Effects of meditation

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Since the 1950s hundreds of studies on meditation have been conducted, though many of the early studies were flawed and thus yielded unreliable results.[1][2] More recent reviews have pointed out many of these flaws with the hope of guiding current research into a more fruitful path.[3]

Research on the processes and effects of meditation is a growing subfield of neurological research.[4][5] Modern scientific techniques and instruments, such as fMRI and EEG, have been used to see what happens in the bodies of people when they meditate, and how their bodies and brains change after meditating regularly.[4][6][7]

Meditation is a broad term which encompasses a number of practices.

Mindfulness

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

According to a 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of systematic reviews of RCTs, evidence supports the use of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programs to alleviate symptoms of a variety of mental and physical disorders.[8] This review included a combined total of 8683 participants consisting of different patient categories as well as healthy adults and children.[8] A previous study commissioned by the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality found that meditation interventions reduce multiple negative dimensions of psychological stress.[9] However, this study used a highly heterogeneous group of meditation styles and many of the studies included in this review were short term studies. Other systematic reviews and meta-analysis show that mindfulness meditation has several mental health benefits such as bringing about reductions in depression symptoms,[10][11][12] and mindfulness interventions also appear to be a promising intervention for managing depression in youth.[13][14] Mindfulness meditation is useful for managing stress[11][15][16] anxiety,[10][11][16] and also appears to be effective in treating substance use disorders.[17][18][19] Other review studies have shown that mindfulness meditation can enhance the psychological functioning of breast cancer survivors,[20] effective for eating disorders,[21][22] and may also be effective in treating psychosis.[23][24][25]

Singular studies

Studies have also shown that rumination and worry contribute to mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety,[26] and mindfulness-based interventions are effective in the reduction of worry.[26][27]

Mindfulness meditation also appears to bring about favorable structural changes in the brain.[4][6][7] One recent study found a significant cortical thickness increase in individuals who underwent a brief -8 weeks- MBSR training program and that this increase was coupled with a significant reduction of several psychological indices related to worry, state anxiety, depression.[28] Another study describes how mindfulness based interventions target neurocognitive mechanisms of addiction at the attention-appraisal-emotion interface.[18]

Some studies suggest that mindfulness meditation contributes to a more coherent and healthy sense of self and identity, when considering aspects such as sense of responsibility, authenticity, compassion, self-acceptance and character.[29][30]

Mindfulness scales

In the relatively new field of western psychological mindfulness, researchers attempt to define and measure the results of mindfulness primarily through controlled, randomised studies of mindfulness intervention on various dependent variables. The participants in mindfulness interventions measure many of the outcomes of such interventions subjectively. For this reason, several mindfulness inventories or scales (a set of questions posed to a subject whose answers output the subject's aggregate answers in the form of a rating or category) have arisen. Twelve such methods are mentioned by the Mindfulness Research Guide[31] Examples include:

- the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS);

- the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory;

- the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills;

- the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale.[32]

Through the use of these scales - which can illuminate self-reported changes in levels of mindfulness, the measurement of other correlated inventories in fields such as subjective well-being, and the measurement of other correlated variables such as health and performance - researchers have produced studies that investigate the nature and effects of mindfulness. The research on the outcomes of mindfulness falls into two main categories: stress reduction and positive-state elevation.

Brain mechanisms

In 2011, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) released findings from a study in which magnetic resonance images were taken of the brains of 16 participants 2 weeks before and after the participants joined the mindfulness meditation (MM) program by researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital, Bender Institute of Neuroimaging in Germany, and the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Researchers concluded that

..these findings may represent an underlying brain mechanism associated with mindfulness-based improvements in mental health.[33]

The analgesic effect of MM involves multiple brain mechanisms including the activation of the anterior cingulate cortex and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.[34] In addition, brief periods of MM training increases the amount of grey matter in the hippocampus and parietal lobe.[35] Other neural changes resulting from MM may increase the efficiency of attentional control.[36]

Participation in MBSR programmes has been found to correlate with decreases in right basolateral amygdala gray matter density,[37] and increases in gray matter concentration within the left hippocampus.[38]

Attention and Mindfulness

Attention networks and mindfulness meditation

Psychological and Buddhists conceptualisations of mindfulness both highlight awareness and attention training as key components, in which levels of mindfulness can be cultivated with practise of mindfulness meditation.[39] Focused attention meditation and open monitoring meditation are distinct types of mindfulness meditation, and the former relates to directing and maintaining attention on a chosen object (e.g. the breath).[40] Open monitoring meditation does not involve focus on a specific object, and instead awareness is grounded in the perceptual features of one’s environment.

Focused attention meditation is typically practiced first to increase the ability to enhance attentional stability, and awareness of mental states with the goal being to transition to open monitoring meditation practise that emphases the ability to monitor moment by moment changes in experience, without a focus of attention to maintain. Mindfulness meditation may lead to greater cognitive flexibility [41][42]

Neurological processes underlying focused attention meditation

It is considered that focused attention meditation entails the activation of attention networks in the following manner:[43]

- Initially the alerting network of attention is activated involving sustaining attention on a chosen object. It is associated with the right parietal cortex, right frontal cortex and the thalamus [43]

- When mind wandering occurs this relates to activation of the default mode network associated with the following brain areas: the posterior cingulate cortex, posterior lateral parietal/temporal cortices, the cingulate cortex, and the parahippocampal gyrus.[44] This attention network is associated with certain attentional states as introspective thought and daydreaming. Conversely, when de-activated it relates to task-engagement.[45]

- Distraction from the focus of attention is detected by the salience network, and is associated with the task of monitoring the focus of attention. The associated brain regions include the cingulate cortex and the anterior insula [46]

- When a distracting thought grabs the focus of attention away from the chosen object, the executive function network is capable of inhibiting this from being further processed. This network reduces the distractibility of aspects of one’s environment, and is associated with the basal ganglia, lateral ventral cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) [47]

- The orienting network of attention, which controls stimulus selection, involves shifting the focus of attention back to the original object. The superior colliculus and frontal eye fields as well as the temporal parietal junction and the superior parietal cortex are implicated.[48]

Evidence for improvements in three areas of attention

Sustained attention Tasks of sustained attention relate to vigilance and the preparedness that aids completing a particular task goal. Psychological research into the relationship between mindfulness meditation and the sustained attention network have revealed the following:

- Mindfulness meditators have demonstrated superior performance when the stimulus to be detected in a task was unexpected, relative to when it was expected. This suggests that attention resources were more readily available in order to perform well in the task. This was despite not receiving a visual cue to aid performance. (Valentine & Sweet, 1999).

- In a Continuous performance task [49] an association was found between higher dispositional mindfulness and more stable maintenance of sustained attention.

- In an EEG study,[50] the Attentional blink effect was reduced, and P3b ERP amplitude decreased in a group of participants that completed a mindfulness retreat.[51] The incidence of reduced attentional blink effect relates to an increase in detectability of a second target. This may have been due to a greater ability to allocate attentional resources for detecting the second target, reflected in a reduced P3b amplitude.

- A greater degree of attentional resources may also be reflected in faster response times in task performance, as was found for participants with higher levels of mindfulness experience.[52]

Selective attention

- Selective attention as linked with the orientation network, is involved in selecting the relevant stimuli to attend to.

- Performance in the ability to limit attention to potentially sensory inputs (i.e. selective attention) was found to be higher following the completion of an 8-week MBSR course, compared to a one-month retreat and control group (with no mindfulness training).[52] The ANT task is a general applicable task designed to test the three attention networks, in which participants are required to determine the direction of a central arrow on a computer screen.[53] Efficiency in orienting that represent the capacity to selectively attend to stimuli was calculated by examining changes in the reaction time that accompanied cues indicating where the target would occur relative to the aid of no cues.

- Meditation experience was found to correlate negatively with reaction times on a Eriksen flanker task measuring responses to global and local figures. Similar findings have been observed for correlations between mindfulness experience in an orienting score of response times taken from Attention Network Task performance.[54]

Executive control attention Executive control attention include functions of inhibiting the conscious processing of distracting information. In the context of mindful meditation, distracting information would relate to attention grabbing mental events such as thoughts related to the future or past.[40]

- More than one study have reported findings of a reduced Stroop effect following mindfulness meditation training.[41][55][56] The Stroop effect indexes interference created by having words printed in colour that differ to the read semantic meaning e.g. green printed in red. However findings for this task are not consistently found.[57][58] For instance the MBSR may differ to how mindful one becomes relative to a person who is already high in trait mindfulness.[43]

- Using the Attention Network Task (a version of Eriksen flanker task [53] it was found that error scores that indicate executive control performance were reduced in experienced meditators [52] and following a brief 5 session mindfulness training program.[55]

- A neuroimaging study supports behavioural research findings that higher levels of mindfulness are associated with greater proficiency to inhibit distracting information. As greater activation of the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) was shown for mindfulness meditators than matched controls. .

- Following a Stroop test, reduced amplitude of the P3 ERP component was found for a meditation group relative to control participants. This was taken to signify that mindfulness meditation improves executive control functions of attention. An increased amplitude in the N2 ERP component was also observed in the mindfulness meditation group, thought to reflect more efficient perceptual discrimination in earlier stages of perceptual processing.[59]

Emotion regulation and Mindfulness

Approaching emotions in an adaptive way relates to mindful emotion regulation, which aims to decrease avoidance or suppression of emotions, as well as decreasing over-arousal in emotional reactivity in response to events.[60] It is highlighted that emotion regulation is vital to mental stability.[61] Over-involvement with emotions may lead to critical over-analysis of thoughts and emotions, characterising rumination, predictive of poor mental health.[62] Reductions in rumination have been found following Mindfulness meditation practise.[63][64] Under-involvement with addressing difficult emotions -termed avoidance behaviours- also can be problematic [61] as these can bring about maladaptive defences such as denial, suppression, cognitive distortions, development of psychoses, and even substance abuse or self-harm as methods of avoidance.[65][66]

The mechanisms of Mindful emotion regulation

Through the initial foundations of attention control training, the focus of attention can more consciously be directed towards emotions that arise. Mindfulness combines this mechanism with a particular quality of attitudinal element,[67] of acceptance and non-judgemental awareness. This can range from acknowledging ‘tightness in the chest’ or ‘increases in heart rate’ as well as thought content and emotions that arise. Subsequently, during mindfulness meditation, difficult emotions that may arise become paired with a compassionate and accepting attitude,[60][68] which may gradually extinguish the fear of experiencing the emotions and any related thoughts. Mindfulness practise may lead to the development of metacognitive insight [67][69] or decentering.[68][70] These concepts relate the experiencing thoughts as they are, which is changeable and transient, and that they are not characteristic of absolute reality.[60] This may lead to increased cognitive flexibility [71] reflecting in more adaptively and consciously choosing mental content to identify with, rather than habitually responding. Alternatively a balanced and non-elaborative awareness of experience is cultivated,[60][68] that is not as easily disrupted by the magnitude of emotions experienced or provocative external events.

Evidence of mindfulness and emotion regulation outcomes

Emotional reactivity can be measured and reflected in brain regions related to the production of emotions.[72] It can also be reflected in tests of attentional performance, indexed in poorer performance in attention related tasks. The regulation of emotional reactivity as initiated by attentional control capacities can be taxing to performance, as attentional resources are limited [48]

- Patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD) exhibited reduced amygdala activation in response to negative self-beliefs following an MBSR intervention program that involves mindfulness meditation practise [73]

- The LPP ERP component indexes arousal and is larger in amplitude for emotionally salient stimuli relative to neutral.[74][75][76] Individuals higher in trait mindfulness showed lower LPP responses to high arousal unpleasant images. These findings suggest that individuals with higher trait mindfulness were better able to regulate emotional reactivity to emotionally evocative stimuli.[77]

- Participants that completed a 7-week mindfulness training program demonstrated a reduction in a measure of emotional interference (measured as slower responses times following the presentation of emotional relative to neutral pictures). This suggests a reduction in emotional interference.[78]

- Following a MBSR intervention, decreases in social anxiety symptom severity were found, as well as increases in bilateral parietal cortex neural correlates. This is thought to reflect the increased employment of inhibitory attentional control capacities to regulate emotions [79][80]

Controversies in mindful emotion regulation

It is debated as to whether top-down executive control regions such as the Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC),[81] are required [80] or not [73] to inhibit reactivity of the amygdala activation related to the production of evoked emotional responses. Arguably an initial increase in activation of executive control regions developed during mindfulness training may lessen with increasing mindfulness expertise [82]

Changes in the brain

A 6-week mindfulness based intervention was found to correlate with a significant gray matter increase within the precuneus.[83]

Future directions

A large part of mindfulness research is dependent on technology. As new technology continues to be developed, new imaging techniques will become useful in this field. It would be interesting to use real-time fMRI to help give immediate feedback and guide participants through the programs. It could also be used to more easily train and evaluate mental states during meditation itself.[84] The new technology in the upcoming years offers many exciting potentials for the continued research.

An ancient model of the mind known as the Five-Aggregate Model has been proposed as a theoretical resource that could guide mindfulness interventions.[85] This model comprehensively describes moment-to-moment changes that happen in subjective conscious experience.

Research on other types of meditation

Insight (Vipassana) meditation

Insight meditation has been found to be associated with increased cortical thickness.[86]

Sahaja yoga and mental silence

Sahaja yoga meditation has been shown to correlate with particular brain and brain wave activity.[87][88] Some studies have led to suggestions that Sahaja meditation involves 'switching off' irrelevant brain networks for the maintenance of focused internalized attention and inhibition of inappropriate information.[89]

A study comparing practitioners of Sahaja Yoga meditation with a group of non meditators doing a simple relaxation exercise, measured a drop in skin temperature in the meditators compared to a rise in skin temperature in the non meditators as they relaxed. The researchers noted that all other meditation studies that have observed skin temperature have recorded increases and none have recorded a decrease in skin temperature. This suggests that Sahaja Yoga meditation, being a mental silence approach, may differ both experientially and physiologically from simple relaxation.[90] Sahaja meditators scored above peer group for emotional wellbeing measures on SF-36 ratings.[91]

Kundalini yoga

Kundalini yoga meditation research has found that there "appears to produce structural as well as intensity changes in phenomenological experiences of consciousness",[92] and that multiple regions of the brain are active.[citation needed]

Theoria

Fifteen Carmelite nuns came from the monastery to the laboratory to enter a fMRI machine whilst meditating, allowing scientists there to scan their brains using fMRI while they were in a state known as Unio Mystica (and also Theoria).[93] The documentary film Mystical Brain by Isabelle Raynauld examined this study.[94]

Integrative body-mind training

A study involving the participation of a group of college students, who were asked to use a meditation technique called integrative body-mind training (IBMT involves body relaxation, mental imagery, and mindfulness training), concluded that "meditating may improve the integrity and efficiency of certain connections in the brain" through an increase in their number and robustness.[95] Brain scans showed strong white matter changes in the anterior cingulate cortex.[96]

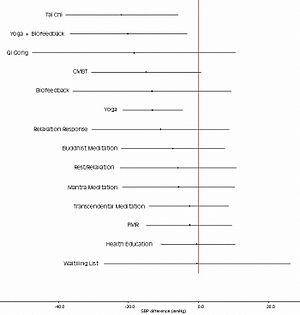

Transcendental

The first Transcendental Meditation (TM) research studies were conducted at UCLA and Harvard University and published in Science and the American Journal of Physiology in 1970 and 1971.[97] However, much research has been of poor quality,[1][98][99] including a high risk for bias due to the connection of researchers to the TM organization and the selection of subjects with a favorable opinion of TM.[100][101][102] Independent systematic reviews have not found health benefits for TM exceeding those of relaxation and health education.[1][98][101] A 2013 statement from the American Heart Association described the evidence supporting TM as a treatment for hypertension as Level IIB, meaning that TM "may be considered in clinical practice" but that its effectiveness is "unknown/unclear/uncertain or not well-established".[This quote needs a citation]

Research on unspecified or multiple types of meditation

Brain activity

The medial prefrontal and posterior cingulate cortices have been found to be relatively deactivated during meditation (experienced meditators using concentration, lovingkindness and choiceless awareness meditation). In addition experienced meditators were found to have stronger coupling between the posterior cingulate, dorsal anterior cingulate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices both when meditating and when not meditating.[103]

It was also observed that an eight-week MBSR course induced changes in gray matter concentrations.[104] Exploratory whole brain analyses identified significant increases in gray matter concentration in the PCC, TPJ, and the cerebellum. These results suggest that participation in MBSR is associated with changes in gray matter concentration in brain regions involved in learning and memory processes, emotion regulation, self-referential processing, and perspective taking.

Perception

Studies have shown that meditation has both short-term and long-term effects on various perceptual faculties. In 1984 a study showed that meditators have a significantly lower detection threshold for light stimuli of short duration.[105] In 2000 a study of the perception of visual illusions by zen masters, novice meditators, and non-meditators showed statistically significant effects found for the Poggendorff Illusion but not for the Müller-Lyer Illusion. The zen masters experienced a statistically significant reduction in initial illusion (measured as error in millimeters) and a lower decrement in illusion for subsequent trials.[106] Tloczynski has described the theory of mechanism behind the changes in perception that accompany mindfulness meditation thus: "A person who meditates consequently perceives objects more as directly experienced stimuli and less as concepts… With the removal or minimization of cognitive stimuli and generally increasing awareness, meditation can therefore influence both the quality (accuracy) and quantity (detection) of perception."[106] Brown also points to this as a possible explanation of the phenomenon: "[the higher rate of detection of single light flashes] involves quieting some of the higher mental processes which normally obstruct the perception of subtle events."[This quote needs a citation] In other words, the practice may temporarily or permanently alter some of the top-down processing involved in filtering subtle events usually deemed noise by the perceptual filters.[citation needed]

Relaxation response

Herbert Benson, founder of the Mind-Body Medical Institute, which is affiliated with Harvard University and several Boston hospitals, reports that meditation induces a host of biochemical and physical changes in the body collectively referred to as the "relaxation response".[107] The relaxation response includes changes in metabolism, heart rate, respiration, blood pressure and brain chemistry. Benson and his team have also done clinical studies at Buddhist monasteries in the Himalayan Mountains.[108] Benson wrote The Relaxation Response to document the benefits of meditation, which in 1975 were not yet widely known.[109]

Calming effects

According to a March 2006 article in Psychological Bulletin, EEG activity begins to slow as a result of the practice of meditation.[110] The human nervous system is composed of a parasympathetic system, which works to regulate heart rate, breathing and other involuntary motor functions, and a sympathetic system, which arouses the body, preparing it for vigorous activity. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has written, "It is thought that some types of meditation might work by reducing activity in the sympathetic nervous system and increasing activity in the parasympathetic nervous system,"[This quote needs a citation] or equivalently, that meditation produces a reduction in arousal and increase in relaxation.[citation needed]

Work stress

A study of GPs attending a meditation workshop found subsequent falls in their Kessler Psychological Distress Scale - 10 (K10) readings.[111]

Flow

Mindfulness meditation, mindfulness of the breath, and related techniques, are intended to train attention for the sake of provoking insight. A wider, more flexible attention span makes it easier to be aware of a situation, easier to be objective in emotionally or morally difficult situations, and easier to achieve a state of responsive, creative awareness or "flow".[112]

Slowing Ageing Process

Some researches were conducted to understand the malleable determinants of cellular aging, which is critical to understanding human longevity. The researchers concluded saying "We have reviewed data linking stress arousal and oxidative stress to telomere shortness. Meditative practices appear to improve the endocrine balance toward positive arousal (high DHEA, lower cortisol) and decrease oxidative stress. Thus, meditation practices may promote mitotic cell longevity both through decreasing stress hormones and oxidative stress and increasing hormones that may protect the telomere."[113][114][115]

Potential adverse effects and limits of meditation

The following is an official statement from the US government-run National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health:

"Meditation is considered to be safe for healthy people. There have been rare reports that meditation could cause or worsen symptoms in people who have certain psychiatric problems, but this question has not been fully researched. People with physical limitations may not be able to participate in certain meditative practices involving physical movement. Individuals with existing mental or physical health conditions should speak with their health care providers prior to starting a meditative practice and make their meditation instructor aware of their condition."[116]

Adverse effects have been reported,[117][118] and may, in some cases, be the result of "improper use of meditation".[119] The NIH advises prospective meditators to "ask about the training and experience of the meditation instructor… [they] are considering."[116]

As with any practice, meditation may also be used to avoid facing ongoing problems or emerging crises in the meditator's life. In such situations, it may instead be helpful to apply mindful attitudes acquired in meditation while actively engaging with current problems.[120][121] According to the NIH, meditation should not be used as a replacement for conventional health care or as a reason to postpone seeing a doctor.[116]

Weaknesses in historic meditation research

In June, 2007 the United States National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) published an independent, peer-reviewed, meta-analysis of the state of meditation research, conducted by researchers at the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center. The report reviewed 813 studies involving five broad categories of meditation: mantra meditation, mindfulness meditation, yoga, T'ai chi, and Qigong, and included all studies on adults through September 2005, with a particular focus on research pertaining to hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and substance abuse.

The report concluded, "Scientific research on meditation practices does not appear to have a common theoretical perspective and is characterized by poor methodological quality. Firm conclusions on the effects of meditation practices in healthcare cannot be drawn based on the available evidence. Future research on meditation practices must be more rigorous in the design and execution of studies and in the analysis and reporting of results." (p. 6) It noted that there is no theoretical explanation of health effects from meditation common to all meditation techniques.[1]

A version of this report subsequently published in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine stated that "Most clinical trials on meditation practices are generally characterized by poor methodological quality with significant threats to validity in every major quality domain assessed". This was the conclusion despite a statistically significant increase in quality of all reviewed meditation research, in general, over time between 1956 and 2005. Of the 400 clinical studies, 10% were found to be good quality. A call was made for rigorous study of meditation.[3] These authors also noted that this finding is not unique to the area of meditation research and that the quality of reporting is a frequent problem in other areas of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) research and related therapy research domains.

Of more than 3,000 scientific studies that were found in a comprehensive search of 17 relevant databases, only about 4% had randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which are designed to exclude the placebo effect.[1]

A 2013 statement from the American Heart Association evaluated the evidence for the effectiveness of TM as a treatment for hypertension as "unknown/unclear/uncertain or not well-established", and stated: "Because of many negative studies or mixed results and a paucity of available trials... other meditation techniques are not recommended in clinical practice to lower BP at this time."[122]

See also

- Brain activity and meditation

- Buddhism and psychology

- Buddhist meditation

- Meditation

- Mindfulness (psychology)

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d e f Ospina, Maria B.; Bond, Kenneth; Karkhaneh, Mohammad; Tjosvold, Lisa; Vandermeer, Ben; Liang, Yuanyuan; Bialy, Liza; Hooton, Nicola; Buscemi, Nina; Dryden, Donna M.; Klassen, Terry P. (June 2007). "Meditation practices for health: state of the research" (PDF). Evidence Report/technology Assessment (155): 1–263. PMID 17764203.

- ^ Lutz, Antoine; Dunne, John D.; Davidson, Richard J. (2007). "Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness: An Introduction". In Zelazo, Philip David; Moscovitch, Morris; Thompson, Evan (eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 499–552. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511816789.020. ISBN 978-0-511-81678-9.

- ^ a b Ospina MB, Bond K, Karkhaneh M, et al. (December 2008). "Clinical trials of meditation practices in health care: characteristics and quality". J Altern Complement Med. 14 (10): 1199–213. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0307. PMID 19123875.

- ^ a b c Tang YY, Posner MI (January 2013). "Special issue on mindfulness neuroscience". Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience. 8 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1093/scan/nss104.

- ^ Sequeira S (January 2014). "Foreword to advances in meditation research: Neuroscience and clinical applications". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1307: v–vi. doi:10.1111/nyas.12305. PMID 24571183.

- ^ a b Posner MI, Tang YY, Lynch G (2014). "Mechanisms of white matter change induced by meditation training". Frontiers in Psychology. 5 (1220): 297–302. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01220.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Holzel BK, Lazar SW, et al. (November 2011). "How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 6 (6): 537–559. doi:10.1177/1745691611419671. PMID 26168376.

- ^ a b Gotink RA, Chu P, Busschbach JJ, et al. (April 2015). "Standardised Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Healthcare: An Overview of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of RCTs". PLoS ONE. 10 (4): e0124344. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124344. PMC 4400080. PMID 25881019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Goyal, M; Singh, S; Sibinga, E. M.; Gould, N. F.; Rowland-Seymour, A; Sharma, R; Berger, Z; Sleicher, D; Maron, D. D.; Shihab, H. M.; Ranasinghe, P. D.; Linn, S; Saha, S; Bass, E. B.; Haythornthwaite, J. A. (2014). "Meditation Programs for Psychological Stress and Well-being: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (3): 357–68. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. PMID 24395196. (Full text PDF, 439 pp, 12MB)

- ^ a b Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Oliver A, Pettman D (April 2014). "Mindfulness-Based Interventions for People Diagnosed with a Current Episode of an Anxiety or Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials". PLoS ONE. 9 (4): e96110. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096110. PMC 3999148. PMID 24763812.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Khoury B, Sharma M, Rush SE, Fournier C (June 2015). "Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis". J Psychosom Res. 78 (6): 519–528. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009. PMID 25818837.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jain FA, Walsh RN, Eisendrath SJ, et al. (2014). "Critical Analysis of the Efficacy of Meditation Therapies for Acute and Subacute Phase Treatment of Depressive Disorders: A systematic Review". Psychosomatics. 56 (2): 297–302. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2014.10.007.

- ^ Simkin DR, Black NB (July 2014). "Meditation and mindfulness in clinical practice". Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 23 (3): 487–534. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2014.03.002. PMID 24975623.

- ^ Zoogman S, Goldberg SB, Hoyt WT (January 2014). "Mindfulness Interventions with Youth: A Meta-Analysis". Mindfulness. 59 (4): 297–302. doi:10.1093/sw/swu030.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sharma M, Rush SE (July 2014). "Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a stress management intervention for healthy individuals: a systematic review". J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 19 (4): 271–86. doi:10.1177/2156587214543143. PMID 25053754.

- ^ a b Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, et al. (April 2010). "The effect of mindfulness based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review". J Cons Clin Psych. 78 (2): 169–183. doi:10.1037/a0018555.

- ^ Chiesa A (April 2014). "Are mindfulness-based interventions effective for substance use disorders? A systematic review of the evidence". Subst Use Misuse. 49 (5): 492–512. doi:10.3109/10826084.2013.770027. PMID 23461667.

- ^ a b Garland EL (January 2014). "Mindfulness training targets neurocognitive mechanisms of addiction at the attention-appraisal-emotion interface". Front Psychiatry. 4 (173). doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00173.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Black DS (April 2014). "Mindfulness-based interventions: an antidote to suffering in the context of substance use, misuse, and addiction". Subst Use Misuse. 49 (5): 487–91. doi:10.3109/10826084.2014.860749. PMID 24611846.

- ^ Huang HP, He M, Wang HY, Zhou M (June 2015). "A meta-analysis of the benefits of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on psychological function among breast cancer (BC) survivors". J Psychosom Res. 78 (6): 519–528. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009. PMID 25818837.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Godfrey KM, Gallo LC, Afari N (April 2015). "Mindfulness-based interventions for binge eating: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Behav Med. 38 (2): 348–62. doi:10.1007/s10865-014-9610-5. PMID 25417199.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Olson KL, Emery CF (January 2015). "Mindfulness and weight loss: a systematic review". Psychosom Med. 77 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000127. PMID 25490697.

- ^ Shonin E, Van Gordon W, Griffiths MD (February 2014). "Do mindfulness-based therapies have a role in the treatment of psychosis?". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 48 (2): 124–127. doi:10.1177/0004867413512688. PMID 24220133.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chadwick P (May 2014). "Mindfulness for psychosis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 204 (5): 333–334. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.136044.

- ^ Khoury B, Lecomte T, Gaudiano BA, et al. (October 2013). "Mindfulness interventions for psychosis: a meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Research. 150 (1): 176–84. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.055. PMID 23954146.

- ^ a b Querstret D, Cropley M. (2013). "Assessing treatments used to reduce rumination and/or worry: A systematic review". Clinical Psychology Review. 33 (8): 996–1009. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.004. PMID 24036088.

- ^ Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K (April 2015). "How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies". Clin Psychol Rev. 37: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006. PMID 25689576.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Santarnecchi E, D'Arista S, Egiziano E, et al. (October 2014). "Interaction between Neuroanatomical and Psychological Changes after Mindfulness-Based Training". PLoS ONE. 9 (10): e108359. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j8359S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108359. PMC 4203679. PMID 25330321.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Crescentini, C; Capurso, V (2015). "Mindfulness meditation and explicit and implicit indicators of personality and self-concept changes". Front Psychol. 6: 44. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00044. PMC 4310269. PMID 25688222.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Crescentini, Cristiano; Matiz, Alessio; Fabbro, Franco (2015). "Improving Personality/Character Traits in Individuals with Alcohol Dependence: The Influence of Mindfulness-Oriented Meditation". Journal of Addictive Diseases. 34 (1): 75–87. doi:10.1080/10550887.2014.991657. PMID 25585050.

- ^ "Mindfulness Research Guide". Archived from the original on 3 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rapgay, Lobsang; Bystrisky, Alexander (2009). "Classical Mindfulness". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1172 (1): 148–62. Bibcode:2009NYASA1172..148R. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04405.x. PMID 19735247.

- ^ "Research Spotlight: Mindfulness Meditation Is Associated With Structural Changes in the Brain". NCCIH. 30 January 2011.

- ^ Zeidan, F.; Grant, J.A.; Brown, C.A.; McHaffie, J.G.; Coghill, R.C. (June 2012). "Mindfulness meditation-related pain relief: Evidence for unique brain mechanisms in the regulation of pain". Neuroscience Letters. 520 (2): 165–173. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.082.

- ^ Jensen, Mark P.; Day, Melissa A.; Miró, Jordi (18 February 2014). "Neuromodulatory treatments for chronic pain: efficacy and mechanisms". Nature Reviews Neurology. 10 (3): 167–178. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.12.

- ^ Malinowski, Peter (2013). "Neural mechanisms of attentional control in mindfulness meditation". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 7. doi:10.3389/fnins.2013.00008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Evans KC; et al. (March 2010). "Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala". Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 5 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1093/scan/nsp034. PMC 2840837. PMID 19776221.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hölzel, B. K.; Carmody, J; Vangel, M; Congleton, C; Yerramsetti, S. M.; Gard, T; Lazar, S. W. (2011). "Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density". Psychiatry Res. 191 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006. PMC 3004979. PMID 21071182.

- ^ Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness‐based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical psychology: Science and practice, 10(2), 144-156.

- ^ a b Lutz A., Slagter H. A., Dunne J. D., Davidson R. J. (2008). "Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 12 (4): 163–169. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005. PMC 2693206. PMID 18329323.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Moore A., Malinowski P. (2009). "Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility". Consciousness and Cognition. 18 (1): 176–186. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2008.12.008. PMID 19181542.

- ^ Kashdan T. B., Rottenberg J. (2010). "Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect ofhealth". Clinical Psychology Review. 30 (7): 865–878. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001. PMC 2998793. PMID 21151705.

- ^ a b c Malinowski, P. (2013). Neural mechanisms of attentional control in mindfulness meditation. Frontiers in neuroscience, 7.

- ^ Mason M. F., Norton M. I., Van Horn J. D., Wegner D. M., Grafton S. T., Macrae C. N. (2007). "Wandering minds: the default network and stimulus-independent thought". Science. 315 (5810): 393–395. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..393M. doi:10.1126/science.1131295. PMC 1821121. PMID 17234951.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Buckner R.L., Andrews-Hanna J.R., Schacter D.L. (2008). "The brain's default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1124: 1–38. Bibcode:2008NYASA1124....1B. doi:10.1196/annals.1440.011. PMID 18400922.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Seeley W. W., Menon V., Schatzberg A. F., Keller J., Glover G. H., Kenna H., Greicius M. D. (2007). "Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (9): 2349–2356. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.5587-06.2007. PMC 2680293. PMID 17329432.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fan J., McCandliss B. D., Fossella J., Flombaum J. I., Posner M. I. (2005). "The activation of attentional networks". NeuroImage. 26 (2): 471–479. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.004. PMID 15907304.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Posner M. I., Rothbart M. K. (2007). "Research on attention networks as a model for the integration of psychological science". Annu. Rev. Psychol. 58: 1–23. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085516. PMID 17029565.

- ^ Schmertz S. K., Anderson P. L., Robins D. L. (2009). "The relation between self-report mindfulness and performance on tasks of sustained attention". Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 31 (1): 60–66. doi:10.1007/s10862-008-9086-0.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Electroencephalography

- ^ Slagter H. A., Lutz A., Greischar L. L., Francis A. D., Nieuwenhuis S., Davis J. M., Davidson R. J. (2007). "Mental training affects distribution of limited brain resources". PLOS Biology. 5 (6): e138. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050138. PMC 1865565. PMID 17488185.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Jha A. P., Krompinger J., Baime M. J. (2007). "Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention". Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 7 (2): 109–119. doi:10.3758/cabn.7.2.109.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Fan J., McCandliss B.D., Sommer T., Raz A., Posner M.I. (2002). "Testing the efficiency and independence of attentionalnetworks". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 14 (3): 340–347. doi:10.1162/089892902317361886. PMID 11970796.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van , den Hurk P. A., Giommi F., Gielen S. C., Speckens A. E., Barendregt H. P. (2010). "Greater efficiency in attentional processing related to mindfulness meditation". The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 63 (6): 1168–1180. doi:10.1080/17470210903249365. PMID 20509209.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Tang Y.Y., Ma Y., Wang J., Fan Y., Feng S., Lu Q., Posner M.I. (2007). "Short-term meditation training improves attentionand self-regulation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (43): 17152–17156. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707678104. PMC 2040428. PMID 17940025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chan D., Woollacott M. (2007). "Effects of level of meditation experience on attentional focus: Is the efficiency of executive ororientation networks improved?". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 13 (6): 651–657. doi:10.1089/acm.2007.7022.

- ^ Anderson N.D., Lau M.A., Segal Z.V., Bishop S.R. (2007). "Mindfulness-based stress reduction and attentional control". Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 14 (6): 449–463. doi:10.1002/cpp.544.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hölzel B. K., Lazar S. W., Gard T., Schuman-Olivier Z., Vago D. R., Ott U. (2011). "How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 6 (6): 537–559. doi:10.1177/1745691611419671. PMID 26168376.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moore, A., Gruber, T., Derose, J., & Malinowski, P. (2012). Regular, brief mindfulness meditation practice improves electrophysiological markers of attentional control. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 6.

- ^ a b c d Chambers R., Lo B. C. Y., Allen N. B. (2008). "The impact of intensive mindfulness training on attentional control, cognitive style, and affect". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 32 (3): 303–322. doi:10.1007/s10608-007-9119-0.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hayes A. M., Feldman G. (2004). "Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy". Clinical Psychology: science and practice. 11 (3): 255–262. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph080.

- ^ Treynor W., Gonzalez R., Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2003). "Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 27 (3): 247–259. doi:10.1023/a:1023910315561.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kumar S., Feldman G., Hayes A. (2008). "Changes in mindfulness and emotion regulation in an exposure-based cognitive therapy for depression". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 32 (6): 734–744. doi:10.1007/s10608-008-9190-1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramel W., Goldin P. R., Carmona P. E., McQuaid J. R. (2004). "The effects of mindfulness meditation on cognitive processes and affect in patients with past depression". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 28 (4): 433–455.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baer R. A. (2003). "Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review". Clinical psychology: Science and practice. 10 (2): 125–143. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg015.

- ^ Kabat-Zinn J., Massion A. O., Kristeller J., Peterson L. G., Fletcher K. E., Pbert L.; et al. (1992). "Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders". American Journal of Psychiatry. 149 (7): 936–944. doi:10.1176/ajp.149.7.936.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., ... & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical psychology: Science and practice, 11(3), 230-241.

- ^ a b c Desbordes, G., Gard, T., Hoge, E. A., Hölzel, B. K., Kerr, C., Lazar, S. W., ... & Vago, D. R. (2014). Moving beyond mindfulness: defining equanimity as an outcome measure in meditation and contemplative research. Mindfulness, 1-17.

- ^ Teasdale J. D. (1999). "Metacognition, mindfulness and the modification of mood disorders". Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 6 (2): 146–155. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0879(199905)6:2<146::aid-cpp195>3.0.co;2-e.

- ^ Masuda A., Hayes S. C., Sackett C. F., Twohig M. P. (2004). "Cognitive defusion and self-relevant negative thoughts: Examining the impact of a ninety-year-old technique". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 42 (4): 477–485. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2003.10.008. PMID 14998740.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hayes, S. C. (2003). Mindfulness: method and process. Clinical Psychology: Science andPractice, 10(2), 161−165.

- ^ Ochsner K.N., Gross J.J. (2005). "The cognitive control of emotion". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 9 (5): 242–249. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. PMID 15866151.

- ^ a b Goldin P. R., Gross J. J. (2010). "Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder". Emotion. 10 (1): 83–91. doi:10.1037/a0018441. PMC 4203918. PMID 20141305.

- ^ Cuthbert B. N., Schupp H. T., Bradley M. M., Birbaumer N., Lang P. J. (2000). "Brain potentials in affective picture processing: covariation with autonomic arousal and affective report". Biological Psychology. 52 (2): 95–111. doi:10.1016/s0301-0511(99)00044-7. PMID 10699350.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schupp H.T., Cuthbert B.N., Bradley M.M., Cacioppo J.T., Ito T., Lang P.J. (2000). "Affective picture processing: The late positive potential is modulated by motivational relevance". Psychophysiology. 37 (2): 257–61. doi:10.1111/1469-8986.3720257. PMID 10731776.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schupp H.T., Jungho , Weike A.I., Hamm A.O. (2003). "Attention and emotion: AnERP analysis of facilitated emotional stimulus processing". NeuroReport. 14 (8): 1107–10. doi:10.1097/00001756-200306110-00002. PMID 12821791.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brown, K. W., Goodman, R. J., & Inzlicht, M. (2012). Dispositional mindfulness and the attenuation of neural responses to emotional stimuli. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, nss004.

- ^ Ortner C. N., Kilner S. J., Zelazo P. D. (2007). "Mindfulness meditation and reduced emotional interference on a cognitive task". Motivation and Emotion. 31 (4): 271–283. doi:10.1007/s11031-007-9076-7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goldin P., Ziv M., Jazaieri H., Gross J.J. (2013). "MBSR vs. aerobic exercise in socialanxiety: fMRI of emotion regulation of negative self-beliefs". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 8 (1): 65–72. doi:10.1093/scan/nss054. PMC 3541489. PMID 22586252.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Farb N.A.S., Segal Z.V., Mayberg H., Bean J., McKeon D., Fatima Z., Anderson A.K. (2007). "Attending to the present:Mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of selfreference". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2 (4): 313–322. doi:10.1093/scan/nsm030. PMC 2566754. PMID 18985137.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Quirk G. J., Beer J. S. (2006). "Prefrontal involvement in the regulation of emotion: Convergence of rat and human studies". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 16 (6): 723–727. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2006.07.004. PMID 17084617.

- ^ Chiesa A., Calati R., Serretti A. (2011). "Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings". Clinical Psychology Review. 31 (3): 449–464. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003. PMID 21183265.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kurth, F; Luders, E; Wu, B; Black, D. S. (2014). "Brain Gray Matter Changes Associated with Mindfulness Meditation in Older Adults: An Exploratory Pilot Study using Voxel-based Morphometry". Neuro. 1 (1): 23–26. doi:10.17140/NOJ-1-106. PMC 4306280. PMID 25632405.

- ^ Tang, Yi-Yuan; Posner, Michael I. (2013). "Tools of the trade: theory and method in mindfulness neuroscience". Oxford Journals: Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 8 (1): 118–120. doi:10.1093/scan/nss112. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ Karunamuni ND (May 2015). "The Five-Aggregate Model of the Mind". SAGE Open. 5 (2). doi:10.1177/2158244015583860.

- ^ Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Wasserman RH; et al. (November 2005). "Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness". NeuroReport. 16 (17): 1893–7. doi:10.1097/01.wnr.0000186598.66243.19. PMC 1361002. PMID 16272874.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aftanas, LI; Golocheikine, SA (September 2001). "Human anterior and frontal midline theta and lower alpha reflect emotionally positive state and internalized attention: high-resolution EEG investigation of meditation". Neuroscience Letters. 310 (1): 57–60. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02094-8. PMID 11524157.

- ^ Aftanas, Ljubomir; Golosheykin, Semen (June 2005). "Impact of regular meditation practice on EEG activity at rest and during evoked negative emotions". The International Journal of Neuroscience. 115 (6): 893–909. doi:10.1080/00207450590897969. PMID 16019582.

- ^ Aftanas, LI; Golocheikine, SA (September 2002). "Non-linear dynamic complexity of the human EEG during meditation". Neuroscience Letters. 330 (2): 143–6. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00745-0. PMID 12231432.

- ^ Manocha, Ramesh; Black, Deborah; Spiro, David; Ryan, Jake; Stough, Con (March 2010). "Changing Definitions of Meditation – Is there a Physiological Corollary? Skin temperature changes of a mental silence orientated form of meditation compared to rest" (PDF). Journal of the International Society of Life Sciences. 28 (1): 23–31.

- ^ http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2012/350674/

- ^ Venkatesh S, Raju TR, Shivani Y, Tompkins G, Meti BL (April 1997). "A study of structure of phenomenology of consciousness in meditative and non-meditative states". Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 41 (2): 149–53. PMID 9142560.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Beauregard, Mario; Paquette, Vincent (September 2006). "Neural correlates of a mystical experience in Carmelite nuns". Neuroscience Letters. 405 (3): 186–90. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.060. PMID 16872743.

- ^ Mystical Brain[non-primary source needed]

- ^ "Meditation boosts part of brain where ADD, addictions reside". Ars Technica. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Tang, Yi-Yuan; Lu, Qilin; Geng, Xiujuan; Stein, Elliot A.; Yang, Yihong; Posner, Michael I. (August 2010). "Short-term meditation induces white matter changes in the anterior cingulate". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (35): 15649–52. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10715649T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011043107. JSTOR 27862304. PMC 2932577. PMID 20713717.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Lyn Freeman, Mosby’s Complementary & Alternative Medicine: A Research-Based Approach, Mosby Elsevier, 2009, p. 163

- ^ a b Krisanaprakornkit, Thawatchai; Sriraj, Wimonrat; Piyavhatkul, Nawanant; Laopaiboon, Malinee (2006). "Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004998. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004998.pub2. PMID 16437509.

- ^ Ernst E (2011). Bonow RO; et al. (eds.). Chapter 51: Complementary and Alternative Approaches to Management of Patients with Heart Disease (9th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-2708-1.

A systematic review of six RCTs of transcendental meditation failed to generate convincing evidence that meditation is an effective treatment for hypertension

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) (References the same 2004 systematic review by Canter and Ernst on TM and hypertension that is separately referenced in this article) - ^ Canter, Peter H; Ernst, Edzard (November 2004). "Insufficient evidence to conclude whether or not Transcendental Meditation decreases blood pressure: results of a systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Journal of Hypertension. 22 (11): 2049–54. doi:10.1097/00004872-200411000-00002. PMID 15480084.

- ^ a b Krisanaprakornkit, Thawatchai; Ngamjarus, Chetta; Witoonchart, Chartree; Piyavhatkul, Nawanant (2010). "Meditation therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD006507. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006507.pub2. PMID 20556767.

- ^ Canter, Peter H.; Ernst, Edzard (November 2003). "The cumulative effects of Transcendental Meditation on cognitive function — a systematic review of randomised controlled trials". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 115 (21–22): 758–66. doi:10.1007/BF03040500. PMID 14743579.

- ^ Brewer, Judson A.; Worhunsky, Patrick D.; Gray, Jeremy R.; Tang, Yi-Yuan; Weber, Jochen; Kober, Hedy (December 2011). "Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (50): 20254–9. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10820254B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112029108. JSTOR 23060108. PMC 3250176. PMID 22114193.

- ^ Hölzel, B. K.; Carmody, J; Vangel, M; Congleton, C; Yerramsetti, S. M.; Gard, T; Lazar, S. W. (2011). "Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density". Psychiatry Res. 191 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006. PMC 3004979. PMID 21071182.

- ^ Brown, Daniel; Forte, Michael; Dysart, Michael (June 1984). "Differences in visual sensitivity among mindfulness meditators and non-meditators". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 58 (3): 727–33. doi:10.2466/pms.1984.58.3.727. PMID 6382144.

- ^ a b Tloczynski, Joseph; Santucci, Aimee; Astor-Stetson, Eileen (December 2000). "Perception of visual illusions by novice and longer-term meditators". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 91 (3 Pt 1): 1021–6. doi:10.2466/pms.2000.91.3.1021. PMID 11153836.

- ^ Benson, Herbert (December 1997). "The relaxation response: therapeutic effect". Science. 278 (5344): 1693–7. Bibcode:1997Sci...278.1693B. doi:10.1126/science.278.5344.1693b. PMID 9411784.

- ^ Cromie, William J. (18 April 2002). "Meditation changes temperatures: Mind controls body in extreme experiments". Harvard University Gazette. Archived from the original on 24 May 2007.

- ^ Benson, Herbert (2001). The Relaxation Response. HarperCollins. pp. 61–3. ISBN 0-380-81595-8.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Cahn, B. Rael; Polich, John (March 2006). "Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies". Psychological Bulletin. 132 (2): 180–211. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.180. PMID 16536641.

- ^ Manoch, Ramesh; Gordon, Amy; Black, Deborah; Malhi, Gin; Seidler, Raymond (June 2009). "Using meditation for less stress and better wellbeing - A seminar for GPs". Australian Family Physician. 38 (6): 454–8. PMID 19530378.

- ^ Marr, Arthur J. (April 2001). "Commentary: In the Zone: A Biobehavioral Theory of the Flow Experience". Athletic Insight. 3 (1).

- ^ Epel E, Daubenmier J, Moskowitz JT, Folkman S, Blackburn E (August 2009). "Can meditation slow rate of cellular aging? Cognitive stress, mindfulness, and telomeres". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1172: 34–53. Bibcode:2009NYASA1172...34E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04414.x. PMC 3057175. PMID 19735238.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ a b c "Meditation: An Introduction". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. June 2010.

- ^ Perez-De-Albeniz, Alberto; Holmes, Jeremy (2000). "Meditation: Concepts, effects and uses in therapy". International Journal of Psychotherapy. 5 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1080/13569080050020263.

- ^ Rocha, Tomas (25 June 2014). "The Dark Knight of the Soul". The Atlantic.

- ^ Turner, Robert P.; Lukoff, David; Barnhouse, Ruth Tiffany; Lu, Francis G. (July 1995). "Religious or spiritual problem. A culturally sensitive diagnostic category in the DSM-IV". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 183 (7): 435–44. doi:10.1097/00005053-199507000-00003. PMID 7623015.

- ^ Hayes, 1999, chap. 3[full citation needed]

- ^ Metzner, 2005[page needed][full citation needed]

- ^ Brook, Robert D.; Appel, Lawrence J.; Rubenfire, Melvyn; Ogedegbe, Gbenga; Bisognano, John D.; Elliott, William J.; Fuchs, Flavio D.; Hughes, Joel W.; Lackland, Daniel T.; Staffileno, Beth A.; Townsend, Raymond R.; Rajagopalan, Sanjay (June 2013). "Beyond medications and diet: alternative approaches to lowering blood pressure: a scientific statement from the american heart association". Hypertension. 61 (6): 1360–83. doi:10.1161/HYP.0b013e318293645f. PMID 23608661.

External links

- Marchant, Jo (23 April 2011). "How meditation might ward off the effects of ageing". The Observer.