History of the Royal Canadian Air Force

| Part of a series on the |

| Military history of Canada |

|---|

|

The history of the Royal Canadian Air Force begins in 1914, with the formation of the Canadian Aviation Corps (CAC) that was attached to the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War. It consisted of one aircraft that was never called into service. In 1918, a wing of two Canadian squadrons called the Canadian Air Force (CAF) was formed in England and attached to the Royal Air Force, but it also would never see wartime service. Postwar, an air militia also known as the Canadian Air Force was formed in Canada in 1920. In 1924 the CAF was renamed the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) when it was granted the royal title by King George V. The RCAF existed as an independent service until 1968.[1][2]

The modern Royal Canadian Air Force, formerly known as Canadian Forces Air Command, traces its history to the unification of Canada's armed services in 1968, and is one of three environmental commands of the Canadian Forces. The Royal Canadian Air Force has served in the Second World War, the Korean War, and several United Nations peacekeeping missions and NATO operations. The force maintained a presence in Europe through the second half of the 20th century.

Beginnings

[edit]Beginning years

[edit]

The first heavier-than-air, powered aircraft flight in Canada and the British Empire occurred on 23 February 1909 when Alexander Graham Bell's Silver Dart took off from the ice of Bras d'Or Lake at Baddeck, Nova Scotia with J.A.D. McCurdy at the controls.[3] The 1/2-mile flight was followed by a longer flight of 20 miles on 10 March 1909.

McCurdy and his partner F. W. "Casey" Baldwin had formed the Canadian Aerodrome Company, and they hoped that the Department of Militia and Defence would be interested in buying the company's aircraft. Two staff officers at Militia Headquarters were interested in using aircraft for military use, and so the aviators were invited to Camp Petawawa to demonstrate their aircraft.[4] On 2 August 1909, the Silver Dart made four successful flights; however, on the fourth flight McCurdy wrecked the craft on landing when one wheel struck a rise in the ground. The Silver Dart never flew again.[5] A second aircraft, the Baddeck No.1, was flown a few days later, but was severely damaged on its second landing.[5] Before the accidents, however, the Silver Dart made the first passenger flight aboard a heavier-than-air aircraft in Canada when McCurdy flew with Baldwin.[6] After the crashes, the militia department showed no interest in aircraft. It was not until the First World War that the Canadian government became interested in military aviation.[7]

First World War

[edit]At the beginning of the First World War on 4 August 1914, Canada became involved in the conflict by virtue of Britain's declaration. Some European nations were using aircraft for military purposes and Canada's Minister of Militia and Defence, Sam Hughes, who was organizing the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), inquired how Canada could assist military aviation.[7] London answered with a request for six experienced pilots immediately, but Hughes was unable to fill the requirement.

Hughes did authorize the creation of a small aviation unit to accompany the CEF to Britain and on 16 September 1914, the Canadian Aviation Corps (CAC), which was formed with two officers, one mechanic, and $5000 to purchase an aircraft from the Burgess Company in Massachusetts, for delivery to Valcartier, near Quebec City. The Burgess-Dunne biplane was delivered on 1 October 1914, and was shipped immediately to England. On arrival, the biplane was transported to Salisbury Plain where the CEF was marshalled for training. The craft never flew. It quickly deteriorated in the damp winter climate.[7] By May 1915, the CAC no longer existed.[8]

During the First World War over 20,000 Canadians volunteered to serve with the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Naval Air Service, producing such aces as William Barker, W.A. "Billy" Bishop, Naval Pilot Raymond Collishaw, Roy Brown, Donald MacLaren, Frederick McCall, and Wilfrid "Wop" May.[9] In 1917 the RFC opened training airfields in Canada to recruit and train Canadian airmen. The Canadian government advanced the RFC money to open an aircraft factory in Toronto, Canadian Aeroplanes, but did not otherwise take part.[10]

In 1915, Britain suggested that Canada should consider raising its own air units. However, it was not until spring 1918 that the Canadian government proposed forming a wing of eight squadrons for service with the Canadian Corps in France. Rather than the proposed eight squadrons, the British Air Ministry formed two Canadian squadrons (one bomber, one fighter). On 19 September 1918, the Canadian government authorized the creation of the Canadian Air Force (CAF) to take control of these two squadrons (eventually to become No 1 Wing, CAF) under the command of Canada's Lieutenant-Colonel Billy Bishop, the leading ace of the British Empire and the first Canadian aviator awarded the Victoria Cross.[9] In June 1919 the British government cut funding to the squadrons, and in February 1920, the CAF in Europe was disbanded, never having flown any operations.[11]

There had been some thought that these two European squadrons would be the nucleus of a new Canadian air force.[12] However, on 30 May 1919 the Canadian government decided against a new military air force because it was felt none was needed.[13]

Establishment

[edit]Air Board and the Canadian Air Force

[edit]Because of Canada's involvement with aviation during the First World War, the government felt obliged to further its responsibilities related to aviation in Canada. It was thought that since Canada had a large supply of trained personnel and equipment because of the war, government responsibilities could be better enabled by facilitating civil (non-military) aviation. As early as October 1917 a government committee, the Reconstruction and Development Committee, was established to examine issues related to transportation, including air transportation, in the post-war era.[14] The future of civil aviation was also determined by Canada's commitment to the International Convention for Air Navigation, part of the convention signed by Britain in Paris in 1919. Canada was required to control air navigation and traffic within its borders. For these reasons, Canada instituted the Air Board, whose task was mainly regulatory but it was also responsible for controlling civil aviation and handling air defence.[15][14]

One of the Air Board's first responsibilities was managing the operation of over 100 surplus aircraft that had been gifted to Canada by the British Government to help Canada with air defence. Several flying boat aircraft and other equipment had also been donated to Canada by the Americans who had temporarily established naval air stations on the east coast pending formation of the Royal Canadian Naval Air Service.[16] The Air Board decided to operate these aircraft in support of civil operations such as forestry, photographic surveying, and anti-smuggling patrols. Six air stations were established by the Air Board in 1920–21 for civil flying operations: Jericho Beach, Morley (later moved to High River), Ottawa, Dartmouth, Victoria Beach and Roberval.[17]

The Air Board's venture into air defence consisted of providing refresher training to former wartime pilots via a small part-time, non-permanent air militia known as the Canadian Air Force (CAF) at the old Royal Flying Corps air station, Camp Borden.[18] Political thinking at the time was that proposing a permanent military air service, especially during peacetime, would not be popular with the public.[19] This training scheme began in July 1920 and ended in March 1922 with no new pilots trained.[20]

In 1922, the Air Board with its CAF branch, the Department of Militia and Defence, and the Department of Naval Services were amalgamated to form the Department of National Defence. The CAF became a new organization and by January 1923 when the reorganization was finalized, the CAF became responsible for all flying operations in Canada, including civil aviation.[21] The CAF itself was also reorganized, effective 1 July 1922. On 25 November 1922, the six Air Board stations were declared CAF stations.[22]

Royal Canadian Air Force

[edit]The thought that the Canadian Air Force should become "Royal" was first generated when the Australian Air Force became "Royal" in August 1921. Formal application to change the title was made on 5 January 1923, and on 15 February 1923, Canada was notified that King George V had granted the title.[23] The Canadian Government, however, did not officially recognize the granting of the new title, Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), until 1 April 1924.[24]

With this designation, Canada's air force became a permanent component of Canada's defence forces.[25] The new air force was to be organized into a permanent force and an auxiliary or non-permanent Force (Non-Permanent Active Air Force, or NPAAF), but the NPAAF did not become active for another eight years.[26] The RCAF replaced the Air Board and the CAF as the regulator of Canadian civil aviation and continued civil tasks such as anti-smuggling patrols, forest fire watches, aerial forest spraying, mail delivery, mercy flights, law enforcement, and surveying/aerial photography, and there was some training. A major undertaking by the RCAF during 1927–28 was the Hudson Strait Expedition whose purpose was to investigate ice movements and navigation conditions in the Hudson Strait in preparation for the possible creation of a major shipping port on Hudson Bay at Churchill, Manitoba.[27] Another notable operation involved assisting the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in curtailing rum-running. Liquor, destined to the United States during the American Prohibition era, was being landed on Nova Scotia's remote coasts. Aircraft patrols meant to prevent this activity accounted for almost half of the civil flying carried out by the RCAF in 1932.[28]

In 1927 the management of aviation in Canada was reorganized so that the RCAF, now considered to be a military body, did not control civil flying. A new government branch, the Civil Government Air Operations (CGAO) Branch, was formed to manage air operations that supported civil departments. However, the RCAF administered the branch, and supplied almost all the aircraft and personnel. The RCAF continued to support the CGAO until the Department of Transport assumed responsibility for supporting civil departments or until these departments instituted their own flying services.[29]

Budget cuts in the early 1930s affected personnel strength, airfield construction, pilot training, aircraft purchases and operational flying. The "Big Cut" of 1932 was especially devastating to the RCAF. The NPAAF was finally formed in 1932 in response to the budget cuts.[28] The air force began to rebuild throughout the 1930s, however, and priorities were aimed at increasing the strength of the RCAF as a military organization rather than improving it to better support civil air operations.[30] New aircraft were ordered and new air stations were built. Ten auxiliary squadrons were formed between 1932 and 1938. The RCAF expanded or combined its units, and regional commands were implemented.

By the end of the 1930s the RCAF was not a major military force.[31] Aircraft were obsolete, and the RCAF had no experience in military operations. Although new pilots and other personnel had been trained, manpower was still lacking. Many of these problems would be surmounted with the implementation of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) during the Second World War.

Second World War

[edit]The outbreak of the Second World War saw the RCAF fielding eight of its eleven permanent operational squadrons, but by October 1939 15 squadrons were available (12 for homeland defence, three for overseas service). Twenty types of aircraft were in service at this point, over half being for training or transport, and the RCAF started the war with only 29 front-line fighter and bomber aircraft.[32] The RCAF reached peak strength of 215,000 (all ranks) in January 1944.[33] By the end of the war the RCAF would be the fourth largest Allied air force.[34] Approximately 13,000 RCAF personnel were killed while on operations or died as prisoners of war.[35] Another 4000 died during training or from other causes.[35]

During the war, the RCAF was involved in three areas: the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), home defence, and overseas operations.

British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

[edit]In 1939, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand agreed to train aircrew for wartime service. The training plan, known as the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), was administered by the Canadian government and commanded by the RCAF; however, a supervisory board with representatives of each of the four involved countries protected the interests of the other three countries.[36] Training airfields and other facilities were located throughout Canada. Although some aircrew training took place in other Commonwealth countries, Canada's training facilities supplied the majority of aircrew for overseas operational service.[37] Schools included initial training schools, elementary flying training schools, service flying training schools, flying instructor's schools, general reconnaissance schools, operational training units, wireless schools, bombing and gunnery schools, a flight engineers' school, air navigation schools, air observer schools, radio direction finding (radar) schools, specialist schools, and a few supplementary schools. The BCATP contributed over 130,000 aircrew to the war effort.[38]

Home defence

[edit]Home defence was overseen by two commands of the Home War Establishment: Western Air Command and Eastern Air Command. Located on the west and east coasts of Canada, these commands grew to 37 squadrons, and were responsible for protecting Canada's coasts from enemy attack and for protecting allied shipping. Threats included German U-boats along the east coast and in Atlantic shipping lanes and the potential of attack by Japanese forces. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, more squadrons were deployed to the west. Canadian units were sent to Alaska to assist the Americans in Alaska's defence during the Aleutian Islands Campaign.

Domestic RCAF squadron codes 1939–1945

[edit]| Squadron | codes | notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | fighter | |

| 2 | KO | army co-operation |

| 3 | OP | bomber / recon OTU |

| 4 | FY, BO | 1939–42, 42–45, coastal patrol |

| 5 | QN, DE | 1939–41, 42–45, coastal patrol |

| 6 | XE | coastal patrol |

| 7 | FG | torpedo bomber, coastal patrol |

| 8 | YO | bomber |

| 9 | KA, HJ | 1939–41, 42–45, coastal patrol |

| 10 | PB, JK | 1939–41, 42–45, coastal patrol |

| 11 | OY, KL | 1939–41, coastal patrol |

| 12 | QE | communications |

| 13 | MK, AP | 1939–41, 42–45, |

| 14 | AQ | fighter, photographic |

| 111 | TM, LZ | 1939–41, 42–45, fighter |

| 115 | BK, UV | 1939–41, 42–45, coastal patrol |

| 117 | EX, PQ | coastal patrol |

| 118 | RE, VW | 1939–41, 42–45, fighter |

| 119 | DM, GR | 1939–41, 42–45, bomber |

| 120 | MX, RS | coastal patrol |

| 123 | VD | fighter |

| 125 | BA | fighter |

| 126 | BV | fighter |

| 127 | TF | fighter |

| 128 | RA | fighter |

| 129 | HA | fighter |

| 130 | AE | fighter |

| 132 | ZR | fighter |

| 133 | FN | fighter |

| 135 | XP | fighter |

| 145 | EA | coastal patrol |

| 147 | SZ | bomber |

| 149 | ZM | torpedo bomber |

Overseas operations

[edit]Forty-eight RCAF squadrons were involved in overseas operational duties in Britain, northwest Europe, North Africa, and Southeast Asia. These squadrons participated in most roles, including fighter, night fighter, fighter intruder, reconnaissance, anti-shipping, anti-submarine, strategic bombing, transport, and fighter-bomber. RCAF squadrons often included non-RCAF personnel, and RCAF personnel were also members of Royal Air Force (RAF) squadrons.[39] High-scoring Canadian fighter pilots include George Beurling, Don Laubman, James (Stocky) Edwards and Robert Fumerton.[40][41]

The RCAF played key roles in the Battle of Britain, antisubmarine warfare during the Battle of the Atlantic, the bombing campaigns against German industries (notably with No. 6 Group, RAF Bomber Command), and close support of Allied forces during the Battle of Normandy and subsequent land campaigns in northwest Europe. RCAF squadrons and personnel were also involved with operations in Egypt, Italy, Sicily, Malta, Ceylon, India, and Burma.

By October 1942, the RCAF had five bomber squadrons serving with Bomber Command. 425 Squadron was made up of French-Canadians, through English was the language of command for all squadrons.[42] In January 1943, 11 bomber squadrons were formed by transferring all of the Canadians serving in the RAF to RCAF, which became No. 6 Group RCAF of Bomber Command under Air Vice-Marshal G.E. Brookes.[42] The air crews serving in 6 Group were based in the Vale of York, requiring longer flights to Germany.[42] The Vale of York was also a region inclined to be foggy and icy in the winter, making take-off and landings dangerous.[42] Furthermore, 6 Group continued to fly obsolete Wellington and Halifax bombers and only received their first Lancaster bombers in August 1943.[42]

No. 6 Group lost 100 bombers in air raids over Germany, suffering a 7% loss ratio.[42] Morale suffered because of the heavy losses, with many bombers became unserviceable, failed to take off or returned early.[42] On the night of 20 January 1944, 6 Group was ordered to bomb Berlin. Of the 147 bombers ordered to bomb Berlin, 3 could not take off, 17 turned back over the North Sea, and nine were shot down.[43] The next night, when 125 bombers were ordered to strike Berlin, 11 failed to take off, 12 turned back and 24 were shot down over Germany.[42] The losses together with the morale problems were felt to be almost a crisis, which led to a new commander for 6 Group being appointed.[42]

On February 29, 1944, Air Vice-Marshal C.M "Black Mike" McEwen took command of 6 Group and brought about improved navigational training and better training for the ground crews.[44] In March 1944, the bombing offensive against Germany was stopped and Bomber Command began bombing targets in France as a prelude to Operation Overlord[43] As France was closer to Britain than Germany, this required shorter flights and imposed less of a burden on the bomber crews.[43]

Only in October 1944 did the strategic bombing offensive resume and 6 Group went back to bombing German cities.[43] By the end of 1944, 6 Group was suffering the lowest losses of any of the Bomber Command groups and the highest accuracy in bombing targets.[43] Altogether, 9,980 Canadians were killed in bombing raids against German cities between 1940 and 1945, making the strategic bombing offensive one of the most costly operations for Canada in World War II.[43]

Overseas RCAF squadron codes 1940–1945 (400-series)

[edit]| Squadron # | Squadron Codes | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 400 | SP | recon |

| 401 | YO | fighter |

| 402 | AE | fighter |

| 403 | KH | fighter |

| 404 | EE and EO | coastal patrol, codes changed mid-war |

| 405 | LQ | bomber |

| 406 | HU | fighter |

| 407 | RR | coastal patrol |

| 408 | EQ | bomber |

| 409 | KP | fighter |

| 410 | RA | fighter |

| 411 | DB | fighter |

| 412 | VZ | fighter |

| 413 | QL | coastal patrol |

| 414 | RU | recon |

| 415 | GX, NH, 6U | coastal patrol – 1941–43, 44, bomber – 44-45 |

| 416 | DN | fighter |

| 417 | AN | fighter |

| 418 | TH | fighter bomber |

| 419 | VR | bomber |

| 420 | PT | bomber |

| 421 | AU | fighter |

| 422 | DG | coastal patrol |

| 423 | AB, YI | coastal patrol 1943, 44-45 |

| 424 | QB | bomber |

| 425 | KW | bomber |

| 426 | OW | bomber |

| 427 | ZL | bomber |

| 428 | NA | bomber |

| 429 | AL | bomber |

| 430 | G9 | recon |

| 431 | SE | bomber |

| 432 | QO | bomber |

| 433 | BM | bomber |

| 434 | IP | bomber |

| 435 | transport | |

| 436 | U6 | transport |

| 437 | Z2 | transport |

| 438 | F3 | fighter bomber |

| 439 | 5V | fighter bomber |

| 440 | I8 | fighter bomber |

| 441 | 9G | fighter |

| 442 | Y2 | fighter |

| 443 | 2I | fighter |

| 444 | ||

| 445 | ||

| 446 | ||

| 447 | ||

| 448 | ||

| 449 |

Cold War

[edit]By spring 1945, the BCATP was discontinued and the RCAF was reduced from 215,000 to 164,846 (all ranks) and by VJ Day on 2 September 1945, it was proposed that the RCAF maintain a peacetime strength of 16,000 (all ranks) and eight squadrons.[33] By the end of 1947 the RCAF had five squadrons and close to 12,000 personnel (all ranks). Peacetime activities resumed and the RCAF participated in such pursuits as aerial photography, mapping and surveying, transportation, search and rescue, and mercy missions. In March 1947 the RCAF's first helicopters, several Sikorsky H-5s, were delivered, which were used for training and search and rescue.[46] Interest in the Arctic led to several northern military expeditions supported by the RCAF.

By the end of 1948, the Soviet bloc was perceived as a serious threat to security in Europe. The Cold War had begun and peacetime activities were no longer a priority for the air force. The Canadian government began preparing to meet this threat. In December 1948 the government decided to increase the number of RCAF establishments, increase the size of and recondition existing air stations, recruit additional personnel, and obtain and produce new (jet) aircraft.[47] Although the RCAF had a jet fighter in 1948, the British de Havilland Vampire, it would be replaced, beginning in 1951 by the more effective Sabre, built under licence by Canadair. The new Avro CF-100 Canuck was also built and entered squadron service in April 1953.[48] The RCAF was the first air force to operate jet transportation aircraft with two Comets entering service in 1953.[49] Re-equipping and expansion of the air force led to the government abandoning its plans for just eight squadrons.[50]

In April 1949 Canada joined NATO, and as part of its military commitment established an Air Division (No. 1 Air Division) in Europe consisting of four wings. The first wing to form, No. 1 Fighter Wing, was established at North Luffenham, England in 1951, but later moved to Marville, France. Other RCAF wings quickly followed, with bases established at Grostenquin (No. 2 Fighter Wing), France; Zweibrücken (No. 3 Fighter Wing), West Germany; and Baden-Soellingen (No. 4 Fighter Wing), West Germany. Each of these wings consisted of three fighter squadrons. The backbone of RCAF support to NATO's air forces in Europe in the 1950s were the CF-100 and the Sabre. Until 1958 the RCAF also trained aircrew from other NATO countries under the NATO Air Training Plan.

In 1950, the RCAF was heavily involved with the transportation of personnel and supplies in support of the Korean War. The RCAF was not involved with a combat role since no jet fighter squadrons capable of the type of combat required in Korea were yet in service, and capable fighter squadrons that later did become operational were allocated to NATO duty in Europe. Twenty-two RCAF fighter pilots, however, flew on exchange duty with the USAF in Korea. Several, including Squadron Leader Joseph A.O. "Omer" Levesque, and Flight Lieutenant E. A. "Ernie" Glover scored air-to-air victories.[51]

The Soviet nuclear threat posed by a growing bomber fleet in the early 1950s saw the USAF and RCAF partner to build the Pinetree Line network of early warning radar stations across Canada at roughly the 50° north parallel of latitude with additional stations along the east and west coasts. This was expanded in the mid-1950s with the building of the Mid-Canada Line at roughly the 55° north parallel, and finally in the late-1950s and into the early 1960s the DEW Line was built across the Arctic regions of North America. The nature of the Soviet bomber threat and of other hostile incursions into North American airspace saw an RCAF and USAF partnership in the creation of the North American Air (Aerospace, after 1981) Defense Command (NORAD) which was formed on 1 August 1957.

The Soviet bomber threat posed to North America also saw the RCAF begin the development of the Avro CF-105 Arrow fighter-interceptor. The changing nature of the Soviet threat from bombers to ICBMs in the late 1950s, and pressure from the United States, saw the CF-105 program scrapped in favour of Bomarc nuclear-tipped anti-aircraft missiles.

To improve its abilities, the RCAF began replacing its 1950s-era aircraft with smaller numbers of second-generation aircraft. For instance, for air defence, the CF-101 Voodoo armed with the AIR-2 Genie nuclear-armed air-to-air missile replaced the CF-100, and Sabres were replaced by the CF-104 Starfighter, which served in a strike/reconnaissance role.

Coastal defence and peacekeeping support were also important. Maritime patrol squadrons stationed on Canada's east and west coasts were provided with Lancasters, and later Neptune, and Argus aircraft to carry on anti-submarine operations. The RCAF's peacekeeping role mainly included the transportation of troops, supplies, and truce observers to troubled areas of the world.

Many RCAF aerobatic or flight demonstration teams existed during this period. These include the Blue Devils (flying Vampires), the Fireballs (an Air Division team flying Sabres), the Sky Lancers (an Air Division team flying Sabres), the Golden Hawks (flying Sabres), the Goldilocks (flying Harvards), and the Golden Centennaires (flying Tutors).

Because of the Cold War and the Korean War, the RCAF grew to a strength of 54,000 personnel (all ranks) by 1954 and reached a 1955 peak of 41 squadrons.[52]

Unification and Air Command

[edit]

In 1964 the Canadian government began to reorganize Canada's armed forces with the aim of integrating the RCAF with the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and the Canadian Army to form the unified Canadian Forces. The purpose of the merger was to reduce costs and increase operating efficiency.[53] The Minister of National Defence, Paul Hellyer stated on 4 November 1966 that "the amalgamation...will provide the flexibility to enable Canada to meet in the most effective manner the military requirements of the future. It will also establish Canada as an unquestionable leader in the field of military organization."[54] A new National Defence Act was passed in April 1967. On 1 February 1968 the Canadian Forces Reorganization Act came into effect and the RCAF ceased to exist. The three branches of the Canadian Forces were unified into a single service with the aim of improving Canada's military effectiveness and flexibility.

Six commands were established for the unified forces:

1. Mobile Command was composed of former Canadian Army ground forces, as well as the army's tactical helicopters (CH-135 Twin Huey, CH-136 Kiowa, CH-147 Chinook, CH-113A Voyageur) and CF-5 tactical and ground attack aircraft.

2. Maritime Command operated aircraft in support of former RCN vessels as well as maritime patrol and reconnaissance missions, including CH-124 Sea King, CP-107 Argus, and the CP-121 Tracker.

3. Air Defence Command consisted primarily of CF-101 Voodoo fighter-interceptor aircraft and the radar networks of DEW Line, Mid-Canada Line and Pinetree Line early warning stations.

4. Air Transport Command was responsible for strategic airlift and refueling aircraft. Its primary role was the transportation of Mobile Command ground troops to and from distant conflict zones. The CC-137 Husky was used in this capacity.

5. Training Command was responsible for aircrew and trades training across all commands in the armed forces.

6. Materiel Command provided maintenance and supply support to the other commands.

Along with these six new commands, Communications Systems and Canadian Forces Europe were formed. Communications Systems was formed into a command in 1970. In 1971, the Snowbirds aerobatic team, flying the CT-114 Tutor trainer, was formally created to demonstrate the flying skills of Canadian air force personnel. The team continues the flying demonstration tradition of previous Canadian air force aerobatic teams. The Snowbirds were designated a squadron (No. 431 Air Demonstration Squadron) in 1978.

On 2 September 1975, the Canadian Forces transferred the air assets of all commands to a newly formed Air Command (AIRCOM). Air Defence Command and Air Transport Command were abolished. In their place, Air Defence Group and Air Transport Group were formed and made subordinate to Air Command. The air assets of Maritime Command were transferred to a newly formed Maritime Air Group. Air training became the responsibility of a newly created 14 Air Training Group and the air assets of Mobile Command were transferred to a newly formed 10 Tactical Air Group. No. 1 Canadian Air Group was formed in Europe to control all air assets there. AIRCOM closely resembled the old RCAF as the new command handled all the aviation requirements of Canada's military.

Several bases closed during the 1970s–1990s as aircraft changes took place. As CF-18A/B Hornet tactical fighter bombers were acquired, CF-104 Starfighter and CF-101 Voodoo aircraft were retired in the early-mid-1980s, leading to the closing of CFB Chatham and CFB Baden Soellingen and various bombing ranges. The CF-116 fighter aircraft and Boeing 707 transport/refuelling aircraft were retired. Also, over the years, the stations of the three radar early warning lines were modernized or closed. In the late 1970s AIRCOM replaced the CP-107 Argus and CP-121 Tracker with the CP-140 Aurora/CP-140A Arcturus maritime patrol aircraft.

Post-Cold War period

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (May 2022) |

Following the end of the Cold War, government cutbacks along with the shift of east coast maritime squadrons and units from CFB Summerside to CFB Greenwood led to the closure of CFB Summerside in 1991. Canadian Forces Europe was shut down in 1994.

In the early 1990s, AIRCOM transport and utility helicopters in support of army operations were cut back and consolidated with the purchase of the CH-146 Griffon, replacing the CH-135 Twin Huey, CH-136 Kiowa, and CH-147 Chinook. The CH-137 Husky was replaced by the Airbus CC-150 Polaris in 1997.

Search and rescue squadrons received new aircraft when the CH-149 Cormorant replaced the CH-113 Labrador beginning in 2002. The CC-115 Buffalo was replaced in the 2000s with the CC-130 Hercules at CFB Trenton and CFB Greenwood, but are still used on the west coast. Ship-borne anti-submarine helicopter squadrons are currently operating the CH-124 Sea King.

In 2007 and 2008, four C-17 Globemaster IIIs, based at CFB Trenton, were added to improve transportation capabilities. Seventeen CC-130J Super Hercules tactical transport aircraft were acquired by May 2012.[55]

On 1 July 31, 1997, all previous groups were eliminated and placed under No. 1 Canadian Air Division/Canadian NORAD Region. The new operational structure was based on 11 operational "wings" located across Canada. On 25 June 2009, 2 Canadian Air Division (2 CAD) was established to be responsible for air force training and doctrine. Units forming 2 CAD include: 15 Wing Moose Jaw, 16 Wing Borden and the Canadian Aerospace Warfare Centre located at 8 Wing Trenton.

On 16 July 2010, the Canadian government announced that the replacement for the CF-18 will be the American F-35.[56] Sixty-five would be ordered; they would be based at CFB Bagotville and CFB Cold Lake.[57] On 16 August 2011, the Canadian government announced that the name "Air Command" was being changed to the air force's original historic name: Royal Canadian Air Force. The change was made to better reflect Canada's military heritage and align Canada with other key Commonwealth countries whose militaries use the royal designation.[58][59]

From March to November 2011, six CF-18 Hornet fighter jets, two Boeing CC-177 Globemasters, two CP-140 Auroras, and approximately 250 Canadian Forces personnel were deployed as part of Operation Mobile, Canada's response to the Libyan uprising.[60] Air Command helped maintain a no-fly zone as part of Operation Odyssey Dawn. Canadian CF-18s carried out bomb strikes on Libyan military installations.[61][62][63]

In 2014, RCAF aircraft became involved with supplying military supplies to Iraq as part of Operation Impact. Several CF-18s have been conducting combat air strikes.[64]

Victoria Cross recipients

[edit]The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest award given to British and Commonwealth armed forces personnel of any rank in any service, and civilians under military command for bravery in the presence of the enemy. This honour has been granted to two members of the Royal Canadian Air Force since its inception in 1924.

- Pilot Officer Andrew Charles Mynarski, for valour during action over Cambrai, France, 12 June 1944.

- Flight Lieutenant David Ernest Hornell, for valour during action near the Faroe Islands, 24 June 1944.

Women in the RCAF

[edit]

The Canadian Women's Auxiliary Air Force (CWAAF) was formed in 1941 to take over positions that would allow more men to participate in wartime training and combat duties. The unit's name was changed to the Royal Canadian Air Force Women's Division (WD) in 1942. Although the Women's Division was discontinued in 1946 after wartime service, women were permitted to enter the RCAF in 1951 when the air force was expanding to meet Canada's NATO commitments.[65] Women were accepted as military pilots in 1980, and Canada became the first Western country to allow women to be fighter pilots in 1988.[66]

Symbols, insignia and markings

[edit]Roundels

[edit]The RCAF used British roundels and other markings until 1946, when Canada began using its own insignia identity. The British roundel existed in several versions. During the Second World War the red circle was painted out or reduced in size on some aircraft active in the Pacific theatre to avoid confusion with the Japanese Hinomaru. Roundels were also modified to be less visible on camouflaged aircraft or to make them more visible.

Canada was the first Commonwealth country to dispense with the RAF system.[67] The maple leaf replaced the British-style inner circle to give it a distinctive Canadian character. Although the maple leaf roundel was approved for use by the RCAF in 1924, it was not until after the war that it began to be used on aircraft. It was, however, used on the ensign beginning in 1941.[68] Popularization of the "maple leaf" roundel during the war years was partly achieved through unofficial means, as the Ottawa RCAF Flyers hockey team wore a variant of the future RCAF "maple leaf" roundel on team sweaters.[69] Following the Second World War, from 1946 to 1948 a roundel with a red leaf set inside a blue disk (referred to as the RCAF Type 1 roundel) was used on non-camouflaged aircraft.[70] Several versions of the maple leaf roundel existed from wartime to 1965. Sizes of the leaf and the ring thickness sometimes changed, and some versions of the RCAF roundel included a white or yellow outline, which were specific to certain aircraft.

The realistic-looking "silver maple" style of leaf (referred to as the "RCAF" roundel) was replaced with the eleven-point stylized leaf of the new Canadian flag in February 1965 (referred to as the "CAF" roundel).[71] A slightly modified standardized version of this roundel (referred to as the "CAF revision E" roundel) was used by Air Command, and continues to be used by the "new" RCAF. An all-red "unification roundel" was used on a few aircraft from 1967 to 1968. Like the RCAF roundel, this new roundel sometimes changed – mainly in the size of the leaf and ring thickness, and one version had a white ring, which was used on certain aircraft. The current RCAF also uses a low visibility tactical grey roundel.

-

RAF Type "A" roundel – an example of an RAF roundel used on aircraft 1924–1946

-

Type 1 Roundel used on non-camouflaged aircraft 1946–1948

-

One version of an RCAF roundel used on aircraft 1946–1965

-

Roundel used 1965–1968, and used by Air Command/current RCAF

-

Roundel used 1967–1968 on Yukon and a few other selected aircraft.

-

Low visibility tactical grey roundel used by Air Command/current RCAF

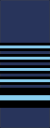

Fin flashes

[edit]RCAF aircraft used the British fin flash, which consisted of red and blue vertical bands separated by a white band. In 1955 the red ensign Canadian Flag began replacing the fin flash on aircraft based in Europe. On Canada-based aircraft the flag began replacing the flash in 1958. Beginning in 1965 the new Canadian flag was used.[67]

-

Fin flash used to 1958 (to 1955 in Europe)

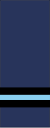

-

Flag used in place of fin flash 1958–1964 (1955–1964 in Europe)

-

Flag used on fin starting in 1965 and used by Air Command/current RCAF

-

Low visibility tactical grey fin flash used by Air Command/current RCAF

Ensign

[edit]The ensign of the original Royal Canadian Air Force was based on the RAF ensign, a light (sky) blue ensign, but with the Canadian roundel. Until the Second World War the RAF ensign was used by the RCAF; the RCAF ensign with the maple leaf roundel began to be used in 1941. The flag was discontinued when Canada's armed services were unified, but a modified version with the revised roundel and Canadian flag was re-adopted by Air Command 1985. The current RCAF maintains use of this ensign.

-

RCAF ensign 1941–1968

-

Ensign of Air Command/current RCAF (since 1985)

Badge

[edit]The badge of the original RCAF was similar to that used by the RAF, the Royal Australian Air Force and the Royal New Zealand Air Force. It consists of the Imperial Crown, an "eagle volant" (flying eagle), a circle which was formerly inscribed from 1924 to 1968 with the RCAF's motto per ardua ad astra (which is usually translated as "Through Adversity to the Stars") - this was changed in 1968 to Sic itur ad astra, translating to "such is the pathway to the stars"; in use to this day - and a scroll inscribed with "Royal Canadian Air Force". The RCAF began using a modified version of the RAF badge in 1924. Once it was learned the badge had never been officially sanctioned, the Chester Herald prepared an improved design, and in January 1943 the badge was approved by the King.[72]

The original badge disappeared when the services were unified. Air Command adopted a new design consisting of the imperial crown, an eagle "rising to sinister from the Canadian Astral crown" on an azure background, the Crown of Stars, which represents Air Command, and a new motto.[73] This badge was replaced by a new badge in September 2013. The new badge includes the eagle volant used in the pre-unification RCAF badge.[74]

Tartan

[edit]The Royal Canadian Air Force Tartan was designed by Kinloch Anderson Ltd. in Edinburgh, Scotland at the request of the RCAF, and is based on the Anderson tartan.[75] Colors are primarily dark blue, light blue, and maroon. The design was officially endorsed by the Air Council in May 1942. The tartan was used on RCAF pipe band kilts and on other articles of clothing and regalia. After unification of Canada's armed forces, the tartan continued to be used.

Ranks and uniforms

[edit]Ranks

[edit]The original Royal Canadian Air Force used a rank structure[76] similar to that of the Royal Air Force, with the exceptions, in the enlisted ranks, of the RCAF having the ranks of warrant officer 1 and 2, not having the ranks of senior aircraftman or junior technician, and not distinguishing between aircrew and non-aircrew for sergeants and above. The rank structure is almost identical to that of the Royal Australian Air Force, once again with the exception of warrant officer 2. RCAF Women's Division personnel used a different rank structure. When the age limit for British Commonwealth Air Training Plan aircrew recruits was lowered to seventeen in 1941, the recruits were placed into the temporary rank of "boy" until they reached their eighteenth birthday and became eligible for flying training.[77] With the exception of the rank of "aviator", the current RCAF uses the army-style ranks instituted by the Canadian Forces when unification took place in 1968.

This chart compares ranks of the former and current RCAF. Ranks are listed with the most senior rank at the top.

| Royal Canadian Air Force (to 1968) |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Air chief marshal / A/C/M

French: maréchal en chef de l’Air |

General / Gen | |

| Air marshal / A/M

French: maréchal de l’Air |

Lieutenant-general / LGen | |

| Air vice-marshal / A/V/M

French: vice-maréchal de l’Air |

Major-general / MGen | |

| Air commodore / A/C

French: commodore de l’Air |

Brigadier-general / BGen | |

| Group captain / G/C

French: colonel d’aviation |

Colonel / Col | |

| Wing commander / W/C

French: lieutenant-colonel d’aviation |

Lieutenant-colonel / LCol | |

| Squadron Leader / S/L

French: commandant d’aviation |

Major / Maj | |

| Flight Lieutenant / F/L

French: capitaine d’aviation |

Captain / Capt | |

| Flying officer / F/O

French: lieutenant d’aviation |

Lieutenant / Lt | |

| Pilot officer / P/O

French: sous-lieutenant d’aviation |

Second lieutenant / 2Lt | |

French: élève-officier |

Officer cadet / OCdt | |

| Warrant officer, class 1 / WO1

French: adjudant de 1re classe |

Chief warrant officer / CWO | |

| Warrant officer, class 2 / WO2

French: adjudant de 2e classe |

Master warrant officer / MWO | |

| Flight sergeant / FS

French: sergent de section |

Warrant officer / WO | |

| Sergeant / Sgt

French: sergent |

Sergent / Sgt | |

| Corporal / Cpl

French: caporal |

| |

| Aircraftman

French: aviateur |

French: aviateur-chef |

|

French: aviateur 1re classe | ||

French: aviateur 2e classe | ||

Commander-in-Chief

[edit]| Canada | Commander-in-chief |

|---|---|

| Insignia |

|

| Title | Commander-in-chief |

| Abbreviation | C-in-C |

Officers

[edit]| NATO Code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) | Student Officer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Canadian Air Force (1924–1968) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No Equivalent |

|

| Rank titles (1924–1968) |

Marshal of the RCAF (never filled)[80] |

Air chief marshal | Air marshal | Air vice-marshal | Air commodore | Group captain | Wing commander | Squadron leader | Flight lieutenant | Flying officer | Pilot officer | Flight cadet/ Officer cadet (post-1962) | |

| Maréchal du ARC | Maréchal en chef de l’Air | Maréchal de l’Air | Vice-maréchal de l’Air | Commodore de l’Air | Colonel d’aviation | Lieutenant-colonel d’aviation | Commandant d’aviation | Capitaine d’aviation | Lieutenant d’aviation | Sous-lieutenant d’aviation | Élève-officier | ||

| Air Command (1968–1984) |

No Equivalent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Air Command (1984–2014) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| Royal Canadian Air Force (2014–present) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| Rank titles (1968–present) |

General | Lieutenant-general | Major-general | Brigadier-general | Colonel | Lieutenant-colonel | Major | Captain | Lieutenant | Second lieutenant |

Officer Cadet | ||

| Général | Lieutenant-général | Major-général | Brigadier-général | Colonel | Lieutenant-colonel | Major | Capitaine | Lieutenant | Sous-lieutenant | Élève-Officier | |||

Non-commissioned members

[edit]| NATO code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Force (1948–1953) |

|

|

|

No equivalent | No equivalent | No Insignia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Air Force (1953–1968) |

|

|

|

|

No Insignia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank titles (1948–1968) |

Warrant officer first class | Warrant officer second class | Flight sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Leading aircraftman/aircraftwoman | Aircraftman/Aircraftwoman first class | Aircraftman/Aircraftwoman second class | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adjudant de 1re classe | Adjudant de 2e classe | Sergent de section | Sergent | Caporal | Aviateur-chef | Aviateur 1re classe | Aviateur 2e classe | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Air Command (1968–1984) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Air Command (1984–2014) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Royal Canadian Air Force (2014–present) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank titles (1968–present) |

Chief warrant officer | Master warrant officer | Warrant officer | Sergeant | Master corporal | Corporal | Private (1968-2014)/Aviator | Private (basic) (1968-2014)/Aviator (basic) | Private (recruit (1968-2014)/Aviator (recruit) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adjudant-chef | Adjudant-maître | Adjudant | Sergent | Caporal-chef | Caporal | Soldat (1968-2014)/Aviateur | Soldat (Confirmé) (1968-2014)/Aviateur (Confirmé) | Soldat (Recrue) (1968-2014)/Aviateur (Recrue) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Uniforms

[edit]Uniforms of the original RCAF were nearly identical to the Royal Air Force and other Dominion air forces in cut, colour and insignia. Personnel wore RAF-pattern blue battledress, though some personnel in the 2nd Tactical Air Force and in the Pacific also wore army khaki battledress with standard RCAF insignia. A khaki-drill uniform was introduced for wear in summer and warm climates.

During the Second World War Canadian airmen and airwomen posted outside Canada wore a Canada nationality shoulder flash, as did Canadians serving with the RAF. This was usually light blue lettering on curved blue-grey for commissioned officers and Warrant Officer 1, and light blue lettering curved above an eagle for other ranks, except for warm weather uniforms, which had red embroidery on khaki-drill. Later in the war all RCAF personnel wore this nationality distinction, which was continued until unification.

After the war, the insignia for Warrant Officer I changed from the Royal coat of arms to the Canadian coat of arms. Along with the rest of the Commonwealth, insignia using the Imperial Crown changed from the Tudor Crown to the St. Edward's Crown after the accession of Queen Elizabeth II to the Throne of Canada.

After unification, all personnel in the Canadian Forces wore a rifle green uniform with only cap and collar badges (a modified version of the former RCAF badge) as distinguishing marks for pilots and aircrew. Use of this uniform continued under Air Command from 1975 until the mid-1980s, when Air Command adopted a blue "distinctive environmental uniform". This uniform continued to be used until 2015 when the rank structure and insignia changed.[81] Insignia changed from golden yellow to a pearl-grey colour similar to that worn before unification of Canada's Armed Forces in 1968 and the button color was changed. Other changes reflect the replacement of the rank of "private" with that of "aviator", and officers' tunic sleeve insignia were modified.[82]

Leadership

[edit]The Commander of the Royal Canadian Air Force is the institutional head of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Starting with the Canadian Air Force in 1920, air force commanders have had several titles: Officer Commanding, Director, Senior Air Officer, Chief of the Air Staff, and Commander. In August 2011, with the restoration of the Royal Canadian Air Force name, the title "Chief of the Air Staff" was changed to "Commander of the Royal Canadian Air Force."[83]

Canada's air force in film

[edit]- Captains of the Clouds (1942). About Canadian bush pilots in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Stars James Cagney.

- Wings on her Shoulder (1943). National Film Board of Canada documentary about the Women's Division.

- Train Busters (1943). National Film Board of Canada documentary about RCAF air power during the Second World War.

- Wasp Wings (1945). National Film Board of Canada documentary about three RCAF wings of the RAF Second Tactical Air Force.

- Canada's Air Defence (1956). National Film Board of Canada documentary about the RCAF's role in air defence.

- Fighter Wing (1956). National Film Board of Canada documentary about RCAF pilots in West Germany.[84]

- Airwomen (1956). National Film Board of Canada film about a fighter control operator who ends up being posted to Canada's NATO force in Germany.[85]

- For the Moment (1993). About airmen training on a Manitoba British Commonwealth Air Training Plan station and their romantic involvements. Stars Russell Crowe.

- Ordeal in the Arctic (1993). A Canadian Forces CC-130 Hercules aircraft crashes on Ellesmere Island. Stars Richard Chamberlain.

- Lost Over Burma: Search for Closure (1997). National Film Board of Canada documentary about the recovery of the crew of an RCAF 435 Squadron Dakota aircraft lost in Burma during the Second World War.

- Last Flight to Berlin: The Search for a Bomber Pilot (2005). The adult son of an RCAF 434 Squadron Halifax bomber pilot who died when the aircraft crashed during a bombing raid on Berlin sets off to find out more about his father, to document his story, visit the crash site, and meet the German fighter pilot who shot down his father's aircraft.[86]

- Jetstream (2008). Documentary television series that follows pilots training to fly the CF-18 Hornet

See also

[edit]- Royal Canadian Air Force Association

- History of aviation in Canada

- List of Royal Canadian Air Force squadrons

- List of Royal Canadian Air Force stations

- List of aircraft of Canada's air forces

- Royal Canadian Air Force Police

- RCAF March Past

- Royal Air Force roundels

- Royal Canadian Air Force Band

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Milberry 1984, p.14-16

- ^ Milberry 1984, p.367

- ^ Roberts 1959, p. 3.

- ^ Greenhous 1999, p. 13.

- ^ a b Roberts 1959, p. 6.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Milberry 1984, p. 13.

- ^ The History of Canada's Air Force – The Beginning – Canadian Aviation Corps. 1914–1915 Archived 2011-05-18 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2011-04-27

- ^ a b Milberry 1984, p. 15.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 14.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 16.

- ^ Greenhous 1999, p. 23.

- ^ Greenhous 1999, p. 24.

- ^ a b Orr, J.L. (Spring 2021). "The Way of An Eagle In the Air. The Canadian Air Board and the First Trans-Canada Flight" (PDF). Royal Canadian Air Force Journal vol.10 No 2. Canadian Armed Forces National Defence. Retrieved 2024-04-23.

- ^ Milberry 1984, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Greenhous 1999, pp.20, 24.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 20.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 17.

- ^ Roberts 1959, p. 33.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 21.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 21-22.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p.461,462.

- ^ Roberts 1959, p. 54.

- ^ Roberts 1959, p. 55.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p.462.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 23.

- ^ Roberts 1959, pp. 91-93.

- ^ a b Greenhous 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Milberry 1984, pp. 24, 25.

- ^ Greenhouse 1999, p. 37

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 55.

- ^ RCAF.com – Canadian Air Force History – The War Years Archived 2010-03-17 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-04-29

- ^ a b Roberts 1959, p. 237.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 97.

- ^ a b Greenhous 1999, p. 120.

- ^ Hatch 1983, p. 21.

- ^ Hatch 1983, p. 109.

- ^ Hatch 1983, p. 2.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 130.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 134, 136, 142.

- ^ Roberts 1959, p. 216.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Morton, Desmond A Military History of Canada. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1999. pg 206.

- ^ a b c d e f Morton, Desmond A Military History of Canada, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1999 page 207.

- ^ Morton, Desmond A Military History of Canada, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1999 pages 206-207.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 131.

- ^ Milberry 1984, pp. 207-208.

- ^ Roberts 1959, p. 238.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 282.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 89.

- ^ Roberts 1959, p. 273.

- ^ Milberry 1984, pp. 259, 266.

- ^ History of the Royal Canadian Air Force – The Cold War (canadianwings.com) Archived 2010-03-17 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2010-02-20

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 366.

- ^ Milberry 1984, p. 367.

- ^ "Final CC-130J Hercules Transport Aircraft Delivery Ahead of Schedule." Archived 2012-05-16 at the Wayback MachineCanada's Air Force, 11 May 2012. Retrieved: 11 May 2012.

- ^ Bryn Weese (2010-07-16). "Tories Spend $16billion on Jet Fighters". canoe.ca – cnews – Politics. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "defence.professionals, defpro.com". Archived from the original on 2010-09-20. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ^ Galloway, Gloria (15 August 2011). "Conservatives to restore 'royal' monikers for navy, air force". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 2011-09-23.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Meagan (16 August 2011). "Peter MacKay hails 'royal' renaming of military". CBC News. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-09-23.

- ^ "Update on CF Operations in Libya"[permanent dead link] Canadian Forces website, 22 March 2011

- ^ "Canadian jets bomb Libyan target in first attack". The Globe and Mail. 23 March 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Canadian jets target Libyan ammunition depot". CBC News. 23 March 2011. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ Murray Brewster The Canadian Press (1932-02-27). "Canadian CF-18s bomb Libyan ammunition depot". thestar.com. Archived from the original on 2011-03-26. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ Operation Impact Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2015-04-04

- ^ Ziegler 1972, p. 160.

- ^ "The Royal Canadian Air Force Women’s Division." Archived 2015-02-07 at the Wayback Machine Juno Beach. Retrieved: 10 February 2015.

- ^ a b Canadian Military Aircraft Markings Archived 2008-04-27 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2010-02-20

- ^ Canada, Air Force Ensign Archived 2008-10-07 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2010-02-20

- ^ O'Malley, Dave (2013). "Roundel Round-Up – The Roundel – Part of Canadian Popular Culture". vintagewings.ca. Vintage Wings of Canada. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ Roundel information print: The Silver Maple from canmilair.com Archived 2010-02-24 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2011-02-15.

- ^ Canada's Air Force – The Roundel Archived 2011-06-11 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2010-02-20

- ^ The Great Eagle-Albatross Controversy

- ^ Air Command Insignia Retrieved 2011-09-27

- ^ The New Royal Canadian Air Force Badge Archived 2017-10-18 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2013-09-17

- ^ Dempsey 2002, p. 701.

- ^ Hatch 1983, p. 180.

- ^ Quigley, George (2007). RCAF Dress Regulations. Ottawa: Service Publications. ISBN 978-1-894581-45-5.

- ^ Queen's Regulations and Orders Chap 3.08 Master Corporal Appointment Archived 2013-11-20 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2013-12-06

- ^ CAP 6 Dress Orders for the Royal Canadian Air Force. Ottawa: RCAF, 1958. pp. 3–62.

- ^ "New Royal Canadian Air Force uniform unveiled". Ottawa. 21 September 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-09-24. Retrieved 2015-04-01.

- ^ "DND Backgrounder". Archived from the original on 2014-12-18. Retrieved 2015-04-01.

- ^ Canadian Navy, Air Force 'Royal' Again With Official Name Change Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine Huffington Post, 15 August 2011

- ^ Fighter Wing (NFB) Archived 2018-01-30 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2018-01-29

- ^ "Airwomen". National Film Board. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Last Flight to Berlin: The Search for a Bomber Pilot, Janson Media Archived 2015-01-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2015-01-22

- Bibliography

- Greenhous, Brereton; Halliday, Hugh A. Canada's Air Forces, 1914–1999. Montreal: Editions Art Global and the Department of National Defence, 1999. ISBN 2-920718-72-X.

- Hatch, F.J. Aerodrome of Democracy: Canada and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan 1939–1945. Archived 2014-02-11 at the Wayback Machine Ottawa: Canadian Department of National Defence, 1983. ISBN 0-660-11443-7. Retrieved: 2010-04-26.

- Milberry, Larry, ed. Sixty Years—The RCAF and CF Air Command 1924–1984. Toronto: Canav Books, 1984. ISBN 0-9690703-4-9.

- Roberts, Leslie. There Shall Be Wings. Toronto: Clark, Irwin and Co. Ltd., 1959. No ISBN.

- Royal Canadian Air Force. The R.C.A.F. Overseas: The First Four Years – With an Introduction by Major The Honourable C.G. Power. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1944.

- Dempsey, Daniel V. A Tradition of Excellence: Canada's Airshow Team Heritage. Victoria, BC: High Flight Enterprises, 2002. ISBN 0-9687817-0-5.

- Johnson, Vic. "Canada's Air Force Then and Now". Airforce magazine. Vol. 22, No. 3. 1998. ISSN 0704-6804.

- Shores, Christopher. "History of the Royal Canadian Air Force". Royce Publications, Toronto, 1984. ISBN 0-86124-160-6.

- RCAF insignia Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- Roundel information print:The Early Years from canmilair.com Retrieved: 2010-02-11.

- Roundel information print: The Silver Maple from canmilair.com Retrieved: 2010-02-12.

- Roundel information print: The New Leaf from canmilair.com Retrieved: 2010-02-12.

- "Roundel Round-Up" - Vintage Wings of Canada's history of British and Canadian roundel styles from 1914 through and into the 21st century Archived 2015-04-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2015-01-09

- Canadian Air Force Ensign Retrieved: 2011-11-02.

- Library and Archives Canada[permanent dead link] Retrieved: 2014-07-20

- Air Force History Retrieved: 2014-07-20

- Ziegler, Mary. We Serve That Men May Fly – The Story of the Women's Division of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Hamilton: RCAF (WD) Association, 1973. No ISBN.

Further reading

[edit]- Dempsey, Sandra - "Flying To Glory ~ Prairie Boys Take Flight in the Royal Canadian Air Force in World War II" - Touchwood Press, 2006 [ISBN 096878616-2] - drama - Boyhood pals embark on the adventure of a lifetime by enlisting in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1942. http://www.SandraDempsey.com

- Bashow, David L. No Prouder Place: Canadians and the Bomber Command Experience 1939–1945. St. Catharine's, Ontario, Canada: Vanwell Publishing Limited, 2005. ISBN 1-55125-098-5.

- Blyth, K.K. Cradle Crew: Royal Canadian Air Force, World War II. Sunflower University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-89745-217-8.

- Douglas, W.A.B. The Official history of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Toronto, Ontario, University of Toronto and the Department of National Defence, 1980. ISBN 0-8020-2584-6.

- Dunmore, Spencer and Carter, William. Reap the Whirlwind: The Untold Story of 6 Group, Canada's Bomber Force of World War II. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: McLelland and Stewart Inc., 1991. ISBN 0-7710-2924-1.

- Faryon, Cynthia. Unsung Heroes of the Royal Canadian Air Force: Incredible Tales of Courage and Daring During World War II. Altitude Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-55153-977-2.

- Milberry, Larry. The Royal Canadian Air Force at War 1939–1945. Canav Books, 1990. ISBN 0-921022-04-2.

- Pigott, Peter. Flying Canucks: Famous Canadian Aviators. Toronto, Ontario: Hounslow Press, 2004. ISBN 0-88882-175-1.

- Shores, Christopher. History of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Royce Publications, 1984. ISBN 0-86124-160-6

- Wise, S. F. Canadian Airmen and the First World War The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force, Vol. I. Toronto, Ontario. University of Toronto Press, 1980. ISBN 0-8020-2379-7.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Air Force Association of Canada

- Canadian Wings – The History & Heritage of Canada's air force

- National Air Force Museum of Canada, Trenton, Ontario, Canada

- Experiences of RCAF Bomber Crews

- Wings Over Alberta – RCAF Uniforms

- Royal Canadian Air Force – A Return to the Royal Canadian Air Force Ranks: A Historical Examination

- "Roundel Round-Up" - Vintage Wings of Canada's history of British and Canadian roundel styles from 1914 through and into the 21st century Archived 2015-04-03 at the Wayback Machine