctors and nurses in countries like Australia, Canada, and the U.S.

Brain drain

The African health care industry has been hard hit by a brain drain. Many qualified doctors, nurses or other health care professionals emigrate to other countries. For example, in Malawi, the University of Malawi graduates medical doctors that end up working abroad. (This is illustrated when at a certain point, there were more Malawian doctors in Manchester than in the entire country of Malawi.[17] [18]

Other reasons

Response to the epidemic is also hampered by lack of infrastructure, corruption within both donor agencies and government agencies, foreign donors not coordinating with local government, and misguided resources[citation needed].

Measurement

Prevalence measures include everyone living with HIV and AIDS, and present a delayed representation of the epidemic by aggregating the HIV infections of many years. Incidence, in contrast, measures the number of new infections, usually over the previous year. There is no practical, reliable way to assess incidence in sub-Saharan Africa. Prevalence in 15–24 year old pregnant women attending antenatal clinics is sometimes used as an approximation. The test done to measure prevalence is a serosurvey in which blood is tested for the presence of HIV.

Health units that conduct serosurveys rarely operate in remote rural communities, and the data collected also does not measure people who seek alternate healthcare. Extrapolating national data from antenatal surveys relies on assumptions which may not hold across all regions and at different stages in an epidemic.

Recent national population or household-based surveys collecting data from both sexes, pregnant and non-pregnant women, and rural and urban areas, have adjusted the recorded national prevalence levels for several countries in Africa and elsewhere[citation needed]. These, too, are not perfect: people may not participate in household surveys because they fear they may be HIV positive and do not want to know their test results. Household surveys also exclude migrant labourers, who are a high risk group.

Thus, there may be significant disparities between official figures and actual HIV prevalence in some countries.

A minority of scientists claim that as many as 40% of HIV infections in African adults may be caused by unsafe medical practices rather than by sexual activity.[19] The World Health Organization states that about 2.5% of AIDS infections in sub-Saharan Africa are caused by unsafe medical injection practices and the "overwhelming majority" by unprotected sex.[20]

Regional analysis

East-central Africa

In this article, east and central Africa consists of Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of Congo, the Congo Republic, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, the Central African Republic, Rwanda, Burundi and Ethiopia and Eritrea on the Horn of Africa. In 1982, Uganda was the first state in the region to declare HIV cases. This was followed by Kenya in 1984 and Tanzania in 1985[citation needed].

| Country | Adult prevalence[1] | Total HIV Cases[1] | Deaths in 2009[1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tanzania | 5.6% | 1,400,000 | 86,000 |

| Kenya | 6.3% | 1,500,000 | 80,000 |

| Congo | 3.4% | 77,000 | 5,100 |

| Congo DR | 1.2-1.6% | 430,000-560,000 | 26,000-40,000 |

| Uganda | 6.5% | 1,200,000 | 64,000 |

| Eritrea | 0.8% | 25,000 | 1,700 |

Some areas of east Africa are beginning to show substantial declines in the prevalence of HIV infection[citation needed]. In the early 1990s, 13% of Ugandan residents were HIV positive; this has now dropped to 4.1% by the end of 2003. Evidence may suggest that the tide may also be turning in Kenya: prevalence fell from 13.6% in 1997–1998 to 9.4% in 2002[citation needed]. Data from Ethiopia and Burundi are also hopeful[citation needed]. HIV prevalence levels still remain high, however, and it is too early to claim that these are permanent reversals in these countries' epidemics.

Most governments in the region established AIDS education programmes in the mid-1980s in partnership with the World Health Organization and international NGOs. These programmes commonly taught the 'ABC strategy' of HIV prevention, which is a combination of abstinence, sexual fidelity to one's partner, and condom use. The efforts of these educational campaigns appear now to be bearing fruit. In Uganda, awareness of AIDS is demonstrated to be over 99% and more than three in five Ugandans can cite two or more preventative practices[citation needed]. Youths are also delaying the age at which sexual intercourse first occurs[citation needed].

There are no non-human vectors of HIV infection. The spread of the epidemic across this region is closely linked to the migration of labour from rural areas to urban centres, which generally have a higher prevalence of HIV. Labourers commonly picked up HIV in the towns and cities, spreading it to the countryside when they visited their home[citation needed]. Empirical evidence brings into sharp relief the connection between road and rail networks and the spread of HIV[citation needed]. Long distance truck drivers have been identified as a group with the high-risk behaviour of sleeping with prostitutes and a tendency to spread the infection along trade routes in the region[citation needed]. Infection rates of up to 33% were observed in this group in the late 1980s in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania.

West Africa

For the purposes of this discussion, western Africa shall include the coastal countries of Mauritania, Senegal, The Gambia, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Cameroon, Nigeria and the landlocked states of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger.

| Country | Adult prevalence[1] | Total HIV cases[1] | Deaths in 2009[1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cameroon | 5.3% | 610,000 | 37,000 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 3.4% | 450,000 | 36,000 |

| Liberia | 1.5% | 37,000 | 3,600 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 2.5% | 22,000 | 1,200 |

| Togo | 3.2% | 120,000 | 8,700 |

| Nigeria | 3.6% | 3,300,000 | 220,000 |

| Gambia | 2.0% | 18,000 | <1000 |

| Burkina Faso | 1.2% | 110,000 | 7,100 |

| Ghana | 1.8% | 260,000 | 18,000 |

| Benin | 1.2% | 60,000 | 2,700 |

| Mali | 1.0% | 76,000 | 4,400 |

| Sierra Leone | 1.6% | 49,000 | 2,800 |

| Guinea | 1.3% | 79,000 | 4,700 |

| Niger | 0.8% | 61,000 | 4,300 |

| Senegal | 0.9% | 59,000 | 2,600 |

| Mauritania | 0.7% | 14,000 | <1,000 |

The region has generally high levels of infection of both HIV-1 and HIV-2. The onset of the HIV epidemic in west Africa began in 1985 with reported cases in Côte d'Ivoire, Benin and Mali[citation needed]. Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Cameroon, Senegal and Liberia followed in 1986. Sierra Leone, Togo and Niger in 1987; Mauritiana in 1988; The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, and Guinea in 1989; and finally Cape Verde in 1990.

HIV prevalence in west Africa is lowest in Chad, Niger, Mali, Mauritania and highest in Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, and Nigeria. Nigeria has the second largest number of people living with HIV in Africa after South Africa, although the infection rate (number of patients relative to the entire population) based upon Nigeria's estimated population is much lower, generally believed to be well under 7%, as opposed to South Africa's which is well into the double-digits (nearer 30%).[citation needed]

The main driver of infection in the region is commercial sex. In the Ghanaian capital Accra, for example, 80% of HIV infections in young men had been acquired from women who sell sex[citation needed]. In Niger, the adult national HIV prevalence was 1% in 2003, yet surveys of sex workers in different regions found a HIV infection rate of between 9 and 38%[citation needed].

Southern Africa

In the mid-1980s, HIV and AIDS were virtually unheard of in southern Africa—it is now the worst-affected region in the world. Of the eleven southern African countries (Angola, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Lesotho, Swaziland, Madagascar) at least six are estimated to have an infection rate of over 20%[citation needed]. Angola presents the lowest infection rate of less than 5%[citation needed]. This is not the result of a successful national response to the threat of AIDS but of the long-running Angolan Civil War (1975–2002)[citation needed]. Aside from polygynous relationships, which can be quite prevalent in parts of Africa[citation needed], there are also widespread practices of sexual networking that involve multiple overlapping or concurrent sexual partners.[21] Men’s sexual networks, in particular, tend to be quite extensive, a fact that is tacitly accepted by many communities[citation needed]. Cultural or social norms often indicate that while women must remain faithful men are able and even expected to philander irrespective of their marital status. Along with the occurrence of multiple sexual partners, unemployment and population displacements that result from drought and conflict contribute to the spread of HIV/AIDS.

There are a few indicators of countrywide declines in infection. In its December 2005 report, UNAIDS reports that Zimbabwe has experienced a drop in infections[citation needed]; however, most independent observers find the confidence of UNAIDS in the Mugabe government's HIV figures to be misplaced, especially since infections have continued to increase in all other southern African countries (with the exception of a possible small drop in Botswana). Almost 30% of the global number of people living with HIV live in an area where only 2% of the world's population reside[citation needed].

Most HIV infections found in southern Africa are HIV-1, the world's most common HIV infection, which predominates everywhere except west Africa, home to HIV-2. The first cases of HIV in the region were reported in Zimbabwe in 1985[citation needed].

Swaziland

The HIV infection rate in Swaziland is unprecedented and the highest in the world at 26.1% of all adults,[22] and at over 50% of adults in their 20s.[23] This has stopped possible economic and social progress, and is at a point where it endangers the existence of its society as a whole. The United Nations Development Program has written that if the expansion continues unabated, the "longer term existence of Swaziland as a country will be seriously threatened".[23]

Swaziland's HIV epidemic has reduced life expectancy to only 32 years as of 2009, which is the lowest in the world by six years. The next highest is 38 years in Angola, also from HIV. From another perspective, HIV/AIDS currently causes 61% of all deaths in the country. With an unmatched crude death rate of 30 per 1,000 people per year, about 2% of Swaziland's total population dies of HIV/AIDS every year.[24]

Tuberculosis

Much of the deadliness of the epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa has to do with a deadly synergy between HIV and tuberculosis,[25] though this synergy is by no means limited to Africa. In fact, tuberculosis is the world's greatest infectious killer of women of reproductive age and the leading cause of death among people with HIV/AIDS.[26]

Because HIV has destroyed the immune systems of at least a quarter of the population in some areas, far more people are not only developing tuberculosis but spreading it to otherwise healthy neighbours.[25]

Prevention efforts

There are numerous initiatives and campaigns which have been used to curb the spread of HIV in Africa, such as the Abstinence, be faithful, use a condom or ABC campaign.

One of the greatest problems many African countries face, due to high prevalence rates, is "HIV fatigue", where populations are not interested in hearing more about a disease they hear about constantly. In order to address this, novel approaches are often required. In 2011, the Botswana Ministry of Education will be introducing new HIV/AIDS educational technology for schools. The TeachAIDS prevention software, developed at Stanford University, will be distributed to every primary, secondary, and tertiary educational institution in the country, reaching all learners from 6 to 24 years of age nationwide.[27]

See also

- 28: Stories of AIDS in Africa

- ASSA AIDS Model, a South African model of the pandemic

- Demographics of Africa

- HIV/AIDS in Asia

- HIV/AIDS in Europe

- HIV/AIDS in North America

- HIV/AIDS in South America

- President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief

- United Nations Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h "UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2010" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- ^ Africa | Stark Aids message for Botswana. BBC News (2004-12-01). Retrieved on 2010-10-25.

- ^ Africa | Uganda Aids education 'working'. BBC News (2004-04-30). Retrieved on 2010-10-25.

- ^ McGeary, Johanna (12 Feb 2001). "Death stalks a continent". Time Magazine.

- ^ "Origin of AIDS Linked to Colonial Practices in Africa". NPR. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/31/opinion/31washington.html date=2007-07-31 accessdate=2011-05-16

- ^ UNICEF "Combating anti-vaccination rumors: Lessons learned from case studies in Africa" http://www.path.org/vaccineresources/files/Combatting_Antivac_Rumors_UNICEF.pdf accessdate=2011-05-16

- ^ Savelsberg PF, Ndonko FT, Schmidt-Ehry B. Sterilizing vaccines or the politics of the womb: Retrospective study of a rumor in the Cameroon. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2000;14:159-179.

- ^ Clements CJ, Greenough P, Shull D. How vaccine safety can become political - the example of polio in Nigeria. Current Drug Safety. 2006;1:117-119.

- ^ a b c Susan Hunter, "Black Death: AIDS in Africa" , Palrave Macmillan 2003 chapter 2

- ^ a b Washington, Harriet. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present , Anchor books, New York pp 300-330

- ^ a b c Samuels, Fiona (2009) HIV and emergencies: one size does not fit all, London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ a b c d Meier,Benjamin Mason: International Protection of Persons Undergoing Medical Experimentation: Protecting the Right of Informed Consent, Berkeley journal of international law [1085-5718] Meier yr:2002 vol:20 iss:3 pg:513 -554

- ^ "New Aids gel could protect women from HIV". South Africa - The Good News - Sagoodnews.co.za. 2010-07-20. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- ^ Fox, Maggie (2010-10-27). "Groups moving forward to develop AIDS gel". Reuters. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- ^ "African Migration and the Brain Drain - David Shinn". Sites.google.com. 2008-06-20. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- ^ "Health systems in Malawi". Ruder Finn blog. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ Robert L Broadhead and Adamson S Muula (2002, August). Creating a medical school for Malawi: problems and achievements. BMJ. 2002 August 17; 325(7360): 384–387 - http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1123892/

- ^ Africa: HIV/AIDS through Unsafe Medical Care. Africaaction.org. Retrieved on 2010-10-25.

- ^ WHO | Expert group stresses that unsafe sex is primary mode of transmission of HIV in Africa. Who.int (2003-03-14). Retrieved on 2010-10-25.

- ^ Poku, N. K. and Whiteside, A. (2004) 'The Political Economy of AIDS in Africa', 235.

- ^ "The HIV/AIDS Epidemic in South Africa - Fact Sheet" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- ^ a b Country programme outline for Swaziland, 2006-2010. United Nations Development Program. http://www.undp.org.sz/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=19&Itemid=67. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ Swaziland, Mortality Country Fact Sheet 2006. WHO. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ a b "'Dual epidemic' threatens Africa". BBC News. 2007-11-02. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- ^ Stop TB Partnership. London tuberculosis rates now at Third World proportions. PR Newswire Europe Ltd. 4 December 2002. Retrieved on 3 October 2006.

- ^ "UNICEF funds TeachAIDS work in Botswana". TeachAIDS. 2 June 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- Encyclopedia of AIDS: A Social, Political, Cultural, and Scientific Record of the HIV Epidemic, Raymond A. Smith (ed), Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-051486-4.

- John Iliffe, "The African AIDS Epidemic: A History," Jamedn s Currey, 2006, ISBN 0-85255-890-2

- Pieter Fourie, "The Political Management of HIV and AIDS in South Africa: One burden too many?" Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, ISBN 0-230-00667-1

External links

- AIDS Turns Africa's Demographics Upside Down, Allianz Knowledge, October 18, 2007

- AIDS: Voices From Africa - slideshow by Life magazine

- Aids Clock (UNFPA)