Microeconomics

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

Microeconomics (from Greek prefix mikro- meaning "small") is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms.[1][2][3]

One goal of microeconomics is to analyze the market mechanisms that establish relative prices among goods and services and allocate limited resources among alternative uses. Microeconomics shows conditions under which free markets lead to desirable allocations. It also analyzes market failure, where markets fail to produce efficient results.

Microeconomics stands in contrast to macroeconomics, which involves "the sum total of economic activity, dealing with the issues of growth, inflation, and unemployment and with national policies relating to these issues".[2] Microeconomics also deals with the effects of economic policies (such as changing taxation levels) on the aforementioned aspects of the economy.[4] Particularly in the wake of the Lucas critique, much of modern macroeconomic theory has been built upon 'microfoundations'—i.e. based upon basic assumptions about micro-level behavior.

Assumptions and definitions

Microeconomic theory typically begins with the study of a single rational and utility maximizing individual. To economists, rationality means an individual possesses stable preferences that are both complete and transitive. The technical assumption that preference relations are continuous is needed to ensure the existence of a utility function. Although microeconomic theory can continue without this assumption, it would make comparative statics impossible since there is no guarantee that the resulting utility function would be differentiable.

Microeconomic theory progresses by defining a competitive budget set which is a subset of the consumption set. It is at this point that economists make the technical assumption that preferences are locally non-satiated. Without the assumption of LNS (local non-satiation) there is no guarantee that a rational individual would maximize utility. With the necessary tools and assumptions in place the utility maximization problem (UMP) is developed.

The utility maximization problem is the heart of consumer theory. The utility maximization problem attempts to explain the action axiom by imposing rationality axioms on consumer preferences and then mathematically modeling and analyzing the consequences. The utility maximization problem serves not only as the mathematical foundation of consumer theory but as a metaphysical explanation of it as well. That is, the utility maximization problem is used by economists to not only explain what or how individuals make choices but why individuals make choices as well.

The utility maximization problem is a constrained optimization problem in which an individual seeks to maximize utility subject to a budget constraint. Economists use the extreme value theorem to guarantee that a solution to the utility maximization problem exists. That is, since the budget constraint is both bounded and closed, a solution to the utility maximization problem exists. Economists call the solution to the utility maximization problem a Walrasian demand function or correspondence.

The utility maximization problem has so far been developed by taking consumer tastes (i.e. consumer utility) as the primitive. However, an alternative way to develop microeconomic theory is by taking consumer choice as the primitive. This model of microeconomic theory is referred to as revealed preference theory.

The theory of supply and demand usually assumes that markets are perfectly competitive. This implies that there are many buyers and sellers in the market and none of them have the capacity to significantly influence prices of goods and services. In many real-life transactions, the assumption fails because some individual buyers or sellers have the ability to influence prices. Quite often, a sophisticated analysis is required to understand the demand-supply equation of a good model. However, the theory works well in situations meeting these assumptions.

Mainstream economics does not assume a priori that markets are preferable to other forms of social organization. In fact, much analysis is devoted to cases where market failures lead to resource allocation that is suboptimal and creates deadweight loss. A classic example of suboptimal resource allocation is that of a public good. In such cases, economists may attempt to find policies that avoid waste, either directly by government control, indirectly by regulation that induces market participants to act in a manner consistent with optimal welfare, or by creating "missing markets" to enable efficient trading where none had previously existed.

This is studied in the field of collective action and public choice theory. "Optimal welfare" usually takes on a Paretian norm, which is a mathematical application of the Kaldor–Hicks method. This can diverge from the Utilitarian goal of maximizing utility because it does not consider the distribution of goods between people. Market failure in positive economics (microeconomics) is limited in implications without mixing the belief of the economist and their theory.

The demand for various commodities by individuals is generally thought of as the outcome of a utility-maximizing process, with each individual trying to maximize their own utility under a budget constraint and a given consumption set.

Microeconomic theories are involved with the choices that households and firms make. Some of these microeconomic concepts include elasticity of demand and supply, market structures and utility. Microeconomic looks into the way individuals and businesses behave in coming up with decisions to do with the distribution of rare resources and collaborations between these individuals and the firm. A production possibility frontier illustrates the maximum probable output combinations of two services or goods an economy may realise while all other resources are efficiently and wholly engaged. A production possibility frontier is used to explain the models of opportunity cost, illustrate the effects of economic development and demonstrate the theory of trade-offs.

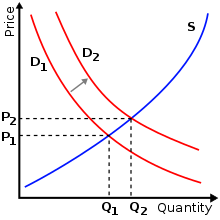

Supply and demand is possibly amongst the most crucial conceptions of economics and it is the pillar of the economy of a market. Demand can be explained as the extent to which a service or a good is desired by users. The amount demanded is the sum of a commodity individuals are ready to purchase at a certain given price. Supply on the other hand refers to how much of a product a market can provide. The supplied quantity is the volume of a particular commodity manufacturers are willing to supply at a certain price. The relationship between demand and supply trigger the forces as a result of the sharing of resources. The law of demand states that when all other influences stay constant the higher the price of a good, the lesser the demand of the given produce. In other word the greater the price the lower the amount needed. The amount of a good bought by customers at a greater price is lower as the price rises the opportunity cost of buying a commodity. People will therefore naturally evade buying a commodity that will need them to sacrifice the use of something else that is more significant to them. Similar to the law of demand, the law of supply reveals the amounts that will be traded at a certain given price. Contrasting the law of demand, the supply relationship gives a rising slope. This means that the bigger the price the greater the quantity in supply. Manufacturers supply more at a high price because selling a quantity at a higher price rises income. Where demand and supply are the same, the economy is held to be at equilibrium. At the point of equilibrium the distribution of goods is at its most effectual because the amount of goods at supply is precisely the same as the volume of goods in demand. Therefore every individual is contented with prevailing state of the economy.

Elasticity is defined as the degree of receptiveness in demand and supply in relation to fluctuations in price. If a curve is more elastic then lesser alterations in price will result to a higher change in quantity used up. If a curve is less elastic it will then cause higher deviations in price to affect a change in amount consumed. Price elasticity of demand is the extent of responsiveness in quantity demanded in relation to price. Utility on the other hand is the amount of contentment resulting from the consumption of a commodity or services at a particular period. Utility is a psychological satisfaction not inherent. It is dependent on the persons own subjective approximate of satisfaction to be acquired from the consumption of a commodity. Utility is further divided into marginal utility, total utility and maximizing utility. Marginal utility refers to the extra utility resulting from the consumption of one extra unit of a commodity, the consumption of the rest of the goods remaining unaffected. Total utility is refers to as the number of units of utility that a consumer gains from consuming a given quantity of a good, service, or activity during a particular time period. The greater a consumers total utility, the larger the customer’s level of consumption. The cost to any firm of producing any output evidently depends upon the physical amounts of real resources. For instance material, labour and machine hours used in production. As the larger output needs a larger amount of resources, the total cost for larger output becomes high. Whereas the smaller output requires the smaller resources. The total cost for smaller output becomes smaller. A company can produce at lower cost when it produces better new techniques to products. Production with traditional and old method implicates high cost. The maximisation of returns includes the use of a definite technique to produce that can facilitate the optimal combination of factors. Production cost is defined as the expenditures by a business in producing a commodity. There are several kinds of cost concepts, these are marginal cost, total cost and average cost. Total is the cost of producing a certain output of the product in question. Total cost can be classified into variable cost and fixed cost. Fixed costs is also known as overhead cost. These are costs which do not differ with output. The costs will be the same whether the output is ten or twenty or a thousand of a product. Fixed costs entails interest on bank loans, depreciation of machinery, insurance charges and rent of factory. Variable costs are also called prime cost. Variable costs differ with alterations in output. The greater the output, the bigger the variable costs. Average cost is the cost of each unit of output and is achieved by dividing the total cost by the level of output. It is further divided into two parts, average fixed cost and average variable cost. Marginal cost is defined as the extra cost incurred by increasing output by one unit. It is the added cost of producing an additional unit of output. Perfect competition is a market structure in which the following characteristics are met. All businesses trade the same commodity, all firms will have a comparatively small market share, all firms are price takers meaning they cannot control the market price of their goods, the industry is characterized by freedom of entry and exit, and buyers have complete information about the product being sold and the prices charged by each firm. Perfect competition is a hypothetical market structure. Under perfect competition there are numerous buyers and sellers and prices reveal supply and demand. Customers will have several substitutes when the commodity they wish to buy quality begins to reduce or if it becomes more expensive. News firms can as well simply enter the market, leading to an extra competition. Monopoly on the other hand is where there is only one supplier in the market. For the reasons of regulation, monopoly power occurs where a single business owns 25% or more of a particular market. Monopolies can form for a number of reasons. For example, government can grant a business monopoly powers, if a firm has exclusive ownership of a limited resource, producers may have patents over designs for instance, giving them rights to trade a good or a service and a merger of two or more firms would create a monopoly. Monopolies have basic characteristics such as, they can maintain super normal returns in the long run, a monopolist with no substitute would be able to develop the greatest monopoly power and with no close substitutes, the monopolist can therefore derive supernormal profits.

In conclusion, microeconomics tries in any way not to explain what ought to happen in a market. Instead it explains what to anticipate if some conditions are altered. For instance, if producers increase the price of a commodity, customers will opt to purchase fewer of a product than before.

Topics

The study of microeconomics involves several "key" areas:

Demand, supply, and equilibrium

Supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a perfectly competitive market. It concludes that in a perfectly competitive market with no externalities, per unit taxes, or price controls, the unit price for a particular good is the price at which the quantity demanded by consumers equals the quantity supplied by producers. This price results in a stable economic equilibrium.

Measurement of elasticities

Elasticity is the measurement of how responsive an economic variable is to a change in another variable. Elasticity can be quantified as the ratio of the percentage change in one variable to the percentage change in another variable, when the later variable has a causal influence on the former. It is a tool for measuring the responsiveness of a variable, or of the function that determines it, to changes in causative variables in unitless ways. Frequently used elasticities include price elasticity of demand, price elasticity of supply, income elasticity of demand, elasticity of substitution between factors of production and elasticity of intertemporal substitution.

Consumer demand theory

Consumer demand theory relates preferences for the consumption of both goods and services to the consumption expenditures; ultimately, this relationship between preferences and consumption expenditures is used to relate preferences to consumer demand curves. The link between personal preferences, consumption and the demand curve is one of the most closely studied relations in economics. It is a way of analyzing how consumers may achieve equilibrium between preferences and expenditures by maximizing utility subject to consumer budget constraints.

Theory of production

Production theory is the study of production, or the economic process of converting inputs into outputs. Production uses resources to create a good or service that is suitable for use, gift-giving in a gift economy, or exchange in a market economy. This can include manufacturing, storing, shipping, and packaging. Some economists define production broadly as all economic activity other than consumption. They see every commercial activity other than the final purchase as some form of production.

Costs of production

The cost-of-production theory of value states that the price of an object or condition is determined by the sum of the cost of the resources that went into making it. The cost can comprise any of the factors of production: labour, capital, land. Technology can be viewed either as a form of fixed capital (ex:plant) or circulating capital (ex:intermediate goods).

Perfect competition

Perfect competition describes markets such that no participants are large enough to have the market power to set the price of a homogeneous product. A good example would be that of digital marketplaces, such as eBay, on which many different sellers sell similar products to many different buyers.

Benefits of Perfect Competition- All the knowledge such as price and information pertaining goods is equally dispersed among all buyers and sellers. As there are no barriers to enter into the market, monopoly does not usually occur. As all goods and products are same, advertisement is not required and it helps save the advertisement cost. In perfect competition products are identical.

Monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek monos μόνος (alone or single) + polein πωλεῖν (to sell)) exists when a single company is the only supplier of a particular commodity.

Benefits of Monopoly Market- Prices in monopoly market are stable as there is only one firm and so there is no competition. Due to the absence of competition there are high profits and leads to high number of sales monopoly firms tend to receive super profits from their operations.

Oligopoly

An oligopoly is a market form in which a market or industry is dominated by a small number of sellers (oligopolists). Oligopolies can create the incentive for firms to engage in collusion and form cartels that reduce competition leading to higher prices for consumers and less overall market output.[5]

Benefits of oligopoly market – As there is less competition in the firm, it tends to have massive profit.It is also able to easily compare prices forces these companies to keep their prices in competition with the other companies involved in the market.Each company scrambles to come out with latest and greatest thing in order to sway consumers to go with their company over a different one.

Market structure

The market structure can have several types of interacting market systems. Different forms of markets are a feature of capitalism, and advocates of socialism often criticize markets and aim to substitute markets with economic planning to varying degrees. Competition is the regulatory mechanism of the market system. Market structures may include:

- Monopolistic competition is a type of imperfect competition such that many producers sell products that are differentiated from one another (e.g. by branding or quality) and hence are not perfect substitutes.

- Oligopoly, in which a market is run by a small number of firms that together control the majority of the market share.

- Duopoly, a special case of an oligopoly, with only two firms. Game theory can elucidate behavior in duopolies and oligopolies.[6]

- Monopsony, when there is only one buyer in a market.

- Oligopsony, a market where many sellers can be present but meet only a few buyers.

- Monopoly, where there is only one provider of a product or service.

- Natural monopoly, a monopoly in which economies of scale cause efficiency to increase continuously with the size of the firm. A firm becomes a natural monopoly if it succeeds in serving the entire market demand at a lower cost than any combination of two or more smaller, more specialized firms.

- Perfect competition, a theoretical market structure that features no barriers to entry, an unlimited number of producers and consumers, and a perfectly elastic demand curve.

Examples of markets include but are not limited to: commodity markets, insurance markets, bond markets, energy markets, flea markets, debt markets, stock markets, online auctions, media exchange markets, and the real-estate market.

Game theory

Game theory is a major method used in mathematical economics and business for modeling competing behaviors of interacting agents. The term "game" here implies the study of any strategic interaction between people. Applications include a wide array of economic phenomena and approaches, such as auctions, bargaining, mergers & acquisitions pricing, fair division, duopolies, oligopolies, social network formation, agent-based computational economics, general equilibrium, mechanism design,and voting systems, and across such broad areas as experimental economics, behavioral economics, information economics, industrial organization, and political economy.

Labour economics

Labour economics seeks to understand the functioning and dynamics of the markets for wage labour. Labour markets function through the interaction of workers and employers. Labour economics looks at the suppliers of labour services (workers), the demands of labour services (employers), and attempts to understand the resulting pattern of wages, employment, and income. In economics, labour is a measure of the work done by human beings. It is conventionally contrasted with such other factors of production as land and capital. There are theories which have developed a concept called human capital (referring to the skills that workers possess, not necessarily their actual work), although there are also counter posing macro-economic system theories that think human capital is a contradiction in terms.

Welfare economics

Welfare economics is a branch of economics that uses microeconomics techniques to evaluate well-being from allocation of productive factors as to desirability and economic efficiency within an economy, often relative to competitive general equilibrium.[7] It analyzes social welfare, however measured, in terms of economic activities of the individuals that compose the theoretical society considered. Accordingly, individuals, with associated economic activities, are the basic units for aggregating to social welfare, whether of a group, a community, or a society, and there is no "social welfare" apart from the "welfare" associated with its individual units.

Economics of information

Information economics or the economics of information is a branch of microeconomic theory that studies how information and information systems affect an economy and economic decisions. Information has special characteristics. It is easy to create but hard to trust. It is easy to spread but hard to control. It influences many decisions. These special characteristics (as compared with other types of goods) complicate many standard economic theories.[8]

Opportunity cost

Opportunity cost of an activity (or goods) is equal to the best next alternative uses/forgone. Although opportunity cost can be hard to quantify, the effect of opportunity cost is universal and very real on the individual level. In fact, this principle applies to all decisions, not just economic ones.

Opportunity cost is one way to measure the cost of something. Rather than merely identifying and adding the costs of a project, one may also identify the next best alternative way to spend the same amount of money. The forgone profit of this next best alternative is the opportunity cost of the original choice. A common example is a farmer that chooses to farm their land rather than rent it to neighbors, wherein the opportunity cost is the forgone profit from renting. In this case, the farmer may expect to generate more profit alone. This kind of reasoning is a very important part of the calculation of discount rates in discounted cash flow investment valuation methodologies. Similarly, the opportunity cost of attending university is the lost wages a student could have earned in the workforce, rather than the cost of tuition, books, and other requisite items (whose sum makes up the total cost of attendance).

Note that opportunity cost is not the sum of the available alternatives, but rather the benefit of the single, best alternative. Possible opportunity costs of a city's decision to build a hospital on its vacant land are the loss of the land for a sporting center, or the inability to use the land for a parking lot, or the money that could have been made from selling the land, or the loss of any of the various other possible uses — but not all of these in aggregate. The true opportunity cost would be the forgone profit of the most lucrative of those listed.

One question that arises here is how to determine a money value for each alternative to facilitate comparison and assess opportunity cost, which may be more or less difficult depending on the things we are trying to compare. For example, many decisions involve environmental impacts whose monetary value is difficult to assess because of scientific uncertainty. Valuing a human life or the economic impact of an Arctic oil spill involves making subjective choices with ethical implications.

It is imperative to understand that no decision on allocating time is free. No matter what one chooses to do, they are always giving something up in return. An example of opportunity cost is deciding between going to a concert and doing homework. If one decides to go the concert, then they are giving up valuable time to study, but if they choose to do homework then the cost is giving up the concert. Any decision in allocating capital is likewise: there is an opportunity cost of capital, or a hurdle rate, defined as the expected rate one could get by investing in similar projects on the open market. Opportunity cost is vital in understanding microeconomics and decisions that are made.

Applied

Applied microeconomics includes a range of specialized areas of study, many of which draw on methods from other fields. Industrial organization examines topics such as the entry and exit of firms, innovation, and the role of trademarks. Labor economics examines wages, employment, and labor market dynamics. Financial economics examines topics such as the structure of optimal portfolios, the rate of return to capital, econometric analysis of security returns, and corporate financial behavior. Public economics examines the design of government tax and expenditure policies and economic effects of these policies (e.g., social insurance programs). Political economy examines the role of political institutions in determining policy outcomes. Health economics examines the organization of health care systems, including the role of the health care workforce and health insurance programs. Education economics examines the organization of education provision and its implication for efficiency and equity, including the effects of education on productivity. Urban economics, which examines the challenges faced by cities, such as sprawl, air and water pollution, traffic congestion, and poverty, draws on the fields of urban geography and sociology. Law and economics applies microeconomic principles to the selection and enforcement of competing legal regimes and their relative efficiencies. Economic history examines the evolution of the economy and economic institutions, using methods and techniques from the fields of economics, history, geography, sociology, psychology, and political science.

References

- ^ Marchant, Mary A.; Snell, William M. "Macroeconomic and International Policy Terms" (PDF). University of Kentucky. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ a b "Economics Glossary". Monroe County Women's Disability Network. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Social Studies Standards Glossary". New Mexico Public Education Department. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Glossary". ECON100. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ http://www.ftc.gov/bc/edu/pubs/consumer/general/zgen01.shtm

- ^

"Oligopoly/Duopoly and Game Theory". AP Microeconomics Review. 2017. Retrieved 2017-06-11.

Game theory is the main way economists [sic] understands the behavior of firms within this market structure.

- ^ Deardorff's Glossary of International Economics (2006). "Welfare economics."

- ^ • Beth Allen, 1990. "Information as an Economic Commodity," American Economic Review, 80(2), pp. 268–273.

• Kenneth J. Arrow, 1999. "Information and the Organization of Industry," ch. 1, in Graciela Chichilnisky Markets, Information, and Uncertainty. Cambridge University Press, pp. 20–21.

• _____, 1996. "The Economics of Information: An Exposition," Empirica, 23(2), pp. 119–128.

• _____, 1984. Collected Papers of Kenneth J. Arrow, v. 4, The Economics of Information. Description and chapter-preview links.

• Jean-Jacques Laffont, 1989. The Economics of Uncertainty and Information, MIT Press. Description Archived 2012-01-25 at the Wayback Machine and chapter-preview links.

Further reading

- Bade, Robin; Michael Parkin (2001). Foundations of Microeconomics. Addison Wesley Paperback 1st Edition.

- Template:Cite article

- Bouman, John: Principles of Microeconomics – free fully comprehensive Principles of Microeconomics and Macroeconomics texts. Columbia, Maryland, 2011

- Colander, David. Microeconomics. McGraw-Hill Paperback, 7th Edition: 2008.

- Dunne, Timothy; J. Bradford Jensen; Mark J. Roberts (2009). Producer Dynamics: New Evidence from Micro Data. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-17256-9.

- Eaton, B. Curtis; Eaton, Diane F.; and Douglas W. Allen. Microeconomics. Prentice Hall, 5th Edition: 2002.

- Frank, Robert H.; Microeconomics and Behavior. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 6th Edition: 2006.

- Friedman, Milton. Price Theory. Aldine Transaction: 1976

- Hagendorf, Klaus: Labour Values and the Theory of the Firm. Part I: The Competitive Firm. Paris: EURODOS; 2009.

- Harnerger, Arnold C. (2008). "Microeconomics". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0-86597-665-8. OCLC 237794267.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Hicks, John R. Value and Capital. Clarendon Press. [1939] 1946, 2nd ed.

- Hirshleifer, Jack., Glazer, Amihai, and Hirshleifer, David, Price theory and applications: Decisions, markets, and information. Cambridge University Press, 7th Edition: 2005.

- Jehle, Geoffrey A.; and Philip J. Reny. Advanced Microeconomic Theory. Addison Wesley Paperback, 2nd Edition: 2000.

- Katz, Michael L.; and Harvey S. Rosen. Microeconomics. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 3rd Edition: 1997.

- Kreps, David M. A Course in Microeconomic Theory. Princeton University Press: 1990

- Landsburg, Steven. Price Theory and Applications. South-Western College Pub, 5th Edition: 2001.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory. Principles of Microeconomics. South-Western Pub, 2nd Edition: 2000.

- Mas-Colell, Andreu; Whinston, Michael D.; and Jerry R. Green. Microeconomic Theory. Oxford University Press, US: 1995.

- McGuigan, James R.; Moyer, R. Charles; and Frederick H. Harris. Managerial Economics: Applications, Strategy and Tactics. South-Western Educational Publishing, 9th Edition: 2001.

- Nicholson, Walter. Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Extensions. South-Western College Pub, 8th Edition: 2001.

- Perloff, Jeffrey M. Microeconomics. Pearson – Addison Wesley, 4th Edition: 2007.

- Perloff, Jeffrey M. Microeconomics: Theory and Applications with Calculus. Pearson – Addison Wesley, 1st Edition: 2007

- Pindyck, Robert S.; and Daniel L. Rubinfeld. Microeconomics. Prentice Hall, 7th Edition: 2008.

- Ruffin, Roy J.; and Paul R. Gregory. Principles of Microeconomics. Addison Wesley, 7th Edition: 2000.

- Varian, Hal R. (1987). "microeconomics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 461–63.

- Varian, Hal R. Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach. W. W. Norton & Company, 8th Edition: 2009.

- Varian, Hal R. Microeconomic Analysis. W. W. Norton & Company, 3rd Edition: 1992.