Motorola 68000

| Designer | Motorola |

|---|---|

| Bits | 16/32-bit |

| Introduced | 1979 |

| Design | CISC |

| Branching | Condition code |

| Endianness | Big |

| Registers | |

| General-purpose | 8 × 32-bit + 7 address registers also usable for most operations + stack pointer |

| Performance | |

|---|---|

| Data width | 16 |

| Address width | 24 |

| Architecture and classification | |

| Instructions | 56 |

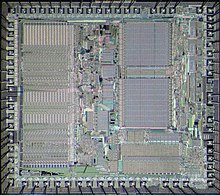

The Motorola 68000 ("'sixty-eight-thousand'"; also called the m68k or Motorola 68k, "sixty-eight-kay") is a 16/32-bit CISC microprocessor, which implements a 32-bit instruction set, with 32-bit registers and 32-bit internal data bus, but with a 16-bit main ALU and a 16-bit external data bus,[1] designed and marketed by Motorola Semiconductor Products Sector (later Freescale Semiconductor, now NXP). Introduced in 1979 with HMOS technology as the first member of the successful 32-bit m68k family of microprocessors, it is generally software forward-compatible with the rest of the line despite being limited to a 16-bit wide external bus.[2] After 38 years in production, the 68000 architecture is still in use.

History

The 68000 grew out of the MACSS (Motorola Advanced Computer System on Silicon) project, begun in 1976 to develop an entirely new architecture without backward compatibility. It would be a higher-power sibling complementing the existing 8-bit 6800 line rather than a compatible successor. In the end, the 68000 did retain a bus protocol compatibility mode for existing 6800 peripheral devices, and a version with an 8-bit data bus was produced. However, the designers mainly focused on the future, or forward compatibility, which gave the 68000 design a head start against later 32-bit instruction set architectures. For instance, the CPU registers are 32 bits wide, though few self-contained structures in the processor itself operate on 32 bits at a time. The MACSS team drew heavily on the influence of minicomputer processor design, such as the PDP-11 and VAX systems, which were similarly microcode-based.

In the mid 1970s, the 8-bit microprocessor manufacturers raced to introduce the 16-bit generation. National Semiconductor had been first with its IMP-16 and PACE processors in 1973–1975, but these had issues with speed. Intel had worked on their advanced 16/32-bit Intel iAPX 432 (alias 8800) since 1975 and their Intel 8086 since 1976 (it was introduced in 1978 but became really widespread in the form of the almost identical 8088 in the IBM PC a few years later). Arriving late to the 16-bit arena afforded the new processor more transistors (roughly 40,000 active versus 20,000 active in the 8086), 32-bit macroinstructions, and acclaimed general ease of use.

The original MC68000 was fabricated using an HMOS process with a 3.5 µm feature size. Formally introduced in September 1979,[3] Initial samples were released in February 1980, with production chips available over the counter in November.[4] Initial speed grades were 4, 6, and 8 MHz. 10 MHz chips became available during 1981[citation needed], and 12.5 MHz chips by June 1982.[4] The 16.67 MHz "12F" version of the MC68000, the fastest version of the original HMOS chip, was not produced until the late 1980s.

The 68k instruction set was particularly well suited to implement Unix,[5] and the 68000 became the dominant CPU for Unix-based workstations including Sun workstations and Apollo/Domain workstations, and also was used for mass-market computers such as the Apple Lisa, Macintosh, Amiga, and Atari ST. The 68000 was used in Microsoft Xenix systems, as well as an early NetWare Unix-based Server. The 68000 was used in the first generation of desktop laser printers, including the original Apple Inc. LaserWriter and the HP LaserJet. In 1982, the 68000 received an update to its ISA allowing it to support virtual memory and to conform to the Popek and Goldberg virtualization requirements. The updated chip was called the 68010. A further extended version, which exposed 31 bits of the address bus, was also produced in small quantities as the 68012.

To support lower-cost systems and control applications with smaller memory sizes, Motorola introduced the 8-bit compatible MC68008, also in 1982. This was a 68000 with an 8-bit data bus and a smaller (20-bit) address bus. After 1982, Motorola devoted more attention to the 68020 and 88000 projects.

Second-sourcing

Several other companies were second-source manufacturers of the HMOS 68000. These included Hitachi (HD68000), who shrank the feature size to 2.7 µm for their 12.5 MHz version,[4] Mostek (MK68000), Rockwell (R68000), Signetics (SCN68000), Thomson/SGS-Thomson (originally EF68000 and later TS68000), and Toshiba (TMP68000). Toshiba was also a second-source maker of the CMOS 68HC000 (TMP68HC000). Encrypted variants of the 68000, being the Hitachi FD1089 and FD1094 store decryption keys for opcodes and opcode data in battery-backed memory, was used in certain Sega arcade systems including System 16 to prevent piracy and illegal bootleg games.[6]

CMOS versions

The 68HC000, the first CMOS version of the 68000, was designed by Hitachi and jointly introduced in 1985.[7] Motorola's version was called the MC68HC000, while Hitachi's was the HD68HC000. The 68HC000 was eventually offered at speeds of 8–20 MHz. Except for using CMOS circuitry, it behaved identically to the HMOS MC68000, but the change to CMOS greatly reduced its power consumption. The original HMOS MC68000 consumed around 1.35 watts at an ambient temperature of 25 °C, regardless of clock speed, while the MC68HC000 consumed only 0.13 watts at 8 MHz and 0.38 watts at 20 MHz. (Unlike CMOS circuits, HMOS still draws power when idle, so power consumption varies little with clock rate.) Apple selected the 68HC000 for use in the Macintosh Portable.

Motorola replaced the MC68008 with the MC68HC001 in 1990.[8] This chip resembled the 68HC000 in most respects, but its data bus could operate in either 16-bit or 8-bit mode, depending on the value of an input pin at reset. Thus, like the 68008, it could be used in systems with cheaper 8-bit memories.

The later evolution of the 68000 focused on more modern embedded control applications and on-chip peripherals. The 68EC000 chip and SCM68000 core expanded the address bus to 32 bits, removed the M6800 peripheral bus, and excluded the MOVE from SR instruction from user mode programs.[9] In 1996, Motorola updated the standalone core with fully static circuitry, drawing only 2 µW in low-power mode, calling it the MC68SEC000.[10]

Motorola ceased production of the HMOS MC68000 and MC68008 in 1996,[11] but its spin-off company Freescale Semiconductor was still producing the MC68HC000, MC68HC001, MC68EC000, and MC68SEC000, as well as the MC68302 and MC68306 microcontrollers and later versions of the DragonBall family. The 68000's architectural descendants, the 680x0, CPU32, and Coldfire families, were also still in production. More recently, with the Sendai fab closure, all 68HC000, 68020, 68030, and 68882 parts have been discontinued, leaving only the 68SEC000 in production.[12]

As a microcontroller core

After being succeeded by "true" 32-bit microprocessors, the 68000 was used as the core of many microcontrollers. In 1989, Motorola introduced the MC68302 communications processor.[13]

Applications

At its introduction, the 68000 was first used in high-priced systems, including multiuser microcomputers like the WICAT 150,[14] early Alpha Microsystems computers, Sage II / IV, Tandy TRS-80 Model 16, and Fortune 32:16; single-user workstations such as Hewlett-Packard's HP 9000 Series 200 systems, the first Apollo/Domain systems, Sun Microsystems' Sun-1, and the Corvus Concept; and graphics terminals like Digital Equipment Corporation's VAXstation 100 and Silicon Graphics' IRIS 1000 and 1200. Unix systems rapidly moved to the more capable later generations of the 68k line, which remained popular in that market throughout the 1980s.

By the mid-1980s, falling production cost made the 68000 viable for use in personal and home computers, starting with the Apple Lisa and Macintosh, and followed by the Commodore Amiga, Atari ST, and Sharp X68000. On the other hand, the Sinclair QL microcomputer was the most commercially important utilisation of the 68008, along with its derivatives, such as the ICL One Per Desk business terminal. Helix Systems (in Missouri, United States) designed an extension to the SWTPC SS-50 bus, the SS-64, and produced systems built around the 68008 processor.

While the adoption of RISC and x86 displaced the 68000 series as desktop/workstation CPU, the processor found substantial use in embedded applications. By the early 1980s, quantities of 68000 CPUs could be purchased for less than 30 USD per part.

Video game manufacturers used the 68000 as the backbone of many arcade games and home game consoles: Atari's Food Fight, from 1982, was one of the first 68000-based arcade games. Others included Sega's System 16, Capcom's CP System and CPS-2, and SNK's Neo Geo. By the late 1980s, the 68000 was inexpensive enough to power home game consoles, such as Sega's Mega Drive (Genesis) console and also the Sega CD attachment for it (A Sega CD system has three CPUs, two of them 68000s). The 1993 multi-processor Atari Jaguar console used a 68000 as a support chip, although some developers used it as the primary processor due to familiarity. The 1994 multi-processor Sega Saturn console used the 68000 as a sound co-processor (much as the Mega Drive/Genesis uses the Z80 as a co-processor for sound and/or other purposes).

Certain arcade games (such as Steel Gunner and others based on Namco System 2) use a dual 68000 CPU configuration,[15] and systems with a triple 68000 CPU configuration also exist (such as Galaxy Force and others based on the Sega Y Board),[16] along with a quad 68000 CPU configuration, which has been used by Jaleco (one 68000 for sound has a lower clock rate compared to the other 68000 CPUs)[17] for games such as Big Run and Cisco Heat; a fifth 68000 (at a different clock rate compared to the other 68000 CPUs) was additionally used in the Jaleco arcade game Wild Pilot for I/O processing.[18]

The 68000 also saw great success as an embedded controller. As early as 1981, laser printers such as the Imagen Imprint-10 were controlled by external boards equipped with the 68000. The first HP LaserJet—introduced in 1984—came with a built-in 8 MHz 68000. Other printer manufacturers adopted the 68000, including Apple with its introduction of the LaserWriter in 1985, the first PostScript laser printer. The 68000 continued to be widely used in printers throughout the rest of the 1980s, persisting well into the 1990s in low-end printers.

The 68000 also saw success in the field of industrial control systems. Among the systems benefited from having a 68000 or derivative as their microprocessor were families of programmable logic controllers (PLCs) manufactured by Allen-Bradley, Texas Instruments and subsequently, following the acquisition of that division of TI, by Siemens. Users of such systems do not accept product obsolescence at the same rate as domestic users, and it is entirely likely that despite having been installed over 20 years ago, many 68000-based controllers will continue in reliable service well into the 21st century.

In a number of digital oscilloscopes from the 80s,[19] the 68000 has been used as a waveform display processor; some models including the LeCroy 9400/9400A[20] also use the 68000 as a waveform math processor (including addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division of two waveforms/references/waveform memories), and some digital oscilloscopes using the 68000 (including the 9400/9400A) can also perform FFT functions on a waveform.

The 683XX microcontrollers, based on the 68000 architecture, are used in networking and telecom equipment, television set-top boxes, laboratory and medical instruments, and even handheld calculators. The MC68302 and its derivatives have been used in many telecom products from Cisco, 3com, Ascend, Marconi, Cyclades and others. Past models of the Palm PDAs and the Handspring Visor used the DragonBall, a derivative of the 68000. AlphaSmart uses the DragonBall family in later versions of its portable word processors. Texas Instruments uses the 68000 in its high-end graphing calculators, the TI-89 and TI-92 series and Voyage 200. Early versions of these used a specialized microcontroller with a static 68EC000 core; later versions use a standard MC68SEC000 processor.

A modified version of the 68000 formed the basis of the IBM XT/370 hardware emulator of the System 370 processor.

Architecture

| Motorola 68000 registers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Address bus

The 68000 has a 24-bit external address bus and two byte-select signals "replaced" A0. These 24 lines can therefore address 16 MB of physical memory with byte resolution. Address storage and computation uses 32 bits internally; however, the 8 high-order address bits are ignored due to the physical lack of device pins. This allows it to run software written for a logically flat 32-bit address space, while accessing only a 24-bit physical address space. Motorola's intent with the internal 32-bit address space was forward compatibility, making it feasible to write 68000 software that would take full advantage of later 32-bit implementations of the 68000 instruction set.[2]

However, this did not prevent programmers from writing forward incompatible software. "24-bit" software that discarded the upper address byte, or used it for purposes other than addressing, could fail on 32-bit 68000 implementations. For example, early (pre-7.0) versions of Apple's Mac OS used the high byte of memory-block master pointers to hold flags such as locked and purgeable. Later versions of the OS moved the flags to a nearby location, and Apple began shipping computers which had "32-bit clean" ROMs beginning with the release of the 1989 Mac IIci.

The 68000 family stores multi-byte integers in memory in big-endian order.

Internal registers

The CPU has eight 32-bit general-purpose data registers (D0-D7), and eight address registers (A0-A7). The last address register is the stack pointer, and assemblers accept the label SP as equivalent to A7. This was a good number of registers at the time in many ways. It was small enough to allow the 68000 to respond quickly to interrupts (even in the worst case where all 8 data registers D0–D7 and 7 address registers A0–A6 needed to be saved, 15 registers in total), and yet large enough to make most calculations fast, because they could be done entirely within the processor without keeping any partial results in memory. (Note that an exception routine in supervisor mode can also save the user stack pointer A7, which would total 8 address registers. However, the dual stack pointer (A7 and supervisor-mode A7') design of the 68000 makes this normally unnecessary, except when a task switch is performed in a multitasking system.)

Having two types of registers was mildly annoying at times, but not hard to use in practice. Reportedly[citation needed], it allowed the CPU designers to achieve a higher degree of parallelism, by using an auxiliary execution unit for the address registers.

Status register

The 68000 comparison, arithmetic, and logic operations sets bit flags in a status register to record their results for use by later conditional jumps. The bit flags are "zero" (Z), "carry" (C), "overflow" (V), "extend" (X), and "negative" (N). The "extend" (X) flag deserves special mention, because it is separate from the carry flag. This permits the extra bit from arithmetic, logic, and shift operations to be separated from the carry for flow-of-control and linkage.

Instruction set

The designers attempted to make the assembly language orthogonal. That is, instructions are divided into operations and address modes, and almost all address modes are available for almost all instructions. There are 56 instructions and a minimum instruction size of 16 bits. Many instructions and addressing modes are longer to include additional address or mode bits.

Privilege levels

The CPU, and later the whole family, implements two levels of privilege. User mode gives access to everything except privileged instructions such as interrupt level controls.[21] Supervisor privilege gives access to everything. An interrupt always becomes supervisory. The supervisor bit is stored in the status register, and is visible to user programs.[21]

An advantage of this system is that the supervisor level has a separate stack pointer. This permits a multitasking system to use very small stacks for tasks, because the designers do not have to allocate the memory required to hold the stack frames of a maximum stack-up of interrupts.

Interrupts

The CPU recognizes seven interrupt levels. Levels 1 through 5 are strictly prioritized. That is, a higher-numbered interrupt can always interrupt a lower-numbered interrupt. In the status register, a privileged instruction allows one to set the current minimum interrupt level, blocking lower or equal priority interrupts. For example, if the interrupt level in the status register is set to 3, higher levels from 4 to 7 can cause an exception. Level 7 is a level triggered Non-maskable interrupt (NMI). Level 1 can be interrupted by any higher level. Level 0 means no interrupt. The level is stored in the status register, and is visible to user-level programs.

Hardware interrupts are signalled to the CPU using three inputs that encode the highest pending interrupt priority. A separate Encoder is usually required to encode the interrupts, though for systems that do not require more than three hardware interrupts it is possible to connect the interrupt signals directly to the encoded inputs at the cost of additional software complexity. The interrupt controller can be as simple as a 74LS148 priority encoder, or may be part of a VLSI peripheral chip such as the MC68901 Multi-Function Peripheral (used in the Atari ST range of computers and Sharp X68000), which also provided a UART, timer, and parallel I/O.

The "exception table" (interrupt vector table interrupt vector addresses) is fixed at addresses 0 through 1023, permitting 256 32-bit vectors. The first vector (RESET) consists of 2 vectors, namely the starting stack address, and the starting code address. Vectors 3 through 15 are used to report various errors: bus error, address error, illegal instruction, zero division, CHK and CHK2 vector, privilege violation (to block privilege escalation), and some reserved vectors that became line 1010 emulator, line 1111 emulator, and hardware breakpoint. Vector 24 starts the real interrupts: spurious interrupt (no hardware acknowledgement), and level 1 through level 7 autovectors, then the 16 TRAP vectors, then some more reserved vectors, then the user defined vectors.

Since at a minimum the starting code address vector must always be valid on reset, systems commonly included some nonvolatile memory (e.g. ROM) starting at address zero to contain the vectors and bootstrap code. However, for a general purpose system it is desirable for the operating system to be able to change the vectors at runtime. This was often accomplished by either pointing the vectors in ROM to a jump table in RAM, or through use of bank switching to allow the ROM to be replaced by RAM at runtime.

The 68000 does not meet the Popek and Goldberg virtualization requirements for full processor virtualization because it has a single unprivileged instruction "MOVE from SR", which allows user-mode software read-only access to a small amount of privileged state.

The 68000 is also unable to easily support virtual memory, which requires the ability to trap and recover from a failed memory access. The 68000 does provide a bus error exception which can be used to trap, but it does not save enough processor state to resume the faulted instruction once the operating system has handled the exception. Several companies did succeed in making 68000-based Unix workstations with virtual memory that worked by using two 68000 chips running in parallel on different phased clocks. When the "leading" 68000 encountered a bad memory access, extra hardware would interrupt the "main" 68000 to prevent it from also encountering the bad memory access. This interrupt routine would handle the virtual memory functions and restart the "leading" 68000 in the correct state to continue properly synchronized operation when the "main" 68000 returned from the interrupt.

These problems were fixed in the next major revision of the 68k architecture, with the release of the MC68010. The Bus Error and Address Error exceptions push a large amount of internal state onto the supervisor stack in order to facilitate recovery, and the MOVE from SR instruction was made privileged. A new unprivileged "MOVE from CCR" instruction is provided for use in its place by user mode software; an operating system can trap and emulate user-mode MOVE from SR instructions if desired.

Instruction set details

The standard addressing modes are:

- Register direct

- data register, e.g. "D0"

- address register, e.g. "A0"

- Register indirect

- Simple address, e.g. (A0)

- Address with post-increment, e.g. (A0)+

- Address with pre-decrement, e.g. -(A0)

- Address with a 16-bit signed offset, e.g. 16(A0)

- Register indirect with index register & 8-bit signed offset e.g. 8(A0, D0) or 8(A0, A1)

- Note that for (A0)+ and -(A0), the actual increment or decrement value is dependent on the operand size: a byte access increments the address register by 1, a word by 2, and a long by 4.

- PC (program counter) relative with displacement

- Relative 16-bit signed offset, e.g. 16(PC). This mode was very useful for position-independent code.

- Relative with 8-bit signed offset with index, e.g. 8(PC, D2)

- Absolute memory location

- Either a number, e.g. "$4000", or a symbolic name translated by the assembler

- Most 68000 assemblers used the "$" symbol for hexadecimal, instead of "0x" or a trailing H.

- There were 16 and 32-bit versions of this addressing mode

- Immediate mode

- Data stored in the instruction, e.g. "#400"

- Quick immediate mode

- 3-bit unsigned (or 8-bit signed with moveq) with value stored in opcode

- In addq and subq, 0 is the equivalent to 8

- e.g. moveq #0,d0 was quicker than clr.l d0 (though both made d0 equal 0)

Plus: access to the status register, and, in later models, other special registers.

Most instructions have dot-letter suffixes, permitting operations to occur on 8-bit bytes (".b"), 16-bit words (".w"), and 32-bit longs (".l").

Like many CPUs of its era the cycle timing of some instructions varied depending on the source operand(s). For example, the unsigned multiply instruction takes (38+2n) clock cycles to complete where 'n' is equal to the number of bits set in the operand.[22] To create a function that took a fixed cycle count required the addition of extra code after the multiply instruction. This would typically consume extra cycles for each bit that wasn't set in the original multiplication operand.

Most instructions are dyadic, that is, the operation has a source, and a destination, and the destination is changed. Notable instructions were:

- Arithmetic: ADD, SUB, MULU (unsigned multiply), MULS (signed multiply), DIVU, DIVS, NEG (additive negation), and CMP (a sort of comparison done by subtracting the arguments and setting the status bits, but did not store the result)

- Binary-coded decimal arithmetic: ABCD, and SBCD

- Logic: EOR (exclusive or), AND, NOT (logical not), OR (inclusive or)

- Shifting: (logical, i.e. right shifts put zero in the most-significant bit) LSL, LSR, (arithmetic shifts, i.e. sign-extend the most-significant bit) ASR, ASL, (rotates through eXtend and not) ROXL, ROXR, ROL, ROR

- Bit test and manipulation in memory: BSET (to 1), BCLR (to 0), BCHG (invert bit) and BTST (set the zero bit if tested bit is 0)

- Multiprocessing control: TAS, test-and-set, performed an indivisible bus operation, permitting semaphores to be used to synchronize several processors sharing a single memory

- Flow of control: JMP (jump), JSR (jump to subroutine), BSR (relative address jump to subroutine), RTS (return from subroutine), RTE (return from exception, i.e. an interrupt), TRAP (trigger a software exception similar to software interrupt), CHK (a conditional software exception)

- Branch: Bcc (where the "cc" specified one of 16 tests of the condition codes in the status register: equal, greater than, less-than, carry, and most combinations and logical inversions, available from the status register).

- Decrement-and-branch: DBcc (where "cc" was as for the branch instructions), which decremented a D-register and branched to a destination provided the condition was still true and the register had not been decremented to −1. This use of −1 instead of 0 as the terminating value allowed the easy coding of loops that had to do nothing if the count was 0 to begin with, without the need for an additional check before entering the loop. This also facilitated nesting of DBcc.

68EC000

The 68EC000 is a low-cost version of the 68000, designed for embedded controller applications. The 68EC000 can have either a 8-bit or 16-bit data bus, switchable at reset.[23]

The processors are available in a variety of speeds including 8 and 16 MHz configurations, producing 2,100 and 4,376 Dhrystones each. These processors have no floating-point unit, and it is difficult to implement an FPU coprocessor (MC68881/2) with one because the EC series lacks necessary coprocessor instructions.

The 68EC000 was used as a controller in many audio applications, including Ensoniq musical instruments and sound cards, where it was part of the MIDI synthesizer.[24] On Ensoniq sound boards, the controller provided several advantages compared to competitors without a CPU on board. The processor allowed the board to be configured to perform various audio tasks, such as MPU-401 MIDI synthesis or MT-32 emulation, without the use of a TSR program. This improved software compatibility, lowered CPU usage, and eliminated host system memory usage.

The Motorola 68EC000 core was later used in the m68k-based DragonBall processors from Motorola/Freescale.

It also was used as a sound controller in the Sega Saturn game console and as a controller for the HP JetDirect Ethernet controller boards for the mid-1990s LaserJet printers.

Example code

The 68000 assembler code below is for a subroutine named strtolower, which copies a source null-terminated ASCIZ character string to another destination string, converting all alphabetic characters to lower case.

00100000

00100000 CE56 0000

00100004 206E 0008

00100008 226E 000C

0010000C 1018

0010000E 0C00 0041

00100012 650A

00100014 0C00 005A

00100018 6204

0010001A 0600 0020

0010001E 12E0

00100020 66E8

00100022 4E5E

00100024 4E75

00100026

|

; strtolower:

; Copy a null-terminated ASCII string, converting

; all alphabetic characters to lower case.

;

; Entry parameters:

; (SP+0): Source string address

; (SP+4): Target string address

org $00100000 ;Start at 00100000

strtolower public

link a6,#0 ;Set up stack frame

movea 8(a6),a0 ;A0 = src, from stack

movea 12(a6),a1 ;A1 = dst, from stack

loop move.b (a0)+,d0 ;Load D0 from (src), incr src

cmpi #'A',d0 ;If D0 < 'A',

blo copy ;skip

cmpi #'Z',d0 ;If D0 > 'Z',

bhi copy ;skip

addi #'a'-'A',d0 ;D0 = lowercase(D0)

copy move.b d0,(a1)+ ;Store D0 to (dst), incr dst

bne loop ;Repeat while D0 <> NUL

unlk a6 ;Restore stack frame

rts ;Return

end

|

The subroutine establishes a call frame using register A6 as the frame pointer. This kind of calling convention supports reentrant and recursive code and is typically used by languages like C and C++. The subroutine then retrieves the parameters passed to it (src and dst) from the stack. It then loops, reading an ASCII character (a single byte) from the src string, checking whether it is an alphabetic character, and if so, converting it into a lower-case character, then writing the character into the dst string. Finally, it checks whether the character was a null character; if not, it repeats the loop, otherwise it restores the previous stack frame (and A6 register) and returns. Note that the string pointers (registers A0 and A1) are auto-incremented in each iteration of the loop.

In contrast, the code below is for a stand-alone function, even on the most restrictive version of AMS for the TI-89 series of calculators, being kernel-independent, with no values looked up in tables, files or libraries when executing, no system calls, no exception processing, minimal registers to be used, nor the need to save any. It is valid for historical Julian dates from 1 March 1 AD, or for Gregorian ones. In less than two dozen operations it calculates a day number compatible with ISO 8601 when called with three inputs stored at their corresponding LOCATIONS:

; ; WDN, an address - for storing result d0 ; FLAG, 0 or 2 - to choose between Julian or Gregorian, respectively ; DATE, year0mda - date stamp as binary word&byte&byte in basic ISO-format ;(YEAR, year ~ YEAR=DATE due to big-endianess) ; move.l DATE,d0 move.l d0,d1 ; ; Apply step 1 - Lachman's method of congruence andi.l #$f00,d0 divu #100,d0 addi.w #193,d0 andi.l #$ff,d0 divu #100,d0 ; d0 contains the month index in the upper word ; ; Apply step 2 - Using spqr as the Julian year of the last leap day swap d0 andi.l #$ffff,d0 add.b d1,d0 add.w YEAR,d0 subi.l #$300,d1 lsr #2,d1 swap d1 add.w d1,d0 ; spqr/4 + year + mi + da ; ; (Apply step 0 - Gregorian adjustment) mulu FLAG,d1 divu #50,d1 mulu #25,d1 lsr #2,d1 add.w d1,d0 add.w FLAG,d0 ; (sp32div16) + spqr/4 + year + mi + da ; divu #7,d0 swap d0 ; d0.w becomes the day number ; move.w d0,WDN ; returns the day number to address WDN rts ; ; Days of the week correspond to day numbers of the week as: ; Sun=0 Mon=1 Tue=2 Wed=3 Thu=4 Fri=5 Sat=6 ;

See also

- DTACK Grounded – an early 68000 newsletter

- Freescale 68HC11 – 8-bit embedded

- MacsBug – low-level assembly/machine-level debugger

- Motorola 68000 family

- Motorola 6800 – an 8-bit predecessor

- Motorola 6809 – another 8-bit CPU from Motorola

- x86 – the Intel competitor

- Transistor count

- Instructions per second

- Zilog Z8000 – 16-bit

Notable systems

- The original Apple Macintosh and early successors use the 68000 processor as their CPU.

- The original Apollo Computer workstations, DN100, DN400 and DN600 use two 68000 processors as main CPU.

- The 1981 SUN workstation and its subsequent commercial spinoff the 1982 Sun-1 workstation used the 68000 as their CPU.

- The Sega Genesis game console uses a 68000 processor (clocked at 7.67 MHz, 15/7 of the NTSC video colorburst frequency) as its main CPU and the Sega CD attachment for it uses another 68000 (clocked at 12.5 MHz).

- SNK's Neo Geo.

- The Commodore Amiga 1000, 2000, 500, 600 and CDTV use the 68000 processor as their CPU.[25]

- The Atari ST computers use the 68000 processor, initially with a clock speed of 8 MHz, and later switchable to 16 MHz in the Mega STe.

- CDTV, the world's first compact disc based multimedia platform, uses the 68000 processor as its CPU.[26]

- The TI-89 Graphing Calculator uses the 68000 processor at 10, 12, or 16 MHz, depending on the calculator's hardware version.

- The CP System uses the 68000 processor at 10 MHz; meanwhile the CP System II uses it at 16 MHz.

References

- ^ Motorola M68000 Family Programmer's Reference Manual (PDF). Phoenix, AZ: Motorola. 1992. p. 1-1. ISBN 0-13-723289-6.

- ^ a b Starnes, Thomas (April 1983). "Design Philosophy Behind Motorola's MC68000". easy68k.com. BYTE Publications Inc. Retrieved 2015-02-04.

- ^ Ken Polsson. "Chronology of Microprocessors". Processortimeline.info. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ^ a b c DTACK GROUNDED, The Journal of Simple 68000/16081 Systems, March 1984, p. 9.

- ^ Rood, Andrew L.; Cline, Robert C.; Brewster, Jon A. (September 1986). "UNIX and the MC68000". BYTE. p. 179.

- ^ "FD1094 – Sega Retro". segaretro.org.

- ^ "Company Briefs", The New York Times, September 21, 1985, available from TimesSelect (subscription).

- ^ "68HC001 obsoletes 68008", Microprocessor Report, June 20, 1990; available from HighBeam Research (subscription). Archived May 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Motorola streamlines 68000 family; "EC" versions of 68000, '020, '030, and '040, plus low-end 68300 chip", Microprocessor Report, April 17, 1991; available from HighBeam Research (subscription). Archived May 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Motorola reveals MC68SEC000 processor for low power embedded applications" at the Wayback Machine (archived March 28, 1997), Motorola press release, November 18, 1996.

- ^ comp.sys.m68k Usenet posting, May 16, 1995; also see other posts in thread. The end-of-life announcement was in late 1994; according to standard Motorola end-of-life practice, final orders would have been in 1995, with final shipments in 1996.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Multiprotocol processor marries 68000 and RISC", ESD: The Electronic System Design Magazine, November 1, 1989; available from AccessMyLibrary.

- ^ "museum ~ WICAT 150". Old-computers.com. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ^ [2] "Google Code, No Name Mame, namcos2.c", Retrieved 2016-1-15.

- ^ [3] "openlase-mame / xmame-0.106 / src / drivers / segaybd.c", Retrieved 2016-1-15.

- ^ [4] "Google Code, No Name Mame, cischeat.c", Retrieved 2016-1-15.

- ^ [5] "historic-mess / src / mame/ drivers / cischeat.c", Retrieved 2016-1-15.

- ^ Philips PM3320 250 MS/s Dual Channel Digital Storage Oscilloscope Service Manual, Section 8.6, ordering code 4822 872 05315.

- ^ LeCroy 9400/9400A Digital Oscilloscope Service Manual, Section 1.1.1.3 Microprocessor, August 1990.

- ^ a b M68000 8-/16-/32-Bit Microprocessors User's Manual Ninth Edition (PDF). Motorola. 1993. p. 6-2.

- ^ http://oldwww.nvg.ntnu.no/amiga/MC680x0_Sections/timstandard.HTML

- ^ Boys, Robert. M68k Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ), comp.sys.m68k, October 19, 1994.

- ^ Soundscape Elite Specs. from Fax Sheet, Google Groups, April 25, 1995.

- ^ "Commodore Amiga 1000 computer". Oldcomputers.net. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ^ Gareth Knight (2002-08-13). "Amiga CDTV". Amigahistory.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

Further reading

- M68000 Microprocessor Users Manual (9th Edition); Motorola (Freescale); 224 pages; 1996.

- Addendum to M68000 User Manual (Rev 0); Motorola (Freescale); 26 pages; 1997.

- M68000 Family Programmer's Reference Manual; Motorola (Freescale); 646 pages; 1991; ISBN 978-0137232895.

External links

- comp.sys.m68k FAQ

- Descriptions of assembler instructions

- 68000 images and descriptions at cpu-collection.de

- 'Chips : Of Diagnostics & Debugging' Article

- EASy68K, an open-source 68k assembler for Windows.

- Feralcore, an open-source 68k emulator, disassembler, and debugger for Java.

- Kiwi - a 68k Homebrew Computer

- m88k - Motorola's VME based 68k boards