Psychopathography of Adolf Hitler

Psychopathography of Adolf Hitler is an umbrella term for psychiatric (pathographic, psychobiographic) literature that deals with the hypothesis that the German Führer and Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) suffered from a mental illness. During his lifetime, but also far beyond his death Hitler was again and again associated with mental disorders as "hysteria", "psychopathy" or megalomania and paranoid schizophrenia. Among the psychiatrists and psychoanalysts who have diagnosed Hitler with mental disturbance are well-known figures such as Walter C. Langer and Erich Fromm. Other researchers, like Fritz Redlich, have gained in their investigations on the contrary the impression that Hitler was probably not mentally deranged.

Difficulty of psychopathography in general and of Hitler’s psychopathography in particular

Corresponding to the considerable interest that the individuum Hitler still provokes in the general audience, Hitler-psychopathographies are strongly geared towards the media. But in psychiatry, pathography has a bad reputation. Problematic are especially such diagnostics, that have been carried out ex post, without the primary means of diagnostic assessment: the psychiatric exploration, that is the direct examination of the patient.[1] The German psychiatrist Hans Bürger-Prinz (University of Hamburg) went so far to state that any remote diagnostics constitute a “fatal abuse of psychiatry”.[2] The immense range of mental disorders that Hitler has been credited with over time, gives a good idea how error-prone this method is (see table).[3] Another indicator for the quality issues of many of the subsequently mentioned Hitler-pathographies is an either completely missing or grossly abbreviated discussion of the abundance of publications that have already been submitted on this subject by other authors.

| Alleged disorder | Author(s) |

|---|---|

| Hysteria, histrionic personality disorder | Wilmanns (1933), Murray (1943), Langer (1943), Binion (1976), Tyrer (1993) |

| Schizophrenia, paranoia | Vernon (1942), Murray (1943), Treher (1966), Schwaab (1992), Tyrer (1993), Coolidge/Davis/Segal (2007) |

| Psychotic symptoms due to drug abuse | Heston/Heston (1980) |

| Psychotic symptoms due to physical illness | Gibbels (1994), Hesse (2001), Hayden (2003) |

| Psychopathy, antisocial personality disorder | Bychowski (1948), Henry/Geary/Tyrer (1993), Coolidge/Davis/Segal (2007) |

| Narcissistic personality disorder | Sleigh (1966), Bromberg/Small (1983), Coolidge/Davis/Segal (2007) |

| Sadistic personality disorder | Coolidge/Davis/Segal (2007) |

| Borderline personality disorder | Bromberg/Small (1983), Victor (1999), Dorpat (2003), Coolidge/Davis/Segal (2007) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | Dorpat (2003), Koch-Hillebrecht (2003), Vinnai (2004), Coolidge/Davis/Segal (2007) |

| Abnormal brain lateralization | Martindale/Hasenfus/Hines (1976) |

| Schizotypal personality disorder | Rappaport (1975), Waite (1977) |

| Dangerous leader disorder | Mayer (1993) |

| Bipolar disorder | Hershman/Lieb (1994) |

| Asperger syndrome | Fitzgerald (2004) |

In the case of Hitler, psychopathography poses particular problems. First, authors who write about Hitler's most personal matters have to deal with the threat that a possibly voyeuristic readership uncritically accepts even the most sparsely proven speculations – such as for example happened in the case of Lothar Machtan’s book The Hidden Hitler (2001).[4] Even more grave, secondly, is the warning put forward by some authors that pathologizing Hitler would inevitably mean to discharge him of at least some of his responsibility.[5] Others have feared that by pathologizing or demonizing Hitler on the contrary all the blame could easily be relocated on the mad dictator, while the misguided "masses" and the power elites who had been working him would be relieved.[6] Famed is Hannah Arendt’s word of the "banality of evil"; in 1963, she ruled that for a Nazi perpetrator as Adolf Eichmann, mental normality and the ability to mass murder were not mutually exclusive.[7] Some authors were fundamentally opposed to any attempt to explain Hitler, for example by psychological means.[8] The furthest went Claude Lanzman, who described such attempts as "obscene"; after the completion of his film Shoah (1985) he felt them as bordering Holocaust denial and attacked them sharply. He especially criticized the historian Rudolph Binion.[9]

As the psychiatrist Jan Ehrenwald has pointed out, the question often has been neglected as how a possibly mentally ill Hitler could have been able to win those millions of enthusiastic followers that supported his policy until 1945.[10] Daniel Goldhagen argued in 1996 that Hitler's political ascent was not so much made possible by his psychopathology, but rather by the precarious social conditions that existed at that time in Germany.[11] Some authors have on the contrary noted that cases of people like Charles Manson or Jim Jones have been described who suffered from illness as crippling as schizophrenia, but nonetheless found a crowd of followers on whom they succeeded to have a tremendous influence.[12] Early on, the view was expressed, too, that Hitler was able to handle his psychopathology quite skillfully, even aware how he could use his symptoms to effectively steer the emotions of his audience.[13] Still other authors have suggested that Hitler's followers themselves were mentally disturbed;[14] evidence for this claim however could not be brought by.[15] The question how Hitler's individual psychopathology might have been linked with the enthusiasm of his followers was first discussed in 2000 by the interdisciplinary team of authors Matussek/Matussek/Marbach.[16]

Hysteria

Hitler in Pasewalk military hospital (1918)

It has not yet been established whether Hitler was ever examined by a psychiatrist. Oswald Bumke, psychiatrist and contemporary of Hitler's, assumed that this was never the case.[17] The only psychiatrist whom Hitler demonstrably met personally – the Munich Professor Kurt Schneider – was not Hitler's physician.[18] While medical documents that allow conclusions about Hitler's physical health have been found and made accessible for research (also see Adolf Hitler#Health), there is a complete lack of original documents that would allow for an assessment of Hitler’s mental condition.[19]

Speculations about a possible psychiatric evaluation Hitler in his lifetime focus on his stay in a military hospital Pasewalk end of 1918. Hitler came to this hospital after a mustard gas poisoning that he contracted in a defensive battle in Flanders. In Mein Kampf, he mentions this hospital stay in connection with its painful temporary blindness, and with the "misfortune" and "madness" of the German Revolution of 1918–19 and of the German War defeat, both of which he learned about during his recovery, and what triggered a renewed blindness. Hitler as well as his early biographers took great notice of this strong physical response to the historic events, because the relapse into blindness identified the turning point in which Hitler felt the vocation to become a politician and Germany's savior.[20]

However, already in Hitler’s lifetime some psychiatrists judged that such a relapse without organic explanation must be described as hysterical symptom.[21] The hysteria diagnosis had its greatest popularity with Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis, but was still in use in the 1930s and 1940s. Loss of the sense organs were among typical symptoms, in addition to a self-centered and theatrical behavior. So had the distinguished psychiatrist Karl Wilmanns supposedly expressed in a lecture: "Hitler has had a hysterical reaction after being buried alive in the field"; Wilmann then lost his position in 1933.[22] His assistant Hans Walter Gruhle suffered professional disadvantages due to similar statements.[23] In modern psychiatry, the term "hysteria" is no longer in use; today, corresponding symptoms are rather being associated with dissociative disorder or histrionic personality disorder.

Little is known about Hitler's hospital stay. It isn’t even beyond question what complaints were found on him. Hitler’s medical record from Pasewalk that could confirm or refute a diagnosis was considered lost already in the late 1920s; it didn’t reappear ever since.[5][24] However, the authors of the most recent edition of the anthology Genie, Irrsinn und Ruhm (1992) took the liberty to specify that Hitler was not only diagnosed with physical ailments (Parkinson's disease, encephalitis resp. syphilis with blindness), but with a whole cluster of psychiatric problems, too, such as a paranoid personality, narcissistic and "hysterical" psychopathy with hysterical blindness or hysterical paresis, schizoid personality disorder and even schizophrenia with paranoia and megalomania; evidence was not listed though.[25]

A Psychiatric Study of Hitler (1943)

During World War II, the United States intelligence agency OSS collected information about Hitler's personality, and commissioned in 1943 a research team led by Walter C. Langer to develop psychological reports.[26] In one of these reports, titled A Psychiatric Study of Hitler, was the hypothesis developed that Hitler was treated in Pasewalk by the psychiatrist Edmund Forster, who had in 1933 committed suicide for fear of reprisals. Starting point of this report was a testemony of the psychiatrist Karl Kroner who also worked in the hospital in 1918. Kroner confirmed in particular that Forster had examined Hitler and that he had diagnosed him with "hysteria".[27] The report was held under lock, but in the early 1970s rediscovered by the American Hitler-biographer John Toland.[28]

I, the Eye Witness (1963)

In 1939, the Austrian physician and writer Ernst Weiss who lived in France in exile wrote a novel, Ich, der Augenzeuge (“I, the eye witness”), a fictional autobiography of a doctor who cured a “hysterical” soldier A. H. from Braunau who had lost his eyesight in the trenches. The plot is set in a Reichswehr hospital at the end of 1918. Since his knowledge could be dangerous to the Nazis, the (fictional) physician is placed in a concentration camp in 1933 and released only after he surrenders the medical records.

Ernst Weiss, the author, committed suicide after the entry of German troops in Paris. He was Jewish and had feared to be deported. His novel was published in 1963. Weiss's knowledge of Hitler's hospital stay was believed to have come from the contemporary biographical literature.[29] Perhaps he had met the likewise exiled Hitler biographer Konrad Heiden in Paris.[30] Only later did the hypothesis emerge that Weiss’s portrayal of Hitler's mental disorder and healing was not a fantasy, but based on insider knowledge. Until today, evidence for this assumption could not be brought forward.[5]

Speculations stacked on speculations

Starting at the assumptions of the intelligence report and following Weiss’s novel, a series of researchers and authors have, consecutively, developed the mere suspicions about a possible involvement of Forster into a supposedly securely established hypnotherapy.[5] These reconstructions are questionable not only because they don’t provide any new evidence; they also exclude alternative interpretations from the outset, widely disregard the historical context, and overlook even that Forster held a view of hysteria that would have led him to other methods of treatment than hypnosis.[31]

- Rudolph Binion, a historian at Brandeis University, considers the supposed hysteria diagnosis for a fallacy; in his 1976 book Hitler among the Germans, he picked the secret service suspicions up and expanded them, however. Binion assumed that Weiss had met Forster in person and received from him a copy of the medical record on which his novel then was based. Following the novel, Binion then assumes that Forster subjected the blind, fanatical Hitler to a suggestion treatment, and later, after being suspended from the civil service and in fear of persecution by the Gestapo, took his own life.[32] The only evidence for these assumptions is construed from Forster’s legacy, while there isn’t even proof of what sort of contact Forster had with Hitler.[24]

- In 1998, David E. Post, a forensic psychiatrist at Louisiana State University, published a paper in which the hypothesis that Forster had treated Hitler’s supposed hysteria with hypnosis was depicted as a proven fact. Post did not include any documented own research.[33]

- Partially inspired by Binion, the British neuropsychologist David Lewis published his book The Man Who Invented Hitler (2003), in which he portrayed Forster’s hypnosis treatment not only as a historical fact, but also as a reason why Hitler turned from an obedient World War soldier into a strong-willed, charismatic politician. In this book, Forster is being stylized as the "creator" of Hitler.[34]

- Another book that is inspired by Binion was published by Manfred Koch-Hillebrecht, a German psychologist and professor emeritus of politics at the University of Koblenz: Hitler. Ein Sohn des Krieges (2003). Koch-Hillebrecht tried to prove that Hitler suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and describes how Forster subjected his alleged patient to shock therapy in order to make him able to fight again in combat.[35]

- Also in Germany in 2004, the lawyer Bernhard Horstmann published his book Hitler in Pasewalk in which he describes how Forster had healed Hitler with a "brilliantly" used hypnosis not only from his hysterical blindness, but also endowed him with the feeling of omnipotence and the sense of mission that became so characteristic for Hitler as a politician. In this book, no other evidence is put forward as the story of Weiss's novel.[36]

- In 2006, Franziska Lamott, professor of forensic psychotherapy at the University of Ulm, wrote in an article: "[ ... ] as securitized in the medical records of treatment of Corporal Adolf Hitler by the psychiatrist Prof. Edmund Forster, the latter freed him from hysterical blindness using hypnosis".[37]

Critique

Critical comments on these speculations appeared early on. But as psychiatry historian Jan Armbruster (University of Greifswald) judged, they were not sufficiently convincing, such as in the case of journalist Ottmar Katz, author of a biography of Hitler's personal physician, Theodor Morell (1982).[5] Katz suggested that Karl Kroner might have had personal reasons to report some untruths: living as a Jewish refugee in Reykjavik and forced to earn his life as a blue-collar worker, Kroner possibly hoped that the U.S. authorities would not only acknowledge him as a key witness but also help him to reestablish his medical practice.[38] A comprehensive plausibility test was finally performed by the Berlin psychiatrist and psychotherapist Peter Theiss-Abendroth in 2008.[39] In 2009, Armbruster carried this analysis forward, dismantled the hypotheses of Hitler’s hysteria diagnosis and hypnotherapy completely, and showed in detail how the story of Hitler’s alleged treatment by Forster became progressively elaborate and detailed between 1943 and 2006, but not due to the evaluation of historical documents, but to continuous addition of narrative embellishments. Furthermore, Armbruster’s work offers the to date most comprehensive critique of the methodological weaknesses of many Hitler pathographies.[5]

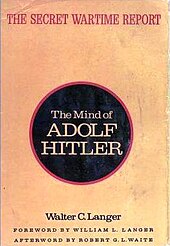

Walter C. Langer (1943)

One of the few authors that stated Hitler showed signs of hysteria without using the Pasewalk episode and Hitler’s alleged treatment by Forster as main evidence, was the American psychoanalyst Walter C. Langer. Langer wrote his study in 1943 on behalf of the OSS.[40] He and his team conducted interviews with many people who were available to the American intelligence services and who knew Hitler personally. They came to the final judgment that Hitler was “a hysterical at the edge of schizophrenia”. The study was for a long time held under lock and published in 1972 under the title The Mind of Adolf Hitler.[41]

Schizophrenia

Already in his lifetime, many elements in Hitler's personal beliefs and conduct were classified by psychiatrists as signs of psychosis or schizophrenia: for example his faith that he was chosen by fate to liberate the German people from their supposedly most dangerous threat: the Jews.

W. H. D. Vernon (1942) and Henry Murray (1943)

One of the first who credited Hitler with the classic symptoms of schizophrenia was the Canadian psychiatrist W.H.D.Vernon; in 1942, he argued in an essay that Hitler was suffering from hallucinations, hearing voices, paranoia and megalomania. Vernon wrote that Hitler’s personality structure – although overall within the range of normal – should be described as leaning towards the paranoid type.[42]

One year later, Henry Murray, a psychologist at Harvard University, developed these views even further. Like Walter C. Langer, Murray wrote his report, Analysis of the Personality of Adolph Hitler, on behalf of the OSS. He came to the conclusion that Hitler, next to hysterical signs, showed all the classic symptoms of schizophrenia: hypersensitivity, panic attacks, irrational jealousy, paranoia, omnipotence fantasies, delusions of grandeur, belief in a messianic mission, and extreme paranoia. He considered him borderlining between hysteria and schizophrenia, but stressed that Hitler possessed considerable control over his pathological tendencies and that he deliberately utilized them in order to stir up nationalist sentiments among the Germans and their hatred against alleged persecutors. Like Walter C. Langer, Murray thought it likely that Hitler eventually would lose faith in himself and in his "destiny", and then commit suicide.[43]

Wolfgang Treher (1966)

The attempt to prove that Hitler had a fully developed psychosis in a clinical sense has only occasionally been made. An example is the book Hitler, Steiner, Schreber (1966) by the Freiburg psychiatrist Wolfgang Treher. Treher explains that both Rudolf Steiner (whose anthroposophy he attributes to mental illness) and Hitler have suffered from schizophrenia.[44] He writes that both managed to stay in touch with reality because they had the opportunity to create their own organizations (Steiner: the Anthroposophical Society; Hitler: the NSDAP and its many subdivisions) that they could influence according to their delusions – and therefore avoid the, normally expected, “schizophrenic withdrawal”. Treher finds that Hitler’s megalomania and paranoia are quite striking.[45]

Edleff Schwaab (1992)

In 1992, German-American clinical psychologist Edleff H. Schwaab published his psychobiography Hitler’s Mind in which he states that Hitler’s imagination – particularly his obsession with the supposed threat posed by the Jews – must be described as the outcome of a paranoia. The cause for this disorder Schwaab suspects to be rooting in a traumatic childhood that was overshadowed by a depressive mother and a tyrannical father.[46]

Paul Matussek, Peter Matussek, Jan Marbach (2000)

The book Hitler – Karriere eines Wahns (2000) is the result from a joint effort of the psychiatrist Paul Matussek, the media theorist Peter Matussek, and the sociologist Jan Marbach, to overcome the tradition of one-dimensional psychiatric pathography and to seek an interdisciplinary approach instead, taking into account socio-historical dimensions, too. This investigation is focussed not so much on Hitler's personal psychopathology, but rather on a description of the interaction between individual and collective factors that accounted for the overall dynamics of the Hitler madness. The book specifies the interplay between Hitler’s leader role (which was charged with psychotic symptoms) on the one hand, and the fascination that this role invoked in his followers on the other hand. The authors conclude that the Nazi crimes had indeed been an expression of madness, but of a madness which was so strongly accepted by the public that the psychotic Hitler and his followers were factually stabilizing each other in their "mad" worldview.[16]

Frederic L. Coolidge, Felicia L. Davis, Daniel L. Segal (2007)

The in terms of methodology most elaborate psychological assessment has been undertaken in 2007 by a research team at the University of Colorado. This study differed from all earlier works by its open, exploratory approach. The team tested systematically which mental disorders Hitler's behavior may have been indicating and which not. It was the first Hitler pathography that was consistently empirical. The psychologists and historians reviewed passed down reports by people who knew Hitler personally, and evaluated these accounts in accordance with a self-developed diagnostic tool that allowed for a wide range of personality, clinical, and neuropsychological disturbances to be measured.[47] According to this study, Hitler showed obvious traits of paranoia, but also of anti-social, sadistic, and narcissistic personality disorders, and distinct traits of posttraumatic stress disorder.[12]

Organically caused psychotic symptoms

Hitler’s alleged psychotic symptoms have repeatedly been attributed to possible organic causes. The psychiatrist Günter Hermann Hesse for example was convinced that Hitler suffered from long-term consequences of the poisoning injury suffered during World War.[48]

Amphetamine abuse

In their 1980 book The Medical Case Book of Adolf Hitler for which they screened an abundance of medical records, the psychiatrist Leonard L. Heston (University of Minnesota) and the nurse Renate Heston report that throughout the last years of his life Hitler regularly took amphetamine, including Pervitin,[49] stimulant drugs with possible side effects such as paranoid delusions.[50]

Syphilis

In the late 1980s, Ellen Gibbels (University of Cologne) had attributed the limb trembling in Hitler’s late years to Parkinson's disease, with wide recognition of the research community. However, some researchers interpreted Hitler’s tremor as a symptom of advanced syphilis, most recently the American historian Deborah Hayden. Hayden links the general paresis from which Hitler in her opinion suffered since 1942, to the mental decline in the last years of his life, especially to his "paranoid temper tantrums."[51] The physcian Frederick Redlich however reported that there is no evidence that suggests that Hitler had syphilis.

Parkinson 's disease

The possibility that Hitler suffered from Parkinson's disease has been investigated first by Ernst-Günther Schenck[52] and later by Ellen Gibbels.[53] In 1994, Gibbels published a paper that pursued the question if Hitler’s nerve disease could also have impaired him mentally.[54]

Psychopathy resp. antisocial personality disorder

Given the inhumanity of his crimes, Hitler has early on been linked with “psychopathy”, a severe personality disorder, whose main symptoms are a great or complete lack of empathy, social responsibility and conscience. The biologically determined concept still plays a role in the psychiatric forensic science, but in the modern medical classification systems (DSM-IV and ICD-10), it is no longer found. Today, corresponding clinical pictures are mostly classified as signs of an antisocial personality disorder. However, the symptomatology is rare, and unlike in popular discourse – where the classification of Hitler as a “psychopath” is a commonplace[55] –, psychiatrists have only occasionally endeavored to associate him with psychopathy or antisocial personality disorder.

Gustav Bychowski (1948)

Early on, some Hitler pathographies took not only psychological, but also historical and sociological aspects into account. This interdisciplinary approach had been developed by the psychiatrist Wilhelm Lange-Eichbaum back in 1928.[56] The earliest socio-psychological pathography of Hitler appeared in 1948 in Gustav Bychowski anthology Dictators and Disciples.[57] In this volume, Bychowski, a Polish-American psychiatrist, compared several historical figures who have successfully carried out a coup d’etat: Julius Caesar, Oliver Cromwell, Robespierre, Hitler and Josef Stalin. He came to the conclusion that all of these men had an abundance of traits that must by classified as “psychopathic” such as the tendency to act out impulses or to project their own hostile impulses onto other people or groups.[58]

Desmond Henry, Dick Geary, Peter Tyrer (1993)

In 1993, the interdisciplinary team Desmond Henry, Dick Geary, and Peter Tyrer published an essay in which they expressed their common view that Hitler had suffered from antisocial personality disorder as defined in ICD-10. The psychiatrist Tyrer was convinced that Hitler furthermore showed signs of paranoia and of histrionic personality disorder.[59]

Depth psychological approaches

While psychiatrically oriented authors, when dealing with Hitler, were primarily endeavoring to diagnose him with a specific clinical disorder, some of their colleagues who follow a depth psychological doctrine as the psychoanalytic school of Sigmund Freud, were first and foremost interested in explaining his monstrously destructive behavior. In accordance to these doctrines, they assumed that Hitler’s behavior and the development of his character were propelled by unconscious processes that were rooted in his earliest years. Pathographies that are inspired by depth psychology, typically attempt to reconstruct the scenario of Hitler's childhood and youth. Occasionally, authors such as Gerhard Vinnai started out with a depth psychological analysis, but then advanced far beyond the initial approach.

Erich Fromm (1973)

Among the most famous Hitler pathographies is Erich Fromm’s 1973 published book Anatomy of Human Destructiveness. Fromm’s goal was it to determine the causes of human violence. He took his knowledge of the person of Hitler from several sources such as the memoir of Hitler’s boyhood friend August Kubizek (1953), Werner Maser’s Hitler-biography (1971), and, most important, a paper by Bradley F. Smith about Hitler's childhood and youth (1967).[60]

Fromm’s pathography follows largely Sigmund Freud's concept of psychoanalysis and states that Hitler was an immature, self-centered dreamer who did not overcome his childish narcissism; as a result of his lack of adaptation to reality he was exposed to humiliations which he tried do overcome by means of lust-ridden destructiveness ("necrophilia"). The evidence of this desire to destroy – including the so-called Nero Decree – was so outrageous that one must assume that Hitler had not only acted destructively, but was driven by a “destructive character”.[61]

Helm Stierlin (1975)

In 1975, the German psychoanalyst and family therapist Helm Stierlin published his book Adolf Hitler. Familienperspektiven, in which he raised the question of the psychological and motivational bases for Hitler's aggression and passion for destruction, similarly to Fromm. His study focusses heavily on Hitler’s relationship to his mother. Stierlin felt that Klara Hitler had frustrated hopes for herself that she strongly delegated to her son, even though for him, too, they were impossible to satisfy.[62]

Alice Miller (1980)

The Swiss childhood researcher Alice Miller gave Hitler a section in her 1980 published book For Your Own Good. Miller owed her knowledge about Hitler to biographic and pathographic works such as those by Rudolf Olden (1935), Konrad Heiden (1936/37), Franz Jetzinger (1958), Joachim Fest (1973), Helm Stierlin (1975), and John Toland (1976). She is convinced that the family setting in which Hitler grew up was not only dominated by an authoritarian and often brutal father, Alois Hitler, but could be characterized as "prototype of a totalitarian regime". She thinks that Hitler’s hate-ridden and destructive personality, that later made millions of people suffer, emerged under the humiliating and degrading treatment and the beating that he received from his father as a child. Miller believes that the mother, after her three first born children died at an early age, was barely capable to foster a warm relationship to her son. Hitler, who early on identified with the tyrannical father, later transferred the trauma of his parental home onto Germany; his contemporaries followed him willingly because they had experienced a childhood that was very similar.

Miller also pointed out that Johanna Pölzl, the querulent sister of Klara Hitler who lived with the family during Hitler's entire childhood, possibly suffered from a mental disorder. According to witnesses, the “Hanni-Tante” (“Hanni-Aunt”) who died in 1911, was either schizophrenic or mentally retarded.[63]

Norbert Bromberg, Verna Volz Small (1983)

Another depth psychologically inspired Hitler pathography has been submitted in 1983 by the New York psychoanalyst Norbert Bromberg (Albert Einstein College of Medicine) and the writer Verna Volz Small.[64] In this book, which is titled Hitler's Psychopathology, Bromberg and Small argue that many of Hitler's personal self-manifestations and actions were to be regarded as an expression of a serious personality disorder. On examination of his family background, his childhood and youth and of his behavior as an adult, as a politician and ruler, they found many clues that Hitler was in line both with the symptoms of a narcissistic personality disorder and of a borderline personality disorder (see also below). Bromberg and Small’s work has been criticized for the unreliable sources that it is based on, and for its speculative treatment of Hitler’s presumed homosexuality.[65] (See also: Sexuality of Adolf Hitler, The Pink Swastika.)

The opinion that Hitler had narcissistic personality disorder was not new; Alfred Sleigh had already represented it in 1966.[66]

Béla Grunberger, Pierre Dessuant (1997)

The French psychoanalyst Béla Grunberger and Pierre Dessuant have included a section about Hitler into their 1997 book Narcissisme, christianisme, antisémitisme. Like Fromm, Bromberg and Small, they were particularly interested in Hitler's narcissism, which they tried to trace by a detailed interpretation of Hitler's alleged sexual practices and constipation problems.[67]

George Victor (1999)

The psychotherapist George Victor had special interest in Hitler’s antisemitism. In his 1999 book Hitler: The Pathology of Evil Hitler, he assumed that Hitler was not only obsessed with hatred of Jews, but with self-hatred, too, and that he suffered from serious (borderline) personality disorder. Victor found that all these problems had their origin in the abuse that he experienced as a child by his father – who, as he believed, were of Jewish descent.[68] (See also Alois Hitler#Biological father.)

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Although it is generelly undisputed that Hitler had formative experiences as a front soldier in World War I, only in the early 2000s psychologists came up with the consideration that at least some of his psychopathology may be attributed to war trauma.

Theodore Dorpat (2003)

In 2003, Theodore Dorpat, a resident psychiatrist in Seattle, published his book Wounded Monster in which he credited Hitler with complex post-traumatic stress disorder. He assumed that Hitler not only experienced war trauma, but – due to physical and mental abuse by the father and the parental failure of the depressed mother – chronic childhood trauma, too. Dorpat is convinced that Hitler showed signs of this disturbance already at the age of 11 years. Both traumas explain why Hitler were prepared neither for social nor for intellectual or professional aspirations. According to Dorpat, many of Hitler’s personality traits – such as his volatility, his malice, the sadomasochistic nature of his relationships, his human indifference and his avoidance of shame – can be traced back to trauma.[69]

In the same year, the above-mentioned German psychologist Manfred Koch-Hillebrecht, too, had come forward with the assumption that Hitler had posttraumatic stress disorder from his war experiences.

Gerhard Vinnai (2004)

In the subsequent year, the social psychologist Gerhard Vinnai (University of Bremen), came to similar conclusions. When writing his work Hitler – Scheitern und Vernichtungswut (2004; “Hitler – Failing and rage of destruction”), Vinnai had a psychoanalytic point of depart; he first subjected Hitler’s book Mein Kampf a depth psychological interpretation and tried to reconstruct how Hitler had processed his experiences in World War I against the background of his childhood and youth. But similar to Dorpat, Vinnai explains the destructive potential in Hitler's psyche not so much as a result of early childhood experiences, but rather due to trauma that Hitler had suffered as a soldier in World War I. Not only Hitler, but a substantial part of the German population was affected by such war trauma. Vinnai then leaves the psychoanalytical discourse and comments on social psychological questions, such as how Hitler’s political world view could have emerged from his trauma and how this could appeal to large numbers of people.[70]

In 2007, the above mentionened authors Coolidge, Davis, and Segal, too, assumed that Hitler suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder.

Minority opinions

Hypotheses like the ones that Hitler's personality and behavior pointed to a personality disorder, to a posttraumatic stress disorder or to schizophrenia have not been undisputed, but they have repeatedly found endorsement from fellow psychiatrists. This does not apply to the following Hitler-pathographies who’s authors are largely left alone with their diagnoses.

Abnormal brain lateralization: Colin Martindale, Nancy Hasenfus, Dwight Hines (1976)

In a 1976 published essay, the psychiatrists Colin Martindale, Nancy Hasenfus, and Dwight Hines (University of Maine) suggested that Hitler had suffered from a sub-function of the left hemisphere of the brain. They referred to the tremor of his left limbs, his tendency for leftward eye movements and the alleged missing of the left testicle. They believed that Hitler’s behavior was dominated by his right cerebral hemisphere, a situation that resulted in symptoms such as a tendency to the irrational, auditory hallucinations, and uncontrolled outbursts. Martindale, Hasenfus and Hines even suspected that the dominance of the right hemisphere contributed to the two basic elements of Hitlers political ideology: antisemitism and Lebensraum ideology.[71]

Schizotypal personality disorder: Robert G. L. Waite (1977)

Robert G. L. Waite, a psychohistorian at Williams College, has been working towards an interdisciplinary exploration of Nazism since 1949, combining historiographical and psychoanalytic methods. In 1977, he published his study The Psychopathic God in which he took the view that Hitler's career can not be understood without considering his pathological personality. Waite assumed that Hitler suffered from schizotypal personality disorder, a condition that at that time was referred to as “borderline personality disorder”. The term received its present meaning only at the end of the 1970s. Until then, “borderline personality disorder” referred to a disorder in the border area of neurosis and schizophrenia, for which Gregory Zilboorg had also coined the term "ambulatory schizophrenia".[72] As cues that Hitler had this condition, Waite specified Hitler’s Oedipus complex, his infantile phantasy, his volatile inconsistency and his alleged coprophilia and urolagnia.[73] Waite’s view partially corresponds with that of the Vienna psychiatrist and Buchenwald survivor Ernest A. Rappaport, who already in 1975 hat called Hitler an "ambulatory schizophrenic".[74]

Dangerous Leader Disorder: John D. Mayer (1993)

The personality psychologist John D. Mayer (University of New Hampshire) published an essay in 1993 in which he suggested an independent psychiatric category for destructive personalities like Hitler: A dangerous leader disorder (DLD). Mayer identified three groups of symptomatic behavioral singularities: 1. indifference (becoming manifest for example in murder of opponents, family members or citizens, or in genocide); 2. intolerance (practicing press censorship, running a secret police or condoning torture); 3. self-aggrandizement (self-assessment as a "unifier" of a people, overestimation of the own military power, identification with religion or nationalism or proclamation of a "grand plan"). Mayer compared Hitler to Stalin and Saddam Hussein; stated aim of this proposition of a psychiatric categorization was to provide the international community with a diagnostic instrument which would make it easier to recognize dangerous leader personalities in mutual consensus and to take action against them.[75] (See also Toxic leader.)

Bipolar disorder: Jablow Hershman, Julian Lieb (1994)

In 1994, the writer Jablow Hershman and the psychiatrist Julian Lieb published their joint book A Brotherhood of Tyrants. Based on known Hitler biographies, they developed the hypothesis that Hitler – just like Napoleon Bonaparte and Stalin - was not only manic-depressive, but that it had just been his disorder that had driven him into politics and then made him dictator. While many manic depressives end in psychiatry, others may be propelled by the same disturbance to seek political power. Once they succeed, they show features of psychotic tyranny such as exaggerated self-confidence and megalomania.[76]

Asperger syndrome: Michael Fitzgerald (2004)

Since 1991, one of the most prolific authors of psychopathographies is the Irish professor of child and adolescent psychiatry Michael Fitzgerald. Inspired by his autism studies, he published a cornucopia of pathographies of outstanding historical personalities, mostly disclosing that they had Asperger syndrome. In his 2004 published anthology Autism and creativity, he classified Hitler as an “autistic psychopath”. Autistic psychopathy is a term that the Austrian physician Hans Asperger had coined in 1944 in order to label the clinical picture that was later named after him: the Asperger syndrome, a variety of childhood autism; it has nothing to with psychopathy in the sense of an antisocial personality disorder. Fitzgerald appraised many of Hitler’s publicly known traits as downright autistic, particularly his various obsessions, his lifeless gaze, his social awkwardness, his lack of interest in women, his lack of personal friendships and his tendency to monologue-like speeches which according to Fitzgerald resulted from a disability to have real conversations.[77]

Critique

Pathographies are by definition works on personalities which the author believes to be mentally disturbed. Psychiatrists deal with mental illness and usually write no specialist publications on those they consider to be mentally healthy. Exceptions occur at most within professional discourses in which individual authors confront the positions of colleagues, who, in the opinion of the former, are at fault to classify a certain personality as mentally ill. As a result, works that advance the view that a particular personality was mentally healthy, are naturally underrepresented in the overall corpus of pathographic literature. This applies to the psychopathography of Adolf Hitler, too.

Some authors have described Hitler as a cynical manipulator or a fanatic, but denied that he was seriously mentally disturbed; among them are the British historians Ian Kershaw, Hugh Trevor-Roper, Alan Bullock, and A. J. P. Taylor, and, more recently, the German psychiatrist Manfred Lütz.[78] Ian Kershaw has concluded that Hitler had no major psychotic disorders and was not clinically insane.[79] The American psychologist Glenn D. Walters wrote in 2000: "Much of the debate about Hitler's long-term mental health is probably questionable, because even if he had suffered from significant psychiatric problems, he attained the supreme power in Germany rather in spite of these difficulties than through them."[80]

Erik H. Erikson (1950)

The psychoanalyst and developmental psychologist Erik Erikson has given Adolf Hitler a chapter in his 1950 book, Childhood and Society. Erikson referred to Hitler as an "histrionic and hysterical adventurer" and discovered evidence of an undissolved Oedipus complex in his self-portrayals. Nonetheless, he pointed out that Hitler was such an actor that his self-expression could not be measured with conventional diagnostic tools. Although Hitler had possibly been showing certain psychopathology, he dealt with this in an extremely controlled fashion and utilized it purposefully.[81]

Terry L. Brink (1974)

Terry Brink, a student of Alfred Adler, published an essay The case of Hitler (1975) in which he, similar to the above-mentioned authors, concluded that after a conscientious evaluation of all records there is not sufficient evidence that Hitler had a mental disorder. Many of Hitler's behavior must be understood as attempts to overcome a difficult childhood. However, many of the documents and statements that have been quoted in order to proof a mental illness were to be considered untrustworthy. Too strong consideration has been give for example to allied propaganda and to fabrications of people who have tried to distance themselves from Hitler for personal reasons.[82]

Frederick Redlich (1998)

One of the most comprehensive Hitler pathographies comes from the neurologist and psychiatrist Frederick Redlich.[83] Redlich, who emigrated from Austria in 1938 to the United States, is considered one of the founders of American social psychiatry. In his 1998 published work Hitler: Diagnosis of a Destructive Prophet, on which he worked for 13 years, Redlich came to believe that Hitler had indeed shown enough paranoia and defense mechanisms in order to ”fill a psychiatric textbook with it”, but that he was probably not mentally disturbed. Hitler’s paranoid delusions ”could be seen as symptoms of a mental disorder, but the largest part of the personality worked normal.” Hitler ”knew what he was doing and he did it with pride and enthusiasm.”[84]

Hans-Joachim Neumann, Henrik Eberle (2009)

After two years of study – of the diaries of Theodor Morell among others –, the physician Hans-Joachim Neumann and the historian Henrik Eberle published in 2009 their joint book War Hitler krank? (“Was Hitler sick?”), in which they concluded: ”For a medically objectified mental illness of Hitler there is no evidence”.[85]

Publications

Summaries

- Armbruster, Jan. Die Behandlung Adolf Hitlers im Lazarett Pasewalk 1918: Historische Mythenbildung durch einseitige bzw. spekulative Pathographie (PDF; 776 kB). In: Journal für Neurologie, Neurochirurgie und Psychiatrie 10, 2009, Issue 4, P. 18–22.

- Brunner, José. Humanizing Hitler – Psychohistory and the Making of a Monster. In: Moshe Zuckermann (editor): Geschichte und Psychoanalyse, Tel Aviver Jahrbuch für Geschichte XXXII., Göttingen 2004, P. 148–172.

- Gatzke, Hans W. Hitler and Psychohistory. In: American Historical Review 78, 1973, P. 394 ff.

- Kornbichler, Thomas. Adolf-Hitler-Psychogramme, Frankfurt am Main, 1994. ISBN 3-631-47063-0.

- Rosenbaum, Ron Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of His Evil, Harper Perennial: New York, 1999. ISBN 0-06-095339-X

Pasewalk episode

- Köpf, Gerhard: Hitlers psychogene Erblindung. Geschichte einer Krankenakte. In: Nervenheilkunde, 2005, Volume 24, P. 783–790

Further psychopathographies and psychobiographies of Hitler not mentioned in this article

- Carlotti, Anna Lisa Adolf Hitler. Analisi storica della psicobiografie del dittatore, Milano, 1984.

- Doucet, Friedrich W. Im Banne des Mythos: Die Psychologie des Dritten Reiches, Bechtle: Esslingen, 1979. ISBN 3762803897

- Dobberstein, Marcel. Hitler: Die Anatomie einer destruktiven Seele, Münster 2012.

- Neumayr, Anton. Hitler: Wahnideen – Krankheiten – Perversionen, Pichler: Wien 2001. ISBN 3854312504

- Recktenwald, Johann. Woran hat Adolf Hitler gelitten? Eine neuropsychiatrische Deutung, München, 1963.

- Koch-Hillebrecht. Manfred. Homo Hitler. Psychogramm des deutschen Diktators. Goldmann: München 1999. ISBN 3-442-75603-0.

References

- ^ Hilken, Susanne. Wege und Probleme der Psychiatrischen Pathographie, Karin Fischer: Aachen, 1993

- ^ Bürger-Prinz, Hans. Ein Psychiater berichtet, Hoffmann & Campe, 1971. ISBN 3-455-00740-6

- ^ Wippermann, Wolfgang. Faschismus und Psychoanalyse. Forschungsstand und Forschungsperspektiven. In: Bedrich Loewenstein (Editor). Geschichte und Psychologie. Annäherungsversuche, Pfaffenweiler, 1992. P. 266; Dörr, Nikolas. Zeitgeschichte, Psychologie und Psychoanalyse

- ^ Machtan, Lothar. Hitlers Geheimnis: Das Doppelleben eines Diktators, Fest: Berlin, 2001. ISBN 3828601456; Lothar Machtan: Hitlers Geheimnis perlentaucher.de

- ^ a b c d e f Armbruster, Jan: Die Behandlung Adolf Hitlers im Lazarett Pasewalk 1918: Historische Mythenbildung durch einseitige bzw. spekulative Pathographie . In: Journal für Neurologie, Neurochirurgie und Psychiatrie, Volume 10 (4), 2009, P. 18–22.

- ^ Als ein Volk ohne Schatten! In: Die Zeit, No. 48, November 21, 1986

- ^ Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem. Ein Bericht von der Banalität des Bösen, Piper: München, Zürich, 15th edition, 2006. ISBN 978-3-492-24822-8; to similar conclusions came Harald Welzer in his book Täter. Wie aus ganz normalen Menschen Massenmörder werden, Fischer: Frankfurt, 2005. ISBN 3-10-089431-6; other authors however, as Rolf Pohl and Joachim Perels, are convinced that mass murderers cannot possibly be mentally normal.

- ^ The Jewish theologian and Holocaust survivor Emil Fackenheim, among others, believed that a radical evil such as the evil in Hitler, could not be explained by humans, but only by God, and God kept silent; Emil Fackenheim, Yehuda Bauer: The Temptation to Blame God. In: Rosenbaum, Ron. Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of His Evil. Harper Perennial: New York, 1999. ISBN 0-06-095339-X

- ^ Claude Lanzmann and the War Against the Question Why. In: Rosenbaum (1999), P. 251–266; Lanzmann, Claude. Hier ist kein Warum. In: Stuart Liebman (Editor). Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah: Key Essays, Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-19-518864-0; Lanzmann, Claude; Caruth, Cathy; Rodowick, David. The Obscenity of Understanding. An Evening with Claude Lanzmann. In: American Imago, 48, 1991, P. 473–495

- ^ Jan Ehrenwald. The ESP Experience: A Psychiatric Validation. Basic Books, 1978. ISBN 0-465-02056-9, Section Hitler: Shaman, Schizophrenic, Medium?

- ^ Goldhagen, Daniel. Hitler's Willing Executioners. Alfred Knopf: New York, 1996; Hans-Ulrich Wehler shared the same view: Geschichte als historische Sozialwissenschaft. Frankfurt am Main, 1973, P. 103.

- ^ a b Coolidge, Frederic L.; Davis, Felicia L.; Segal, Daniel L.. Understanding Madmen: A SSM-IV Assessment of Adolf Hitler . In: Individual Differences Research 5, 2007, P. 30–43.

- ^ For example: Murray, Henry A. Analysis of the personality of Adolf Hitler. With predictions of his future behavior and suggestions for dealing with him now and after Germany’s surrender, 1943. Online:„Analysis of the Personality of Adolph Hitler“

- ^ For example Langer: Walter Langer is dead at 82; wrote secret study of Hitler New York Times; A Psychological Profile of Adolf Hitler. His Life and Legend (Online); Eckhardt, William. The Values of Fascism. In: Journal of Social Issues, Volume 24, 1968, P. 89–104; Muslin, Hyman. Adolf Hitler. The Evil Self. In: Psychohistory Review, 20, 1992, P. 251–270; Berke, Joseph. The Wellsprings of Fascism: Individual Malice, Group Hatreds and the Emergence of National Narcissism, Free Associations, Vol. 6, Part 3 (Number 39), 1996; Lothane, Zvi. Omnipotence, or the delusional aspect of ideology, in relation to love, power, and group dynamics. In: American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 1997, Volume 57 (1), P. 25–46

- ^ Psychological evaluations of Nazi leaders didn’t show any signs of mental disturbances (Zillmer, Eric A.; Harrower, Molly; Ritzler, Barry A.; Archer, Robert P. The Quest for the Nazi Personality. A Psychological Investigation of Nazi War criminals. Routledge, 1995. ISBN 0-8058-1898-7)

- ^ a b Matussek, Paul; Matussek, Peter; Marbach, Jan . Hitler – Karriere eines Wahns, Herbig: Munich, 2000. ISBN 3-7766-2184-2; Das Phänomen Hitler; Review; Marbach, Jan. Zum Verhältnis von individueller Schuld und kollektiver Verantwortung. Lecture given on the 35th annual conference of the „Deutschsprachige Gesellschaft für Kunst und Psychopathologie des Ausdrucks e.V.“, October 25. – 28., 2003, Munich

- ^ Bumke, Oswald. Erinnerungen und Betrachtungen. Der Weg eines deutschen Psychiaters, Richard Pflaum: München, 2nd edition, 1953.

- ^ Schneider briefly made Hitler’s aquainance when the latter visited an old and at this time mentally deranged party comrade from the early days of his political activity at the Schwabing Hospital. Public Mental Health Practices in Germany; Schenck, Ernst Günther. Patient Hitler. Eine medizinische Biographie, Droste: Düsseldorf, 1989. ISBN 3-8289-0377-0, P. 514.

- ^ Armbruster (2009); Redlich, Fritz. Hitler. Diagnose des destruktiven Propheten, Werner Eichbauer: Vienna, 2002. ISBN 0-19-505782-1; Schenck, Ernst Günther. Patient Hitler. Eine medizinische Biographie, Verlag Droste, 1989.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf, 13th edition, 1933, P. 220–225.

- ^ Oswald Bumke. Erinnerungen und Betrachtungen. Der Weg eines deutschen Psychiaters. München: Richard Pflaum. 2nd edition 1953; see also Murray (1943)

- ^ Pieper, Werner. Highdelberg: Zur Kulturgeschichte der Genussmittel und psychoaktiven Drogen, 2000, P. 228; Lidz, R.; Wiedemann, H. R. Karl Wilmanns (1873–1945). … einige Ergänzungen und Richtigstellungen. In: Fortschritte der Neurologie, 1989, Volume 57, P. 160–161

- ^ Riedesser, P.; Verderber, A. „Maschinengewehre hinter der Front“. Zur Geschichte der deutschen Militärpsychiatrie, Fischer: Frankfurt/Main, 1996. ISBN 3-935964-52-8

- ^ a b Armbruster, Jan. Edmund Robert Forster (1878–1933). Lebensweg und Werk eines deutschen Neuropsychiaters, Matthiesen: Husum, 2006. ISBN 978-3-7868-4102-9

- ^ Lange-Eichbaum, Wilhelm; Kurth, W. Genie, Irrsinn und Ruhm, Volume 8, 7th edition, 1992, P. 74–91

- ^ Hoffman, Louise E. American psychologists and wartime research on Germany, 1941–1945. In: American Psychologist, Volume 47, 1992, P. 264–273

- ^ Armbruster (2009); Dr. Karl Kroner

- ^ Toland, John. Adolf Hitler: The Definitive Biography, 1976. ISBN 0-385-42053-6

- ^ Ernst Weiß: Der Augenzeuge. Biographie und biographische Darstellungstechnik

- ^ Pazi, Margarita. Ernst Weiß. Schicksal und Werk eines jüdischen mitteleuropäischen Autors in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts, Peter Lang: Frankfurt/Main, 1993. ISBN 3-631-45475-9.

- ^ Forster, Edmund. Hysterische Reaktion und Simulation. In: Monatsschrift für Psychiatrie und Neurologie, Volume 42, 1917, P. 298–324, 370–381; Armbruster (2009)

- ^ Binion, Rudolph. Hitler among the Germans, Elsevier: New York, 1976. ISBN 0-444-99033-X.

- ^ Post, David E. The Hynosis of Adolf Hitler. In: Journal of Forensic Science, November 1998, Volume 43 (6), P. 1127–1132; Armbruster (2009)

- ^ Lewis, David. The man who invented Hitler. The Making of the Führer, London, 2003. ISBN 0-7553-1149-3; Armbruster (2009)

- ^ Koch-Hillebrecht, Manfred. Hitler. Ein Sohn des Krieges. Fronterlebnis und Weltbild, Herbig: Munich, 2003. ISBN 3-7766-2357-8; Hitlers Therapie Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung; Armbruster (2009)

- ^ Horstmann, Bernhard. Hitler in Pasewalk. Die Hypnose und ihre Folgen, Droste: Düsseldorf, 2004. ISBN 3-7700-1167-8; Der blinde Führer. Bernd Horstmanns Krimi um Hitlers Krankenakte; Review in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung; Armbruster (2009)

- ^ Franziska Lamott. Trauma ohne Unbewusstes? – Anmerkung zur Inflation eines Begriffs. In: Buchholz, M. B.; Gödde, G. (editors). Das Unbewusste in der Praxis. Erfahrungen verschiedener Professionen, Volume 3, Psychosozial-Verlag: Gießen, 2006. ISBN 3-89806-449-2, P. 587–609; cited after: Armbruster (2009)

- ^ Katz, Ottmar. Prof. Dr. Med. Theo Morell. Hitlers Leibarzt., Hestia-Verlag: Bayreuth, 1982. ISBN 3-7770-0244-5

- ^ Theiss-Abendroth, Peter. Was wissen wir wirklich über die militärpsychiatrische Behandlung des Gefreiten Adolf Hitler? Eine literarisch-historische Untersuchung. In: Psychiatrische Praxis, Volume 35, 2008, P. 1–5

- ^ Walter Langer is dead at 82; wrote secret study of Hitler New York Times

- ^ Langer, Walter C. The Mind of Adolf Hitler. The Secret Wartime Report, Basis Books, 1972. ISBN 0-465-04620-7

- ^ Vernon, W. H. D. Hitler, the man – notes for a case history (PDF-Datei; 2,79 MB). In: The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Volume 37, Issue 3, July 1942, P. 295–308; compare Medicus: A Psychiatrist Looks at Hitler. In: The New Republic, April 26th, 1939, P. 326–327.

- ^ Murray, Henry A. Analysis of the personality of Adolf Hitler. With predictions of his future behavior and suggestions for dealing with him now and after Germany’s surrender, 1943. Online:Analysis of the Personality of Adolph Hitler

- ^ Treher, Wolfgang. Hitler, Steiner, Schreber – Gäste aus einer anderen Welt. Die seelischen Strukturen des schizophrenen Prophetenwahns, Oknos: Emmendingen, 1966 (newer edition: Oknos, 1990). ISBN 3-921031-00-1; Wolfgang Treher; Is Wolfgang Treher a reliable author?

- ^ Treher heavily focusses on such statements of Hitler that from the point of “psychological normality” are completely incomprehensive, as for example: “Our dead have all become alive again. Not in spirit they march with us, but alive.” (Treher, P. 157f)

- ^ Schwaab, Edleff H. Hitler’s Mind. A Plunge into Madness, Praeger: Westport, CT, 1992. ISBN 0-275-94132-9

- ^ Coolidge Assessment Battery Manual (doc; 208 kB)

- ^ Hesse, Günter. Hitlers neuropsychiatrischen Störungen. Folgen seiner Lost-Vergiftung?

- ^ Der Spiegel: Hitler An der Nadel, 7/1980, P. 85–87.

- ^ Heston, Leonard L.; Heston, Renate. The Medical Case Book of Adolf Hitler, Cooper Square Press, 2000. ISBN 0-641-73350-X (first published in 1980)

- ^ Deborah Hayden. Pox. Genius, Madness, and the Mysteries of Syphilis. Basic Books. 2003. ISBN 0-465-02881-0; Hitler syphilis theory revived; Heinrich Himmler’s physician, Felix Kersten, allegedly had access to a medical report that was held under lock and supposedly proved that Hitler had syphilis. (Kessel, Joseph. The Man With the Miraculous Hands: The Fantastic Story of Felix Kersten, Himmler’s Private Doctor, Burford Books: Springfield, NJ, 2004. ISBN 1-58080-122-6; see also Hitler the Paretic (Syphilitic)

- ^ Ernst Günther Schenck. Patient Hitler. Eine medizinische Biographie. Verlag Droste. 1989

- ^ Gibbels, Ellen. Hitlers Parkinson-Krankheit: zur Frage eines hirnorganischen Psychosyndroms, Springer: New York, Berlin, 1990. ISBN 3-540-52399-5; to the English speaking world, this hypothesis found admission through Tom Hutton, in 1999 (Hitler’s defeat after Allied invasion attributed to Parkinson’s disease)

- ^ Gibbels, Ellen. Hitlers Nervenkrankheit: Eine neurologisch- psychiatrische Studie. (PDF; 6,87 MB) In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 1994, Volume 42 (2), P. 155–220

- ^ War Hitler krank?

- ^ Lange-Eichbaum, Wilhelm. Genie – Irrsinn und Ruhm, Ernst Reinhardt: Munich, 1928

- ^ Gustav Bychowski, M.D. – 1895-1972

- ^ Bychowski, Gustav. Dictators and Disciples. From Caesar to Stalin: a psychoanalytic interpretation of History, International Universities Press: New York, 1948

- ^ Henry, Desmond; Geary, Dick; Tyrer, Peter. Adolf Hitler. A Reassessment of His Personality Status. In: Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, Volume 10, 1993, P. 148–151

- ^ Smith, Bradley F.. Adolf Hitler. His Family, Childhood and Youth, Stanford, 1967. ISBN 0-8179-1622-9.

- ^ Fromm, Erich. The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, 1973. ISBN 978-0-8050-1604-8

- ^ Stierlin, Helm. Adolf Hitler. Familienperspektiven, Suhrkamp, 1975

- ^ Zdral, Wolfgang. Die Hitlers: Die unbekannte Familie des Führers, 2005, P. 32

- ^ Bromberg, Norbert; Small, Verna Volz. Hitler’s Psychopathology, International Universities Press: New York, Madison/CT, 1983. ISBN 0-8236-2345-9; see also Bromberg, Norbert. Hitler’s Character and Its Development. In: American Imago, 28, Winter 1971, P. 297–298; Norbert Bromberg, 81, Retired Psychoanalyst New York Times; Verna Small, 92, leading Village preservationist

- ^ Review by Michael H. Kater: Hitler’s Psychopathology by Norbert Bromberg, Verna Volz Small. In: Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 1985, Volume 16 (1), P. 141–142

- ^ Sleigh, Alfred. Hitler: A Study in Megalomania. In: Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal, June 1966, Volume 11, Issue 3, P. 218–219

- ^ Grunberger, Béla; Dessuant, Pierre. Narcissisme, christianisme, antisémitisme : étude psychanalytique, Actes Sud: Arles, 1997. ISBN 9782742712618 (Review); Grunberger, Béla. Der Antisemit und der Ödipuskomplex, in: Psyche, Volume 16, Issue 5, January 1962, P. 255-272

- ^ Victor, George. Hitler: The Pathology of Evil, Potomac Books, 1999. ISBN 1-57488-228-7

- ^ Dorpat, Theodore. Wounded Monster. Hitler’s Path from Trauma to Malevolence, University Press of America, 2003. ISBN 0-7618-2416-2

- ^ Vinnai, Gerhard. Hitler – Scheitern und Vernichtungswut. Zur Genese des faschistischen Täters, Psychosozial-Verlag: Gießen, 2004. ISBN 978-3-89806-341-8; Gerhard Vinnai’s website

- ^ Martindale, Colin; Hasenfus, Nancy; Hines, Dwight. Hitler: a neurohistorical formulation. In: Confinia psychiatrica, 1976, Volume 19, Issue 2, P. 106–116

- ^ Zilboorg, Gregory. Ambulatory Schizophrenias. In: Psychiatry, Volume 4, 1941, P. 149–155

- ^ Waite, Robert G. L. ' The Psychopathic God: Adolf Hitler, Basic Books, 1977. ISBN 0-465-06743-3; Waite, Robert G. L. Adolf Hitler’s Anti-Semitism. A Study in History and Psychoanalysis. In: Wolman, Benjamin B. (editor). The Psychoanalytic Interpretation of History, New York, London 1971, P. 192–230.

- ^ Rappaport, Ernest A. Anti-Judaism. A psychohistory, Perspective Press: Chicago, 1975. ISBN 0-9603382-0-9

- ^ Mayer, John D. The emotional madness of the dangerous leader. In: Journal of Psychohistory, Volume 20, 1993, P. 331–348

- ^ Hershman, D. Jablow; Lieb, Julian. A Brotherhood of Tyrants: Manic Depression and Absolute Power, Prometheus Books: Amherst, NY, 1994. ISBN 0-87975-888-0

- ^ Fitzgerald, Michael. Autism and creativity: is there a link between autism in men and exceptional ability?, Routledge, 2004. ISBN 1-58391-213-4. S. 25–27

- ^ Trevor-Roper, Hugh: The Last Days of Hitler, Macmillan, 1947; Bullock, Alan. Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, London, 1952; Taylor, A. J. P. The Origins of the Second World War, Simon & Schuster, 1996. ISBN 0-684-82947-9 (First published in 1961); Lütz, Manfred: Irre – wir behandeln die Falschen: Unser Problem sind die Normalen. Eine heitere Seelenkunde, Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2009. ISBN 3-579-06879-2; Manfred Lütz: „Ich kenne keine Normalen“; Kershaw, Ian. Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis, Penguin Books, 2001.

- ^ Ian Kershaw (25 October 2001). Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis. Penguin Books Limited. p. 728. ISBN 978-0-14-192581-3.

- ^ Retranslated from a German translation that cites: Walters, Glenn D. Lifestyle theory: past, present, and future, Nova Science Publishers, 2006. ISBN 1-60021-033-3, P. 43

- ^ Erikson, Erik H. Childhood and Society, W. W. Norton: New York, London, 1963. ISBN 0-393-31068-X (first edition in 1950)

- ^ Brink, Terry L. The case of Hitler: An Adlerian perspective on psychohistory. In: Journal of Individual Psychology, 1975, Volume 21, P. 23–31

- ^ Lavietes, Stuart. Dr. Frederick C. Redlich, 93, Biographer of Hitler. In: The New York Times, 17. Januar 2004 (Obituary).

- ^ Redlich, Fritz. Hitler: Diagnosis of a Destructive Prophet. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-505782-1

- ^ Neumann, Hans-Joachim; Eberle, Henrik. War Hitler krank? Ein abschließender Befund, Bastei Lübbe: Bergisch Gladbach, 2009. ISBN 3785723865, P. 290; War Hitler krank? Focus online, October 7th, 2009; Hitler war nicht geisteskrank – medizinisch gesehen Welt online, Dezember 2nd, 2009