Nord-Trøndelag

Nord-Trøndelag County

Nord-Trøndelag fylke | |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

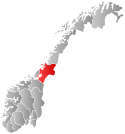

Nord-Trøndelag within Norway | |

| Coordinates: 64°30′00″N 11°40′00″E / 64.50000°N 11.66667°E | |

| Country | Norway |

| County | Nord-Trøndelag |

| District | Trøndelag |

| Established | 1804 |

| • Preceded by | Trondhjems amt |

| Disestablished | 1 Jan 2018 |

| • Succeeded by | Trøndelag county |

| Administrative centre | Steinkjer |

| Government | |

| • Body | Nord-Trøndelag County Municipality |

| Area (upon dissolution) | |

| • Total | 22,412 km2 (8,653 sq mi) |

| • Land | 20,777 km2 (8,022 sq mi) |

| • Water | 1,635 km2 (631 sq mi) 7.3% |

| • Rank | #6 in Norway |

| Population (2014) | |

| • Total | 135,142 |

| • Rank | #16 in Norway |

| • Density | 6/km2 (20/sq mi) |

| • Change (10 years) | |

| Demonym | Nord-Trønder[1] |

| Official language | |

| • Norwegian form | Neutral |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | NO-17[3] |

| Income (per capita) | 122,100 kr (2001) |

| GDP (per capita) | 194,803 kr (2001) |

| GDP national rank | #17 in Norway (1.63% of country) |

Nord-Trøndelag (Urban East Norwegian: [ˈnûːˌʈrœndəlɑːɡ] ; "North Trøndelag") was a county constituting the northern part of the present-day Trøndelag county in Norway. It bordered the old Sør-Trøndelag ("South Trøndelag") county as well as the county of Nordland. To the west is the Norwegian Sea (Atlantic Ocean), and to the east is Jämtland in Sweden. The county was established in 1804 when the old Trondhjems amt was divided into two: Nordre Trondhjems amt and Søndre Trondhjems amt. In 2016, the two county councils voted to merge (back) into a single county on 1 January 2018.[4]

As of 1 January 2014, the county had 135,142 inhabitants,[5] making it the country's fourth-least populated county. The largest municipalities are Stjørdal, Steinkjer (the county seat), Levanger, Namsos, and Verdal, all with between 24,000 and 12,000 inhabitants. The economy is primarily centered on services, although there are significant industries in agriculture, fisheries, hydroelectricity and forestry. It has the lowest gross domestic product per capita of any county in the country.

Nord-Trøndelag covered 22,412 square kilometres (8,653 sq mi), making it the sixth-largest county, and it consisted of 23 municipalities. The district of Innherred runs along the east side of the Trondheimsfjord, and is the most populated area, with much farming. To the south lies the district of Stjørdalen, while in the north, the larger district of Namdalen stretches from the Norwegian Sea to the mountains bordering Sweden. West of the Trondheimsfjord lays Fosen. Nord-Trøndelag bordered Sør-Trøndelag county to the south and Nordland county to the north. The western part of the county has several large valleys and consists largely of unpopulated wilderness, including four national parks. Snåsavatnet is the largest lake, while major rivers include Namsen, Verdalselva and Stjørdalselva.

Innherred was an important area during the Viking Age and featured the Battle of Stiklestad. The county was created in 1804 and was known as "Nordre Trondhjems amt" until 1919. Since the 1950s, the county has experienced a population growth below national levels. The axis north–south through the country past Grong and along the west side of Trondheim Fjord is a main transport artery, including the European Route E6 and the Nordland Line.

Geography

[edit]Nord-Trøndelag bordered Nordland to the north, Sør-Trøndelag to the south, Sweden to the east and the Norwegian Sea to the west. The county seat was the town of Steinkjer, with 20,527 inhabitants (2005). The largest lake is Snåsavatnet and the largest river is Namsen, one of the best salmon rivers in Europe. Other well known salmon rivers are as Verdalselva and Stjørdalselva. Salsvatnet is the second-deepest lake in Europe, with a maximum depth of 482 metres (1,581 ft). Another lake in the area is Byavatnet. Stjørdal is the biggest town in the county. There are local hospitals in Levanger and Namsos.

A large part of the population lives near the large Trondheimsfjord, which is a central feature of the southern part of this county. In the north are other fjords, mainly the Namsenfjord and Foldafjord. Areas on the eastern and northeastern shore of Trondheimsfjord (mainly in Stjørdal, Frosta, Levanger, Inderøy, Verdal, and Steinkjer) are fertile agricultural lowland, with grain fields and vegetables. Together with the grain fields in the Namdalen lowland, this forms the most northern grain cultivation area in Norway today.

However, the spruce dominated forest (some birch) covers a much larger area, and Nord-Trøndelag is the second largest timber producing county in Norway (after Hedmark). The forest and highland in Nord-Trøndelag is one of few places in Norway with four species of deer (moose, roe deer, red deer and reindeer). There are mountains near the border with Sweden, and coastal mountains with bare rock at the northern coast. The spruce forests occurs even at the coast, where some areas are classified as temperate rainforest (boreal rainforest, see Scandinavian coastal conifer forests). There are several national parks in the county, among them Blåfjella–Skjækerfjella National Park (one of the largest in Norway), Børgefjell National Park (partly), Lierne National Park and Skarvan and Roltdalen National Park (partly).

History

[edit]

The first people in Nord-Trøndelag settled in Flatanger and Leka between 7500 and 6000 BCE, and were migrating northwards along the coast. In about the same time, people moved upwards along the Trondheimsfjord.[6] The first farmers migrated to Stjørdal around 2000 BCE in the Stone Age.[7] Early agriculture was based mostly on animals, which allowed people to remain nomads and combine stockbreeding with gathering.[8] Around 2300 to 2000 BCE, the spruce spread into the county, and by 1300 CE, the landscape was dominated by spruce like today.[9] During the early Bronze Age, from 1800 to 1000 BCE, the first large graves were built in the Trondheimsfjord area.[7] The earliest species of cereals grown was barley around 500 BCE, which was later supplemented with other cereals.[8]

In the first century CE, iron mining in swamps started in the easternmost parts of the country. Several small communities with blast furnaces were established, located several days walk from the good agricultural land, generating trade and occupational specialization.[9] However, the mining industry stopped in the fifth century. In the following centuries, as part of the increased immigration due to the Migration Period, then a Germanic judicial system was introduced, which was a further development of the system launched during the mining era. In the fifth century, the first organizing of military took place, with constructions of small forts.[10] Around this time, the area was split into counties, with the current Nord-Trøndleag consisting of parts of Stjørdølafylke, Skøynafylke, Øynafylke, Verdølafylke, Sparbyggjafylke and Naumdølafylke.[11] From the tenth century, the Frostating was established as a thing for all of the Trondheimsfjord area.[12]

The largest hof for worshiping Nordic mythology was at Mære and was a common site for animal sacrifice.[13] In 997, Olaf Tryggvason established Nidaros (current-day Trondheim), in Sør-Trøndelag, started a series of attacks to conquer Innherred. To counteract, the Innherred warlords established a marketplace in Steinkjer. In the Battle of Stiklestad, which took place in 1030, King Olaf Haraldsson was killed by a peasant army in a battle for supremacy over Trøndelag.[11] In the following decades, despite the defeat of the Christian Olaf, Trøndelag was gradually Christianized, resulting in the construction of churches[14] and two monasteries.[15] By the 13th century, the Frostating laws had been codified, by which time all of Central Norway was under the thing, which developed into a court, which was moved to Nidaros in the 16th century.[16]

During the Viking Age, the population increased, reaching 20,000 by the mid-13th century. The Black Death killed off many people, and Nordli and Meråker were depopulated.[17] Sami people immigrated from the north in the following two centuries.[18] Archbishop of Nidaros, Olav Engelbrektsson, started building a fortress in Steinvikholmen in Stjørdal, which was completed in 1532, and became the center of the archdiocese. It remained until the Protestant Reformation in 1537, in which the king took over all church assets in the country, which consisted of nearly 40% of the land. Subsequently, the number of self-owning farmers increased.[19] The 16th century also saw the beginning of export of fish and lumber, and the first sawmills were established.[20] In the 17th century, administration gradually shifted from that of warlords to vogt, a representative of the king in Copenhagen. Taxes were increased to finance the military, and in Nord-Trøndelag, farmers had to join the military to fight Sweden in Jämtland.[21]

In the 18th century, confirmation and schools were introduced, and the potato was introduced during the 1770s. Parts of Namdalen was the target of immigrants from Eastern Norway, who cleared new land. In 1804, Trondhjems amt was split into two, with the northern part becoming Nordre Trondhjems amt. In 1919, it changed its name to Nord-Trøndelag. In 1838, the municipalities were created, and Nordre Trondhjems amt received 18.[22] In 1836, Levanger received status as a market-town, followed by Namsos in 1845 and Steinkjer in 1857.[23] The number would gradually increase to 48.[24]

In 1851, Marcus Thrane's public meetings caused riots demanding increased labor rights.[22] The first steam-powered sawmill was established at Spillum in 1853, and forestry started becoming a profession, rather than a part-time work during the winter. From the late 18th century, sail ships started running in regular traffic along the coast and in the fjord to Trondheim. Most natural resources were owned by the burgoise in Trondheim, as royal concession was needed for any exploitation.[20] During the last half of the 19th century, tens of thousands of people emigrated to North America, with some communities losing just under half their population.[23]

Industrialization started in the 1838 with steamships in regular traffic along the coast, and later on Trondheimsfjord and Snåsavatnet. At the end of the 19th century, the Great Transformation took place, whereby the economy changed from being predominantly based on self-production to a professional trades. Crofts were abolished. The Meråker Line reached Hell in 1881, and in 1905 the Hell–Sunnan Line reached Sunnan.[25] The first flight took off from Værnes in 1914, and in 1948 scheduled services were started to Oslo.[26]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 109,948 | — |

| 1961 | 116,760 | +6.2% |

| 1971 | 117,998 | +1.1% |

| 1981 | 125,835 | +6.6% |

| 1991 | 127,226 | +1.1% |

| 2001 | 127,261 | +0.0% |

| 2011 | 132,140 | +3.8% |

| Source: Statistics Norway.[27] | ||

As of 2010, Nord-Trøndelag had 131,555 inhabitants.[30] There were 55,910 households, or 2.3 people per household.[31] Life expectancy is 77.7 years for males and 82.4 years for females, both above the national average.[32] There were 5,942 foreigners, or 4.5%, including Norwegian-born to immigrant parents.[33] There were 4,699 people with foreign citizenship, the lowest for any county both in relative and absolute numbers.[34] The largest sources of immigration are Eastern Europe and Asia.[33]

Christianity is the dominant religion. As of 2010, 5,061 (3.8%) people were not registered as members of the Church of Norway. Of these, 2,581 (1.9%) were members of other Christian groups, while 1,762 (1.3%) were irreligious, 508 (0.3%) were Muslims, 158 were Buddhists, and 52 belonged to other religions.[35]

Trøndersk is a dialect of Norwegian which with minor modifications is spoken throughout Trøndelag and Nordmøre.[36][citation not found] It is characterized by the use of apocope,[36][citation not found] palatalization[37][citation not found] and retroflex flaps (thick "L").[36][citation not found] The Trøndersk spoken in Nord-Trøndelag is broader and closer to Old Norse than what is spoken in Trondheim, with the broadest language being spoken in Innherred. The towns in Nord-Trøndelag have been more influenced by written Norwegian and Standard Østnorsk and have a less broad dialect. Compared to Sør-Trøndelag, there is a tendency of utjamning rather than tiljamning. The use of dative case is gradually disappearing. About 300 Sami people,[38] which are concentrated around Snåsa, speak the Southern Sami language. It is not mutually intelligible with other Sami languages, and belongs to Uralic, a different language family than Norwegian.[39]

Government

[edit]Nord-Trøndelag County Municipality runs 3,000 kilometers (1,900 mi) of county roads,[40] public transport,[41] eleven upper secondary schools with 7,000 pupils,[42] regional development and other minor issues.[43] The county municipality is led by a 35-member county council, which in the 2007 election has consisted of members of seven parties.[44] The administration is led by a county cabinet with six members, representing the Labour Party, the Conservative Party, the Liberal Party and the Christian Democratic Party. The cabinet is led by Alf Daniel Moen of the Labour Party,[45] while Gunnar Viken of the Conservative Party is county mayor.[46]

The Nord-Trøndelag County Governor is the state's representative in the county. Since 2009, the governor has been Inge Ryan, a former parliamentarian for the Socialist Left Party.[47] The county is covered by three district courts, Inderøy District Court, located in Steinkjer,[48] Stjør- and Verdal District Court in Levanger,[49] and Namdal District Court in Namsos.[50] All are subordinate Frostating Court of Appeal.[51] The county is covered by Nord-Trøndelag Police District.[52]

Nord-Trøndelag also constitutes an electoral district for the Parliament of Norway, consisting of six representatives. In the 2009 election, the Labour Party received three representatives, Gerd Janne Kristoffersen, Arild Stokkan-Grande and Susanne Bratli, in addition to Robert Eriksson of the Progress Party, Lars Peder Brekk of the Centre Party, and Lars Myraune of the Conservative Party.[53] Since 2008, Brekk has been Minister of Agriculture and Food.[54]

Economy

[edit]

In 2007, Nord-Trøndelag had a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita NOK 242,895 and an income per capita of NOK 165,075, less than any other Norwegian county. For GDP per capita, Nord-Trøndelag lay at 67% of the national average, excluding the continental shelf, and lay just above a third of Oslo.[55]

Agriculture is most common east of the Trondheimsfjord, the lower parts of Indre Namdal and Nærøy.[56] 876 square kilometers (338 sq mi) of land is used for agriculture, of which 310 square kilometers (120 sq mi) is cereals,[57] which is more dominant along the Trondheimsfjord.[58] The county has ten percent of the country's agricultural output, and no other county has so high a percentage of its production from farming.[59] Farms traditionally have a square lot of buildings, with the house, called a trønderlån, being thin and long.[58] Fishing is an important industry along the coast, particularly in Ytre Namdal,[60] and Trondheim Fjord is the fjord with the highest yield in Norway.[61] Fish farming, particularly of salmon, has seen a rapid growth since the 1970s. Most of the fish is exported to Continental Europe, and to a less degree the Far East.[62]

Forty percent of the county is covered by forest, but about half of it is not profitable to log.[63] Parts of the forests are preserved, including the Coastal Spruce Forest, which is the only place in Europe where spruce grows out to the coast.[64] Up to 800,000 cubic meters (28,000,000 cu ft) of lumber is harvested each year, of which 95% is spruce and 3% is pine.[65] Statskog, a government agency, owns 7,330 square kilometres (2,830 sq mi) of Nord-Trøndelag, of which1,068 square kilometers (412 sq mi) is productive forest.[66] Large private forest owners include Værdalsbruket and Meraker Brug, while municipalities own 178 square kilometers (69 sq mi).[67] Norske Skog Skogn, established in 1962 and located at Skogn, is one of the largest companies in the county, and among Europe's largest producers of newsprint.[68] Södra Cell Folla in Follafoss is a producer of pulp.[69]

Hydroelectricity production in Nord-Trøndelag is for 2.9 TWh per year, all of which is owned by Nord-Trøndelag Elektrisitetsverk (NTE). Owned by the county municipality and established in 1919,[70] it also operates two wind farms, Vikna and Hundhammerfjellet.[71] Aker Verdal manufacturers jackets for oil platforms; established in 1976, it is among the largest employers in the county.[72]

Culture

[edit]

The county had four folk high schools: Sund, Namdal, Skogn and Bakketun.[73] The state-owned Nord-Trøndelag University College has campuses in Levanger, Steinkjer, Stjørdal and Namsos, and provides undergraduate education to 4,460 pupils.[74] The Central Norway Regional Health Authority is based in Stjørdal,[75] and its subsidiary Nord-Trøndelag Hospital Trust operates two hospitals, Levanger and Namsos.[76]

The traditional cuisine consisted of five meals per day, and contained herring, porridge, dairy products and flat bread, with the potato coming into use during the 19th century. Herring and potato became the standard meal for commoners.[77] Local specialties include ginger ale, akvavit, sodd, while it was common to use grævfisk and rakfisk (raw rotten fish) in the mountainous areas.[78]

Nord-Trøndelag Teater, located in Verdalsøra, is the only all-year professional theater.[79] Since 1954, The Saint Olav Drama has been performed at Stiklestad, portraying the battle.[80] Similarly, an outdoor midnight opera is held on Steinvikholmen portraying the historical events there.[81] Amateur revue is popular, and the Norwegian Revue Festival is held in Høylandet every other year.[82] Three bands Åge Aleksandersen, Hans Rotmo and DDE are the most successful music artists, having created the genre trønderrock. The former two had their breakthrough in the 1970s, while the latter had it in the 1990s.[83] Levanger HK plays in Premier Women's Handball League.[84] Saemien Sijte, located in Snåsa, is a center for Sami culture.

Trønder-Avisa, published in Steinkjer, is the only county-wide newspaper, although the Trondheim-based Adresseavisen also covers the county. Namdalsavisa, published in Namsos, covers Namdalen. Local newspapers, most of which cover a single municipality, are Frostingen, Inderøyningen, Innherreds Folkeblad og Verdalingen, Levanger-Avisa, Lokalavisa Verran Namdalseid, Meråkerposten, Snåsningen, Steinkjer-Avisa, Stjørdalens Blad and Ytringen.[85] The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation has offices in Steinkjer and runs radio programs exclusively for the county.

Transport

[edit]

European Route E6 runs north–south throughout eastern part the county, partially as a motorway. This route runs from Stjørdal via Steinkjer and Grong to Nordland. Other important routes in the county include E14 between Stjørdal via Meråker to Sweden, and County Road 17 from Steinkjer via Namsos and Nærøy to Nordland.[40] Both passenger and car ferries operate on the coast, and in Trondheimsfjord is the Levanger–Hokstad Ferry.[86] Private road transport is dominant, as public transport is sparsely operated. The largest bus company is TrønderBilene.[87]

The Nordland Line is a railway that runs from Trondheim to Bodø, and it runs north–south through the county.[25] South of Steinkjer, the Trøndelag Commuter Rail operates to Trondheim.[87] There are also two other lines; the Meråker Line, part of the line between Trondheim and Stockholm runs from Stjørdal to Meråker and onwards to Sweden.[25] The Namsos Line is purely used for freight and goes from Grong to Namsos.[88] All the railways are unelectrified. Trondheim Airport, Værnes, Norway's third-largest airport is located in Stjørdal, and serves most major airports in Norway, as well as European destinations. There are two regional airports, Namsos Airport, Høknesøra and Rørvik Airport, Ryum.[86] The Coastal Express ferry service calls at Rørvik.[89]

Municipalities

[edit]

Nord-Trøndelag has 23 municipalities as shown in the map.

| Municipality | Population | Area (km2) |

Area (sqmi) |

Center | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flatanger | 1,104 | 434.8 | 167.9 | Lauvsnes | [90] |

| Fosnes | 670 | 474.6 | 183.2 | Jøa | [91] |

| Frosta | 2,495 | 74.3 | 28.7 | Frosta | [92] |

| Grong | 2,361 | 1,114.3 | 430.2 | Medjå | [93] |

| Høylandet | 1,270 | 705.2 | 272.3 | Høylandet | [94] |

| Inderøy | 5,897 | 145.1 | 56.0 | Sakshaug | [95] |

| Leka | 593 | 108.0 | 41.7 | Leknes | [96] |

| Leksvik | 3,528 | 400.2 | 154.5 | Leksvik | [97] |

| Levanger | 18,580 | 611.3 | 236.0 | Levanger | [98] |

| Lierne | 1,435 | 2,640.0 | 1,019.3 | Sandvika | [99] |

| Meråker | 2,471 | 1,273.4 | 491.7 | Midtbygda | [100] |

| Nærøy | 4,990 | 1,013.5 | 391.3 | Kolvereid | [101] |

| Namdalseid | 1,697 | 737.9 | 284.9 | Namdalseid | [102] |

| Namsos | 12,795 | 757.1 | 292.3 | Namsos | [103] |

| Namsskogan | 928 | 1,368.1 | 528.2 | Namsskogan | [104] |

| Overhalla | 3,577 | 699.0 | 269.9 | Ranemsletta | [105] |

| Røyrvik | 495 | 1,334.6 | 515.3 | Røyrvik | [106] |

| Snåsa | 2,164 | 2,160.4 | 834.1 | Snåsa | [107] |

| Steinkjer | 21,080 | 1,427.5 | 551.2 | Steinkjer | [108] |

| Stjørdal | 21,375 | 919.8 | 355.1 | Stjørdalshalsen | [109] |

| Verdal | 14,222 | 1,488.5 | 574.7 | Verdalsøra | [110] |

| Verran | 2,914 | 558.5 | 215.6 | Malm | [111] |

| Vikna | 4,122 | 310.2 | 119.8 | Rørvik | [112] |

References

[edit]- ^ "Navn på steder og personer: Innbyggjarnamn" (in Norwegian). Språkrådet.

- ^ "Forskrift om målvedtak i kommunar og fylkeskommunar" (in Norwegian). Lovdata.no.

- ^ Bolstad, Erik; Thorsnæs, Geir, eds. (26 January 2023). "Kommunenummer". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Kunnskapsforlaget.

- ^ Hofstad, Sigrun (27 April 2016). "Her bankes det for et samlet Trøndelag" (in Norwegian). NRK.

- ^ "Færre flyttar til Noreg". ssb.no. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 39

- ^ a b Aune 1995, p. 43

- ^ a b Aune 1995, p. 45

- ^ a b Aune 1995, p. 46

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 48

- ^ a b Aune 1995, p. 64

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 62

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 54

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 57

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 60

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 63

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 65

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 196

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 68

- ^ a b Aune 1995, p. 70

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 72

- ^ a b Aune 1995, p. 76

- ^ a b Aune 1995, p. 74

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 248

- ^ a b c Aune 1995, p. 77

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 79

- ^ "Statistikkbanken". ssb.no. 26 May 2012. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Statistics Norway – Church of Norway. Archived 16 July 2012 at archive.today

- ^ "Statistics Norway – Members of religious and life stance communities outside the Church of Norway, by religion/life stance. County. 2006–2010". ssb.no. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Population, by age and county. Absolute figures. 1 January 2010". Statistics Norway. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Private households and persons per private household, by county. 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2001 and 2010". Statistics Norway. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Life expectancy – remaining years for males and females at selected ages, by county". Statistics Norway. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Life expectancy – remaining years for males and females at selected ages, by county". Statistics Norway. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Foreign citizens. Number and as a percentage of population, by county. 1 January 1976–2010". Statistics Norway. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Members of religious and life stance communities outside the Church of Norway, by religion/life stance". Statistics Norway.

- ^ a b c Halvorsen, Jemterud & Semmen 2000, p. 398

- ^ Halvorsen, Jemterud & Semmen 2000, p. 404

- ^ "Saami, South". Ethnologue. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 203

- ^ a b "Veg" (in Norwegian). Nord-Trøndelag County Municipality. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Kollektivtrafikk" (in Norwegian). Nord-Trøndelag County Municipality. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Utdanning" (in Norwegian). Nord-Trøndelag County Municipality. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Regional utvikling" (in Norwegian). Nord-Trøndelag County Municipality. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Medlemmer" (in Norwegian). Nord-Trøndelag County Municipality. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Fylkesrådet" (in Norwegian). Nord-Trøndelag County Municipality. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Fylkesordfører" (in Norwegian). Nord-Trøndelag County Municipality. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Om fylkesmannen" (in Norwegian). Nord-Trøndelag County Governor. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Inderøy tingrett" (in Norwegian). Norwegian National Courts Administration. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Stjør- og Verdal tingrett" (in Norwegian). Norwegian National Courts Administration. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Namdal tingrett" (in Norwegian). Norwegian National Courts Administration. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Frostating lagmannsrett" (in Norwegian). Norwegian National Courts Administration. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Nord-Trøndelag politidistrikt" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Police Service. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Dagens møtende" (in Norwegian). Parliament of Norway. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Brekk, Lars Peder" (in Norwegian). Parliament of Norway. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "BNP per sysselsatt høyest i Oslo" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 137

- ^ "Jordbruksareal, etter fylke og bruken av arealet" (in Norwegian). Statistics Norway. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ a b Aune 1995, p. 139

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 131

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 101

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 102

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 108

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 147

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 148

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 149

- ^ Aune 1995, pp. 152–153

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 154

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 155

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 238

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 235

- ^ "Vindkraft" (in Norwegian). Nord-Trøndelag Elektrisitetsverk. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 239

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 234

- ^ "English". Nord-Trøndelag University College. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Ledelse" (in Norwegian). Central Norway Regional Health Authority. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Helse Nord-Trøndelag" (in Norwegian). Central Norway Regional Health Authority. Archived from the original on 14 January 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 119

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 121

- ^ "Om teatret". Nord-Trøndelag Teater. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 161

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 162

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 163

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 176

- ^ "Postenligaen Kvinner, sesongen 1011". Norwegian Handball Federation. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "MEideregisteret". Norwegian Media Authority. Retrieved 22 December 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Aune 1995, p. 186

- ^ a b Aune 1995, p. 189

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 78

- ^ Aune 1995, p. 187

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Flatanger kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Fosnes kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Frosta kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Grong kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Flatanger kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Inderøy kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Leka kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Leksvik kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Levanger kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Lierne kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Meråker kommune" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Nærøy kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Namdalseid kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Namsos kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Namsskogan kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Overhalla kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Røyrvik kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Snåsa kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Steinkjer kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Stjørdal kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Verdal kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Verran kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Statistics Norway. "Tall om Vikna kommune" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Bibliography

- Aune, Tormod (1995). Hilsen Nord-Trøndelag (in Norwegian). Namsos: Trønderbok. ISBN 82-993613-0-3.