Attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan

The Reagan assassination attempt occurred on March 30, 1981, just 69 days into the presidency of Ronald Reagan. While leaving a speaking engagement at the Washington Hilton Hotel in Washington, D.C., President Reagan and three others were shot and wounded by John Hinckley, Jr.. Reagan suffered a punctured lung, but prompt medical attention allowed him to recover quickly despite his age.

Reagan was the first serving United States president to survive being shot in an assassination attempt. No formal invocation of presidential succession took place, although a controversial statement by Secretary of State Alexander Haig that he was "in control here" marked a short period during which Vice President George H. W. Bush was physically absent, flying back to Washington, D.C. aboard Air Force Two from a speech in Fort Worth, Texas. Hinckley was found not guilty by reason of insanity and has remained confined to a psychiatric facility.

Motivation

The motivation behind Hinckley's attack was an obsession with actress Jodie Foster. While living in Hollywood in the late 1970s, he saw the film Taxi Driver at least 15 times, apparently identifying strongly with Travis Bickle, the lead character.[1][2] The arc of the story involves Bickle's attempts to protect a 12-year-old prostitute, played by Foster; toward the end of the film, Bickle attempts to assassinate a United States Senator who is running for president. Over the following years, Hinckley trailed Foster around the country, going so far as to enroll in a writing course at Yale University in 1980 when he learned that she was a student there after reading an article in People magazine.[3] He wrote numerous letters and notes to her in late 1980.[4] He called her twice and refused to give up when she indicated that she was not interested in him.[2] Convinced that by becoming a national figure he would be Foster's equal, Hinckley began to stalk then-President Jimmy Carter — his decision to target presidents was also likely inspired by Taxi Driver.[5] He wrote three or four more notes to her in early March 1981. Foster gave these notes to her dean, who gave them to the Yale police department, which sought to track Hinckley down but failed.[6][7]

Ambush outside hotel

Speaking engagement at the Washington Hilton Hotel

Hinckley arrived in Washington, D.C. on Sunday, March 29, getting off a Greyhound Lines bus[8] and checking into the Park Central Hotel.[3] He had breakfast at McDonald's the next morning, noticed U.S. President Ronald Reagan's schedule on page A4 of the Washington Star, and decided it was time to make his move.[9] Knowing that he might not live to tell about shooting Reagan, Hinckley wrote (but did not mail) a letter to Foster about two hours prior to the assassination attempt, saying that he hoped to impress her with the magnitude of his action.[10]

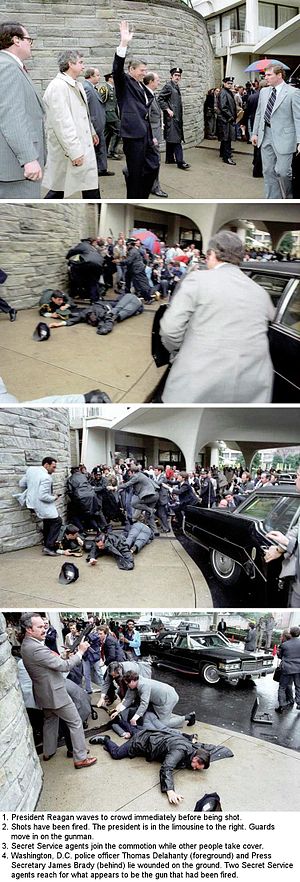

On March 30, 1981, Reagan delivered a luncheon address to AFL-CIO representatives at the Washington Hilton Hotel. He entered the building around 13:45, waving to a crowd which included news media, citizens, and Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

The shooting

Shortly before 14:30 EST, as Reagan walked out of the hotel's T Street NW exit toward his waiting car, Hinckley emerged from the crowd of admirers and fired a Röhm RG-14 .22 cal. blue steel revolver six times in three seconds.[11] The first bullet hit White House Press Secretary James Brady in the head.[12] The second hit District of Columbia police officer Thomas Delahanty in the back.[12][13][14] The third overshot the president and hit the window of a building across the street. The fourth hit Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy in the abdomen.[12][13] The fifth hit the bullet-proof glass of the window on the open side door of the president's limousine. The sixth and final bullet ricocheted off the side of the limousine and hit the president in his left armpit, grazing a rib and lodging in his lung, stopping nearly an inch from his heart.[9]

Sixteen minutes after the assassination attempt, the ATF found that the gun had been purchased at Rocky's Pawn Shop in Dallas, Texas.[15] It had been loaded with six "Devastator"-brand .22LR cartridges, which contained small lead azide explosive charges designed to explode on contact. The rounds were not manufactured in the U.S.; any bullet which contained actual explosives would have been classified as an illegal explosive device under U.S. federal law at the time that Hinckley purchased them. All six bullets failed to explode.

The entire incident was captured on video by at least five cameramen, including all of the major broadcast networks. The new Cable News Network had been broadcasting Reagan's speech live moments earlier, and its crew was still inside the hotel. Hinckley asked the arresting officers whether that night's Academy Awards ceremony would be postponed due to the shooting, and indeed it was — it aired the next evening.[5]

Reagan taken to George Washington University Hospital

Moments after the shooting, Reagan was whisked away by the Secret Service agents in the presidential limousine. At first, there was no realization that the President had been wounded; the bullet which struck him entered under his armpit. However, when Secret Service agent Jerry Parr checked him for gunshot wounds, Reagan coughed up bright, frothy blood, indicating that his lung was punctured. Reagan, already in great pain, believed that one of his ribs had cracked when agent Parr pushed him into the limousine. Parr ordered the motorcade to divert to nearby George Washington University Hospital.[16]

Although the emergency room staff had been notified that gunshot victims were incoming, no stretcher was ready. Reagan exited the limousine and was assisted into the emergency room. Complaining of difficulty breathing, Reagan's knees buckled, and he went down on one knee.[16]

The trauma team, led by Dr. Joseph Giordano, treated Reagan with intravenous fluids, oxygen, tetanus toxoid, and chest tubes.[16] When First Lady Nancy Reagan arrived in the emergency room after being informed, he remarked to her, "Honey, I forgot to duck." (borrowing boxer Jack Dempsey's line to his wife the night he was beaten by Gene Tunney).[17]

Significant quantities of blood came out of the chest tubes. The chief of thoracic surgery, Dr. Benjamin L. Aaron, decided to operate because the bleeding persisted. Ultimately, Reagan lost over half of his blood volume.[16]

In the operating room, Reagan remarked, "Please tell me you're all Republicans." Giordano, a liberal Democrat, replied, "We're all Republicans today." The operation lasted about three hours. His post-operative course was complicated by fever, which was treated with multiple antibiotics.[16]

Reagan's staff was anxious for the president to appear to be recovering quickly. The morning after his operation, he signed a piece of legislation. Reagan left the hospital on the 13th day. Initially, he worked two hours a day in the White House. He did not lead a Cabinet meeting until day 26, did not venture outside Washington until day 49, and did not hold a press conference until day 79. Reagan's physician thought recovery was not complete until October.[16]

Reagan had been scheduled to visit Philadelphia on the day of the shooting. While intubated, he scribbled to a nurse, "All in all, I'd rather be in Philadelphia", a reference to the W.C. Fields tagline.[16][17]

Alexander Haig "in control"

Members of the Cabinet, including Secretary of State Alexander Haig, Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, and National Security Advisor Richard Allen, met in the White House Situation Room to discuss various issues, including the availability of a Nuclear Football (which was still in the possession of the Army officer "carrier" with the president for much of the day), the apparent presence of more than the usual number of Soviet submarines off the Atlantic coast, and the presidential line of succession. These meetings were recorded with the participants' knowledge by Allen, and the tapes have since been made public.[18] Upon learning that Reagan was in surgery, Haig declared, "the helm is right here. And that means right in this chair for now, constitutionally, until the vice president gets here."[19]

In fact the Secretary of State is not second in the line of succession but fifth, after the Vice President (at the time, George H. W. Bush), Speaker of the House (at the time, Tip O'Neill) and the President pro tempore of the Senate (at the time, J. Strom Thurmond). Haig was accused, by Weinberger and others, of overstepping his authority.[20][21]

At the same time, a press conference was underway in the White House. One reporter asked deputy press secretary Larry Speakes who was running the government, to which Speakes responded, "I cannot answer that question at this time." Upon hearing Speakes' remark, Haig rushed to the press room, where he made the following controversial statement:

"Constitutionally, gentlemen, you have the president, the vice president and the secretary of state, in that order, and should the president decide he wants to transfer the helm to the vice president, he will do so. As of now, I am in control here, in the White House, pending the return of the vice president and in close touch with him. If something came up, I would check with him, of course."[19]

Hinckley family connections

John Hinckley Jr. is the son of John Hinckley Sr., chairman of the oil company Vanderbilt Energy Corp., one of Vice President George H.W. Bush's larger political and financial supporters in his 1980 presidential primary campaign against Ronald Reagan. Also, John Hinckley Jr.'s older brother, Vanderbilt vice president Scott Hinckley, and the Vice President's son Neil Bush, had a dinner appointment scheduled for the next day.[22]

The Associated Press published the following short note on March 31, 1981:

The family of the man charged with trying to assassinate President Reagan is acquainted with the family of Vice President George Bush and had made large contributions to his political campaign....Scott Hinckley, brother of John W. Hinckley Jr. who allegedly shot at Reagan, was to have dined tonight in Denver at the home of Neil Bush, one of the Vice President's sons....The Houston Post said it was unable to reach Scott Hinckley, vice president of his father's Denver-based firm, Vanderbilt Energy Corp., for comment. Neil Bush lives in Denver, where he works for Standard Oil Co. of Indiana. In 1978, Neil Bush served as campaign manager for his brother, George W. Bush, the Vice President's eldest son, who made an unsuccessful bid for Congress. Neil lived in Lubbock, Texas, throughout much of 1978, where John Hinckley lived from 1974 through 1980.

Aftermath

Reagan's plans for the next month or so were canceled, including a visit to the Mission Control of Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, in April 1981 during STS-1, the first flight of the Space Shuttle. ( He would instead visit during STS-2 that November.) Reagan returned to the Oval Office on April 25, receiving a standing ovation from staff and Cabinet members; referring to their teamwork in his absence, he insisted, "I should be applauding you."[23] His first public appearance was an April 28 speech before the joint houses of Congress to introduce his planned spending cuts, a campaign promise. He received "two thunderous standing ovations", which the New York Times deemed "a salute to his good health" as well as his programs, which the President introduced using a medical recovery theme.[24]

The two law enforcement officers recovered from their wounds, although Delahanty was forced to retire due to his injuries. The attack seriously wounded the President's Press Secretary, James Brady, who sustained a serious head wound and became permanently disabled. Brady remained as Press Secretary for the remainder of Reagan's administration, but this was primarily a titular role. Later, Brady and his wife Sarah became leading advocates of gun control and other actions to reduce the amount of gun violence in the United States. They also became active in the lobbying organization Handgun Control, Inc. – which would eventually be renamed the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence – and founded the non-profit Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence.[25] The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act was passed in 1993 as a result of their work.[26]

Hinckley was found not guilty by reason of insanity on June 21, 1982. The defense psychiatric reports had found him to be insane[27] while the prosecution reports declared him legally sane.[28][29] Following his lawyers' advice, he declined to take the stand in his own defense.[30] Hinckley was confined at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., where he is still being held as of October 2008[update].[3] After his trial, he wrote that the shooting was "the greatest love offering in the history of the world", and did not indicate any regrets.[31]

The not guilty verdict led to widespread dismay,[32][33] and, as a result, the U.S. Congress and a number of states rewrote laws regarding the insanity defense.[34] The old Model Penal Code test was replaced by a test that shifts the burden of proof of insanity from the prosecution to the defendant. Three states have abolished the defense altogether.[34]

Jodie Foster was hounded relentlessly by the media in early 1981 because she was Hinckley's target of obsession. She commented on Hinckley on three occasions: a press conference a few days after the attack, an article she wrote in 1982,[35] and during an interview with Charlie Rose on 60 Minutes II;[36] she has otherwise ended several interviews after the event was mentioned.[37]

The assassination attempt was portrayed in the 2001 film The Day Reagan Was Shot.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Taxi Driver: Its Influence on John Hinckley, Jr.Retrieved 26 February 2007.

- ^ a b Taxi Driver by Denise Noe. Crime Library. Courtroom Television Network, LLC. Retrieved February 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c John W. Hinckley, Jr. Biography - UMKC Law Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ I'll Get You, Foster by Denise Noe. Crime Library. Courtroom Television Network, LLC. Retrieved March 7, 2006.

- ^ a b The American Experience - John Hinckley Jr. by Julie Wolf. Retrieved March 7, 2006.

- ^ Teen-age Actress Says Notes Sent by Suspect Did Not Hint Violence, Matthew L. Wald, New York Times, April 2, 1981. Retrieved February 28, 2007

- ^ Yale Police Searched For Suspect Weeks Before Reagan Was Shot, Matthew L. Wald, New York Times, April 5, 1981. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- ^ A Drifter With a Purpose, by Mike Sager and Eugene Robinson, Washington Post, April 1, 1981. Retrieved February 28, 2007

- ^ a b The Trial of John W. Hinckley, Jr. by Doug Linder. 2001 Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- ^ Letter written to Jodie Foster by John Hinckley, Jr. March 30, 1981. Retrieved February 26, 2007.

- ^ The President is Shot by Denise Noe. Crime Library. Courtroom Television Network, LLC. Retrieved February 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c Feaver, Douglas. "Three men shot at the side of their President", The Washington Post, March 31, 1981.

- ^ a b Hunter, Marjorie. "2 in Reagan security detail are wounded outside hotel", New York Times, March 31, 1981

- ^ Fears of Explosive Bullet Force Surgery on Officer, by Charles R. Babcock, The Washington Post, April 3, 1981

- ^ Guns Traced in 16 Minutes to Pawn Shop in Dallas, Charles Mohr, New York Times, April 1, 1981. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g Medical chronology of President Ronald Reagan's shooting, at doctorzebra.com

- ^ a b "March 30, 1981" Reagan's reflections on the assassination attempt, Ronaldreagan.com. Retrieved March 5, 2007

- ^ Morning Edition - Reagan Tapes

- ^ a b "The Day Reagan Was Shot". CBS News. Viacom Internet Services Inc. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ^ White House Aides Assert Weinberg Was Upset When Haig Took Charge, by Steven R. Weisman, New York Times, April 1, 1981. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ Bush Flies Back From Texas Set To Take Charge In Crisis, by Steven R. Weisman, New York Times, March 31, 1981. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ Bush's Son Was To Dine With Suspect's Brother, by Arthur Wiese and Margaret Downing, The Houston Post, March 31, 1981

- ^ United Press International (April 25, 1981). "Reagan Given Ovation On Returning to Offices". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ Steven R. Weisman (April 29, 1981). "Political Drama Surrounds First Speech Since Attack". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ Brady Campaign Official Website Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ Text of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ Psychologist Says Hinckley's Tests Similar to Those of the Severely Ill, by Laura A. Kiernan, The Washington Post, May 21, 1982. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ John Hinckley's Acts Described as Unreasonable but Not Insane, by Laura A. Kiernan, The Washington Post, June 11, 1982. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ Hinckley Able to Abide by Law, Doctor Says, by Laura A. Kiernan, The Washington Post, June 5, 1982. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ John Hinckley Declines to Take the Stand, by Laura A. Kiernan, The Washington Post, June 3, 1982. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ Hinckley Hails 'Historical' Shooting To Win Love by Stuart Taylor Jr. New York Times. July 9, 1982. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- ^ Verdict and Uproar by Denise Noe. Crime Library. Courtroom Television Network, LLC. Retrieved February 27, 2006.

- ^ Public That Saw Reagan Shot Expresses Shock at the Verdict by Peter Perl, The Washington Post, June 23, 1982. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ a b The John Hinckley Trial & Its Effect on the Insanity Defense by Kimberly Collins, Gabe Hinkebein, and Staci Schorgl. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ^ Why Me?, An Article by Jodie Foster to Esquire Magazine, December 1982. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ Jodie Foster, Reluctant Star 60 Minutes II. 1999. Retrieved April 24, 2007

- ^ Jodie Foster UMKC Law - Jodie Foster, Retrieved March 9, 2007.

External links

- The Trial of John Hinckley Jr. University of Missouri at Kansas City Law School

- The American Experience - John Hinckley Jr. by Julie Wolf.

- Crime Library - The John Hinckley Case by Denise Noe.

- Reagan's reflections on the assassination attempt

- Unedited footage of assassination attempt on Reagan

- CNN interrupts normal programming to report attempted assassination of President Reagan. (Quicktime)

- 1981 - President Ronald Reagan Shot A report from Wayne Cabot of WCBS Newsradio 880 (WCBS-AM New York) Part of WCBS 880's celebration of 40 years of newsradio.