Portal:American Civil War/Grand Parade of the States

At the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861, Kansas was the newest U.S. state, admitted just months earlier in January. The state had formally rejected slavery by popular vote and vowed to fight on the side of the Union, though ideological divisions with neighboring Missouri, a slave state, had led to violent conflict in previous years and persisted for the duration of the war.

While Kansas was a rural frontier state, distant from the major theaters of war, and its Unionist government was never seriously threatened by Confederate military forces, several engagements did occur within its borders, as well as countless raids and skirmishes between local irregulars, including the Lawrence Massacre by pro-Confederate guerrillas under William Quantrill in August 1863. Later the state witnessed the defeat of Confederate General Sterling Price by Union General Alfred Pleasonton at the Battle of Mine Creek, the second-largest cavalry action of the war. Additionally, some of the Union's first Black regiments would form in the state of Kansas. These contributions would inform the complicated race relations in the state during the reconstruction era (1865–1877). (Full article...)

Alabama was central to the Civil War, with the secession convention at Montgomery, the birthplace of the Confederacy, inviting other slaveholding states to form a southern republic, during January–March 1861, and to develop new state constitutions. The 1861 Alabaman constitution granted citizenship to current U.S. residents, but prohibited import duties (tariffs) on foreign goods, limited a standing military, and as a final issue, opposed emancipation by any nation, but urged protection of African-American slaves with trials by jury, and reserved the power to regulate or prohibit the African slave trade. The secession convention invited all slaveholding states to secede, but only 7 Cotton States of the Lower South formed the Confederacy with Alabama, while the majority of slave states were in the Union at the time of the founding of the Confederacy. Congress had voted to protect the institution of slavery by passing the Corwin Amendment on March 4, 1861, but it was never ratified.

Even before secession, the governor of Alabama Andrew B. Moore defied the United States government by seizing the two federal forts at the Gulf Coast (forts Morgan and Gaines) and the arsenal at Mount Vernon in January 1861 to distribute weapons to Alabama towns. The peaceful seizure of Alabama forts preceded by three months the bombing and capture of the Union's Fort Sumter (SC) on April 12, 1861. (Full article...)

During the American Civil War, Arkansas was a Confederate state, though it had initially voted to remain in the Union. Following the capture of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Abraham Lincoln called for troops from every Union state to put down the rebellion, and Arkansas along with several other southern states seceded. For the rest of the civil war, Arkansas played a major role in controlling the Mississippi River, a major waterway.

Arkansas raised 48 infantry regiments, 20 artillery batteries, and over 20 cavalry regiments for the Confederacy, mostly serving in the Western Theater, though the Third Arkansas served with distinction in the Army of Northern Virginia. Major-General Patrick Cleburne was the state's most notable military leader. The state also supplied four infantry regiments, four cavalry regiments and one artillery battery of white troops for the Union and six infantry regiments and one artillery battery of "U.S. Colored Troops." (Full article...)

The Arizona Territory, colloquially referred to as Confederate Arizona, was an organized incorporated territory of the Confederate States of America that existed from August 1, 1861, to May 26, 1865, when the Confederate States Army Trans-Mississippi Department, commanded by General Edmund Kirby Smith, surrendered at Shreveport, Louisiana. However, after the Battle of Glorieta Pass, the Confederates had to retreat from the territory, and by July 1862, effective Confederate control of the territory had ended. Delegates to the secession convention had voted in March 1861 to secede from the New Mexico Territory and the Union, and seek to join the Confederacy. It consisted of the portion of the New Mexico Territory south of the 34th parallel, including parts of the modern states of New Mexico and Arizona. The capital was Mesilla, along the southern border. The breakaway region overlapped Arizona Territory, established by the Union government in February 1863.

Arizona was proclaimed a Confederate territory on August 1, 1861, after Colonel John R. Baylor's victory at the Battle of Mesilla. His hold on the area was broken after Glorieta Pass (March 26–28, 1862), the defining battle of the New Mexico Campaign. In July 1862, the Confederate territorial government withdrew to El Paso, Texas. With the approach of Union troops, it relocated to San Antonio, where it remained for the duration of the civil war. The territory continued to be represented in the Confederate States Congress, and Confederate troops continued to fight under the Arizona banner until the war ended. (Full article...)

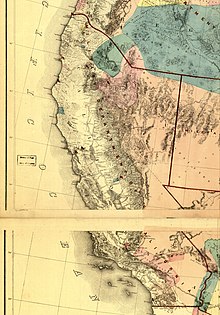

California's involvement in the American Civil War included sending gold east to support the war effort, recruiting volunteer combat units to replace regular U.S. Army units sent east, in the area west of the Rocky Mountains, maintaining and building numerous camps and fortifications, suppressing secessionist activity (many of these secessionists went east to fight for the Confederacy) and securing the New Mexico Territory against the Confederacy. The State of California did not send its units east, but many citizens traveled east and joined the Union Army there, some of whom became famous.

Democrats had dominated the state from its inception, and Southern Democrats were sympathetic to secession. Although they were a minority in the state, they had become a majority in Southern California and Tulare County, and large numbers resided in San Joaquin, Santa Clara, Monterey, and San Francisco counties. California was home for powerful businessmen who played a significant role in Californian politics through their control of mines, shipping, finance, and the Republican Party but Republicans had been a minority party until the secession crisis. The Civil War split in the Democratic Party allowed Abraham Lincoln to carry the state, albeit by only a slim margin. Unlike most free states, Lincoln won California with only a plurality as opposed to the outright majority in the popular vote. (Full article...)

The Colorado Territory was formally created in 1861 shortly before the bombardment of Fort Sumter sparked the American Civil War. Although sentiments were somewhat divided in the early days of the war, Colorado was only marginally a pro-Union territory (four statehood attempts were thwarted, largely by Confederate sympathizers in July 1862, February 1863, February 1864, and January 1866). Colorado was strategically important to both the Union and Confederacy because of the gold and silver mines there as both sides wanted to use the mineral wealth to help finance the war. The New Mexico Campaign (February to April 1862) was a military operation conducted by Confederate Brigadier General Henry Sibley to gain control of the Southwest, including the gold fields of Colorado, the mineral-rich territory of Nevada and the ports of California. The campaign was intended as a prelude to an invasion of the Colorado Territory and an attempt to cut the supply lines between California and the rest of the Union. However, the Confederates were defeated at the Battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico and were forced to retreat back to Texas, effectively ending the New Mexico Campaign. (Full article...)

The New England state of Connecticut played an important role in the American Civil War, providing arms, equipment, technology, funds, supplies, and soldiers for the Union Army and the Union Navy. Several Connecticut politicians played significant roles in the Federal government and helped shape its policies during the war and the Reconstruction. (Full article...)

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States, was the center of the Union war effort, which rapidly turned it from a small city into a major capital with full civic infrastructure and strong defenses.

The shock of the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, with demoralized troops wandering the streets of the capital, caused President Abraham Lincoln to order extensive fortifications and a large garrison. That required an influx of troops, military suppliers and building contractors, which would set up a new demand for accommodation, including military hospitals. The abolition of slavery in Washington in 1862 also attracted many freedmen to the city. Except for one attempted invasion by Confederate cavalry leader Jubal Early in 1864, the capital remained impregnable. (Full article...)

Slavery had been a divisive issue in Delaware for decades before the American Civil War began. Opposition to slavery in Delaware, imported from Quaker-dominated Pennsylvania, led many slaveowners to free their slaves; half of the state's black population was free by 1810, and more than 90% were free by 1860. This trend also led pro-slavery legislators to restrict free black organizations, and the constabulary in Wilmington was accused of harsh enforcement of runaway slave laws, while many Delawareans kidnapped free blacks among the large communities throughout the state and sold them to plantations further south. During the Civil War, Delaware was a slave state that remained in the Union. (Delaware voters voted not to secede on January 3, 1861.) Although most Delaware citizens who fought in the Civil War served in regiments on the Union side, some did, in fact, serve in Delaware companies on the Confederate side in the Maryland and Virginia Regiments. Delaware was the one slave state from which the Confederate States of America could not recruit a full regiment. (Full article...)

Florida participated in the American Civil War as a member of the Confederate States of America. It had been admitted to the United States as a slave state in 1845. In January 1861, Florida became the third Southern state to secede from the Union after the November 1860 presidential election victory of Abraham Lincoln. It was one of the initial seven slave states which formed the Confederacy on February 8, 1861, in advance of the American Civil War.

Florida had by far the smallest population of the Confederate states with about 140,000 residents, nearly half of them enslaved people. As such, Florida sent around 15,000 troops to the Confederate army, the vast majority of which were deployed elsewhere during the war. The state's chief importance was as a source of cattle and other food supplies for the Confederacy, and as an entry and exit location for blockade-runners who used its many bays and small inlets to evade the Union Navy. (Full article...)

Georgia was one of the original seven slave states that formed the Confederate States of America in February 1861, triggering the U.S. Civil War. The state governor, Democrat Joseph E. Brown, wanted locally raised troops to be used only for the defense of Georgia, in defiance of Confederate president Jefferson Davis, who wanted to deploy them on other battlefronts. When the Union blockade prevented Georgia from exporting its plentiful cotton in exchange for key imports, Brown ordered farmers to grow food instead, but the breakdown of transport systems led to desperate shortages.

There was not much fighting in Georgia until September 1863, when Confederates under Braxton Bragg defeated William S. Rosecrans at Chickamauga Creek. In May 1864, William T. Sherman started pursuing the Confederates towards Atlanta, which he captured in September, in advance of his March to the Sea. This six-week campaign destroyed much of the civilian infrastructure of Georgia, decisively shortening the war. When news of the march reached Robert E. Lee's army in Virginia, whole Georgian regiments deserted, feeling they were needed at home. The Battle of Columbus, fought on the Georgia-Alabama border on April 16, 1865, is reckoned by some criteria to have been the last battle of the war. (Full article...)

After the outbreak of the American Civil War, the Kingdom of Hawaii under King Kamehameha IV declared its neutrality on August 26, 1861. However, many Native Hawaiians and Hawaii-born Americans (mainly descendants of the American missionaries), abroad and in the islands, enlisted in the military regiments of various states in the Union and the Confederacy. (Full article...)

The history of Idaho in the American Civil War is atypical, as the territory was far from the battlefields. At the start of the Civil War, modern-day Idaho was part of the Washington Territory. On March 3, 1863, the Idaho Territory was formed, consisting of the entirety of modern-day Idaho, Montana, and all but southwest Wyoming. However, there were concerns about Confederate sympathizers in the eastern half of the territory, in what is present-day Montana. As a result, in 1863 Sidney Edgerton traveled quickly to see President Abraham Lincoln about the situation; this was one reason to split the Montana Territory from the Idaho Territory. The split also resulted in most of Idaho Territory's land consisting of modern-day Wyoming being reassigned to the Dakota Territory. (Full article...)

During the American Civil War, the state of Illinois was a major source of troops for the Union Army (particularly for those armies serving in the Western Theater of the Civil War), and of military supplies, food, and clothing. Situated near major rivers and railroads, Illinois became a major jumping off place early in the war for Ulysses S. Grant's efforts to seize control of the Mississippi and Tennessee rivers. Statewide, public support for the Union was high despite Copperhead sentiment.

The state was energetically led throughout the war by Governor Richard Yates. Illinois contributed 250,000 soldiers to the Union Army, ranking it fourth in terms of the total manpower in Federal military service. Illinois troops predominantly fought in the Western Theater, although a few regiments played important roles in the East, particularly in the Army of the Potomac. Several thousand Illinoisians were killed or died of their wounds during the war, and a number of national cemeteries were established in Illinois to bury their remains.

In addition to President Abraham Lincoln, a number of other Illinois men became prominent in the army or in national politics, including generals, Ulysses S. Grant, John M. Schofield and John A. Logan, Senator Lyman Trumbull, and Representative Elihu P. Washburne. No major battles were fought in the state, although several river towns became sites for important supply depots and "brownwater" navy yards. Several prisoner of war camps and prisons dotted the state after 1863, processing thousands of captive Confederate soldiers. (Full article...)

During the American Civil War, most of what is now the U.S. state of Oklahoma was designated as the Indian Territory. It served as an unorganized region that had been set aside specifically for Native American tribes and was occupied mostly by tribes which had been removed from their ancestral lands in the Southeastern United States following the Indian Removal Act of 1830. As part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the Indian Territory was the scene of numerous skirmishes and seven officially recognized battles involving both Native American units allied with the Confederate States of America and Native Americans loyal to the United States government, as well as other Union and Confederate troops.

Most tribal leaders in Indian Territory aligned with the Confederacy. A total of at least 7,860 Native Americans from the Indian Territory participated in the Confederate Army, as both officers and enlisted men; most came from the Five Civilized Tribes: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations. The Union organized several regiments of the Indian Home Guard to serve in the Indian Territory and occasionally in adjacent areas of Kansas, Missouri, and Arkansas. (Full article...)

Indiana, a state in the Midwest, played an important role in supporting the Union during the American Civil War. Despite anti-war activity within the state, and southern Indiana's ancestral ties to the South, Indiana was a strong supporter of the Union. Indiana contributed approximately 210,000 Union soldiers, sailors, and marines. Indiana's soldiers served in 308 military engagements during the war; the majority of them in the western theater, between the Mississippi River and the Appalachian Mountains. Indiana's war-related deaths reached 25,028 (7,243 from battle and 17,785 from disease). Its state government provided funds to purchase equipment, food, and supplies for troops in the field. Indiana, an agriculturally rich state containing the fifth-highest population in the Union, was critical to the North's success due to its geographical location, large population, and agricultural production. Indiana residents, also known as Hoosiers, supplied the Union with manpower for the war effort, a railroad network and access to the Ohio River and the Great Lakes, and agricultural products such as grain and livestock. The state experienced two minor raids by Confederate forces, and one major raid in 1863, which caused a brief panic in southern portions of the state and its capital city, Indianapolis.

Indiana experienced significant political strife during the war, especially after Governor Oliver P. Morton suppressed the Democratic-controlled state legislature, which had an anti-war (Copperhead) element. Major debates related to the issues of slavery and emancipation, military service for African Americans, and the draft, ensued. These led to violence. In 1863, after the state legislature failed to pass a budget and

left the state without the authority to collect taxes, Governor Morton acted outside his state's constitutional authority to secure funding through federal and private loans to operate the state government and avert a financial crisis. (Full article...)

The state of Iowa played a significant role during the American Civil War in providing food, supplies, troops and officers for the Union army. (Full article...)

Kentucky was a southern border state of key importance in the American Civil War. It officially declared its neutrality at the beginning of the war, but after a failed attempt by Confederate General Leonidas Polk to take the state of Kentucky for the Confederacy, the legislature petitioned the Union Army for assistance. Though the Confederacy controlled more than half of Kentucky early in the war, after early 1862 Kentucky came largely under U.S. control. In the historiography of the Civil War, Kentucky is treated primarily as a southern border state, with special attention to the social divisions during the secession crisis, invasions and raids, internal violence, sporadic guerrilla warfare, federal-state relations, the ending of slavery, and the return of Confederate veterans. Kentucky was the site of several fierce battles, including Mill Springs and Perryville. It was the arena to such military leaders as Ulysses S. Grant on the Union side, who first encountered serious Confederate gunfire coming from Columbus, Kentucky, and Confederate cavalry leader Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest proved to be a scourge to the Union Army in western Kentucky, even making an attack on Paducah. Kentuckian John Hunt Morgan further challenged Union control, as he conducted numerous cavalry raids through the state. (Full article...)

Louisiana was a dominant population center in the southwest of the Confederate States of America, controlling the wealthy trade center of New Orleans, and contributing the French Creole and Cajun populations to the demographic composition of a predominantly Anglo-American country. In the antebellum period, Louisiana was a slave state, where enslaved African Americans had comprised the majority of the population during the eighteenth-century French and Spanish dominations. By the time the United States acquired the territory (1803) and Louisiana became a state (1812), the institution of slavery was entrenched. By 1860, 47% of the state's population were enslaved, though the state also had one of the largest free black populations in the United States. Much of the white population, particularly in the cities, supported slavery, while pockets of support for the U.S. and its government existed in the more rural areas.

Louisiana declared that it had seceded from the Union on January 26, 1861. Civil-War era New Orleans, the largest city in the South, was strategically important as a port city due to its southernmost location on the Mississippi River and its access to the Gulf of Mexico. The U.S. War Department early on planned for its capture. The city was taken by U.S. Army forces on April 25, 1862. Because a large part of the population had Union sympathies (or compatible commercial interests), the U.S. government took the unusual step of designating the areas of Louisiana then under U.S. control as a state within the Union, with its own elected representatives to the U.S. Congress. For the latter part of the war, both the U.S. and the Confederacy recognized their own distinct Louisiana governors. Similarly, New Orleans and 13 named parishes of the state were exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation, which applied exclusively to states in rebellion against the Union. (Full article...)

As a fervently abolitionist and strongly Republican state, Maine contributed a higher proportion of its citizens to the Union armies than any other, as well as supplying money, equipment and stores. No land battles were fought in Maine. The only episode was the Battle of Portland Harbor (1863) that saw a Confederate raiding party thwarted in its attempt to capture a revenue cutter.

Abraham Lincoln chose Maine's Hannibal Hamlin as his first Vice President. The future General Joshua L. Chamberlain and the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment played a key role at the Battle of Gettysburg, and the 1st Maine Heavy Artillery Regiment lost more men in a single charge during the siege of Petersburg than any Union regiment in the war. (Full article...)

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Maryland, a slave state, was one of the border states, straddling the South and North. Despite some popular support for the cause of the Confederate States of America, Maryland did not secede during the Civil War. Governor Thomas H. Hicks, despite his early sympathies for the South, helped prevent the state from seceding.

Because the state bordered the District of Columbia and the opposing factions within the state strongly desired to sway public opinion towards their respective causes, Maryland played an important role in the war. The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (1861–1865) suspended the constitutional right of habeas corpus from Washington to Philadelphia. Lincoln ignored the ruling of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in "Ex parte Merryman" decision in 1861 concerning freeing John Merryman, a prominent Southern sympathizer arrested by the military. (Full article...)

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts played a significant role in national events prior to and during the American Civil War (1861–1865). Massachusetts Republicans dominated the early antislavery movement during the 1830s, motivating activists across the nation. This, in turn, increased sectionalism in the North and South, one of the factors that led to the war. Politicians from Massachusetts, echoing the views of social activists, further increased national tensions. The state was dominated by the Republican Party and was also home to many Republican leaders who promoted harsh treatment of slave owners and, later, the former civilian leaders of the Confederate States of America and the military officers in the Confederate Army. Once hostilities began, Massachusetts supported the war effort in several significant ways, sending 159,165 men to serve in the Union Army and the Union Navy for the loyal North. One of the best known Massachusetts units was the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, the first regiment of African American soldiers (led by white officers). Additionally, a number of important generals came from Massachusetts, including Benjamin F. Butler, Joseph Hooker, who commanded the Federal Army of the Potomac in early 1863, as well as Edwin V. Sumner and Darius N. Couch, who both successively commanded the II Corps of the Union Army. (Full article...)

Michigan made a substantial contribution to the Union during the American Civil War. While the state itself was far removed from the combat theaters of the war, Michigan supplied many troops and several generals, including George Armstrong Custer. When, at the beginning of the war, Michigan was asked to supply no more than one regiment, Governor Austin Blair sent seven. (Full article...)

Mississippi was the second southern state to declare its secession from the United States, doing so on January 9, 1861. It joined with six other southern states to form the Confederacy on February 4, 1861. Mississippi's location along the lengthy Mississippi River made it strategically important to both the Union and the Confederacy; dozens of battles were fought in the state as armies repeatedly clashed near key towns and transportation nodes.

Mississippian troops fought in every major theater of the American Civil War, although most were concentrated in the Western Theater. Confederate president Jefferson Davis was a Mississippi politician and operated a large cotton plantation there. Prominent Mississippian generals during the war included William Barksdale, Carnot Posey, Wirt Adams, Earl Van Dorn, Robert Lowry, and Benjamin G. Humphreys. (Full article...)

During the American Civil War, Missouri was a hotly contested border state populated by both Union and Confederate sympathizers. It sent armies, generals, and supplies to both sides, maintained dual governments, and endured a bloody neighbor-against-neighbor intrastate war within the larger national war. A slave state since statehood in 1821, Missouri's geographic position in the central region of the country and at the rural edge of the American frontier ensured that it remained a divisive battleground for competing Northern and Southern ideologies in the years preceding the war. When the war began in 1861, it became clear that control of the Mississippi River and the burgeoning economic hub of St. Louis would make Missouri a strategic territory in the Trans-Mississippi Theater. (Full article...)

The area that eventually became the U.S. state of Montana played little direct role in the American Civil War. The closest the Confederate States Army ever came to the area was New Mexico and eastern Kansas, each over a thousand miles away. There was not even an organized territory using "Montana" until the Montana Territory was created on May 26, 1864, three years after the Battle of Fort Sumter. In 1861, the area was divided between the Dakota Territory and the Washington Territory, and in 1863, it was part of the Idaho Territory.

Nevertheless, Confederate sympathizers did have a presence in what is now the U.S. state of Montana. Those in the Montana Territory who supported the Confederate side were varied. Among them were Confederate sympathizers who were determined that some of Montana's gold would go into the Southern instead of Northern coffers. But most were those who would rather not fight in the war, which ranged from pure drifters to actual Confederate deserters. (Full article...)

The present-day state of Nebraska was still a territory of the United States during the American Civil War. It did not achieve statehood until March 1867, two years after the war ended. Nevertheless, the Nebraska Territory contributed significantly to the Union war effort. (Full article...)

Nevada's entry into statehood in the United States on October 31, 1864, in the midst of the American Civil War, was expedited by Union sympathizers in order to ensure the state's participation in the 1864 presidential election in support of President Abraham Lincoln. Thus Nevada became one of only two states admitted to the Union during the war (the other being West Virginia) and earned the nickname that appears on the Nevada state flag today: "Battle Born". Because its population at statehood was less than 40,000, Nevada was only able to muster 1,200 men to fight for the Union Army, but Confederate forces never posed any serious threat of territorial seizure, and Nevada remained firmly in Union control for the duration of the war. Largely isolated from the major theaters of the conflict, Nevada nonetheless served as an important target for political and economic strategists before and after gaining statehood. Its main contribution to the cause came from its burgeoning mining industry: at least $400 million in silver ore from the Comstock Lode was used to finance the federal war effort. In addition, the state hosted a number of Union military posts. (Full article...)

New Hampshire was a member of the Union during the American Civil War. The state gave soldiers, money, and supplies to the Union Army. It sent 31,657 enlisted men and 836 officers, of whom about 20% were killed in action or died from disease or accident. (Full article...)

The state of New Jersey in the United States provided a source of troops, equipment and leaders for the Union during the American Civil War. Though no major battles were fought in New Jersey, soldiers and volunteers from New Jersey played an important part in the war, including Philip Kearny and George B. McClellan, who led the Army of the Potomac early in the Civil War and unsuccessfully ran for President of the United States in 1864 against his former commander-in-chief, Abraham Lincoln. (Full article...)

The New Mexico Territory, comprising what are today the U.S. states of New Mexico and Arizona, as well as the southern portion of Nevada, played a small but significant role in the trans-Mississippi theater of the American Civil War. Despite its remoteness from the major battlefields of the east, and its being part of the sparsely populated and largely undeveloped American frontier, both Confederate and Union governments claimed ownership over the territory, and several important battles and military operations took place in the region. Roughly 7,000-8,000 troops from the New Mexico Territory served the Union, more than any other western state or territory.

In 1861, the Confederacy claimed the southern half of the vast New Mexico Territory as its own Arizona Territory and waged the ambitious New Mexico Campaign in an attempt to control the American Southwest and open up access to Union-held California. Confederate power in the New Mexico Territory was effectively broken when the campaign culminated in the Union victory at the Battle of Glorieta Pass in 1862. Although the Confederacy never attempted another invasion of the region, its territorial government continued to operate out of Texas, with Confederate troops marching under the Arizona flag until the end of the war. (Full article...)

The state of New York during the American Civil War was a major influence in national politics, the Union war effort, and the media coverage of the war. New York was the most populous state in the Union during the Civil War, and provided more troops to the U.S. army than any other state, as well as several significant military commanders and leaders. New York sent 400,000 men to the armed forces during the war. 22,000 soldiers died from combat wounds; 30,000 died from disease or accidents; 36 were executed. The state government spent $38 million on the war effort; counties, cities and towns spent another $111 million, especially for recruiting bonuses.

The voters were sharply divided politically. A significant anti-war movement emerged, particularly in the mid- to late-war years. The Democrats were divided between War Democrats who supported the war and Copperheads who wanted an early peace. Republicans divided between moderates who supported Lincoln, and Radical Republicans who demanded harsh treatment of the rebel states. New York provided William H. Seward as Lincoln's Secretary of State, as well as several important voices in Congress. (Full article...)

During the American Civil War, North Carolina joined the Confederacy with some reluctance, mainly due to the presence of Southern Unionist sentiment within the state. A popular vote in February, 1861 on the issue of secession was won by the unionists but not by a wide margin.

This slight lean in favor of staying in the Union would shift towards the Confederacy in response to Abraham Lincoln's April 15 proclamation that requested 75,000 troops from all Union states, leading to North Carolina's secession. Similar to Arkansas, Tennessee, and Virginia, North Carolina wished to remain uninvolved in the likely war but felt forced to pick a side by the proclamation. Throughout the war, North Carolina widely remained a divided state. The population within the Appalachian Mountains in the western part of the state contained large pockets of Unionism. Even so, North Carolina would help contribute a significant amount of troops to the Confederacy, and channel many vital supplies through the major port of Wilmington, in defiance of the Union blockade. (Full article...)

During the American Civil War, the State of Ohio played a key role in providing troops, military officers, and supplies to the Union army. Due to its central location in the Northern United States and burgeoning population, Ohio was both politically and logistically important to the war effort. Despite the state's boasting a number of very powerful Republican politicians, it was divided politically. Portions of Southern Ohio followed the Peace Democrats and openly opposed President Abraham Lincoln's policies. Ohio played an important part in the Underground Railroad prior to the war, and remained a haven for escaped and runaway slaves during the war years. The third most populous state in the Union at the time, Ohio raised nearly 320,000 soldiers for the Union army, third behind only New York and Pennsylvania in total manpower contributed to the military and the highest per capita of any Union state. Several leading generals were from Ohio, including Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and Philip H. Sheridan. Five Ohio-born Civil War officers would later serve as the President of the United States. The Fighting McCooks gained fame as the largest immediate family group ever to become officers in the U.S. Army. (Full article...)

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Oregon had no organised militia and had sold most of the equipment bought for the Rogue River Wars. The state's governor, John Whiteaker, was pro-slavery and opposed to Oregon's involvement in the conflict. As such, it was only in late 1862 with a new governor that the state raised any troops: the 1st Oregon Cavalry served until June 1865.

During the Civil War, emigrants to the newfound gold fields in Idaho and Oregon continued to clash with the Paiute, Shoshone and Bannock tribes of Oregon, Idaho and Nevada until relations degenerated into the bloody 1864–1868 Snake War. The 1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment was formed in 1864 and its last company was mustered out of service in July 1867. Both units were used to guard travel routes and Indian reservations, escort emigrant wagon trains, and protect settlers from Indian raiders. Several infantry detachments also accompanied survey parties and built roads in central and southern Oregon. (Full article...)

During the American Civil War, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania played a critical role in the Union, providing a substantial supply of military personnel, equipment, and leadership to the Federal government. The state raised over 360,000 soldiers for the Federal armies. It served as a significant source of artillery guns, small arms, ammunition, armor for the new revolutionary style of ironclad types of gunboats for the rapidly expanding United States Navy, and food supplies. The Phoenixville Iron Company by itself produced well over 1,000 cannons, and the Frankford Arsenal was a major supply depot. Pennsylvania was the site of the bloodiest battle of the war, the Battle of Gettysburg, which became widely known as one of the turning points of the Civil War. Numerous more minor engagements and skirmishes were also fought in Pennsylvania during the 1863 Gettysburg Campaign, as well as the following year during a Confederate cavalry raid that culminated in the burning of much of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. (Full article...)

The state of Rhode Island during the American Civil War remained loyal to the Union, as did the other states of New England. Rhode Island furnished 25,236 fighting men to the Union Army, of which 1,685 died. The state used its industrial capacity to supply the Union Army with the materials needed to win the war. Rhode Island's continued growth and modernization led to the creation of an urban mass transit system and improved health and sanitation programs. (Full article...)

South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union in December 1860, and was one of the founding member states of the Confederacy in February 1861. The bombardment of the beleaguered U.S. garrison at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861, is generally recognized as the first military engagement of the war. The retaking of Charleston in February 1865, and raising the flag (the same flag) again at Fort Sumter, was used for the Union symbol of victory.

South Carolina provided around 60,000 troops for the Confederate Army. As the war progressed, former slaves and free blacks of South Carolina joined U.S. Colored Troops regiments for the Union Army (most Blacks in South Carolina were enslaved at the war's outset). The state also provided uniforms, textiles, food, and war material, as well as trained soldiers and leaders from The Citadel and other military schools. In contrast to most other Confederate states, South Carolina had a well-developed rail network linking all of its major cities without a break of gauge. (Full article...)

The American Civil War significantly affected Tennessee, with every county witnessing combat. During the War, Tennessee was a Confederate state, and the last state to officially secede from the Union to join the Confederacy. Tennessee had been threatening to secede since before the Confederacy was even formed, but didn’t officially do so until after the fall of Fort Sumter when public opinion throughout the state drastically shifted. Tennessee seceded in protest to President Lincoln's April 15 Proclamation calling forth 75,000 members of state militias to suppress the rebellion. Tennessee provided the second largest number of troops for the Confederacy, and would also provide more southern unionist soldiers for the Union Army than any other state within the Confederacy.

In February 1862, some of the war's first serious fighting took place along the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, recognized as major military highways, and mountain passes such as Cumberland Gap were keenly competed-for by both sides. The Battle of Shiloh and the fighting along the Mississippi brought glory to the then little-known Ulysses S. Grant, while his area commander Henry Halleck was rewarded with a promotion to General-in-Chief. The Tullahoma campaign, led by William Rosecrans, drove the Confederates from Middle Tennessee so quickly that they did not take many casualties, and were strong enough to defeat Rosecrans soon afterward. At Nashville in December 1864, George Thomas routed the Army of Tennessee under John Bell Hood, the last major battle fought in the state. (Full article...)

Texas declared its secession from the Union on February 1, 1861, and joined the Confederate States on March 2, 1861, after it had replaced its governor, Sam Houston, who had refused to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy. As with those of other states, the Declaration of Secession was not recognized by the US government at Washington, DC. Some Texan military units fought in the Civil War east of the Mississippi River, but Texas was more useful for supplying soldiers and horses for the Confederate Army. Texas' supply role lasted until mid-1863, when Union gunboats started to control the Mississippi River, which prevented large transfers of men, horses, or cattle. Some cotton was sold in Mexico, but most of the crop became useless because of the Union's naval blockade of Galveston, Houston, and other ports. (Full article...)

The Utah Territory (September 9, 1850 - January 4, 1896) during the American Civil War was far from the main operational theaters of war, but still played a role in the disposition of the United States Army, drawing manpower away from the volunteer forces and providing its share of administrative headaches for the Lincoln Administration. Although no battles were fought in the territory, the withdrawal of Union forces at the beginning of the war allowed the Native American tribes to start raiding the trails passing through Utah. As a result, units from California and Utah were assigned to protect against these raids. Mineral deposits found in Utah by California soldiers encouraged the immigration of non-Mormon settlers into Utah. (Full article...)

During the American Civil War, the State of Vermont gave strong support to the Union war effort, raising troops and money. According to Rachel Cree Sherman:

By the spring of 1865 Vermont was devastated, having sent one tenth of its entire population to war, with a loss of over 5,000 lives to battle, wounds, and disease. The state had dedicated nearly $10 million to support the conflict, half of that amount offered up by towns with no expectation of recompense.

The American state of Virginia became a prominent part of the Confederacy when it joined during the American Civil War. As a Southern slave-holding state, Virginia held the state convention to deal with the secession crisis and voted against secession on April 4, 1861. Opinion shifted after the Battle of Fort Sumter on April 12, and April 15, when U.S. President Abraham Lincoln called for troops from all states still in the Union to put down the rebellion. For all practical purposes, Virginia joined the Confederacy on April 17, though secession was not officially ratified until May 23. A Unionist government was established in Wheeling and the new state of West Virginia was created by an act of Congress from 50 counties of western Virginia, making it the only state to lose territory as a consequence of the war. Unionism was indeed strong also in other parts of the State, and during the war the Restored Government of Virginia was created as rival to the Confederate Government of Virginia, making it one of the states to have 2 governments during the Civil War.

In May, it was decided to move the Confederate capital from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia, in large part because, regardless of the Virginian capital's political status, its defense was deemed vital to the Confederacy's survival. On May 24, 1861, the U.S. Army moved into northern Virginia and captured Alexandria without a fight. Most of the battles in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War took place in Virginia because the Confederacy had to defend its national capital at Richmond, and public opinion in the North demanded that the Union move "On to Richmond!" The successes of Robert E. Lee in defending Richmond are a central theme of the military history of the war. The White House of the Confederacy, located a few blocks north of the State Capitol, became home to the family of Confederate leader, former Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis. (Full article...)

The role of Washington Territory in the American Civil War is atypical, as the territory was the most remote from the main battlefields of the conflict. The territory raised a small number of volunteers for the Union Army, who did not fight against the Confederate States Army but instead maintained defensive positions against possible foreign naval or land attacks. Although the Indian Wars in Washington were recent, there were no Indian hostilities within the area of modern Washington, unlike the rest of the western states and territories, during the Civil War. At the start of the American Civil War, modern-day Washington was part of the Washington Territory. On March 3, 1863, the Idaho Territory was formed from that territory, consisting of the entirety of modern-day Idaho, Montana, and all but southwest Wyoming, leaving the modern-day Washington as Washington Territory. (Full article...)

The U.S. state of West Virginia was formed out of western Virginia and added to the Union as a direct result of the American Civil War (see History of West Virginia), in which it became the only modern state to have declared its independence from the Confederacy. In the summer of 1861, Union troops, which included a number of newly formed Western Virginia regiments, under General George McClellan drove off Confederate troops under General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Philippi in Barbour County. This essentially freed Unionists in the northwestern counties of Virginia to form a functioning government of their own as a result of the Wheeling Convention. Before the admission of West Virginia as a state, the government in Wheeling formally claimed jurisdiction over all of Virginia, although from its creation it was firmly committed to the formation of a separate state.

After Lee's departure, western Virginia continued to be a target of Confederate raids. Both the Confederate and state governments in Richmond refused to recognize the creation of the new state in 1863, and thus for the duration of the war the Confederacy regarded its own military offensives within West Virginia not as invasion but rather as an effort to liberate what it considered to be enemy-occupied territory administered by an illegitimate government in Wheeling. Nevertheless, due to its increasingly precarious military position and desperate shortage of resources, Confederate military actions in what it continued to regard as "western Virginia" focused less on reconquest as opposed to both on supplying the Confederate Army with provisions as well as attacking the vital Baltimore and Ohio Railroad that linked the northeast with the Midwest, as exemplified in the Jones-Imboden Raid. Guerrilla warfare also gripped the new state, especially in the Allegheny Mountain counties to the east, where loyalties were much more divided than in the solidly Unionist northwest part of the state. Despite this, the Confederacy was never able to seriously threaten the Unionists' overall control of West Virginia. (Full article...)

With the outbreak of the American Civil War, the northwestern state of Wisconsin raised 91,379 soldiers for the Union Army, organized into 53 infantry regiments, 4 cavalry regiments, a company of Berdan's sharpshooters, 13 light artillery batteries and 1 unit of heavy artillery. Most of the Wisconsin troops served in the Western Theater, although several regiments served in Eastern armies, including three regiments within the famed Iron Brigade. 3,794 were killed in action or mortally wounded, 8,022 died of disease, and 400 were killed in accidents. The total mortality was 12,216 men, about 13.4 percent of total enlistments. (Full article...)

At the time of the American Civil War (1861–1865), Canada did not yet exist as a federated nation. Instead, British North America consisted of the Province of Canada (parts of modern southern Ontario and southern Quebec) and the separate colonies of Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, British Columbia and Vancouver Island, as well as a crown territory administered by the Hudson's Bay Company called Rupert's Land. Britain and its colonies were officially neutral for the duration of the war. Despite this, tensions between Britain and the United States were high due to incidents such as the Trent Affair, blockade runners loaded with British arms supplies bound for the Confederacy, and the Confederate Navy commissioning of the CSS Alabama from Britain.

Canadians were largely opposed to slavery, and Canada had recently become the terminus of the Underground Railroad. Close economic and cultural links across the long border, also encouraged Canadian sympathy towards the Union. Between 33,000 and 55,000 men from British North America enlisted in the war, almost all of them fighting for Union forces. Some press and churches in Canada supported the secession, and some others did not. There was talk in London in 1861–62 of mediating the war or recognizing the Confederacy. Washington warned this meant war, and London feared Canada would quickly be seized by the Union army. (Full article...)