Ricky Nelson

Rick Nelson | |

|---|---|

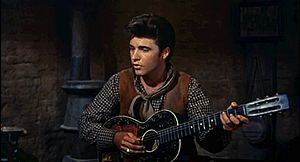

Nelson in concert in Lawton, Oklahoma | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Eric Hilliard Nelson |

| Born | May 8, 1940 Teaneck, New Jersey, US |

| Died | December 31, 1985 (aged 45) De Kalb, Texas, US |

| Genres | Rockabilly, Rock 'n' roll, Pop, Folk, Country |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, musician, singer-songwriter |

| Years active | 1949–1985 |

| Labels | Imperial, Decca/MCA, Epic |

| Website | rickynelson |

Eric Hilliard Nelson (May 8, 1940 – December 31, 1985) – known as Ricky Nelson, later also as Rick Nelson – was an American actor, musician and singer-songwriter. He starred alongside his family in the television series, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (1952–66), as well as co-starring alongside John Wayne and Dean Martin in Howard Hawks's western feature film, Rio Bravo (1959). He placed 53 songs on the Billboard Hot 100 between 1957 and 1973 including "Poor Little Fool" which holds the distinction of being the first #1 song on Billboard magazine's then-newly created Hot 100 chart. He recorded 19 additional Top 10 hits and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on January 21, 1987.[1][2] In 1996, he was ranked #49 on TV Guide's 50 Greatest TV Stars of All Time.[3]

Nelson began his entertainment career in 1949 playing himself in the radio sitcom series, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. In 1952, he appeared in his first feature film, Here Come the Nelsons. In 1957, he recorded his first single, debuted as a singer on the television version of the sitcom, and released the #1 album entitled Ricky. In 1958, Nelson released his first #1 single, "Poor Little Fool", and in 1959 received a Golden Globe nomination for "Most Promising Male Newcomer" after starring in Rio Bravo. A few films followed, and when the television series was cancelled in 1966, Nelson made occasional appearances as a guest star on various television programs.

Nelson and Sharon Kristin Harmon were married on April 20, 1963, and divorced in December 1982. They had four children: Tracy Kristine, twin sons Gunnar Eric and Matthew Gray, and Sam Hilliard.

Early life

Ricky Nelson was born on May 8, 1940, in Teaneck, New Jersey.[4][5][6] He was the second son of big band leader Ozzie Nelson, who was of half Swedish descent, and his wife, big band vocalist Harriet Hilliard Nelson (née Peggy Louise Snyder). Harriett remained in Englewood, New Jersey, with her newborn and her older son David while Ozzie toured the nation with the Nelson orchestra.[7] The Nelsons bought a two-story colonial house in Tenafly, New Jersey,[7][8] and, six months after the purchase, moved with son David to Hollywood, where Ozzie and Harriet were slated to appear in the 1941–42 season of Red Skelton's The Raleigh Cigarette Hour; Ricky remained in Tenafly in the care of his paternal grandmother.[9] In November 1941, the Nelsons bought what would become their permanent home: a green and white, two-story, Cape Cod colonial home at 1822 Camino Palmero in Los Angeles.[10][11] Ricky joined his parents and brother in Los Angeles in 1942.[10]

Ricky was a small and insecure child who suffered from severe asthma. At night, his sleep was eased with a vaporizer emitting tincture of evergreen.[12] He was described by Red Skelton's producer John Guedel as "an odd little kid," likable, shy, introspective, mysterious, and inscrutable.[13] When Skelton was drafted in 1944, Guedel crafted the radio sitcom The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet for Ricky's parents.[13][14] The show debuted on Sunday, October 8, 1944, to favorable reviews.[15][16] Ozzie eventually became head writer for the show and based episodes on the fraternal exploits and enmity of his sons.[17] The Nelson boys were first played in the radio series by professional child actors until twelve-year-old Dave and eight-year-old Ricky joined the show on February 20, 1949, in the episode "Invitation to Dinner."[18][19]

In 1952, the Nelsons tested the waters for a television series with the theatrically released film Here Come the Nelsons. The film was a hit, and Ozzie was convinced the family could make the transition from radio's airwaves to television's small screen. On October 3, 1952, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet made its television debut and was broadcast in first run until September 3, 1966, to become one of the longest-running sitcoms in television history.

Education

Nelson attended Gardner Street Public School,[20] Bancroft Junior High,[21] and, between 1954 and 1958, Hollywood High School, from which he graduated with a B average.[22][23] He played football at Hollywood High[22][23] and represented the school in interscholastic tennis matches.[24] Twenty-five years later, Nelson told the Los Angeles Weekly he hated school because it "smelled of pencils" and he was forced to rise early in the morning to attend.[22]

At Hollywood High, Nelson was blackballed by the Elksters, a fraternity of a dozen conservative sports-loving teens who thought him too wild. Many of the Elksters were family friends and spent weekends at the Nelson home playing basketball or relaxing around the pool. In retaliation, he joined the Rooks, a greaser car club of sideburned high school teens clad in leather jackets and motorcycle boots. He tattooed his hands, wrist, and shoulder with India ink and a sewing needle, slicked his hair with oil, and accompanied the Rooks on nocturnal forays along Hollywood Boulevard randomly harassing and beating up passersby. Nelson was jailed twice in connection with incidents perpetrated by the Rooks, and escaped punishment after sucker-punching a police officer only through the intervention of his father. Nelson’s parents were alarmed. Their son’s juvenile delinquency did little to enhance the All-American image of Ozzie and Harriet and they quickly put an end to Ricky’s involvement with the Rooks by banishing one of the most influential of the club’s members from Ricky’s life and their home.

One of Ricky's seldom-publicized traits was his "fierce loyalty" to boyhood friends whom he regarded as trusted confidants. When young friend Bill Aken was in a crippling auto accident in New York City and confined to a hospital bed for months, Ricky would often phone Billy's mother, asking about his progress and writing short notes and letters to Billy to cheer him up. They became lifelong friends, and Aken recorded the only family-authorized tribute record ("Gentle Friend") for the fan club after Rick's death.

Ozzie Nelson was a Rutgers alumnus and keen on college education,[25] but eighteen-year-old Ricky was already in the 93 percent income-tax bracket and saw no reason to attend.[23] At age thirteen, Ricky was making over $100,000 per annum, and at sixteen he had a personal fortune of $500,000.[26] Nelson's wealth was astutely managed by his parents, who channeled his earnings into trust funds. Although his parents permitted him a $50 allowance at the age of eighteen, Rick was often strapped for cash and one evening collected and redeemed empty pop bottles to gain entrance to a movie theater for himself and a date.[27] [28]

Music career

Debut

Nelson played clarinet and drums in his tweens and early teens, learned the rudimentary guitar chords, and vocally imitated his favorite Sun Records rockabilly artists in the bathroom at home or in the showers at the Los Angeles Tennis Club.[29][30][31] He was strongly influenced by the music of Carl Perkins and once said he tried to emulate the sound and the tone of the guitar break in Perkins's March 1956 Top Ten hit "Blue Suede Shoes."[30][31]

At age sixteen, he wanted to impress a girl friend who was an Elvis Presley fan and, although he had no record contract at the time, told her that he, too, was going to make a record.[29][32][33][34] With his father's help, he secured a one-record deal with Verve Records, an important jazz label looking for a young and popular personality who could sing or be taught to sing.[33][34][35][36] On March 26, 1957, he recorded the Fats Domino standard "I'm Walkin'" and "A Teenager's Romance" (released in late April 1957 as his first single),[37] and "You're My One and Only Love".[36][38]

Before the single was released, he made his television rock-and-roll debut on April 10, 1957 singing and playing the drums to "I'm Walkin'" in the Ozzie and Harriet episode "Ricky, the Drummer".[39][40] About the same time, he made an unpaid public appearance, singing "Blue Moon of Kentucky" with the Four Preps at a Hamilton High School lunch hour assembly[37] in Los Angeles and was greeted by hordes of screaming teens who had seen the television episode.[41][42]

"I'm Walkin'" reached #4 on Billboard's Best Sellers in Stores chart, and its flip side, "A Teenager's Romance", hit #2.[33][42] When the television series went on summer break in 1957, Nelson made his first road trip and played four state and county fairs in Ohio and Wisconsin with the Four Preps, who opened and closed for him.[43]

First album, band, and #1 single

In early summer 1957, Ozzie Nelson pulled his son from Verve after disputes about royalties and signed him to a lucrative five-year deal with Imperial Records that gave him approval over song selection, sleeve artwork, and other production details.[44][45] Ricky's first Imperial single, "Be-Bop Baby", generated 750,000 advance orders, sold over one million copies, and reached #3 on the charts. Nelson's first album, Ricky, was released in October 1957 and hit #1 before the end of the year.[46] Following these successes, Nelson was given a more prominent role on the Ozzie and Harriet show and ended every two or three episodes with a musical number.[47]

Nelson grew increasingly dissatisfied performing with older jazz session musicians, who were openly contemptuous of rock and roll. After his Ohio and Minnesota tours in the summer of 1957, he decided to form his own band with members closer to his age.[48] Eighteen-year-old electric guitarist James Burton was the first signed. Bassist James Kirkland, drummer Richie Frost, and pianist Gene Garf completed the band.[49] Their first recording together was "Believe What You Say".

In 1958, Nelson recorded 17-year-old Sharon Sheeley's "Poor Little Fool" for his second album, Ricky Nelson, released in June 1958.[50][51] Radio airplay brought the tune notice, and Imperial suggested releasing a single, but Nelson opposed the idea, believing a single would diminish EP sales. When a single was released nonetheless, he exercised his contractual right to approve any artwork and vetoed a picture sleeve.[50][52] On August 4, 1958, "Poor Little Fool" became the #1 single on Billboard's newly instituted Hot 100 singles chart[53][54] and sold over two million copies.[50]

Nelson stated

Anyone who knocks rock 'n' roll either doesn't understand it, or is prejudiced against it, or is just plain square. – NME – November 1958[55]

During 1958 and 1959, Nelson placed twelve hits on the charts in comparison with Presley's eleven. During these two years, Presley had only recorded music for King Creole in January and February 1958 before his induction into the U.S. Armed Forces, and a brief recording session consisting of five songs while on Military Leave four months later. In the summer of 1958, Nelson conducted his first full-scale tour, averaging $5,000 nightly. By 1960, the Ricky Nelson International Fan Club had 9,000 chapters around the world.[56]

Perhaps the most embarrassing moment in my career was when six girls tried to fling themselves under my car, and shouted to me to run over them. That sort of thing can be very frightening! – NME – May 1960[57]

Nelson was the first teen idol to utilize television to promote hit records. Ozzie Nelson even had the idea to edit footage together to create some of the first music videos. This creative editing can be seen in videos Ozzie produced for "Travelin' Man." Nelson appeared on the Sullivan show in 1967, but his career by that time was in limbo. He also appeared on other television shows (usually in acting roles). In 1973, he had an acting role in an episode of The Streets of San Francisco. He starred in the episode "A Hand For Sonny Blue" from the 1977 series Quinn Martin's Tales of the Unexpected (known in the United Kingdom as Twist in the Tale).[58] In 1979, he guest-hosted on Saturday Night Live, spoofing his television sitcom image by appearing in a Twilight Zone sendup in which, always trying to go "home," he finds himself among the characters from other 1950s/early 1960s-era sitcoms, Leave It to Beaver, Father Knows Best, Make Room for Daddy, and I Love Lucy.

Nelson knew and loved music and was a skilled performer even before he became a teen idol, largely because of his parents' musical background. Nelson worked with many musicians of repute, including James Burton, Joe Osborn, and Allen "Puddler" Harris, all natives of Louisiana, and Joe Maphis, The Jordanaires, Scotty Moore, and Johnny and Dorsey Burnette.

Nelson's music was very well recorded with a clear, punchy sound—thanks in part to engineer Bunny Robyn and producer Jimmy Haskell. Details are here.

From 1957 to 1962, Nelson had 30 Top-40 hits, more than any other artist except Presley (who had 53) and Pat Boone (38). Many of Nelson's early records were double hits with both the A and B sides hitting the Billboard charts.

While Nelson preferred rockabilly and uptempo rock songs like "Believe What You Say" (Hot 100 #4), "I Got a Feeling" (#10), "My Bucket's Got a Hole in It" (#12), "Hello Mary Lou" (#9), "It's Late" (#9), "Stood Up" (#2), "Waitin' in School" (#18), "Be-Bop Baby" (#3), and "Just a Little Too Much" (#9), his smooth, calm voice made him a natural to sing ballads. He had major success with "Travelin' Man" (#1), "A Teenager's Romance" (#2), "Poor Little Fool" (#1), "Young World" (#5), "Lonesome Town" (#7), "Never Be Anyone Else But You" (#6), "Sweeter Than You" (#9), "It's Up to You" (#6), and "Teen Age Idol" (#5), which clearly could have been about Nelson himself.

Film actor

In addition to his recording career, Nelson appeared in movies, including the Howard Hawks western classic Rio Bravo with John Wayne, Dean Martin, and Walter Brennan (1959), plus The Wackiest Ship in the Army (1960) with Jack Lemmon and Love and Kisses (1965) with Jack Kelly.

Name change

On May 8, 1961 (his 21st birthday), he officially modified his recording name from "Ricky Nelson" to "Rick Nelson". His childhood nickname proved hard to shake, especially among the generation who had watched him grow up on "Ozzie and Harriet". Even in the 1980s, when Nelson realized his dream of meeting Carl Perkins, Perkins noted that he and "Ricky" were the last of the "rockabilly breed."

In 1963, Nelson signed a 20-year contract with Decca Records. After some early successes with the label, most notably 1964's "For You" (#6), Nelson's chart career came to a dramatic halt in the wake of Beatlemania and The British Invasion.

In the mid 1960s, Nelson began to move towards country music, becoming a pioneer in the country-rock genre. He was one of the early influences of the so-called "California Sound" (which would include singers like Jackson Browne and Linda Ronstadt and bands like the Eagles). Yet Nelson himself did not reach the Top 40 again until 1970, when he recorded Bob Dylan's "She Belongs to Me" with the Stone Canyon Band, featuring Randy Meisner, who in 1971 became a founding member of the Eagles, and former Buckaroo steel guitarist Tom Brumley.

"Garden Party"

In 1972, Nelson reached the Top 40 one last time with "Garden Party", a song he wrote in disgust after a Richard Nader Oldies Concert at Madison Square Garden where the audience booed him, because, he felt, he was playing new songs instead of just his old hits. When he performed The Rolling Stones' "Honky Tonk Women", he was booed off the stage. He was watching the rest of the performance on a TV monitor backstage and Richard Nader finally convinced Nelson to return to the stage and play his "oldies". He returned to the stage and played his "oldies" and the audience responded with applause, according to Deborah Nader, President of Richard Nader Entertainment. He wanted to record an album featuring original material, but the single was released before the album because Nelson had not completed the entire Garden Party album yet. "Garden Party" reached #6 on the Billboard Hot 100 and #1 on the Billboard Adult Contemporary chart and was certified as a gold single. The second single released from the album was "Palace Guard" which peaked at #65.

Nelson was with MCA at the time, and his comeback was short-lived. Nelson's band soon resigned, and MCA wanted Nelson to have a producer on his next album. His band moved to Aspen and changed their name to "Canyon". Nelson soon put together a new Stone Canyon Band and began to tour for the Garden Party album. Nelson still played nightclubs and bars, but he soon advanced to higher-paying venues because of the success of Garden Party. In 1974 MCA was at odds as to what to do with the former teen idol. Albums like Windfall failed to have an impact. Nelson became an attraction at theme parks like Knott's Berry Farm and Disneyland. He also started appearing in minor roles on television shows.

Nelson tried to score another hit but did not have any luck with songs like "Rock and Roll Lady." With seven years to go on his contract, MCA dropped him from the label.

Personal life

In 1957, when Nelson was 17, he met and fell in love with Marianne Gaba, who played the role of Ricky's girlfriend in three episodes of Ozzie and Harriet.[59][60] Nelson and Gaba were too young to entertain a serious relationship, although according to Gaba "we used to neck for hours."[61][62] The next year, Nelson fell in love with 15-year-old Lorrie Collins, a country singer appearing on a weekly telecast called Town Hall Party.[63][64] The two wrote Nelson's first composition, the song "My Gal," and she introduced him to Johnny Cash and Tex Ritter. Collins appeared in an Ozzie and Harriet episode as Ricky's girlfriend and sang "Just Because" with him in the musical finale.[65] They went steady and discussed marriage, but their parents discouraged the idea.[65][66][67][68]

Kris Harmon

At Christmas 1961, Nelson began dating Sharon Kristin "Kris" Harmon (born June 25, 1945), the daughter of football legend Tom Harmon and actress Elyse Knox (née Elsie Kornbrath) and the older sister of Kelly and Mark Harmon.[69][70] The Nelsons and the Harmons had long been friends, and a union between their children held great appeal.[71] Rick and Kris had much in common: quiet dispositions, Hollywood upbringings, and high-powered, domineering fathers.[72]

They married on April 20, 1963. Kris was pregnant,[73] and Rick later described the union as a "shotgun wedding."[74] Nelson, a nonpracticing Protestant, received instruction in Catholicism at the insistence of the bride's parents[74][75] and signed a pledge to have any children of the union raised in the Catholic faith.[73] Kris Nelson joined the television show as a regular cast member in 1963.[68][76] They had four children: actress Tracy Kristine Nelson, twin sons Gunnar Eric Nelson and Matthew Gray Nelson who formed the band Nelson, and Sam Hilliard Nelson.

By 1975, following the birth of their last child, the marriage had deteriorated and a very public, controversial divorce involving both families was covered in the press for several years. In October 1977, Kris filed for divorce and asked for alimony, custody of their four children, and a portion of community property. The couple temporarily resolved their differences, but Kris retained her attorney to pursue a permanent break.[77] [78] Kris wanted Rick to give up music, spend more time at home, and focus on acting, but the family enjoyed a recklessly expensive lifestyle, and Kris's extravagant spending left Rick no choice but to tour relentlessly.[79] The impasse over Rick's career created unpleasantness at home. Kris became an alcoholic and left the children in the care of household help.[80] After years of legal proceedings, they were divorced in December 1982. The divorce was financially devastating for Nelson, with attorneys and accountants taking over $1 million.[81] Years of legal wrangling followed.[82][83]

Georgeann Crewe

On May 16, 1980, Nelson met Georgeann Crewe at the Playboy Resort in Great Gorge, New Jersey.[90][91] Crewe later claimed she felt "an attachment, an immediate attraction" to Nelson.[90][91] Crewe unsuccessfully attempted to contact Nelson several times to let him know that she was pregnant, and on February 14, 1981, she gave birth to Nelson's son, Eric Jude Crewe.[90] In 1985, a blood test confirmed Nelson was the father,[90] but Nelson was not interested in Crewe or their son. He declined to meet with them to the point that he avoided playing concerts in Atlantic City. Although Nelson agreed to provide $400 a month in child support, he did not provide for the child in his will.[92]

Helen Blair

In 1980, Nelson met Helen Blair, a part-time model and exotic animal trainer, in Las Vegas.[84] Within months of their meeting, she became his road companion, and in 1982 she moved in with him. She was the only woman he dated after his divorce.[84][85]

Blair acted as personal assistant to Nelson, organizing his day and acting as a liaison for his fan club,[84] but Nelson's mother, brother, business manager, and manager disapproved of her presence in his life.[86] He contemplated marrying her but eventually declined.[87] Blair died with Nelson in the airplane fire. Her name was never mentioned at Nelson's funeral.[88] Blair's parents wanted their daughter buried next to Nelson at Forest Lawn Cemetery, but Harriet Nelson dismissed the idea.[89] The Blairs refused to bury Helen's remains and filed a $2 million wrongful death suit against Nelson's estate.[88] They received a small settlement. Nelson did not provide for Blair in his will.[90]

Comeback Tour

In 1985, Rick began a "Comeback tour" with Fats Domino. He put the "y" back on his name and called himself "Ricky." He sang the songs that he was famous for and released a greatest hits album, "Ricky Nelson: All My Best." His comeback was cut short when his plane crashed later that year on New Year's Eve - as part of the tour circuit.

Death

Nelson dreaded flying but refused to travel by bus. In May 1985, he decided he needed a private plane and leased a luxurious, fourteen-seat, 1944 Douglas DC-3 that had once belonged to the DuPont family and later to Jerry Lee Lewis. The plane had been plagued by a history of mechanical problems.[91] In one incident, the band was forced to push the plane off the runway after an engine blew, and in another incident, a malfunctioning magneto prevented Nelson from participating in the first Farm Aid concert in Champaign, Illinois.

On December 26, 1985, Nelson and the band left for a three-stop tour of the Southern United States. Following shows in Orlando, Florida, and Guntersville, Alabama, Nelson and band members took off from Guntersville for a New Year's Eve extravaganza in Dallas, Texas.[92] The plane crash-landed northeast of Dallas in De Kalb, Texas, less than two miles from a landing strip, at approximately 5:14 pm. CST on December 31, 1985, hitting trees as it came to earth. Seven of the nine occupants were killed: Nelson and his companion, Helen Blair; bass guitarist Patrick Woodward, drummer Rick Intveld, keyboardist Andy Chapin, guitarist Bobby Neal, and road manager/soundman Donald Clark Russell. Pilots Ken Ferguson and Brad Rank escaped via cockpit windows, though Ferguson was severely burned.

Nelson's remains were misdirected in transit from Texas to California, delaying the funeral for several days. On January 6, 1986, 250 mourners entered the Church of the Hills for funeral services while 700 fans gathered outside. Attendees included 'Colonel' Tom Parker, Connie Stevens, Angie Dickinson, and dozens of actors, writers, and musicians. Nelson was privately buried days later in the Forest Lawn, Hollywood Hills Cemetery in Los Angeles.[93] Kris Nelson threatened to sue the Nelson clan for her former husband's life insurance money and tried to wrest control of his estate from David Nelson, its administrator. Her bid was rejected by a Los Angeles Superior Court judge. Nelson bequeathed his entire estate to his children and did not provide for Kris Nelson. Only days after the funeral, rumors and newspaper reports suggested cocaine freebasing was one of several possible causes for the plane crash. Those allegations were refuted by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB).[94]

Reports vary as to whether or not the plane was on fire before it crashed. According to witnesses, the plane appeared to be on fire before it crash-landed. However Jim Burnett, then-Chairman of the NTSB, said that even though the plane was filled with smoke, it landed and came to a stop before it was swallowed by flames.[95] The NTSB conducted a year-long investigation and finally concluded that, while a definite cause was still unknown, the crash was probably due to a fire that was caused by the plane's cabin heater "acting up".[96][97]

When questioned by the NTSB, pilots Brad Rank and Ken Ferguson had different accounts of key events. According to co-pilot Ferguson, the cabin heater was acting up after the plane took off. Ferguson continued that Rank kept going to the back of the plane to see if he could get the heater to function correctly and that Rank told Ferguson several times to turn the heater back on. "One of the times, I refused to turn it on," said Ferguson. He continued, "I was getting more nervous. I didn't think we should be messing with that heater en-route." After the plane crashed, Ferguson and Rank climbed out the cockpit windows, suffering from extensive burns. They shouted to the passenger cabin, but there was no response. Ferguson and Rank backed away from the plane, fearing explosion. Ferguson stated that Rank told him, "Don't tell anyone about the heater, don't tell anyone about the heater."[97]

Pilot Rank, however, told a different story: Rank said that he was checking on the passengers when he noticed smoke in the middle of the cabin, where Rick Nelson and Helen Blair were sitting. Even though he never mentioned a problematic heater, Rank stated that he went to the rear of the plane to check the heater, saw no smoke, and found the heater was cool to the touch. After activating an automatic fire extinguisher and opening the cabin's fresh air inlets, Rank said that he returned to the cockpit where Ferguson was already asking traffic controllers for directions to the nearest airfield.[97]

Rank was criticized by the NTSB for not following the inflight fire checklist, opening the fresh air vents instead of leaving them closed, not instructing the passengers to use supplemental oxygen, and not attempting to fight the fire with the handheld fire extinguisher that was in the cockpit. The board said that while these steps might not have prevented the crash, "they would have enhanced the potential for survival of the passengers."[97] The words of the NTSB seem to echo that of firefighter, Lewis Glover, who was one of the first on the scene. Glover stated, "All the bodies are there at the front of the plane. Apparently, they were trying to escape the fire."[98]

An examination indicated that a fire had originated on the right side of the aft cabin area at or near the floorline. Some reports said the passengers were killed when the aircraft struck obstacles during the forced landing. The ignition and fuel sources of the fire could not be determined.[99] According to another report, the pilot indicated that the crew repeatedly tried to turn on the gasoline cabin heater shortly before the fire occurred, but that it failed to respond. After the fire, the access panel to the heater compartment was found unlatched. The theory is supported by records that showed that DC-3s in general, and this aircraft in particular, had a history of problems with the cabin heaters.

Tributes, honors, recognition

- Nelson was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987, and to the Rockabilly Hall of Fame. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1515 Vine Street.

- Along with the recording's other participants, Nelson earned the 1987 Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album for "Interviews from the Class of '55 Recording Sessions."

- In 1994, a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs, California, Walk of Stars was dedicated to him.[100]

- In 2004, Rolling Stone ranked Nelson #91 on their list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[101]

- At the 20th anniversary of Nelson's death, PBS televised Ricky Nelson Sings, a documentary featuring interviews with his children, as well as James Burton and Kris Kristofferson. On December 27, 2005, EMI Music released an album entitled Ricky Nelson's Greatest Hits which peaked at #56 on the Billboard 200 album chart.

- Bob Dylan wrote about Nelson's influence on his music in his 2004 memoir, "Chronicles, Vol. 1".

- Nelson's estate (The Rick Nelson Company, LLC) owns ancillary rights to the Ozzie and Harriet television series, and, in 2007, Shout! Factory released official editions of the show on DVD. Also in 2007, Nelson was inducted into the Hit Parade Hall of Fame.

- The John Frusciante song "Ricky" was inspired by Ricky Nelson.

- Hall of Fame baseball player Rickey Henderson was named Rickey Nelson Henley after Ricky Nelson.[102]

- For the 25th anniversary of Nelson's death, Rock and Roll Hall-of-Famer, James Burton, Nelson's original guitarist for nearly ten years, spoke about his friendship and experiences with the singer in an extensive series of interviews for Examiner.com. The first installment is entitled "Remembering Rick Nelson: An Interview With His Friend, Guitarist James Burton."

- Included in the Scandinavian-American hall of fame in 2014

Discography

References

- Bashe, Philip (1992). Teenage Idol, Travelin' Man: The Complete Biography of Rick Nelson. New York: Hyperion Books. ISBN 1-56282-969-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brackett, Nathan (Ed.); Hoard, Christian (Deputy Ed.) (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bronson, Fred (2003). Billboard's Hottest Hot 100 Hits. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN 0-8230-7738-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dennis, Jeffrey P. (2006). Queering Teen Culture: All-American Boys and Same-Sex Desire in Film and Television. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press, Inc. ISBN 1-56023-349-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holdship, Bill (2005). Ricky Nelson Greatest Hits. Hollywood, CA: Capitol Records.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pohlen, Jerome (2006). Oddball Texas: A Guide to Some Really Strange Places. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 1-55652-583-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Selvin, Joel (1990). Ricky Nelson: Idol for a Generation. Contemporary Books. ISBN 0-8092-4187-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Notes

- ^ Whitburn

- ^ Bashe 284

- ^ "Special Collectors' Issue: 50 Greatest TV Stars of All Time". TV Guide (December 14–20). 1996.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Bashe 2,16–7

- ^ Selvin 25

- ^ Nelson was called "Ricky" from birth (Bashe 16).

- ^ a b Bashe 17

- ^ Selvin 26

- ^ Bashe 18

- ^ a b Bashe 19

- ^ Selvin 28

- ^ Bashe 19–20

- ^ a b Bashe 20

- ^ Selvin 29

- ^ Bashe 21

- ^ Selvin 30

- ^ Bashe 22

- ^ Bashe 24–5

- ^ Dennis 15

- ^ Bashe 23

- ^ Selvin 47

- ^ a b c Selvin 53

- ^ a b c Bashe 52

- ^ Selvin 55

- ^ Selvin 15

- ^ Bashe 53

- ^ Bashe 54

- ^ Bashe 55

- ^ a b Bashe 1992, p. 66.

- ^ a b Selvin 1990, p. 62.

- ^ a b Holdship 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Selvin 1990, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Bronson 154

- ^ a b Holdship 2005, p. 1.

- ^ Bashe 1992, p. 69.

- ^ a b Selvin 1990, p. 64.

- ^ a b Ricky Nelson interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- ^ Bashe 1992, p. 71.

- ^ Bashe 1992, p. 72.

- ^ Selvin 1990, p. 66.

- ^ Bashe 1992, p. 75.

- ^ a b Selvin 1990, p. 68.

- ^ Selvin 1990, p. 70.

- ^ Bashe 78–9

- ^ Selvin 73–4

- ^ Selvin 76

- ^ Bashe 80

- ^ Bashe 81

- ^ Bashe 83

- ^ a b c Bashe 90

- ^ Selvin 89

- ^ Selvin 89–90

- ^ Bashe 91

- ^ Selvin 90

- ^ Tobler, John (1992). NME Rock 'N' Roll Years (1st ed.). Londonet: Reed International Books Ltd. p. 60. CN 5585.

- ^ Bashe 92–3

- ^ Tobler, John (1992). NME Rock 'N' Roll Years (1st ed.). London: Reed International Books Ltd. p. 82. CN 5585.

- ^ Classic Television Archive: Quinn Martin's Tales of the Unexpected (1977)

- ^ Bashe 136

- ^ Selvin 72

- ^ Bashe 137

- ^ Selvin 73

- ^ Bashe 106

- ^ Selvin 81

- ^ a b Selvin 83

- ^ Bashe 138

- ^ Selvin 116

- ^ a b Bashe 145

- ^ Bashe 138,140–1

- ^ Selvin 140

- ^ Bashe 139

- ^ Bashe 140

- ^ a b Selvin 149

- ^ a b Bashe 144

- ^ Selvin 137,149

- ^ Selvin 150

- ^ Selvin 230

- ^ Bashe 205

- ^ Selvin 251

- ^ Bashe 218

- ^ Bashe 221

- ^ Bashe 237

- ^ Selvin 262

- ^ a b c Bashe 242

- ^ Selvin 260

- ^ Bashe 242,244

- ^ Bashe 246

- ^ a b Bashe 273

- ^ Bashe 244

- ^ Bashe 271

- ^ Bashe 259

- ^ Bashe 261–2

- ^ Ricky Nelson at Find a Grave

- ^ "Free-Basing Ruled Out in Nelson Crash". United Press International. May 28, 1987. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Jones, Jack (January 3, 1986). "Probers Look to 2 Survivors for Clues in Crash That Killed Rick Nelson". LA Times. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Baker, Kathryn (July 3, 1986). "Report on Rick Nelson Plane Crash Centers on Cabin Heater". Associated Press. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Pagano, Penny (May 29, 1987). "Probe Discounts Drugs as Cause of Air Crash That Killed Rick Nelson". LA Times. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Beitler, Stu. "De Kalb, TX Rick Nelson Dies in Airplane Crash, Dec 1985". GenDisasters. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "NTSB Report DCA86AA012 File No. 2932". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Palm Springs Walk of Stars by date dedicated

- ^ "The Immortals: The First Fifty". Rolling Stone (946). April 15, 2004. ISSN 0035-791X. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ^ Noble, Marty (July 21, 2007). "Notes: Henderson's rockin' past". MLB.com. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

External links

- Rick/Ricky Nelson's Official Website

- Ricky Nelson at IMDb

- Ricky Nelson at AllMusic

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

- U.S. National Transportation Safety Board Report on plane crash

- Ricky Nelson at Find a Grave

- Rockabilly Hall

- Ricky Nelson interviewed on The Pop Chronicles (recorded November 17, 1967)[1]

- RCS Artist Discography

- 1940 births

- 1985 deaths

- People from Teaneck, New Jersey

- American people of Swedish descent

- Accidental deaths in Texas

- American male child actors

- American male film actors

- American country singers

- American country singer-songwriters

- American pop singers

- American male radio actors

- American male television actors

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills)

- Charly Records artists

- Decca Records artists

- Epic Records artists

- Grammy Award winners

- Imperial Records artists

- Singers from New Jersey

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in the United States

- Country musicians from New Jersey

- 20th-century American male actors

- Teen idols

- 20th-century American singers