Liver: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 136: | Line 136: | ||

==Diseases of the liver==<!-- This section is linked from [[George Mason University]] --> |

==Diseases of the liver==<!-- This section is linked from [[George Mason University]] --> |

||

de lever gaat stuk van kutgrappen |

|||

{{main|Liver disease}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Many diseases of the liver are accompanied by [[jaundice]] caused by increased levels of [[bilirubin]] in the system. The bilirubin results from the breakup of the [[hemoglobin]] of dead [[red blood cell]]s; normally, the liver removes bilirubin from the blood and excretes it through bile. |

|||

There are also many pediatric liver diseases, including [[biliary atresia]], [[alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency]], [[alagille syndrome]], [[progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis]], and Langerhans cell histiocytosis to name but a few. |

|||

Liver diseases may be diagnosed by [[liver function tests]], for example, by production of [[acute phase protein]]s. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The liver is the only internal human organ capable of natural [[regeneration (biology)|regeneration]] of lost [[Biological tissue|tissue]]; as little as 25% of a liver can regenerate into a whole liver. |

The liver is the only internal human organ capable of natural [[regeneration (biology)|regeneration]] of lost [[Biological tissue|tissue]]; as little as 25% of a liver can regenerate into a whole liver. |

||

Revision as of 11:11, 23 April 2009

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (June 2008) |

| Liver | |

|---|---|

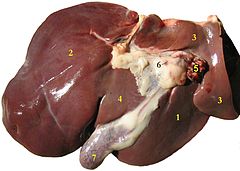

Liver of a sheep: (1) right lobe, (2) left lobe, (3) caudate lobe, (4) quadrate lobe, (5) hepatic artery and portal vein, (6) hepatic lymph nodes, (7) gall bladder. | |

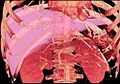

Anterior view of the position of the liver (red) in the human abdomen. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | foregut |

| Vein | hepatic vein, hepatic portal vein |

| Nerve | celiac ganglia, vagus[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | jecur |

| MeSH | D008099 |

| TA98 | A05.8.01.001 |

| TA2 | 3023 |

| FMA | 7197 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The liver is a vital organ present in vertebrates and some other animals; it has a wide range of functions, a few of which are detoxification, protein synthesis, and production of biochemicals necessary for digestion. The liver is necessary for survival; there is currently no way to compensate for the absence of liver function.

The liver plays a major role in metabolism and has a number of functions in the body, including glycogen storage, decomposition of red blood cells, plasma protein synthesis, hormone production, and detoxification. The liver is also the largest gland in the human body. It lies below the diaphragm in the thoracic region of the abdomen. It produces bile, an alkaline compound which aids in digestion, via the emulsification of lipids. It also performs and regulates a wide variety of high-volume biochemical reactions requiring highly specialized tissues.[2]

Medical terms related to the liver often start in hepato- or hepatic from the Greek word for liver, hēpar (ήπαρ).[3]

Anatomy

An adult human liver normally weighs between 1.4-1.6 kg (3.1-3.5 lb),[4] and is a soft, pinkish-brown, triangular organ. Averaging about the size of an American football in adults, it is both the largest internal organ and the largest gland in the human body (not considering the skin).

It is located in the right upper quadrant of the abdominal cavity, resting just below the diaphragm. The liver lies to the right of the stomach and overlies the gallbladder.

Blood flow

The liver receives a dual blood supply consisting of the hepatic portal vein and hepatic arteries. Supplying approximately 75% of the liver's blood supply, the hepatic portal vein carries venous blood drained from the spleen, gastrointestinal tract, and its associated organs. The hepatic arteries supply arterial blood to the liver, accounting for the remainder of its blood flow. Oxygen is provided from both sources; approximately half of the liver's oxygen demand is met by the hepatic portal vein, and half is met by the hepatic arteries.[5]

Biliary flow

The bile produced in the liver is collected in bile canaliculi, which merge to form bile ducts. Within the liver, these ducts are called intrahepatic bile ducts, and once they exit the liver they are considered extrahepatic. The extrahepatic ducts eventually drain into the right and left hepatic ducts, which in turn merge to form the common hepatic duct. The cystic duct from the gallbladder joins with the common hepatic duct to form the common bile duct. The term biliary tree is derived from the arboreal branches of the bile ducts. The intrahepatic bile ducts form the most distant branches of this tree.

Bile can either drain directly into the duodenum via the common bile duct or be temporarily stored in the gallbladder via the cystic duct. The common bile duct and the pancreatic duct enter the duodenum together at the ampulla of Vater.

Surface anatomy

Peritoneal ligaments

Apart from a patch where it connects to the diaphragm (the so-called "bare area"), the liver is covered entirely by visceral peritoneum, a thin, double-layered membrane that reduces friction against other organs. The peritoneum folds back on itself to form the falciform ligament and the right and left triangular ligaments.

These "ligaments" are in no way related to the true anatomic ligaments in joints, and have essentially no functional importance, but they are easily recognizable surface landmarks.

Lobes

Traditional gross anatomy divided the liver into four lobes based on surface features. The falciform ligament is visible on the front (anterior side) of the liver. This divides the liver into a left anatomical lobe, and a right anatomical lobe.

If the liver flipped over, to look at it from behind (the visceral surface), there are two additional lobes between the right and left. These are the caudate lobe (the more superior), and below this the quadrate lobe.

From behind, the lobes are divided up by the ligamentum venosum and ligamentum teres (anything left of these is the left lobe), the transverse fissure (or porta hepatis) divides the caudate from the quadrate lobe, and the right sagittal fossa, which the inferior vena cava runs over, separates these two lobes from the right lobe.

Each of the lobes is made up of lobules, a vein goes from the centre of each lobule which then joins to the hepatic vein to carry blood out from the liver.

On the surface of the lobules there are ducts, veins and arteries that carry fluids to and from them.

Functional anatomy

| Segment* | Couinaud segments |

|---|---|

| Caudate | 1 |

| Lateral | 2, 3 |

| Medial | 4a, 4b |

| Right | 5, 6, 7, 8 |

|

* or lobe in the case of the caudate lobe.

| |

The central area where the common bile duct, hepatic portal vein, and hepatic artery proper enter is the hilum or "porta hepatis". The duct, vein, and artery divide into left and right branches, and the portions of the liver supplied by these branches constitute the functional left and right lobes.

The functional lobes are separated by an imaginary plane joining the gallbladder fossa to the inferior vena cava. The plane separates the liver into the true right and left lobes. The middle hepatic vein also demarcates the true right and left lobes. The right lobe is further divided into an anterior and posterior segment by the right hepatic vein. The left lobe is divided into the medial and lateral segments by the left hepatic vein. The fissure for the ligamentum teres also separates the medial and lateral segments. The medial segment is also called the quadrate lobe. In the widely used Couinaud (or "French") system, the functional lobes are further divided into a total of eight subsegments based on a transverse plane through the bifurcation of the main portal vein. The caudate lobe is a separate structure which receives blood flow from both the right- and left-sided vascular branches.[6][7]

Physiology

The various functions of the liver are carried out by the liver cells or hepatocytes. Currently, there is no artificial organ or device capable of emulating all the functions of the liver[citation needed]. Some functions can be emulated by liver dialysis, an experimental treatment for liver failure.

Synthesis

- A large part of amino acid synthesis

- The liver performs several roles in carbohydrate metabolism:

- Gluconeogenesis (the synthesis of glucose from certain amino acids, lactate or glycerol)

- Glycogenolysis (the breakdown of glycogen into glucose) (muscle tissues can also do this)

- Glycogenesis (the formation of glycogen from glucose)

- The liver is responsible for the mainstay of protein metabolism, synthesis as well as degradation

- The liver also performs several roles in lipid metabolism:

- Cholesterol synthesis

- Lipogenesis, the production of triglycerides (fats).

- The liver produces coagulation factors I (fibrinogen), II (prothrombin), V, VII, IX, X and XI, as well as protein C, protein S and antithrombin.

- In the first trimester fetus, the liver is the main site of red blood cell production. By the 32nd week of gestation, the bone marrow has almost completely taken over that task.

- The liver produces and excretes bile (a greenish liquid) required for emulsifying fats. Some of the bile drains directly into the duodenum, and some is stored in the gallbladder.

- The liver also produces insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), a polypeptide protein hormone that plays an important role in childhood growth and continues to have anabolic effects in adults.

- The liver is a major site of thrombopoietin production. Thrombopoietin is a glycoprotein hormone that regulates the production of platelets by the bone marrow.

Breakdown

- The breakdown of insulin and other hormones

- The liver breaks down hemoglobin, creating metabolites that are added to bile as pigment (bilirubin and biliverdin).

- The liver breaks down toxic substances and most medicinal products in a process called drug metabolism. This sometimes results in toxication, when the metabolite is more toxic than its precursor. Preferably, the toxins are conjugated to avail excretion in bile or urine.

- The liver converts ammonia to urea.

Other functions

- The liver stores a multitude of substances, including glucose (in the form of glycogen), vitamin A (1–2 years' supply), vitamin D (1–4 months' supply), vitamin B12, iron, and copper.

- The liver is responsible for immunological effects- the reticuloendothelial system of the liver contains many immunologically active cells, acting as a 'sieve' for antigens carried to it via the portal system.

- The liver produces albumin, the major osmolar component of blood serum.

Diseases of the liver

de lever gaat stuk van kutgrappen ==Regeneration

The liver is the only internal human organ capable of natural regeneration of lost tissue; as little as 25% of a liver can regenerate into a whole liver.

This is predominantly due to the hepatocytes re-entering the cell cycle. That is, the hepatocytes go from the quiescent G0 phase to the G1 phase and undergo mitosis. This process is activated by the p75 receptors.[8] There is also some evidence of bipotential stem cells, called ovalocytes or hepatic oval cells, which are thought to reside in the canals of Hering. These cells can differentiate into either hepatocytes or cholangiocytes, the latter being the cells that line the bile ducts.

Liver transplantation

Human liver transplants were first performed by Thomas Starzl in the United States and Roy Calne in Cambridge, England in 1963 and 1965 respectively.

Liver transplantation is the only option for those with irreversible liver failure. Most transplants are done for chronic liver diseases leading to cirrhosis, such as chronic hepatitis C, alcoholism, autoimmune hepatitis, and many others. Less commonly, liver transplantation is done for fulminant hepatic failure, in which liver failure occurs over days to weeks.

Liver allografts for transplant usually come from non-living donors who have died from fatal brain injury. Living donor liver transplantation is a technique in which a portion of a living person's liver is removed and used to replace the entire liver of the recipient. This was first performed in 1989 for pediatric liver transplantation. Only 20% of an adult's liver (Couinaud segments 2 and 3) is needed to serve as a liver allograft for an infant or small child.

More recently, adult-to-adult liver transplantation has been done using the donor's right hepatic lobe which amounts to 60% of the liver. Due to the ability of the liver to regenerate, both the donor and recipient end up with normal liver function if all goes well. This procedure is more controversial as it entails performing a much larger operation on the donor, and indeed there have been at least 2 donor deaths out of the first several hundred cases. A recent publication has addressed the problem of donor mortality, and at least 14 cases have been found.[9] The risk of postoperative complications (and death) is far greater in right sided hepatectomy than left sided operations.

With the recent advances of non-invasive imaging, living liver donors usually have to undergo imaging examinations for liver anatomy to decide if the anatomy is feasible for donation. The evaluation is usually performed by multi-detector row computed tomography (MDCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MDCT is good in vascular anatomy and volumetry. MRI is used for biliary tree anatomy. Donors with very unusual vascular anatomy, which makes them unsuitable for donation, could be screened out to avoid unnecessary operations.

-

MDCT image. Arterial anatomy contraindicated for liver donation.

-

MDCT image. Portal venous anatomy contraindicated for liver donation.

-

MDCT image. 3D image created by MDCT can clearly visualize the liver, measure the liver volume, and plan the dissection plane to facilitate the liver transplantation procedure.

Development

Fetal blood supply

In the growing fetus, a major source of blood to the liver is the umbilical vein which supplies nutrients to the growing fetus. The umbilical vein enters the abdomen at the umbilicus, and passes upward along the free margin of the falciform ligament of the liver to the inferior surface of the liver. There it joins with the left branch of the portal vein. The ductus venosus carries blood from the left portal vein to the left hepatic vein and then to the inferior vena cava, allowing placental blood to bypass the liver.

In the fetus, the liver develops throughout normal gestation, and does not perform the normal filtration of the infant liver. The liver does not perform digestive processes because the fetus does not consume meals directly, but receives nourishment from the mother via the placenta. The fetal liver releases some blood stem cells that migrate to the fetal thymus, so initially the lymphocytes, called T-cells, are created from fetal liver stem cells. Once the fetus is delivered, the formation of blood stem cells in infants shifts to the red bone marrow.

After birth, the umbilical vein and ductus venosus are completely obliterated two to five days postpartum; the former becomes the ligamentum teres and the latter becomes the ligamentum venosum. In the disease state of cirrhosis and portal hypertension, the umbilical vein can open up again.

Liver as food

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 561 kJ (134 kcal) |

2.5 g | |

3.7 g | |

21 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 722% 6500 μg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 231% 3 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 94% 15 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 41% 0.7 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 53% 212 μg |

| Vitamin B12 | 1083% 26 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Iron | 128% 23 mg |

| Sodium | 4% 87 mg |

Beef and chicken liver are comparable. | |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[10] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[11] | |

Mammal and bird livers are commonly eaten as food by humans. Liver can be baked, boiled, broiled, fried (often served as liver and onions) or eaten raw (liver sashimi), but is perhaps most commonly made into spreads (examples include liver pâté, foie gras, chopped liver, and leverpostej), or sausages such as Braunschweiger and liverwurst). Liver sausages may also be used as spreads.

Animal livers are rich in iron and Vitamin A, and cod liver oil is commonly used as a dietary supplement. Very high doses of Vitamin A can be toxic; in 1913, Antarctic explorers Douglas Mawson and Xavier Mertz were both poisoned, the latter fatally, from eating husky liver. In the US, the USDA specifies 3000 μg per day as a tolerable upper limit, which amounts to about 50 g of raw pork liver. [12] Poisoning will less likely result from consuming oil-based vitamin A preparations and liver than from consuming water-based and solid preparations.[13]

Cultural allusions

The liver has always been an important symbol in occult physiology. As the largest organ, the one containing the most blood, it was regarded as the darkest, least penetrable part of man's innards. Thus it was considered to contain the secret of fate and was used for fortunetelling. In Plato, and in later physiology, the liver represented the darkest passions, particularly the bloody, smoky ones of wrath, jealousy, and greed which drive men to action. Thus the liver meant the impulsive attachment to life itself.

In Greek mythology, Prometheus was punished by the gods for revealing fire to humans, by being chained to a rock where a vulture (or an eagle) would peck out his liver, which would regenerate overnight. (The liver is the only human internal organ that actually can regenerate itself to a significant extent.)

Many ancient peoples of the Near East and Mediterranean areas practised a type of divination called haruspicy, whereby they tried to obtain information from examining the livers of sheep and other animals.

The Talmud (tractate Berakhot 61b) refers to the liver as the seat of anger, with the gallbladder counteracting this.

In the Persian, Urdu, and Hindi languages, the liver (جگر or जिगर or jigar) refer to the liver in figurative speech to refer to courage and strong feelings, or "their best," e.g. "This Mecca has thrown to you the pieces of its liver!" [15]. The term jan e jigar literally "the strength (power) of my liver" is a term of endearment in Urdu. In Persian slang, jigar is used as an adjective for any object which is desirable, especially women.

The legend of Liver-Eating Johnson says that he would cut out and eat the liver of each man killed after dinner.

In the motion picture The Message, Hind bint Utbah is implied or portrayed eating the liver of Hamza ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib during the Battle of Uhud.

Inuit will not eat the liver of polar bears (a polar bear's liver contains so much Vitamin A as to be poisonous to humans), or seals [16]

Gallery

-

Accessory digestive system.

-

Digestive organs.

-

The liver and the veins in connection with it, of a human embryo, twenty-four or twenty-five days old, as seen from the ventral surface.

-

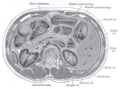

Transverse section through the middle of the first lumbar vertebra, showing the relations of the pancreas.

-

Front of abdomen, showing surface markings for liver, stomach, and great intestine

-

Topography of thoracic and abdominal viscera.

-

View of the superior ("top") surface from Gray's Anatomy (1918)

-

View of the inferior ("bottom") surface from Gray's Anatomy (1918)

-

Human Liver taken from Autopsy

See also

- Artificial liver

- Bile

- Bile canaliculus

- Hepatocyte

- Liver function tests

- Liver shot (martial arts strike)

References

- ^ Template:GeorgiaPhysiology

- ^ Maton, Anthea (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1. OCLC 32308337.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The Greek word "ήπαρ" was derived from hēpaomai (ηπάομαι): to mend, to repair, hence hēpar actually means "repairable", indicating that this organ can regenerate itself spontaneously in the case of lesion.

- ^ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. p. 878. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Benjamin L. Shneider; Sherman, Philip M. (2008). Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disease. Connecticut: PMPH-USA. p. 751. ISBN 1-55009-364-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Three-dimensional Anatomy of the Couinaud Liver Segments". Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ^ "Prof. Dr. Holger Strunk - Homepage". Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ^ Suzuki K, Tanaka M, Watanabe N, Saito S, Nonaka H, Miyajima A (2008). "p75 Neurotrophin receptor is a marker for precursors of stellate cells and portal fibroblasts in mouse fetal liver". Gastroenterology. 135 (1): 270–281.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.075. PMID 18515089.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bramstedt K (2006). "Living liver donor mortality: where do we stand?". Am J Gastrointestinal. 101 (4): 755–9. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00421.x. PMID 16494593.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ A. Aggrawal, Death by Vitamin A

- ^ Myhre et al., "Water-miscible, emulsified, and solid forms of retinol supplements are more toxic than oil-based preparations", Am. J. Clinical Nutrition, 78, 1152 (2003)

- ^ Krishna, Gopi (1970). Kundalini – the evolutionary energy in man. London: Stuart & Watkins. p. 77. SBN 7224 0115 9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ THE GREAT BATTLE OF BADAR (Yaum-e-Furqan)

- ^ Man's best friend? - Student BMJ

Further reading

- The following are standard medical textbooks:

- Eugene R. Schiff, Michael F. Sorrell, Willis C. Maddrey, eds. Schiff's diseases of the liver, 9th ed. Philadelphia : Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2003. ISBN 0-7817-3007-4

- Sheila Sherlock, James Dooley. Diseases of the liver and biliary system, 11th ed. Oxford, UK ; Malden, MA : Blackwell Science. 2002. ISBN 0-632-05582-0

- David Zakim, Thomas D. Boyer. eds. Hepatology: a textbook of liver disease, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders. 2003. ISBN 0-7216-9051-3

- These are for the lay reader or patient:

- Sanjiv Chopra. The Liver Book: A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosis, Treatment, and Recovery, Atria, 2002, ISBN 0-7434-0585-4

- Melissa Palmer. Dr. Melissa Palmer's Guide to Hepatitis and Liver Disease: What You Need to Know, Avery Publishing Group; Revised edition May 24, 2004, ISBN 1-58333-188-3. her webpage.

- Howard J. Worman. The Liver Disorders Sourcebook, McGraw-Hill, 1999, ISBN 0-7373-0090-6. his Columbia University web site, "Diseases of the liver"

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. |

- Information

- UC Berkeley anatomy lecture on the liver

- Electron microscopic images of the liver (Dr. Jastrow's EM-atlas)

- Elevated liver enzymes information

- "It's Dangerous to Ignore Your Liver" by the American Liver Foundation

- "The Liver and its Diseases" — information at h2g2

- Autoimmune immune liver disease

- VIRTUAL Liver - online learning resource