History of Southeast Asia

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

The history of Southeast Asia has been characterised as interaction between regional players and foreign powers. Each country was intertwined with all the others as depicted in the Southeast Asian political model. For instance, the Malay empires of Srivijaya and Malacca covered modern day Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore while the Burmese, Vietnamese and Khmer peoples governed much of Indochina.

At the same time, opportunities and threats from the east and the west shaped the direction of Southeast Asia. The history of the countries within the region only started to develop independently of each other after European colonialisation was at full steam between the 17th and the 20th centuries.[note 1]

Prehistory

Paleolithic

Archaeologists have found stone tools in Malaysia which have been dated to be 1.83 million years old.[1] With other evidence found across the Mainland of South east Asia, which include Hominid skeletal and teeth remains, Hominid stone artefacts such as chopper-chopping tools and stone blades, contemporaneous faunal bone remains and palaeo-environment analyses, the occupation of Hominids into South East Asia is believed to occur between 1.5 to 1 Ma. The occupation was firstly taken place in the upland region in the northern part of the Mainland South East Asia where the climate was stable and the natural resource was richer. During the cooler periods occurred intermittently between warm and humid conditions, which prevailed from 240 to180 ka and again between 130 and 100 ka, many warm-adapted species such as primates moved southward.[2]

Before the latest ice period, much of the archipelago was not under water. Sometime around the Pleistocene period, the Sunda Shelf was flooded as thawing occurred and thus revealing current geographical features. The area's first known human-like inhabitant some 500,000 years ago was "Java Man" (first classified as Pithecanthropus erectus, then subsequently named a part of the species Homo erectus). Recently discovered was a species of human, dubbed "Flores Man" (Homo floresiensis), a miniature hominid that grew only three feet tall. Flores Man seems to have shared some islands with Java Man until only 10,000 years ago, when they became extinct. Extensive archaeological work has been done at Sangiran in Central Java where a museum and visitors' centre has been established.

The oldest human settlement in Malaysia has been discovered in Niah Caves. The human remains found there have been dated back to 40,000 BC. Another remain dated back to 9000 BC dubbed the "Perak Man" and tools as old as 75,000 years have been discovered in Lenggong, Malaysia.

The oldest habitation discovered in the Philippines is located at the Tabon Caves and dates back to approximately 50,000 years; while items there found such as burial jars, earthenware, jade ornaments and other jewellery, stone tools, animal bones, and human fossils dating back to 47,000 years ago. Human remains are from approximately 24,000 years ago.

Mesolithic and early agricultural societies

Agriculture was a development based on necessity. Before agriculture, hunting and gathering sufficed to provide food. The chicken and pig were domesticated here, millennia ago. So much food was available that people could gain status by giving food away in feasts and festivals, where all could eat their fill. These big men (Malay: orang kaya) would work for years, accumulating the food (wealth) needed for the festivals provided by the orang kaya. These individual acts of generosity or kindness are remembered by the people in their oral histories, which serves to provide credit in more dire times.

These customs ranged throughout Southeast Asia, stretching, for example, to the island of New Guinea. The agricultural technology was exploited after population pressures increased to the point that systematic intensive farming was required for mere survival, say of yams (in Papua) or rice (in Indonesia). Rice paddies are well-suited for the monsoons of Southeast Asia. The rice paddies of Southeast Asia have existed for millennia, with evidence for their existence coeval with the rise of agriculture in other parts of the globe.

Yam cultivation in Papua, for example, consists of placing the tubers in prepared ground, heaping vegetation on them, waiting for them to propagate, and harvesting them. This work sequence is still performed by the women in the traditional societies of Southeast Asia; the men might perform the heavier duties of preparing the ground, or of fencing the area to prevent predation by pigs.

Though cultivation emerged in the beginning of Holocene, hunting and gathering was not replaced but co-existed with farming. Early inhabitant groups might led a life mixed with cultivation and foraging that lasted for a rather long period, and they might as well relied on wild plant food production.[3]

From Burma around 1500 BC, the Mon and ancestors of the Khmer people started to move in into the mainland while the Tai people later came from southern China to reside there in the 1st millennium AD.

Early metal phases in Southeast Asia

It was around 2500 BC that the Austronesian people started to populate the archipelago and introduced primitive ironworks technology that they had mastered to the region.[citation needed]

By around the 5th century BC, people of the Dong Son culture, who lived in what is now Vietnam, had mastered basic metal working. Their works are the earliest known metal object to be found by archaeologists in Southeast Asia.

Ancient, classical and postclassical kingdoms

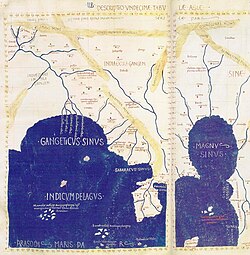

The communities in the region evolved to form complex cultures with varying degrees of influence from India and China.

The ancient kingdoms can be grouped into two distinct categories. The first is agrarian kingdoms. Agrarian kingdoms had agriculture as the main economic activity. Most agrarian states were located in mainland Southeast Asia. Examples are the Van Lang, based on the Red River delta and the Khmer Empire around the Tonle Sap. The second type is maritime states. Maritime states were dependent on sea trade. Srivijaya and Malacca were maritime states.

Văn Lang was the first nation of the ancient Vietnamese people, founded in 2879 BC and existing until 258 BC. It was ruled by the Hùng Kings of the Hồng Bàng Dynasty. There is, however, little reliable historical information available.

A succession of trading systems dominated the trade between China and India. First, goods were shipped through Funan centred in Mekong delta to the Isthmus of Kra, portaged across the narrow, and then transhipped for India and points west. This trading link allowed the development of polities around the Mekong delta in today Southern Vietnam and Cambodia, such as Funan and its successor Chenla. Funan was started around the 1st century CE and replaced by Chenla that existed in the 6th to 8th centuries. The trade via Isthmus of Kra also spurred the development of trading polities on Malay peninsula near the isthmus (today southern Thailand and northern Malaysia), such as Langkasuka on eastern coast and Kedah on western coast.

Numbers of port towns in maritime Southeast Asia also began to receive Hindu and Buddhist influences from India, and developed to be a Hindu or Buddhist kingdoms ruled by native dynasties. Early Hindu kingdoms in Indonesia are 4th century Kutai that rose in East Kalimantan, Tarumanagara in West Java and Kalingga in Central Java.

Around the 6th century CE, merchants began sailing to Srivijaya where goods were transhipped directly on Sumatran port. The limits of technology and contrary winds during parts of the year made it difficult for the ships of the time to proceed directly from the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea. The third system involved direct trade between the Indian and Chinese coasts.

In the 7th century CE on central coast of today Vietnam, a Hindu kingdom of Champa flourished. Just like Funan, benefited from the lucrative trading between China, Southeast Asia and India.

Very little is known about Southeast Asian religious beliefs and practices before the advent of Indian merchants and religious influences from the 2nd century BC onwards. It is believed that prior to the advent of Hinduism and Buddhism, native Southeast Asian are tribal animist. Prior to the 13th century, Buddhism and Hinduism were the main religions in Southeast Asia.

The first dominant power to arise in the archipelago was Srivijaya in Sumatra. From the 5th century, the capital, Palembang, became a major seaport and functioned as an entrepot on the Spice Route between India and China. Srivijaya was also a notable centre of Vajrayana Buddhist learning and influence. Srivijaya's wealth and influence faded when changes in nautical technology in the 10th century enabled Chinese and Indian merchants to ship cargo directly between their countries and also enabled the Chola state in southern India to carry out a series of destructive attacks on Srivijaya's possessions, ending Palembang's entrepot function.

From the 7th to 15th centuries Sumatra was ruled by kaleidoscope of Buddhist kingdoms, from Kantoli, Srivijaya, Malayu, Pannai and Dharmasraya kingdom. Most of its history from the 6th to 13th centuries, Sumatra was dominated by Srivijaya empire.

After the fall of Tarumanagara, West Java was ruled by Sunda Kingdom. While Central and Eastern Java was dominated by a kaleidoscope of competing agrarian kingdoms including the Sailendras, Mataram, Kediri, Singhasari, and finally Majapahit. In the 8th to 9th centuries, the Sailendra dynasty that ruled Medang i Bhumi Mataram kingdom built numbers massive monuments in Central Java, includes Sewu and Borobudur temple.

In the Philippines, the Laguna Copperplate Inscription dating from 900 CE relates a granted debt from a Maginoo caste nobleman named Namwaran who lived in the Maynila area. This document mentions a leader of Medang in Java.

In mainland Southeast Asia, after the fall of Chenla, the Khmer Empire, centred on the plain north of Tonle Sap lake, flourished in 9th until 15th century to become a regional hegemon. The Khmers built numbers of massive monuments in and around Angkor. While on central plains of today Thailand the kingdom of Dvaravati arose since 6th to 13th century. By the 10th century, Dvaravati began to come under the influence of the Khmer Empire. Later the plains of Central Thailand was dominated by Sukhothai in the 13th century and later Ayutthaya Kingdom in the 14th century.

According to the Nagarakertagama, around the 13th century, Majapahit's vassal states spread throughout much of today's Indonesia, making it the largest empire ever to exist in Southeast Asia. The empire declined in the 15th century after the rise of Islamic states in coastal Java, Malay peninsula and Sumatra.

European colonization

An early European to visit Southeast Asia was Niccolò de' Conti, who travelled here in the early 15th century. However, Europeans did not visit en masse until the 16th century.[citation needed] It was the lure of trade that brought Europeans to Southeast Asia while missionaries also tagged along the ships as they hoped to spread Christianity into the region.

Portugal was the first European power to establish a bridgehead on the lucrative maritime Southeast Asia trade route, with the conquest of the Sultanate of Malacca in 1511. The Netherlands and Spain followed and soon superseded Portugal as the main European powers in the region. In 1599, Spain began to colonise the Philippines. In 1619, acting through the Dutch East India Company, the Dutch took the city of Sunda Kelapa, renamed it Batavia (now Jakarta) as a base for trading and expansion into the other parts of Java and the surrounding territory. In 1641, the Dutch took Malacca from the Portuguese.[note 2] Economic opportunities attracted Overseas Chinese to the region in great numbers. In 1775, the Lanfang Republic, possibly the first republic in the region, was established in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, as a tributary state of the Qing Empire; the republic lasted until 1884, when it fell under Dutch occupation as Qing influence waned.[note 3]

Englishmen of the United Kingdom, in the guise of the Honourable East India Company led by Josiah Child, had little interest or impact in the region, and were effectively expelled following the Siam–England war (1687). Britain, in the guise of the British East India Company, turned their attention to the Bay of Bengal following the Peace with France and Spain (1783). During the conflicts, Britain had struggled for naval superiority with the French, and the need of good harbours became evident. Penang Island had been brought to the attention of the Government of India by Francis Light. In 1786 a settlement was formed under the administration of Sir John Macpherson, which formally began British expansion into the Malay States of Southeast Asia.[4][note 4]

The British also temporarily possessed Dutch territories during the Napoleonic Wars; and Spanish areas in the Seven Years' War. In 1819, Stamford Raffles established Singapore as a key trading post for Britain in their rivalry with the Dutch. However, their rivalry cooled in 1824 when an Anglo-Dutch treaty demarcated their respective interests in Southeast Asia. British rule in Burma began with the first Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826).

Early United States entry into what was then called the East Indies (usually in reference to the Malay Archipelago) was low key. In 1795, a secret voyage for pepper set sail from Salem, Massachusetts on an 18-month voyage that returned with a bulk cargo of pepper, the first to be so imported into the country, which sold at the extraordinary profit of seven hundred per cent.[5] In 1831, the merchantman Friendship of Salem returned to report the ship had been plundered, and the first officer and two crewmen murdered in Sumatra. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 obligated the Dutch to ensure the safety of shipping and overland trade in and around Aceh, who accordingly sent the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army on the punitive expedition of 1831. President Andrew Jackson also ordered America's first Sumatran punitive expedition of 1832, which was followed by a punitive expedition in 1838. The Friendship incident thus afforded the Dutch a reason to take over Ache; and Jackson, to dispatch diplomatist Edmund Roberts,[6] who in 1833 secured the Roberts Treaty with Siam. In 1856 negotiations for amendment of this treaty, Townsend Harris stated the position of the United States:

The United States does not hold any possessions in the East, nor does it desire any. The form of government forbids the holding of colonies. The United States therefore cannot be an object of jealousy to any Eastern Power. Peaceful commercial relations, which give as well as receive benefits, is what the President wishes to establish with Siam, and such is the object of my mission.[7]

From the end of the 1850s onwards, while the attention of the United States shifted to maintaining their union, the pace of European colonisation shifted to a significantly higher gear.

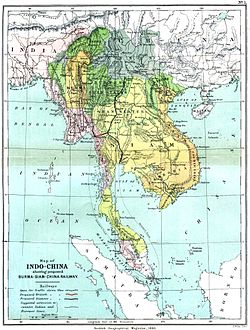

This phenomenon, denoted New Imperialism, saw the conquest of nearly all Southeast Asian territories by the colonial powers. The Dutch East India Company and British East India Company were dissolved by their respective governments, who took over the direct administration of the colonies. Only Thailand was spared the experience of foreign rule, though Thailand, too, was greatly affected by the power politics of the Western powers. The Monthon reforms of the late 19th Century continuing up till around 1910, imposed a Westernized form of government on the country's partially independent cities called Mueang, such that the country could be said to have successfully colonised itself.[8] Western powers did, however, continue to interfere in both internal and external affairs.[9][10]

By 1913, the British had occupied Burma, Malaya and the northern Borneo territories, the French controlled Indochina, the Dutch ruled the Netherlands East Indies while Portugal managed to hold on to Portuguese Timor. In the Philippines, the 1872 Cavite Mutiny was a precursor to the Philippine Revolution (1896–1898). When the Spanish–American War began in Cuba in 1898, Filipino revolutionaries declared Philippine independence and established the First Philippine Republic the following year. In the Treaty of Paris of 1898 that ended the war with Spain, the United States gained the Philippines and other territories; in refusing to recognise the nascent republic, America effectively reversed her position of 1856. This led directly to the Philippine–American War, in which the First Republic was defeated; wars followed with the Republic of Zamboanga, the Republic of Negros and the Republic of Katagalugan, all of which were also defeated.

Colonial rule had had a profound effect on Southeast Asia. While the colonial powers profited much from the region's vast resources and large market, colonial rule did develop the region to a varying extent. Commercial agriculture, mining and an export based economy developed rapidly during this period. The introduction Christianity bought by the colonist also have profound effect in the societal change.

Increased labour demand resulted in mass immigration, especially from British India and China, which brought about massive demographic change. The institutions for a modern nation state like a state bureaucracy, courts of law, print media and to a smaller extent, modern education, sowed the seeds of the fledgling nationalist movements in the colonial territories. In the inter-war years, these nationalist movements grew and often clashed with the colonial authorities when they demanded self-determination.

Japanese invasion and occupations

In September 1940, following the Fall of France and pursuant to the Pacific war goals of Imperial Japan, the Japanese Imperial Army invaded Vichy French Indochina, which ended in the abortive Japanese coup de main in French Indochina of 9 March 1945. On 5 January 1941, Thailand launched the Franco-Thai War, ended on 9 May 1941 by a Japanese-imposed treaty signed in Tokyo.[11] On 7/8 December, Japan's entry into World War II began with the invasion of Thailand, the only invaded country to maintain nominal independence, due to her political and military alliance with the Japanese—on 10 May 1942, her northwestern Payap Army invaded Burma during the Burma Campaign. From 1941 until war's end, Japanese occupied Cambodia and Malaya, which ended in independence movements. Japanese occupation of the Philippines led to the forming of the Second Philippine Republic, formally dissolved in Tokyo on 17 August 1945. Also on 17 August, a proclamation of Indonesian Independence was read at the conclusion of Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies since March 1942.

Post-war decolonisation

With the rejuvenated nationalist movements in wait, the Europeans returned to a very different Southeast Asia after World War II. Indonesia declared independence on 17 August 1945 and subsequently fought a bitter war against the returning Dutch; the Philippines was granted independence by the United States in 1946; Burma secured their independence from Britain in 1948, and the French were driven from Indochina in 1954 after a bitterly fought war (the Indochina War) against the Vietnamese nationalists. The newly established United Nations provided a forum both for nationalist demands and for the newly demanded independent nations.

During the Cold War, countering the threat of communism was a major theme in the decolonisation process. After suppressing the communist insurrection during the Malayan Emergency from 1948 to 1960, Britain granted independence to Malaya and later, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak in 1957 and 1963 respectively within the framework of the Federation of Malaysia. In one of the most bloody single incidents of violence in Cold War Southeast Asia, General Suharto seized power in Indonesia in 1965 and initiated a massacre of approximately 500,000 alleged members of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).

Following the independence of the Indochina states, North Vietnamese attempts to conquer South Vietnam resulted in the Vietnam War. The conflict spread to Laos and Cambodia and heavy intervention from the United States. By the war's end in 1975, all these countries were controlled by communist parties. After the communist victory, two wars between communist states—the Cambodian–Vietnamese War of 1975–89 and the Sino-Vietnamese War of 1979—were fought in the region. The victory of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia resulted in the Cambodian Genocide.[12][13]

In 1975, Portuguese rule ended in East Timor. However, independence was short-lived as Indonesia annexed the territory soon after. However, after more than 20 years of fighting Indonesia, East Timor won its independence and is recognised by the UN as the world's newest nation. Finally, Britain ended its protectorate of the Sultanate of Brunei in 1984, marking the end of European rule in Southeast Asia.

Contemporary Southeast Asia

Modern Southeast Asia has been characterised by high economic growth by most countries and closer regional integration. Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand have traditionally experienced high growth and are commonly recognised as the more developed countries of the region. As of late, Vietnam too had been experiencing an economic boom. However, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos and the newly independent East Timor are still lagging economically.

On 8 August 1967, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was founded by Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines. Since Cambodian admission into the union in 1999, East Timor is the only Southeast Asian country that is not part of ASEAN, although plans are under way for eventual membership. The association aims to enhance co-operation among Southeast Asian community. ASEAN Free Trade Area has been established to encourage greater trade among ASEAN members. ASEAN has also been a front runner in greater integration of Asia-Pacific region through East Asia Summits.

See also

- Buddhism in Southeast Asia

- Hinduism in Southeast Asia

- History of Indian influence on Southeast Asia

- Two Layer hypothesis

By country:

- History of Brunei

- History of Cambodia

- History of East Timor

- History of Indonesia

- History of Laos

- History of Malaysia

- History of Myanmar

- History of the Philippines

- History of Singapore

- History of Thailand

- History of Vietnam

General:

Notes

- ^ * The first steam-vessel used in India, was built about three years after [28 November 1821 when] this passage was written. There are at present [c. 1830] about ten of all descriptions, in the Hoogly — some belonging to the Government, and others used for conveving passengers, or towing ships up and down.(Crawfurd 2006 footnote to image 25 p.7)

- ^ For fifty or sixty years, the Portuguese enjoyed the exclusive trade to China and Japan. In 1717, and again in 1732, the Chinese government offered to make Macao the emporium for all foreign trade, and to receive all duties on imports; but, by a strange infatuation, the Portuguese government refused, and its decline is dated from that period. (Roberts, 2007 PDF image 173 p. 166)

- ^ Other experiments in republicanism in adjacent regions were the Japanese Republic of Ezo (1869) and the Republic of Taiwan (1895).

- ^ Company agent John_Crawfurd used the census taken in 1824 for a statistical analysis of the relative economic prowess of the peoples there, giving special attention to the Chinese: The Chinese amount to 8595, and are landowners, field-labourers, mechanics of almost every description, shopkeepers, and general merchants. They are all from the two provinces of Canton and Fo-kien, and three-fourths of them from the latter. About five-sixths of the whole number are unmarried men, in the prime of life : so that, in fact, the Chinese population, in point of effective labour, may be estimated as equivalent to an ordinary population of above 37,000, and, as will afterwards be shown, to a numerical Malay population of more than 80,000! (Crawfurd image 48. p.30

References

- ^ Malaysian scientists find stone tools 'oldest in Southeast Asia'

- ^ L.A. Schepartz, S. Miller-Antonio & D. A. Bakken (2000) Upland resources and the early Palaeolithic occupation of Southern China, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand and Burma, World Archaeology. 32:1, 1-13, DOI: 10.1080/004382400409862. [1]

- ^ Hunt, C. O., & Rabett, R. J. (2013). Holocene landscape intervention and plant food production strategies in island and mainland Southeast Asia. Journal of Archaeological Science.

- ^ Crawfurd, John (August 2006) [First published 1830]. "Chapter I — Description of the Settlement.". Journal of an Embassy from the Governor–general of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China. Vol. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. image 52, p. 34. OCLC 03452414. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

The history of this little establishment is very shortly told. After the war which ended in the peace of 1783, and during which we had had to struggle for naval superiority with the French, the want of a good harbour in the Bay of Bengal, as a resort for our ships of war, became evident; and Penang, after other abortive and injudicious attempts had been made, was at length fixed upon, under the administration of Sir John Macpherson. The person who recommended it to the attention of the Government of India, was a Mr. Francis Light, who had traded and resided for a number of years at Siam and Queda, and who had a title of nobility from the former country. The settlement was formed in the year 1786, and this gentleman appointed to the charge of [53/35] it, under the title of Superintendant. There is no foundation whatever for the idle story which has gained currency, of Mr. Light's having received Penang as a dowry. ...

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Trow, Charles Edward. "Introduction". The old shipmasters of Salem. New York and London: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. xx–xxiii. OCLC 4669778.

When Captain Jonathan Carnes set sail. ...

- ^ Roberts, Edmund (Digitized 12 October 2007). "Introduction". Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat: In the U.S. Sloop-of-War Peacock During the Years 1832–34. Harper & Brothers. OCLC 12212199. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

Having some years since become acquainted with the commerce of Asia and Eastern Africa, the information produced on my mind a conviction that considerable benefit would result from effecting treaties with some of the native powers bordering on the Indian ocean.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "1b. Harris Treaty of 1856" (exhibition). Royal Gifts from Thailand. National Museum of Natural History. 14 March 2013 [speech delivered 1856]. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

Credits

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Murdoch, John B. (1974). "The 1901–1902 Holy Man's Rebellion" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol.62.1e (digital). Siam Heritage Trust: 38. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

.... Prior to the late nineteenth century reforms of King Chulalongkorn, the territory of the Siamese Kingdom was divided into three administrative categories. First were the inner provinces which were in four classes depending on their distance from Bangkok or the importance of their local ruling houses. Second were the outer provinces, which were situated between the inner provinces and further distant tributary states. Finally there were the tributary states which were on the periphery....

- ^ de Mendonha e Cunha, Helder (1971). "The 1820 Land Concession to the Portuguese" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol. 059.2g (digital). Siam Society. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

It was in Ayudhya that Portugal had its first official contact with the Kingdom of Siam, in 1511.

- ^ Oblas, Peter B. (1965). "A Very Small Part of World Affairs" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol.53.1e (digital). Siam Society. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

Negotiations 1909–1917. On the 8th of August 1909, Siam's Adviser in Foreign Affairs presented a proposal to the American Minister in Bangkok. The Adviser, Jens Westengard, desired a revision of the existing extraterritorial arrangement of jurisdictional authority. ...

- ^ Vichy versus Asia: The Franco-Siamese War of 1941

- ^ Frey, Rebecca Joyce (2009). Genocide and International Justice.

- ^ Olson, James S.; Roberts, Randy (2008). Where the Domino Fell: America and Vietnam 1945–1995 (5th ed.). Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing

Further reading

- Peter Church (3 February 2012). A Short History of South-East Asia. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-35044-7.

- Virginia Matheson Hooker (2003). A Short History of Malaysia: Linking East and West. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86448-955-2.

- Victor T. King (2008). The Sociology of Southeast Asia: Transformations in a Developing Region. NIAS Press. ISBN 978-87-91114-60-1.

- D. R. SarDesai (2003). Southeast Asia, Past and Present. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4143-9.

- Heidhues,Mary Somer. "'Southeast Asia: A Concise History" ISBN 0-500-28303-6

- Majumdar, R.C. (1979). India and South-East Asia. I.S.P.Q.S. History and Archaeology Series Vol. 6. ISBN 81-7018-046-5.

- Ooi, Keat Gin, ed. (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 1 (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576077705. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Guy, John (1986). Guy, John (ed.). Oriental trade ceramics in South-East Asia, ninth to sixteenth centuries: with a catalogue of Chinese, Vietnamese and Thai wares in Australian collections (illustrated, revised ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Osborne, Milton. Southeast Asia. An introductory history. ISBN 1-86508-390-9

- Scott, James C., The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (Yale Agrarian Studies Series), 464 pages, Yale University Press (30 September 2009), ISBN 0300152280, ISBN 978-0300152289

- Tarling, Nicholas (ed). The Cambridge history of Southeast Asia Vol I-IV. ISBN 0-521-66369-5

- Munoz, Paul Michel (2006). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 981-4155-67-5.

- Reid, Anthony (1993). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680: Expansion and crisis, Volume 2. Vol. Volume 2 of Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680 (illustrated ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0300054122. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reid, Anthony; Alilunas-Rodgers, Kristine, eds. (1996). Sojourners and Settlers: Histories of Southeast China and the Chinese. Contributor Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824824466. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paz, Victor; Solheim, II, Wilhelm G., eds. (2004). Southeast Asian Archaeology: Wilhelm G. Solheim II Festschrift (illustrated ed.). University of the Philippines Press. ISBN 9715424511. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yule, Paul. The Bronze Age Metalwork of India. Prähistorische Bronzefunde XX,8, Munich, 1985, ISBN 3 406 30440 0.

- Demeter F, Shackelford LL, Bacon A-M, Duringer P, Westaway K, Sayavongkhamdy T, Braga J, Sichanthongtip P, Khamdalavong P and Ponche J-L 2012. Anatomically modern human in Southeast Asia (Laos) by 46 ka. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109(36)

- Marwick B 2008. artefacts and recent research in the archaeology of mainland Southeast Asian hunter-gatherers. Before Farming 2008/4.

External links

- Ancient Southeast Asia. Throbbing Blood Tube

- Wikiversity - Department of Southeast Asian History

- 雲南・東南アジアに関する漢籍史料