Murder on the Orient Express

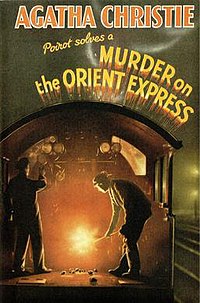

Dust-jacket illustration of the first UK edition | |

| Author | Agatha Christie |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Unknown |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Crime novel |

| Publisher | Collins Crime Club |

Publication date | 1 January 1934 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 256 pp (first edition, hardcover) |

| ISBN | NA Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

| Preceded by | The Hound of Death |

| Followed by | Unfinished Portrait |

Murder on the Orient Express is a detective novel by Agatha Christie featuring the Belgian detective Hercule Poirot. It was first published in the United Kingdom by the Collins Crime Club on 1 January 1934.[1] In the United States, it was published later in the same year under the title of Murder in the Calais Coach by Dodd, Mead and Company.[2][3] The U.K. edition retailed at seven shillings and sixpence (7/6)[4] and the U.S. edition at $2.00.[3]

The U.S. title of Murder in the Calais Coach was used to avoid confusion with the 1932 Graham Greene novel Stamboul Train which had been published in the United States as Orient Express.[5]

Plot summary

Upon arriving at the Tokatlian Hotel in Istanbul, private detective Hercule Poirot receives a telegram prompting him to cancel his arrangements and return to London, England. He instructs the concierge to book a first-class compartment on the Orient Express leaving that night. After boarding, Poirot is approached by Mr. Ratchett, a malevolent American he initially saw at the Tokatlian. Ratchett believes his life is being threatened and attempts to hire Poirot but, due to his distaste, Poirot refuses. "I do not like your face, Mr. Ratchett," he says.

On the second night of the journey, the train is stopped by a snowdrift near Vinkovci. Several events disturb Poirot's sleep, including a cry emanating from Ratchett's compartment. The next morning, Mr. Bouc, an acquaintance of Poirot and director of the company operating the Orient Express, informs him that Ratchett has been murdered and asks Poirot to investigate, in order to avoid complications and bureaucracy when the Yugoslav police arrive. Poirot accepts.

After examining the body and Ratchett's compartment, Poirot ascertains Ratchett's real identity and possible motives for his murder. A few years before, in the United States, three-year-old heiress Daisy Armstrong was kidnapped by a man named Cassetti. Cassetti eventually killed the child, despite collecting the ransom from the wealthy Armstrong family. The shock devastated the family, leading to a number of deaths and suicides. Cassetti was caught, but fled the country after he was acquitted. It is suspected that Cassetti used his considerable resources to rig the trial. Poirot concludes that Ratchett was, in fact, Cassetti.

As Poirot pursues his investigation, he discovers that everyone in the coach had a connection to the Armstrong family and, therefore, had a motive to kill Ratchett. Poirot proposes two possible solutions, leaving it to Bouc to decide which solution to put forward to the authorities. The first solution is that a stranger boarded the train and murdered Ratchett. The second solution is that all 13 people in the coach were complicit in the murder, seeking the justice that Ratchett had averted in the United States. He concedes Countess Andrenyi did not take part, so the murderers numbered 12, resembling a self-appointed jury. Mrs. Hubbard, revealed to be Linda Arden, Daisy Armstrong's grandmother, confesses that the second solution is correct.

Plot detail

The crime scene

Hercule Poirot, the internationally famous murder detective, boards the Orient Express (Simplon-Orient-Express) in Istanbul. The train is unusually crowded for the time of year. Poirot secures a berth only with the help of his friend Monsieur Bouc, a director of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits. When a Mr. Harris fails to show up, Poirot takes his place. On the second night, Poirot gets a compartment to himself.

During the journey, Poirot is approached by one of the passengers, Mr. Ratchett, an American businessman, who claims his life is in danger. He produces a small gun that he carries at all times, saying he believes it is necessary. He wants to hire Poirot to discover who is threatening him. Despite offers of increasingly substantial sums of money, Poirot declines Ratchett's offer, saying, "I do not like your face".

That night, in Vinkovci, at about 23 minutes before 1:00 a.m., Poirot wakes to the sound of a scream. It seems to come from the compartment next to his, which is occupied by Mr. Ratchett. When Poirot peeks out his door, he sees the conductor knock on Mr. Ratchett's door and ask if he is all right. A man's voice replies in French, "Ce n'est rien. Je me suis trompé," which means "It's nothing. I was mistaken," and the conductor moves on to answer another bell further down the passage. Poirot decides to go back to bed, but is disturbed by the fact that the train is unusually still.

As he lies awake, he hears Mrs. Hubbard ringing the bell urgently. When Poirot rings the conductor for a bottle of mineral water, he learns that Mrs. Hubbard claimed that someone had been in her compartment. He learns that the train has stopped as the result of a large snowdrift blocking the track. He dismisses the conductor and tries to go back to sleep, only to be awakened again by a knock on his door. This time, when Poirot gets up and looks out his door, the passage outside his compartment is empty, except for a woman in a scarlet kimono retreating down the passage in the distance. The next day, he awakens to find that Ratchett is dead, having been stabbed 12 times in his sleep. Bouc suggests that Poirot take the case, as he is so experienced with similar mysteries. Nothing more is required than for him to sit, think, and take in the available evidence.

The evidence

The door to Ratchett's compartment was locked and chained. One of the windows is open. Some of the stab wounds are very deep, at least three are lethal, and some are glancing blows. Furthermore, some of the wounds appear to have been inflicted by a right-handed person and some by a left-handed person. The pistol Ratchett carried is discovered under his pillow, unfired. A glass on the nightstand is examined and revealed to be drugged. A small pocket watch is discovered in Ratchett's pajamas, broken and stopped at 1:15 a.m.

Poirot finds several more clues in the victim's cabin and on board the train, including a woman's linen handkerchief embroidered with the initial "H", a pipe cleaner, and a button from a conductor's uniform. All of these clues suggest that the murderer or murderers were somewhat sloppy. However, each clue seemingly points to different suspects, which suggests that some of the clues were planted.

By reconstructing parts of a burned letter, Poirot discovers that Ratchett was a notorious fugitive from the United States named Cassetti. Five years earlier, Cassetti kidnapped three-year-old American heiress Daisy Armstrong. Although the Armstrong family paid a large ransom, Cassetti murdered the little girl long before the ransom deadline and fled the country with the money. Daisy's mother, Sonia, was pregnant when she heard of Daisy's death. The shock sent her into premature labour, and both she and the baby died. Her husband, Colonel Armstrong, shot himself out of grief. Daisy's nursemaid, Susanne, was suspected of complicity in the crime by the police, despite her protests. She threw herself out of a window and died, although she was later proved innocent. Although Cassetti was caught, his resources allowed him to get himself acquitted on an unspecified technicality, although he still fled the country to escape further prosecution for the crime. As the evidence mounts, it continues to point in different directions, giving the appearance that Poirot is being challenged by a mastermind. A critical piece of missing evidence—the scarlet kimono worn the night of the murder by an unknown woman—turns up on top of Poirot's own luggage.

The solution

After meditating on the evidence, Poirot assembles Bouc and Dr. Constantine, along with the 13 suspects, in the restaurant car, and lays out two possible explanations of Ratchett's murder. The first explanation is that a stranger—some gangster enemy of Ratchett—boarded the train at Vinkovci, the last stop, murdered Ratchett for reasons unknown, then escaped unnoticed and it is possible that the man has already left Yugoslavia. The crime occurred an hour earlier than everyone thought, because the victim and several others failed to note that the train had just crossed into a different time zone. The other noises heard by Poirot on the coach that evening were unrelated to the murder. However, Dr. Constantine objects, saying that Poirot must surely be aware that this does not explain the circumstances of the case.

Poirot's second explanation is much longer and rather more sensational: all of the suspects are guilty. Poirot's suspicions were first aroused by the fact that all the passengers on the train were of so many different nationalities and social classes, and that only in the "melting pot" of the United States would a group of such different people form some connection with each other.

Poirot reveals that the 13 other passengers on the train, and the train conductor, were all connected to the Armstrong family in some way:

- Hector Willard MacQueen, Ratchett/Cassetti's secretary was devoted to Sonia Armstrong. MacQueen's father was the district attorney for the kidnapping case. He knew from his father the details of Cassetti's escape from justice and intended to kill Ratchett.

- Edward Henry Masterman, Ratchett/Cassetti's valet, was Colonel Armstrong's batman during the war, and later his valet, who also acted as butler to the Armstrong household.

- Colonel Arbuthnot was Colonel Armstrong's comrade and best friend.

- Mrs. Hubbard is, in actuality, Linda Arden (maiden name Goldenberg), the most famous tragic actress of the New York stage, and was Sonia Armstrong's mother and Daisy's grandmother.

- Countess Andrenyi (née Helena Goldenberg) was Sonia Armstrong's sister.

- Count Andrenyi was the husband of Helena Andrenyi.

- Princess Natalia Dragomiroff was Sonia Armstrong's godmother, and a friend of her mother.

- Miss Mary Debenham was Sonia Armstrong's secretary and Daisy Armstrong's governess.

- Fräulein Hildegarde Schmidt, Princess Dragomiroff's maid, was the Armstrong family's cook.

- Antonio Foscarelli, a car salesman based in Chicago, was the Armstrong family's chauffeur.

- Miss Greta Ohlsson, a Swedish missionary, was Daisy Armstrong's nurse.

- Pierre Michel, the train conductor, was the father of Susanne, the Armstrong's nursemaid who committed suicide.

- Cyrus Hardman, a private detective ostensibly retained as a bodyguard by Ratchett/Cassetti, was a policeman in love with Susanne.

All these friends and relations had been gravely affected by Daisy's murder, and outraged by Cassetti's subsequent escape. They took it into their own hands to serve as Cassetti's executioners, to avenge a crime the law was unable to punish. Each of the suspects stabbed Ratchett once, so that no one could know who delivered the fatal blow. Twelve of the conspirators participated to allow for a "12-person jury", with Countess Andrenyi taking no part in the crime as she would have been suspected the most, so her husband took her place. One extra berth was booked under a fictitious name– Harris –so that no one but the conspirators and the victim would be on board the coach, and this fictitious person would subsequently disappear and become the primary suspect in Ratchett's murder. (The only people not involved in the plot would be "M. Bouc," for whom the cabin next to Ratchett had already been reserved, and Dr Constantine.) The main inconvenience for the executioners was the snowstorm and the last minute, unwelcome presence of Poirot, which caused complications resulting in several crucial clues being left behind.

Poirot summarises that there was no other way the murder could have taken place, given the evidence. Several of the suspects have broken down in tears as he has revealed their connection to the Armstrong family, and Mrs. Hubbard/Linda Arden confesses that the second theory is correct, but begs Poirot to tell the authorities that she acted alone as Cassetti's murderess. The evidence could be skewed to implicate her and she declares she would gladly go to prison if it meant the other passengers were spared. She points out that everyone present has suffered because of Cassetti's misdeeds, that there would likely have been other victims like Daisy if Cassetti had gone unpunished, and that Colonel Arbuthnot and Mary Debenham are in love. Fully in sympathy with the Armstrong family, and feeling nothing but disgust for the victim, Bouc pronounces the first explanation as correct. Poirot and Dr. Constantine agree. The doctor suggests he will edit his original report of the murder as he now "recognizes" some mistakes he has made, which clearly indicate that Poirot's first explanation was correct, after all. Poirot announces that he has "the honour to retire from the case".

Arrangement of the Calais Coach:

| Corridor | ||||||||||||||

| Pullman Coach | Michel | 16. Hardman | 15. Arbuthnot | 14. Dragomiroff | 13. R. Andrenyi | 12. H. Andrenyi | 3. Hubbard | 2. Ratchett | 1. Poirot | 10. Ohlsson 11. Debenham |

8. Schmidt 9. |

6. MacQueen 7. |

4. Masterman 5. Foscarelli |

Dining Car |

Reception

The Times Literary Supplement of 11 January 1934 outlined the plot and concluded that "The little grey cells solve once more the seemingly insoluble. Mrs. Christie makes an improbable tale very real, and keeps her readers enthralled and guessing to the end."[6]

In The New York Times Book Review of 4 March 1934, Isaac Anderson wrote, "The great Belgian detective's guesses are more than shrewd; they are positively miraculous. Although both the murder plot and the solution verge upon the impossible, Agatha Christie has contrived to make them appear quite convincing for the time being, and what more than that can a mystery addict desire?"[7]

The reviewer in The Guardian of 12 January 1934 stated that the murder would have been "perfect" had Poirot not been on the train and also overheard a conversation between Miss Debenham and Colonel Arbuthnot before he boarded; however, "The 'little grey cells' worked admirably, and the solution surprised their owner as much as it may well surprise the reader, for the secret is well kept and the manner of the telling is in Mrs. Christie's usual admirable manner."[8]

Robert Barnard: "The best of the railway stories. The Orient Express, snowed up in Yugoslavia, provides the ideal 'closed' set-up for a classic-style exercise in detection, as well as an excuse for an international cast-list. Contains my favourite line in all Christie: 'Poor creature, she's a Swede.' Impeccably clued, with a clever use of the Cyrillic script (cf. The Double Clue). The solution raised the ire of Raymond Chandler, but won't bother anyone who doesn't insist his detective fiction mirror real-life crime."[9] The reference is to Chandler's criticism of Christie in his essay The Simple Art of Murder.

References and allusions

References to actual history, geography and current science

The Armstrong kidnapping case was based on the actual kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh's son in 1932, just before the book was written. A maid employed by Mrs. Lindbergh's parents was suspected of involvement in the crime. After being harshly interrogated by police, she committed suicide. Another less-remembered real-life event also helped inspire the novel. Agatha Christie first travelled on the Orient Express in the autumn of 1928. Just a few months later, in February 1929, an Orient Express train was trapped by a blizzard near Cherkeskoy, Turkey, remaining marooned for six days.[10]

Christie herself was involved in a similar incident in December 1931 while returning from a visit to her husband's archaeological dig at Nineveh. The Orient Express train she was on was stuck for 24 hours due to rainfall, flooding, and sections of the track being washed away. Her authorised biography quotes in full a letter to her husband detailing the event. The letter includes descriptions of some passengers on the train, who influenced the plot and characters of the book, particularly an American lady, Mrs. Hilton, who was the inspiration for Mrs. Hubbard.[11]

Adaptations

Radio

John Moffatt starred as Poirot in a five-part BBC Radio 4 adaptation by Michael Blakewell, which was directed by Enyd Williams and originally broadcast from 28 December 1992 - 1 January 1993. André Maranne appeared as Bouc, Joss Ackland as Ratchett, Sylvia Syms as Mrs. Hubbard, Siân Phillips as Princess Dragomiroff, Francesca Annis as Mary Debenham, and Peter Polycarpou as Dr. Constantine.

Murder on the Orient Express (1974)

The book was made into a 1974 movie, which is considered one of the most successful cinematic adaptations of Christie's work ever. The film starred Albert Finney as Poirot, Martin Balsam as M. Bianchi (not Bouc), George Coulouris as Dr. Constantine, Richard Widmark as Ratchett, and an all-star cast of suspects including Sean Connery, Lauren Bacall, Anthony Perkins, John Gielgud, Michael York, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Jacqueline Bisset, Wendy Hiller, Vanessa Redgrave, Rachel Roberts, Colin Blakely, Denis Quilley, and Ingrid Bergman (who won the 1974 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role as Greta Ohlsson).

Only minor changes were made for the film: Masterman was renamed Beddoes, the dead maid was named Paulette instead of Susanne, Helena Goldenberg became Helena Grünwald (which is German for "Greenwood"), Antonio Foscarelli became Gino Foscarelli, Caroline Martha Hubbard became Harriet Belinda Hubbard, and the train line's Belgian/Flemish director, Monsieur Bouc, became instead an Italian director, Signor Bianchi.

Murder on the Orient Express (2001)

A thoroughly modernised and poorly received made-for-TV version starring Alfred Molina as Poirot was presented by CBS in 2001. This version, which costarred Meredith Baxter as Mrs. Hubbard, even implied that a woman was romantically interested in Poirot, had fewer suspects, and did away completely with the elegant clothing styles of the novel and the 1974 film.[12]

Poirot: Murder on the Orient Express (2010)

David Suchet reprises the role of Hercule Poirot in the television series co-produced by ITV Studios and WGBH-TV. The original air date was 11 July 2010 in the United States, and it was aired on Christmas Day 2010 in the UK.

The cast includes Dame Eileen Atkins, Hugh Bonneville, Jessica Chastain, Barbara Hershey, Toby Jones, and David Morrissey. Loosely faithful to the original story, it has a number of differences. Cyrus Hardman is omitted from the story, with Dr. Constantine taking his place among the "jury," as he was Mrs. Armstrong's American (instead of Greek) doctor who delivered Daisy Armstrong and the second (stillborn) child. Antonio Foscarelli becomes the lover of the maid, as well as being the chauffeur. The dead maid's name is changed from Susanne to Francoise. Most notably, instead of each member of the "jury" coming to Ratchett's compartment during the night and stabbing him one at a time in the dark, they line up and stab him one after the other in a well-lit room, resulting in him dying from the sheer quantity of wounds sustained, rather than the original novel leaving it unclear which one of the jury struck the fatal blow.

Greta Ohlsson (who in the novel was said to be a middle-aged lady) is changed to be a young girl in her early 20s, like Mary and Helena. There is also a discreetly implied romance between Greta and Antonio, as the two are seen together on several occasions towards the end of the film. Finally, the film takes place in September 1938, just before the outbreak of World War II, instead of 1936 as in most of the other episodes of the TV series. The atmosphere of this movie is unusually grim and gloomy, compared to other episodes in this series.

Following a trend of religious elements introduced into the series after 2003, the script includes extended religious and moral dialogues, including Ratchett showing himself to be religious, telling Poirot that he wants to make amends for something unknown and feeling remorse for the evil he has done. Other deviations from the novel include scenes of the stoning of an adulteress on the streets of Istanbul witnessed by Poirot, Arbuthnot and Mary Debenham. Mary is paralysed in her right arm and shoulder due to a brutal injury given to her by Ratchett during Daisy's kidnapping. It is revealed that Ratchett's connections threatened to kill MacQueen if his father did not rig the trial. The adaptation is unusual in that the narrative begins with Poirot in the midst of solving his recent case in Palestine, referring to a case mentioned in the book. It is revealed that a woman was found dead with a broken neck, but it was not murder; a married soldier was dating her, gave false information to the detectives, and ended up committing suicide to avoid bringing disgrace upon his wife and his regiment. Helena's maiden name, along with that of their mother's name, is changed from Goldenberg to Wasserstein (German for "water stone"), then anglicised to Waterston. In the 1974 movie directed by Sidney Lumet, it had been Grünwald (German for "Greenwood"). Mrs. Hubbard/Linda Arden wears a black wig to hide her grey hair, as there was a danger of her being recognised.

The adaptation's ending also has a character very different from that of the original story, with an emphasis on Poirot's moral dilemma. Instead of being drugged unconscious, the drug paralyzes Casetti but leaves him fully conscious of his own execution, while Princess Natalia Dragomiroff tells him exactly who they are and why they are delivering his punishment.

Also, Poirot stubbornly refuses to acknowledge that justice has been done, and gives a fervent speech on the importance of the rule of law, warning that barbarism will prevail if individuals abandon it (apparently alluding to the crimes of the impending Second World War). Greta, whom Poirot admires for her good works and deep faith, firmly tells Poirot that Ratchett's escape from justice is what is wrong with Catholicism, which she says forgives crimes that God will never forgive, and claims she took part in the killing on God's orders. This is followed by an argument between Poirot and Bouc, who is sympathetic to the conspirators' motives. Poirot's refusal to show mercy causes Colonel Arbuthnot to draw a pistol with the intent of killing Poirot and Bouc and blaming it on Ratchett's "assassin", but he is stopped by the others, who force him to see that murdering Poirot and Bouc would make them (the conspirators) no better than Ratchett. This, Poirot's attitude towards the Istanbul stoning, and a conversation with Mary Debenham, culminate in Poirot presenting the police with the false account of the lone assassin. However, he does so far more grudgingly and unwillingly than in the original novel and previous film and television adaptations. The conspirators are relieved, but Poirot continues to struggle with his decision, barely able to hold back his tears as he walks away from the train.

The interior of the Orient Express was reproduced at Pinewood Studios in London, while other locations include the Freemason Hall, Nene Valley Railway, and a street in Malta (shot to represent Istanbul).[13]

Publication history

- 1934, Collins Crime Club (London), 1 January 1934, Hardcover, 256 pp.

- 1934, Dodd Mead and Company (New York), 1934, Hardcover, 302 pp.

- c.1934, Lawrence E. Spivak, Abridged edition, 126 pp.

- 1940, Pocket Books (New York), Paperback, (Pocket number 79), 246 pp.

- 1948, Penguin Books, Paperback, (Penguin number 689), 222 pp.

- 1959, Fontana Books (Imprint of HarperCollins), Paperback, 192 pp.

- 1965, Ulverscroft Large-print Edition, Hardcover, 253 pp. ISBN 0-7089-0188-3

- 1968, Greenway edition of collected works (William Collins), Hardcover, 254 pp.

- 1968, Greenway edition of collected works (Dodd Mead), Hardcover, 254 pp.

- 1978, Pocket Books (New York), Paperback

- 2006, Poirot Facsimile Edition (Facsimile of 1934 UK first edition), 4 September 2006, Hardcover, 256 pp. ISBN 0-00-723440-6

The story's first true publication was the US serialisation in six installments in the Saturday Evening Post from 30 September to 4 November 1933 (Volume 206, Numbers 14 to 19). The title was Murder in the Calais Coach, and it was illustrated by William C. Hoople.[14]

The UK serialisation appeared after book publication, appearing in three installments in the Grand Magazine, in March, April, and May 1934 (Issues 349 to 351). This version was abridged from the book version (losing some 25% of the text), was without chapter divisions, and named the Russian princess as Dragiloff instead of Dragomiroff. Advertisements in the back pages of the UK first editions of The Listerdale Mystery, Why Didn't They Ask Evans, and Parker Pyne Investigates claimed that Murder on the Orient Express had proven to be Christie's best-selling book to date and the best-selling book published in the Collins Crime Club series.

Book dedication

The dedication of the book reads:

"To M.E.L.M. Arpachiyah, 1933"

"M.E.L.M." is Christie's second husband, archaeologist Max Edgar Lucien Mallowan (1904–78). She dedicated four books to him, either singly or jointly, the others being The Sittaford Mystery (1931), Come Tell Me How You Live (1946), and Christie's final written work, Postern of Fate (1973).

Christie and Mallowan were married, after a short engagement, on 11 September 1930, followed by a honeymoon in Italy. After his final seasons working on someone else's dig (Reginald Campbell Thompson – see the dedication to Lord Edgware Dies), Max raised the funds to lead an expedition of his own. With sponsorship from the Trustees of the British Museum and the British School of Archeology in Iraq,[15] he set off in 1933 for a mound at Arpachiyah, north-west of Nineveh, where "after several anxious weeks... considerable quantities of beautifully decorated pottery and figures came to the surface."[16] A notable feature of this season is that, for the first time, Christie, the rank amateur, assisted the professionals in their work. She was responsible for keeping written records and proved highly adept at cleaning and re-assembling pottery fragments. As at Nineveh, she found the time to continue writing, with Orient Express, Why Didn't They Ask Evans, and Unfinished Portrait all being drafted at the dig[16] (although a claim has been made that Murder on the Orient Express was written in the Hotel Pera Palace in Istanbul – see External Links below). Despite this success, after 1933, Mallowan discontinued work in Iraq due to the worsening political situation, and moved on to Syria.

Dustjacket blurb

The blurb on the inside flap of the dust jacket of the first edition (which is also repeated opposite the title page) reads:

The famous Orient Express, thundering along on its three-day journey across Europe, came to a sudden stop in the night. Snowdrifts blocked the line at a desolate spot somewhere in the Balkans. Everything was deathly quiet. "Decidedly I suffer from the nerves," murmured Hercule Poirot, and fell asleep again. He awoke to find himself very much wanted. For in the night murder had been committed. Mr. Ratchett, an American millionaire, was found lying dead in his berth – stabbed. The untrodden snow around the train proved that the murderer was still on board. Poirot investigates. He lies back and thinks – with his little grey cells...

Murder on the Orient Express must rank as one of the most ingenious stories ever devised. The solution is brilliant. One can but admire the amazing resource of Agatha Christie.

References in other works

- The episode "Next Stop Murder" of the ABC television series Moonlighting spoofs the novel.

- The episode "It's Never Too Late for Now" of the NBC television series 30 Rock is a parody of Murder on the Orient Express.

- In palaeontology, the theory that multiple factors led to the Permian-Triassic extinction event, the largest mass extinction in Earth's history, is called the Murder on the Orient Express Model (a term first used by Douglas Erwin in 1993).

- In Muppets Tonight, episode 108, guest star Jason Alexander played Hercule Poirot in a sketch spoofing the novel called "Murder on the Disoriented Express," featuring Kermit the Frog as the conductor and Mr. Poodlepants as the victim. Other Muppets, including Dr. Bunsen Honeydew and Bobo the Bear, also appear, and confuse Poirot with Hercules and then Superman.

- Murder on the Orient Express was parodied on an episode of SCTV, in which the story has been turned into a B movie by William Castle, titled Death Takes No Holiday. John Candy plays Poirot, while Andrea Martin plays Agatha Christie. In the penultimate moment, when Poirot grills the suspect-passengers (floating the theory that perhaps the train itself is the murderer), the film cuts to William Castle, played by Dave Thomas, who tells the audience that he will let them select who is the murderer.

- In a 2008 episode of the British science fiction television series Doctor Who titled "The Unicorn and the Wasp," the eponymous Doctor meets Christie in 1926 while she is staying at a country house, where a murder takes place. The Doctor's partner, Donna Noble (who also references other books written by Christie, giving her continual inspiration throughout the episode), suggests that everyone present is responsible for the murder, referencing Christie's own Murder on the Orient Express, albeit before she would have actually written it, as it was not published until 1934. Later in 2014, the eighth series episode "Mummy on the Orient Express" would have the Doctor take his companion Clara on an adventure on the Orient Express, albeit one in space.

- Randall Garrett's fictional detective Lord Darcy is forced to solve a murder aboard a train in "The Napoli Express" (first published in "Lord Darcy Investigates" in 1983) in an alternate-history poke at the original Christie tale.

- In the episode "Murder on the Halloween Express" of Sabrina the Teenage Witch, Sabrina takes her mortal friends on a Halloween mystery train in the hopes of instilling some Halloween spirit in them, not knowing that the train is, in fact, an Other Realm Express. Sabrina's friends then transform into different characters in a murder case and Sabrina herself is left with investigating and solving the mystery ... or else they will never be able to leave the train.

- An episode of Futurama is called "Murder on the Planet Express," though the episode itself has no similarities.

International titles

Except where otherwise noted, all English translations mean "Murder on the Orient Express".

- Arabic: جريمة في قطار الشرق السريع

- Bengali: Raater Gaari

- Breton: Muntr en Orient-Express

- Bulgarian: Убийство в Ориент Eкспрес (=Ubiystvo v Orient Express, Murder on the Orient Express)

- Chinese: 东方快车谋杀案

- Croatian: Ubojstvo u Orijent Ekspresu

- Czech: Vražda v Orient-expresu (Murder on the Orient Express)

- Danish: Mordet i Orientekspressen

- Dutch: Moord in de Oriënt-expres

- Estonian: Mõrv Idaekspressis (Murder on the Orient Express) or Kes tappis ameeriklase? (Who Killed the American?)

- Finnish: Idän pikajunan arvoitus (The Riddle of the Orient Express)

- French: Le Crime de l'Orient-Express (The Crime of the Orient Express)

- German: Mord im Orient-Express (Murder on the Orient Express) (since 1974 (movie)), changed 1951: Der rote Kimono (The Red Kimono), first edition in 1934: Die Frau im Kimono (The Woman in a Kimono)

- Greek: Έγκλημα στο Εξπρές Οριάν (Crime on the Orient Express)

- Hebrew: "רצח באוריינט אקספרס"

- Hungarian: A behavazott express (The Express Stuck in Snow), Gyilkosság az Orient expresszen (Murder on the Orient Express)

- Icelandic: Morðið í austurlandahraðlestinni

- Indonesian: "Pembunuhan di Orient Express"

- Italian: Assassinio sull'Orient Express

- Japanese: オリエント急行の殺人 (=Oriento kyūkō no satsujin, Murder on the Orient Express)

- Korean: 오리엔트 특급 살인 (=Olienteu teuggeub sal-in, Murder on the Orient Express)

- Macedonian: Убиство во Ориент Експрес

- Malti: Qtil fuq l-Orient Express

- Norwegian: Mord på Orientekspressen

- Persian: قتل در قطار سریعالسیر شرق

- Polish: Morderstwo w Orient Expresie

- Portuguese (Brazilian): Assassinato no Expresso do Oriente (Murder on the Orient Express)

- Portuguese (European): Um Crime no Expresso Oriente (A Crime on the Orient Express)

- Romanian: Crimă în Orient Express (Murder on the Orient Express)

- Russian: Убийство в «Восточном экспрессе» (=Ubiystvo v «Vostochnom ekspresse», Murder on the Orient Express)

- Spanish: Asesinato en el Orient Express

- Slovak: Vražda v Orient exprese

- Slovenian: Umor v Orient Ekspresu

- Serbian: Ubistvo u Orijent ekspresu

- Swedish: Mordet på Orientexpressen

- Turkish: Doğu Ekspresinde Cinayet

References

- ^ The Observer, 31 December 1933 (p.

- ^ John Cooper and B.A. Pyke. Detective Fiction – the collector's guide: Second Edition (pp. 82, 86) Scholar Press. 1994. ISBN 0-85967-991-8

- ^ a b Steve Marcum. "American Tribute to Agatha Christie". Home.insightbb.com. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Chris Peers, Ralph Spurrier and Jamie Sturgeon. Collins Crime Club – A checklist of First Editions. Dragonby Press (Second Edition) March 1999 (p. 14)

- ^ Vanessa Wagstaff and Stephen Poole, Agatha Christie: A Readers Companion (p. 88). Aurum Press Ltd, 2004. ISBN 1-84513-015-4

- ^ The Times Literary Supplement, 11 January 1934 (p. 29)

- ^ The New York Times Book Review, 4 March 1934 (p. 11)

- ^ The Guardian, 12 January 1934 (p. 5)

- ^ Barnard, Robert. A Talent to Deceive – an appreciation of Agatha Christie – Revised edition (pp. 199–200). Fontana Books, 1990. ISBN 0-00-637474-3

- ^ Dennis Sanders and Len Lovallo. The Agatha Christie Companion (pp. 105–08) Delacorte Press, 1984.

- ^ Morgan, Janet. Agatha Christie, A Biography. (pp. 201–04) Collins, 1984; ISBN 0-00-216330-6

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0279250/combined

- ^ "Murder on the Orient Express | Agatha Christie - The official information and community site". Agatha Christie. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "Murder in the Calais Coach". EBSCOhost. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ Morgan. (pp. 205–206)

- ^ a b Morgan. (p. 206)

External links

- Murder on the Orient Express at the official Agatha Christie website

- Murder on the Orient Express (1974) at IMDb

- Murder on the Orient Express (2010) at IMDb

- British Museum webpage on the Mallowans' work at Arpachiyah

- Venice-Simplon Orient Express The train using original carriages from the Orient Express that Christie based her novel on

- Hotel Pera Palace where Christie supposedly wrote the novel, although this is not stated in either her official biography or her own Autobiography