Isis

| Isis | |

|---|---|

Goddess of health, marriage, and wisdom | |

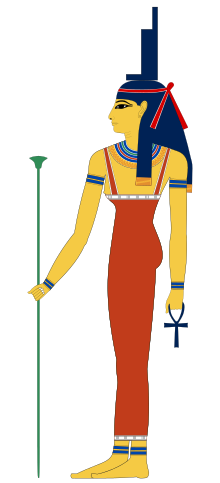

The goddess Isis portrayed as a woman, wearing a headdress shaped like a throne and with an Ankh in her hand | |

| Major cult center | Philae, Abydos |

| Symbol | the throne, the sun disk with cow's horns, sparrow, cobra, vulture, sycamore tree, kite (bird) |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Geb and Nut |

| Siblings | Osiris, Set, Nephthys and Haroeris |

| Consort | Osiris |

| Offspring | Horus, Bastet, and possibly Ammit |

Isis (/ˈaɪsɪs/; Ancient Greek: Ἶσις IPA: [îː.sis]; original Egyptian pronunciation more likely "Aset" or "Iset"[1]) is a goddess from the polytheistic pantheon of Egypt. She was first worshiped in ancient Egyptian religion, and later her worship spread throughout the Roman Empire and the greater Greco-Roman world. Isis is still widely worshiped by many pagans today in diverse religious contexts; including a number of distinct pagan religions, the modern Goddess movement, and interfaith organizations such as the Fellowship of Isis.

Isis was worshipped as the ideal mother and wife as well as the patroness of nature and magic. She was the friend of slaves, sinners, artisans and the downtrodden, but she also listened to the prayers of the wealthy, maidens, aristocrats and rulers.[2] Isis is often depicted as the mother of Horus, the falcon-headed deity associated with king and kingship (although in some traditions Horus's mother was Hathor). Isis is also known as protector of the dead and goddess of children.

The name Isis means "Throne".[3] Her headdress is a throne. As the personification of the throne, she was an important representation of the pharaoh's power. The pharaoh was depicted as her child, who sat on the throne she provided. Her cult was popular throughout Egypt, but her most important temples were at Behbeit El-Hagar in the Nile delta, and, beginning in the reign with Nectanebo I (380–362 BCE), on the island of Philae in Upper Egypt.

In the typical form of her myth, Isis was the first daughter of Geb, god of the Earth, and Nut, goddess of the Sky, and she was born on the fourth intercalary day. She married her brother, Osiris, and she conceived Horus with him. Isis was instrumental in the resurrection of Osiris when he was murdered by Set. Using her magical skills, she restored his body to life after having gathered the body parts that had been strewn about the earth by Set.[4]

This myth became very important during the Greco-Roman period. For example, it was believed that the Nile River flooded every year because of the tears of sorrow which Isis wept for Osiris. Osiris's death and rebirth was relived each year through rituals. The worship of Isis eventually spread throughout the Greco-Roman world, continuing until the suppression of paganism in the Christian era.[5] The popular motif of Isis suckling her son Horus, however, lived on in a Christianized context as the popular image of Mary suckling her infant son Jesus from the fifth century onward.[6]

Etymology

| |||||||

| Isis in hieroglyphs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Greek name version of Isis is close to her original, Egyptian name spelling (namely Aset).[1] Isis' name was originally written with the signs of a throne seat (Gardiner sign Q1, pronounced "as" or "is"), a bread loaf (Gardiner sign X1, pronounced "t" or "tj") and with an unpronounced determinative of a sitting woman. A second version of the original was also written with the throne seat and the bread loaf, but ended with an egg symbol (Gardiner sign H8) which was normally read "set", but here it was used as a determinative to promote the correct reading. The grammar, spelling and used signs of Isis' name never changed during time in any way, making it easy to recognize her any time.[1]

However, the symbolic and metaphoric meaning of Isis' name remains unclear. The throne seat sign in her name might point to a functional role as a goddess of kingship, as the maternal protector of the ruling king. Thus, her name could mean "she of the kings' throne". But all other Egyptian deities have names that point to clear cosmological or nature elemental roles (Râ = the sun; Ma'at = justice and world order), thus the name of Isis shouldn't be connected to the king himself.[1] The throne seat symbol might alternatively point to a meaning as "throne-mother of the gods", making her the highest and most powerful goddess before all other gods. This in turn would supply a very old existence of Isis, long before her first mentioning during the late Old Kingdom, but this hypothesis remains unproven.[1] A third possible meaning might be hidden in the egg-symbol, that was also used in Isis' name. The egg-symbol always represented motherhood, implying a maternal role of Isis. Her name could mean "mother goddess", pointing to her later, mythological role as the mother of Horus. But this remains problematic, too: the initial mother-goddess of Horus was Hathor, not Isis.[1]

Principal features of the cult

Origins

Most Egyptian deities were first worshipped by very local cults, and they retained those local centres of worship even as their popularity spread, so that most major cities and towns in Egypt were known as the home of a particular deity. However, the origins of the cult of Isis are very uncertain. In fact, Egyptologists such as Maria Münster[7] and Jan Assmann[8] point to the lack of archaeological evidences for a goddess 'Isis' before the time of the late Old Kingdom of Egypt.[7]

The first secure references to Isis date back to the 5th dynasty, when her name appears in the sun temple of king Niuserre and on the statue of a priest named Pepi-Ankh, who worshipped at the very beginning of 6th dynasty and bore the title "high priest of Isis and Hathor".[7] Also, according to Veronica Ions' book Egyptian Mythology from 1981 on page 56, "Isis (or Eset) was also originally an independent and popular deity whose followers were established in pre- dynastic times in the northern Delta, at Sebennytos."

Classical Egyptian period

During the Old Kingdom period, Isis was represented as the wife or assistant to the deceased pharaoh. Thus she had a funerary association, her name appearing over eighty times in the pharaoh's funeral texts (the Pyramid Texts). This association with the pharaoh's wife is consistent with the role of Isis as the spouse of Horus, the god associated with the pharaoh as his protector, and then later as the deification of the pharaoh himself.

But in addition, Isis was also represented as the mother of the "four sons of Horus", the four deities who protected the canopic jars containing the pharaoh's internal organs. More specifically, Isis was viewed as the protector of the liver-jar-deity, Imsety.[9] By the Middle Kingdom period, as the funeral texts began to be used by members of Egyptian society other than the royal family, the role of Isis as protector also grew, to include the protection of nobles and even commoners.[citation needed]

By the New Kingdom period, in many places, Isis was more prominent than her spouse. She was seen as the mother of the pharaoh, and was often depicted breastfeeding the pharaoh. It is theorized that this displacement happened through the merging of cults from the various cult centers as Egyptian religion became more standardized.[citation needed] When the cult of Ra rose to prominence, with its cult center at Heliopolis, Ra was identified with the similar deity, Horus. But Hathor had been paired with Ra in some regions, as the mother of the god. Since Isis was paired with Horus, and Horus was identified with Ra, Isis began to be merged with Hathor as Isis-Hathor. By merging with Hathor, Isis became the mother of Horus, as well as his wife. Eventually the mother role displaced the role of spouse. Thus, the role of spouse to Isis was open and in the Heliopolis pantheon, Isis became the wife of Osiris and the mother of Horus/Ra. This reconciliation of themes led to the evolution of the myth of Isis and Osiris.[9]

Temples and priesthood

-

Temple of Isis at Philae. The Court. 1893. Wilbour Library of Egyptology, Brooklyn Museum

-

Philae, Egypt. Temple of Isis., n.d. Brooklyn Museum Archives

-

Philae. Temple of Isis. Columns., n.d. Brooklyn Museum Archives

-

Philae. Temple of Isis., n.d., Brooklyn Museum Archives

Isis worship typically took place within an Iseum. In Egypt, Isis would have received the same sort of rituals as other Egyptian Deities, including daily offerings. She was served by both priests and priestesses throughout the history of her cult. By the Greco-Roman era, the majority of her priests and priestesses had a reputation for wisdom and healing, and were said to have other special powers, including dream interpretation and the ability to control the weather, which they did by braiding or not combing their hair.[citation needed] The latter was believed because the Egyptians considered knots to have magical powers.

The cult of Isis and Osiris continued at Philae up until the 450s CE, long after the imperial decrees of the late 4th century that ordered the closing of temples to "pagan" gods. Philae was the last major ancient Egyptian temple to be closed.[10]

Iconography

Associations

| ||

| "tyet" Knot of Isis in hieroglyphs | ||

|---|---|---|

Due to the association between knots and magical power, a symbol of Isis was the tiet or tyet (meaning welfare/life), also called the Knot of Isis, Buckle of Isis, or the Blood of Isis, which is shown to the right. In many respects the tyet resembles an ankh, except that its arms point downward, and when used as such, seems to represent the idea of eternal life or resurrection. The meaning of Blood of Isis is more obscure, but the tyet often was used as a funerary amulet made of red wood, stone, or glass, so this may simply have been a description of the appearance of the materials used.[11][12][13]

The star Sopdet (Sirius) is associated with Isis. The appearance of the star signified the advent of a new year and Isis was likewise considered the goddess of rebirth and reincarnation, and as a protector of the dead. The Book of the Dead outlines a particular ritual that would protect the dead, enabling travel anywhere in the underworld, and most of the titles Isis holds signify her as the goddess of protection of the dead.

Depictions

In art, originally Isis was pictured as a woman wearing a long sheath dress and crowned with the hieroglyphic sign for a throne. Sometimes she is depicted as holding a lotus, or, as a sycamore tree. One pharaoh, Thutmose III, is depicted in his tomb as nursing from a sycamore tree that has a breast.

After she assimilated many of the roles of Hathor, Isis's headdress was replaced with that of Hathor: the horns of a cow on her head, with the solar disk between them, and often with her original throne symbol atop the solar disk. Sometimes she also is represented as a cow, or with a cow's head. She is often depicted with her young child, Horus (the pharaoh), with a crown, and a vulture. Occasionally she is represented as a kite flying above the body of Osiris or with the dead Osiris she works her magic to bring him back to life.

Most often Isis is seen holding an ankh (the sign for "life") and a simple lotus staff, but in late images she is sometimes seen with the sacred sistrum rattle and the fertility-bearing menat necklace, items usually associated with Hathor. In The Book of Coming Forth By Day Isis is depicted standing on the prow of the Solar Barque with her arms outstretched.[2]

Mythology

Sister-wife to Osiris

During the Old Kingdom period, the pantheons of individual Egyptian cities varied by region. During the 5th dynasty, Isis entered the pantheon of the city of Heliopolis. She was represented as a daughter of Nut and Geb, and sister to Osiris, Nephthys, and Set. The two sisters, Isis and Nephthys, often were depicted on coffins, with wings outstretched, as protectors against evil. As a funerary deity, she was associated with Osiris, lord of the underworld, and was considered his wife.

A later myth, when the cult of Osiris gained more authority, tells the story of Anubis, the god of the underworld. The tale describes how Nephthys was denied a child by Set and disguised herself as her twin, Isis, to seduce him. The plot succeeded, resulting in the birth of Anubis.

In fear of Set's retribution, Nephthys persuaded Isis to adopt Anubis, so that Set would not find out and kill the child. The tale describes both why Anubis is seen as an underworld deity (he becomes the adopted son of Osiris), and why he could not inherit Osiris's position (as he was not actually the son of Osiris but of his brother Set), neatly preserving Osiris's position as lord of the underworld.

The most extensive account of the Isis-Osiris story known today is Plutarch's Greek description written in the 1st century CE, usually known under its Latin title De Iside et Osiride.[15]

In that version, Set held a banquet for Osiris in which he brought in a beautiful box and said that whoever could fit in the box perfectly would get to keep it. Set had measured Osiris in his sleep and made sure that he was the only one who could fit the box. Several tried to see whether they fit. Once it was Osiris's turn to see if he could fit in the box, Set closed the lid on him so that the box was now a coffin for Osiris. Set flung the box in the Nile so that it would drift far away. Isis went looking for the box so that Osiris could have a proper burial. She found the box in a tree in Byblos, a city along the Phoenician coast, and brought it back to Egypt, hiding it in a swamp. But Set went hunting that night and found the box. Enraged, Set chopped Osiris's body into fourteen pieces and scattered them all over Egypt to ensure that Isis could never find Osiris again for a proper burial.[16][17]

Isis and her sister Nephthys went looking for these pieces, but could only find thirteen of the fourteen. Fish had swallowed the last piece, his phallus. With Thoth's help she created a golden phallus, and attached it to Osiris’s body. She then transformed into a kite, and with the aid of Thoth’s magic conceived Horus the Younger. The number of pieces is described on temple walls variously as fourteen and sixteen, one for each nome or district.[17]

Mother/Sister of Horus

Yet another set of late myths detail the adventures of Isis after the birth of Osiris's posthumous son, Horus. Isis was said to have given birth to Horus at Khemmis, thought to be located on the Nile Delta.[18] Many dangers faced Horus after birth, and Isis fled with the newborn to escape the wrath of Set, the murderer of her husband. In one instance, Isis heals Horus from a lethal scorpion sting; she also performs other miracles in relation to the cippi, or the plaques of Horus. Isis protected and raised Horus until he was old enough to face Set, and subsequently become the pharaoh of Egypt. In some stories, Isis is referred to as Horus' sister.

Magic

It was said that Isis tricked Ra into telling her his "secret name" by causing a snake to bite him, the antidote to whose venom only Isis possessed. Knowing his secret name thus gave her power over him. The use of secret names became central in many late Egyptian magic spells. By the late Egyptian historical period, after the occupations by the Greeks and the Romans, Isis became the most important and most powerful deity of the Egyptian pantheon because of her magical skills. Magic is central to the entire mythology of Isis, arguably more so than any other Egyptian deity.

Isis had a central role in Egyptian magic spells and ritual, especially those of protection and healing. In many spells her powers are merged with those of her son Horus. His power accompanies hers whenever she is invoked. In Egyptian history the image of a wounded Horus became a standard feature of Isis's healing spells, which typically invoked the curative powers of Isis' milk.[19]

Greco-Roman world

Interpretatio graeca

Using the comparative methodology known as interpretatio graeca, the Greek historian Herodotus (5th century BCE) described Isis by comparison with the Greek goddess Demeter, whose mysteries at Eleusis offered initiates guidance in the afterlife and a vision of rebirth. Herodotus says that Isis was the only goddess worshiped by all Egyptians alike.[20]

After the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great and the Hellenization of the Egyptian culture initiated by Ptolemy I Soter, Isis became known as Queen of Heaven.[21] Other Mediterranean goddesses, such as Demeter, Astarte, and Aphrodite, became identified with Isis, as did the Arabian goddess Al-‘Uzzá through a similarity of name, since etymology was thought to reveal the essential or primordial nature of the thing named.[22] An alabaster statue of Isis from the 3rd century BCE, found in Ohrid, in the Republic of Macedonia, is depicted on the obverse of the Macedonian 10 denar banknote, issued in 1996.[23]

Isis in the Roman Empire

Tacitus writes that after the assassination of Julius Caesar, a temple in honour of Isis had been decreed, but was suspended by Augustus as part of his program to restore traditional Roman religion. The emperor Caligula, however, was open to Egyptian religion, and the Navigium Isidis, a procession in honor of Isis, was established in Rome during his reign.[24] According to the Jewish historian Josephus, Caligula donned female garb and took part in the mysteries he instituted. Vespasian, along with Titus, practised incubation in the Roman Iseum. Domitian built another Iseum along with a Serapeum. In a relief on the Arch of Trajan in Rome, the emperor appears before Isis and Horus, presenting them with votive offerings of wine.[24] Hadrian decorated his villa at Tibur with Isiac scenes. Galerius regarded Isis as his protector.[25]

The religion of Isis thus spread throughout the Roman Empire during the formative centuries of Christianity. Wall paintings and objects reveal her pervasive presence at Pompeii, preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE. In Rome, temples were built (such as the Temple of Isis and Serapis) and obelisks erected in her honour. In Greece, the cult of Isis was introduced to traditional centres of worship in Delos, Delphi, Eleusis and Athens, as well as in northern Greece. Harbours of Isis were to be found on the Arabian Sea and the Black Sea. Inscriptions show followers in Gaul, Spain, Pannonia, Germany, Arabia, Asia Minor, Portugal and many shrines even in Britain.[26] Tacitus interprets a goddess among the Germanic Suebi as a form of Isis whose symbol (signum) was a ship.[27] Bruce Lincoln regards the identity of this Germanic goddess as "elusive".[28]

The Greek antiquarian Plutarch wrote a treatise on Isis and Osiris,[29] a major source for Imperial theology concerning Isis.[15] Plutarch describes Isis as "a goddess exceptionally wise and a lover of wisdom, to whom, as her name at least seems to indicate, knowledge and understanding are in the highest degree appropriate... ." The statue of Athena in Sais was identified with Isis, and according to Plutarch was inscribed "I am all that has been, and is, and shall be, and my robe no mortal has yet uncovered."[30] At Sais, however, the patron goddess of the ancient cult was Neith, many of whose traits had begun to be attributed to Isis during the Greek occupation.

The Roman writer Apuleius recorded aspects of the cult of Isis in the 2nd century CE, including the Navigium Isidis and the mysteries of Isis in his novel The Golden Ass. The protagonist Lucius prays to Isis as Regina Caeli, "Queen of Heaven":

You see me here, Lucius, in answer to your prayer. I am nature, the universal Mother, mistress of all the elements, primordial child of time, sovereign of all things spiritual, queen of the dead, queen of the ocean, queen also of the immortals, the single manifestation of all gods and goddesses that are, my nod governs the shining heights of Heavens, the wholesome sea breezes. Though I am worshipped in many aspects, known by countless names ... the Egyptians who excel in ancient learning and worship call me by my true name...Queen Isis.[31]

According to Apuleius, these other names include manifestations of the goddess as Ceres, "the original nurturing parent"; Heavenly Venus (Venus Caelestis); the "sister of Phoebus", that is, Diana or Artemis as she is worshipped at Ephesus; or Proserpina (Greek Persephone) as the triple goddess of the underworld.[32] From the middle Imperial period, the title Caelestis, "Heavenly" or "Celestial", is attached to several goddesses embodying aspects of a single, supreme Heavenly Goddess. The Dea Caelestis was identified with the constellation Virgo (the Virgin), who holds the divine balance of justice.

Greco-Roman temples

On the Greek island of Delos a Doric Temple of Isis was built on a high over-looking hill at the beginning of the Roman period to venerate the familiar trinity of Isis, the Alexandrian Serapis and Harpocrates. The creation of this temple is significant as Delos is particularly known as the birthplace of the Greek gods Artemis and Apollo who had temples of their own on the island long before the temple to Isis was built.

In the Roman Empire, a well-preserved example was discovered in Pompeii. The only sanctuary of Isis (fanum Isidis) identified with certainty in Roman Britain is located in Londinium (present-day London).[33]

Late antiquity

The cult of Isis was part of the syncretic tendencies of religion in the Greco-Roman world of late antiquity. The names Isidoros and Isidora in Greek mean "gift of Isis" (similar to "Theodoros", "God's gift").

The sacred image of Isis with the Horus Child in Rome often became a model for the Christian Mary carrying her child Jesus and many of the epithets of the Egyptian Mother of God came to be used for her.[34]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Harry Eilenstein: ISIS: Die Geschichte der Göttin von der Steinzeit bis heute. BOD, Norderstedt 2011, ISBN 3-8423-8189-1, p. 9 – 10.

- ^ a b R.E Witt, Isis in the Ancient World, p. 7, 1997, ISBN 978-0-8018-5642-6

- ^ "Isiopolis essay by M. Isidora Forrest (Isis Magic, M. Isidora Forrest, Abiegnus House, 2013, ISBN 978-1-939112-00-2) on Isis' name origin and pronunciation".

- ^ Veronica Ions, Egyptian Mythology, Paul Hamlyn, 1968, ISBN 978-0-600-02365-4

- ^ Henry Chadwick, The Church in Ancient Society: From Galilee to Gregory the Great, Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 526, ISBN 978-0-19-926577-0

- ^ Loverance, Rowena (2007). Christian Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-674-02479-3

- ^ a b c Maria Münster: Untersuchungen zur Göttin Isis: vom Alten Reich bis zum Ende des Neuen Reiches. Mit hieroglyphischem Textanhang (= Münchner ägyptologische Studien, Vol. 11). Hessling, Berlin 1968, p. 158 – 164.

- ^ Jan Assmann: Tod und Jenseits im Alten Ägypten. Beck, München 2003, ISBN 3-406-49707-1, p. 56 – 59.

- ^ a b Joyce Tyldesley (2011), The Penguin Book of Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt.

- ^ Dijkstra, Jitse H. F. (2008). Philae and the End of Egyptian Religion, pp. 337–348

- ^ "Tyet sign [Egyptian; Abydos, Cemetery D, Tomb 33] (00.4.39) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. 2014-06-02. Retrieved 2014-06-15.

- ^ "Tyet | Define Tyet at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2014-06-15.

- ^ "Red jasper tit amulet of Nefer at The British Museum Images". Bmimages.com. Retrieved 2014-06-15.

- ^ "Isis Nursing Horus". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ a b D.S. Richter, "Plutarch On Isis and Osiris: Text, Cult, and Cultural Appropriation", Transactions of the American Philological Association (2001) 131:191–216

- ^ Mercantante, Anthony S. Who's What in Egyptian Mythology MetroBooks (NY); 2nd edition (March 2002) ISBN 978-1-58663-611-1 p.114

- ^ a b Pinch, Geraldine (August 31, 2002). Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. ABC-CLIO Ltd. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-57607-242-4.

- ^ Griffiths, J. Gwyn. (2002). "Isis". In D. B. Redford (Ed.), The ancient gods speak: A guide to Egyptian religion. p. 169. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Silverman, Ancient Egypt, 135

- ^ Herodotus, Histories. 2.42 and 156.

- ^ R.E Witt, Isis in the Ancient World, 1997, ISBN 0-8018-5642-6

- ^ This is particularly characteristic of Stoic philosophy. See in general Davide Del Bello, Forgotten Paths: Etymology and the Allegorical Mindset (Catholic University of America Press, 2007).

- ^ "Banknotes in circulation: 10 Denars". National Bank of the Republic of Macedonia. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ a b R.E Witt, Isis in the Ancient World, Ch17: "The Goddess Darling of the Roman Emperors", p. 235, 1997, ISBN 0-8018-5642-6

- ^ R.E Witt, Isis in the Ancient World, p.51, 1997, ISBN 0-8018-5642-6

- ^ R.E Witt, Isis in the Ancient World, 1997, ISBN 0-8018-5642-6

- ^ Tacitus, Germania 9.

- ^ Bruce Lincoln, Gods and Demons, Priests and Scholars: Critical Explorations in the History of Religions (University of Chicago Press, 2012), p. 21.

- ^ "Plutarch: Isis and Osiris". Loeb Classical Library.

- ^ Plutarch, translated by Frank Cole Babbitt, Isis and Osiris, 1936, vol. 5 Loeb Classical Library

- ^ Apuleius, Metamorphoses 11.2.

- ^ Stephen Benko, The Virgin Goddess: Studies in the Pagan and Christian roots of Mariology (Brill, 2004), pp. 112–114: see also pp. 31, 51.

- ^ Martin Henig, Religion in Roman Britain (Taylor & Francis, 1984, 2005), p. 100.

- ^ National Geographic Video Mysteries of the Bible: Rivals of Jesus. See 28 min 50s

References

Primary sources

- Ovid, Metamorphoses i.588–747

- Eusebius, Chronicon 32.9–13, 40.7–9, 43.12–16

Secondary sources

- Ian Shaw (2000) The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt

- Rosalie David (1998) Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt

- Lewis Spence (1990) Ancient Egyptian Myths and Legends

- Plutarch, (1936) De Iside et Osiride, edited by Frank C. Babbitt

- Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt

- Ian Shaw & Paul T. Nicholson (1995) The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt

- Holger Kockelmann, Praising the goddess: a comparative and annotated re-edition of six demotic hymns and praises addressed to Isis (Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2008).

- Forrest, M. Isidora (2001). Isis Magic: Cultivating a Relationship with the Goddess of 10,000 Names. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications. p. 624. ISBN 9781567182866.