Plurality voting

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

Plurality voting is an electoral system in which each voter is allowed to vote for only one candidate, and the candidate who polls the most among their counterparts (a plurality) is elected. In a system based on single-member districts, it may be called first-past-the-post (FPTP), single-choice voting, simple plurality or relative/simple majority. In a system based on multi-member districts, it may be referred to as winner-takes-all or bloc voting. The system is often used to elect members of a legislative assembly or executive officers. It is the most common form of the system, and is used in most elections in the United States, the lower house (Lok Sabha) in India, elections to the House of Commons and English local elections in the United Kingdom.

Plurality voting is distinguished from a majoritarian electoral system, in which, to win, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of votes, i.e., more votes than all other candidates combined. Both systems may use single-member or multi-member constituencies. In the latter case it may be referred to as an exhaustive counting system: one member is elected at a time and the process repeated until the number of vacancies is filled.

In some jurisdictions, including France and some of the United States including Louisiana and Georgia, a "two-ballot" or "runoff election" plurality system is used. This may require two rounds of voting. If on the first round no candidate receives over 50% of the votes, then a second round takes place, with just the two highest-voted candidates in the first round. This ensures that the winner gains a majority of votes in the second round. Alternatively, all candidates above a certain threshold in the first round may compete in the second round. If there are more than two candidates standing, then a plurality vote may decide the result.

In political science, the use of plurality voting with multiple, single-winner constituencies to elect a multi-member body is often referred to as single-member district plurality or SMDP.[1] This combination is also variously referred to as winner-takes-all to contrast it with proportional representation systems. This term is sometimes also used to refer to elections for multiple winners in a particular constituency using bloc voting.

Voting

Plurality voting is used for local and/or national elections in 43 of the 193 countries that are members of the United Nations. Plurality voting is particularly prevalent in the United Kingdom and former British colonies, including the United States, Canada and India.[2]

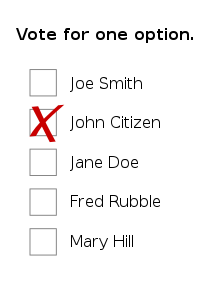

In single winner plurality voting, each voter is allowed to vote for only one candidate, and the winner of the election is whichever candidate represents a plurality of voters, that is, whoever received the largest number of votes. This makes plurality voting among the simplest of all electoral systems for voters and vote counting officials. (However the drawing of district boundary lines can be very contentious in this system.)

In an election for a legislative body, with single-member seats, each voter in a given geographically-defined electoral district is entitled to vote for one candidate from a list of candidates competing to represent that district. Under the plurality system, the winner of the election then becomes the representative of the entire electoral district, and serves with representatives of other electoral districts.

In an election for a single seat, such as for president in a presidential system, the same style of ballot is used and the winner is the candidate who receives the largest number of votes.

In the two-round system, usually the two highest polling candidates in the first ballot progress to the second round Run-off ballot.

In a multiple member plurality election, with n seats available, the winners are the n candidates with the highest numbers of votes. The rules may allow the voter to vote for one candidate, or for up to n candidates, or maybe some other number.

Ballot types

Generally plurality ballots can be categorized into two forms. The simplest form is a blank ballot where the name of a candidate(s) is written in by hand. A more structured ballot will list all the candidates and allow a mark to be made next to the name of a single candidate (or more than one, in some cases); however a structured ballot can also include space for a write-in candidate.

Examples of plurality voting

General elections in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom, like the United States and Canada, uses single-member districts as the base for national elections. Each electoral district (constituency) chooses one member of parliament, i.e. the candidate who gets the most votes, whether or not they get 50% or more of the votes cast ("first past the post"). In 1992, for example, a Liberal Democrat in Scotland won a seat with just 26% of the votes. This system of single-member districts with plurality winners tends to produce two large political parties; in countries with proportional representation there is not such a great incentive to vote for a large party, and that contributes to multi-party systems.

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland use the first past the post system for UK general elections, but use versions of proportional representation for elections to their own assemblies and parliaments. All of the UK has used a form of proportional representation for European Parliament elections.

The countries that inherited the British majoritarian system tend toward two large parties: one left, the other right, such as the U.S. Democrats and Republicans. Canada is an exception, with three major political parties consisting of the New Democratic Party which is to the left, the Conservative Party which is to the right and the Liberal Party which is slightly off center to the left. A fourth party that no longer has major party status is the separatist Bloc Québécois party, which is territorial and concentrated in Quebec. New Zealand used the British system, and it too yielded two large parties. It also left many New Zealanders unhappy, because other viewpoints were ignored, so its parliament in 1993 adopted a new electoral law, modelled on Germany's system of proportional representation (PR) with a partial selection by constituencies. New Zealand soon developed a more complex party system.[3]

After the 2015 Elections in the United Kingdom, there were calls from UKIP to change to proportional representation after receiving 3,881,129 votes but only 1 MP.[4] The Green Party was similarly under-represented. This contrasted greatly with the SNP in Scotland who only received 1,454,436 votes but won 56 seats, due to more concentrated support.

Example

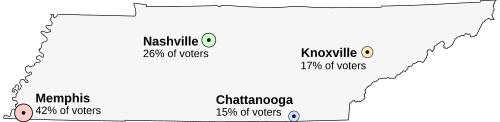

Suppose that Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is concentrated around four major cities. All voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, the largest city, but far from the others (42% of voters)

- Nashville, near the center of the state (26% of voters)

- Chattanooga, somewhat east (15% of voters)

- Knoxville, far to the northeast (17% of voters)

The preferences of each region's voters are:

| 42% of voters Far-West |

26% of voters Center |

15% of voters Center-East |

17% of voters Far-East |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

If each voter in each city naively selects one city on the ballot (Memphis voters select Memphis, Nashville voters select Nashville, and so on), then Memphis will be selected, as it has the most votes (42%). Note that this system does not require that the winner have a majority but only a plurality. Memphis wins because it has the most votes, even though 58% of the voters in this example preferred Memphis least. This problem does not arise with the two-round system, in which Nashville would have won. (In practice, with FPTP, many voters in Chattanooga and Knoxville are likely to vote tactically for Nashville: see below.)

Disadvantages

Tactical voting

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

To a much greater extent than many other electoral methods, plurality electoral systems encourage tactical voting techniques, like "compromising". Voters are under pressure to vote for one of the two candidates most likely to win even if their true preference is neither, because a vote for any other candidate is unlikely to lead to the preferred candidate being elected, but will instead reduce support for one of the two major candidates who the voter might prefer to the other—the minority party will simply take votes away from one of the major parties, potentially changing the outcome while gaining nothing. Any other party will typically need to build up its votes and credibility over a series of elections before it is seen as electable.

In the Tennessee example, if all the voters for Chattanooga and Knoxville had instead voted for Nashville, then Nashville would have won (with 58% of the vote); this would only have been the 3rd choice for those voters, but voting for their respective 1st choices (their own cities) actually results in their 4th choice (Memphis) being elected.

The difficulty is sometimes summed up, in an extreme form, as "All votes for anyone other than the second place are votes for the winner", because by voting for other candidates, they have denied those votes to the second place candidate who could have won had they received them. It is often claimed by United States Democrats that Democrat Al Gore lost the 2000 Presidential Election to Republican George W. Bush because some voters on the left voted for Ralph Nader of the Green Party, who exit polls indicated would have preferred Gore at 45% to Bush at 27%, with the rest not voting in Nader's absence.[5]

This thinking is illustrated by elections in Puerto Rico and its three principal voter groups: the Independentistas (pro-independence), the Populares (pro-commonwealth), and the Estadistas (pro-statehood). Historically, there has been a tendency for Independentista voters to elect Popular candidates and policies. This phenomenon is responsible for some Popular victories, even though the Estadistas have the most voters on the island. It is so widely recognised that the Puerto Ricans sometimes call the Independentistas who vote for the Populares "melons" (in reference to the party colors), because the fruit is green on the outside but red on the inside.

Because voters have to predict in advance who the top two candidates will be, this can cause significant perturbation to the system:

- Substantial power is given to the news media. Some voters will tend to believe the media's assertions as to who the leading contenders are likely to be in the election. Even voters who distrust the media will know that other voters do believe the media, and therefore those candidates who receive the most media attention will nonetheless be the most popular and thus most likely to be in one of the top two.

- A newly appointed candidate, who is in fact supported by the majority of voters, may be considered (due to the lack of a track record) not to be likely to become one of the top two candidates; thus, they will receive a reduced number of votes, which will then give them a reputation as a low poller in future elections, compounding the problem.

- The system may promote votes against more so than votes for. In the UK, entire campaigns have been organised with the aim of voting against the Conservative party by voting either Labour or Liberal Democrat. For example, in a constituency held by the Conservatives, with the Liberal Democrats as the second-place party and the Labour Party in third, Labour supporters might be urged to vote for the Liberal Democrat candidate (who has a smaller majority to close and more support in the constituency) than their own candidate on the basis that Labour supporters would prefer an MP from a competing left/liberal party than a Conservative one. Similarly, in Labour/Lib Dem marginals where the Conservatives are third, Conservative voters may be encouraged or tempted to vote Lib Dem to help defeat Labour.

- If enough voters use this tactic, the first-past-the-post system becomes, effectively, runoff voting—a completely different system—where the first round is held in the court of public opinion; a good example of this is the 1997 Winchester by-election.

Proponents of other single-winner electoral systems argue that their proposals would reduce the need for tactical voting and reduce the spoiler effect. Examples include the commonly used two-round system of runoffs and instant runoff voting, along with less tested systems such as approval voting, score voting and Condorcet methods.

Fewer political parties

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

Duverger's law is a theory that constituencies that use first-past-the-post systems will have a two-party system, given enough time.[6]

First-past-the-post tends to reduce the number of political parties to a greater extent than most other methods do, making it more likely that a single party will hold a majority of legislative seats. (In the United Kingdom, 21 out of 24 general elections since 1922 have produced a single-party majority government.)

FPTP's tendency toward fewer parties and more frequent one-party rules can also produce government that may not consider as wide a range of perspectives and concerns. It is entirely possible that a voter finds all major parties to have similar views on issues and that a voter does not have a meaningful way of expressing a dissenting opinion through their vote.

As fewer choices are offered to voters, voters may vote for a candidate although they disagree with them, because they disagree even more with their opponents. Consequently, candidates will less closely reflect the viewpoints of those who vote for them.

Furthermore, one-party rule is more likely to lead to radical changes in government policy even though the changes are favoured only by a plurality or a bare majority of the voters, whereas a multi-party system usually require greater consensus in order to make dramatic changes in policy.

Wasted votes

Wasted votes are those cast for candidates who are virtually sure to lose in a safe seat, and votes cast for winning candidates in excess of the number required for victory. For example, in the UK General Election of 2005, 52% of votes were cast for losing candidates and 18% were excess votes—a total of 70% wasted votes. This is perhaps the most fundamental criticism of FPTP, that a large majority of votes may play no part in determining the outcome. Alternative electoral systems attempt to ensure that almost all votes are effective in influencing the result, and vote wastage is consequently minimised.

Gerrymandering

Because FPTP permits a high level of wasted votes, an election under FPTP is easily gerrymandered unless safeguards are in place. In gerrymandering, a party in power deliberately manipulates constituency boundaries to unfairly increase the number of seats it wins.

In brief, suppose that governing party G wishes to reduce the seats that will be won by opposition party O in the next election. It creates a number of constituencies in each of which O has an overwhelming majority of votes. O will win these seats, but many of its voters will waste their votes. Then the rest of the constituencies are designed to have small majorities for G. Few G votes are wasted, and G will win many seats by small margins. As a result of the gerrymander, O's seats have cost it more votes than G's seats.

Manipulation charges

The presence of spoilers often gives rise to suspicions that manipulation of the slate has taken place. The spoiler may have received incentives to run. A spoiler may also drop out at the last moment, inducing charges that such an act was intended from the beginning.

Spoiler effect

The spoiler effect is the effect of vote splitting between candidates or ballot questions with similar ideologies. One spoiler candidate's presence in the election draws votes from a major candidate with similar politics thereby causing a strong opponent of both or several to win. Smaller parties can disproportionately change the outcome of an FPTP election by swinging what is called the 50-50% balance of two party systems, by creating a faction within one or both ends of the political spectrum which shifts the winner of the election from an absolute majority outcome to a simple majority outcome favouring the previously less favoured party. In comparison, for electoral systems using proportional representation small groups win only their proportional share of representation.

Issues specific to particular countries

Solomon Islands

In August 2008, Sir Peter Kenilorea commented on what he perceived as the flaws of a first-past-the-post electoral system in the Solomon Islands:

An[...] underlying cause of political instability and poor governance, in my opinion, is our electoral system and its related problems. It has been identified by a number of academics and practitioners that the First Past the Post system is such that a Member elected to Parliament is sometimes elected by a small percentage of voters where there are many candidates in a particular constituency. I believe that this system is part of the reason why voters ignore political parties and why candidates try an appeal to voters' material desires and relationships instead of political parties. [...] Moreover, this system creates a political environment where a Member is elected by a relatively small number of voters with the effect that this Member is then expected to ignore his party’s philosophy and instead look after that core base of voters in terms of their material needs. Another relevant factor that I see in relation to the electoral system is the proven fact that it is rather conducive, and thus has not prevented, corrupt elections practices such as ballot buying.

— "Realising political stability", Sir Peter Kenilorea, Solomon Star, 30 August 2008

International examples

The United Kingdom continues to use the first-past-the-post electoral system for general elections, and for local government elections in England and Wales. Changes to the UK system have been proposed, and alternatives were examined by the Jenkins Commission in the late 1990s. After the formation of a new coalition government in 2010, it was announced as part of the coalition agreement that a referendum would be held on switching to the alternative vote system. However the alternative vote system was rejected 2-1 by British voters in a referendum held on 5 May 2011.

Canada also uses FPTP for national and provincial elections. In May 2005 the Canadian province of British Columbia had a referendum on abolishing single-member district plurality in favour of multi-member districts with the Single Transferable Vote system after the Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform made a recommendation for the reform. The referendum obtained 57% of the vote, but failed to meet the 60% requirement for passing. An October 2007 referendum in the Canadian province of Ontario on adopting a Mixed Member Proportional system, also requiring 60% approval, failed with only 36.9% voting in favour.

Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales, the Republic of Ireland, Australia and New Zealand are notable examples of countries within the UK, or with previous links to it, that use non-FPTP electoral systems (Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales use FPTP in United Kingdom general elections, however).

Nations which have undergone democratic reforms since 1990 but have not adopted the FPTP system include South Africa, almost all of the former Eastern bloc nations, Russia, Afghanistan and Iraq.

List of countries

Countries that use plurality voting to elect the lower or only house of their legislature include:[7]

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Azerbaijan

- Bahamas

- Bangladesh

- Barbados

- Belize

- Bermuda

- Bhutan

- Botswana

- Burma (Myanmar)

- Canada

- Comoros

- Congo (Brazzaville)

- Cook Islands

- Cote d'Ivoire

- Dominica

- Eritrea

- Ethiopia

- Gabon

- Gambia

- Ghana

- Grenada

- India

- Iran

- Jamaica

- Kenya

- Kuwait

- Laos

- Liberia

- Malawi

- Malaysia

- Maldives

- Marshall Islands

- Micronesia

- Nigeria

- Niue

- Oman

- Palau

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Samoa

- Seychelles

- Sierra Leone

- Singapore

- Solomon Islands

- Swaziland

- Tanzania

- Tonga

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Tuvalu

- Uganda

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Yemen

- Zambia

See also

- 2006 Texas gubernatorial election - Example of an incumbent governor, Rick Perry, winning re-election despite gaining less than 40 percent of the vote

- Cube rule

- Deviation from proportionality

- Plurality-at-large voting

- List of democracy and elections-related topics

- Instant-runoff voting

- Approval Voting

- Score voting

- Single non-transferable vote

- Single transferable vote

- Runoff voting

References

- ^ "Plurality-Majority Systems". Mtholyoke.edu. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ "The Global Distribution of Electoral Systems". Aceproject.org. 20 May 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ Roskin, Michael, Countries and Concepts (2007)

- ^ "Reckless Out Amid UKIP Frustration At System". Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ Rosenbaum, David E. (24 February 2004). "THE 2004 CAMPAIGN: THE INDEPENDENT; Relax, Nader Advises Alarmed Democrats, but the 2000 Math Counsels Otherwise". New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ Bernard Grofman; André Blais; Shaun Bowler (5 March 2009). Duverger's Law of Plurality Voting: The Logic of Party Competition in Canada, India, the United Kingdom and the United States. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-09720-6.

- ^ "Electoral Systems". ACE Electoral Knowledge Network. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

The fatal flaws of Plurality (first-past-the-post) electoral systems - Proportional Representation Society of Australia