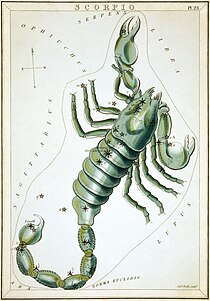

Scorpius

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Sco |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Scorpii |

| Pronunciation | /ˈskɔːrpiəs/, genitive /ˈskɔːrpiaɪ/ |

| Symbolism | the Scorpion |

| Right ascension | 16.8875 |

| Declination | −30.7367 |

| Quadrant | SQ3 |

| Area | 497 sq. deg. (33rd) |

| Main stars | 18 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 47 |

| Stars with planets | 14 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 13 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 3 |

| Brightest star | Antares (α Sco) (0.96m) |

| Messier objects | 4 |

| Meteor showers | Alpha Scorpiids Omega Scorpiids |

| Bordering constellations | Sagittarius Ophiuchus Libra Lupus Norma Ara Corona Australis |

| Visible at latitudes between +40° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of July. | |

Scorpius is one of the constellations of the zodiac. Its name is Latin for scorpion, and its symbol is ![]() (Unicode ♏). It lies between Libra to the west and Sagittarius to the east. It is a large constellation located in the southern hemisphere near the center of the Milky Way.

(Unicode ♏). It lies between Libra to the west and Sagittarius to the east. It is a large constellation located in the southern hemisphere near the center of the Milky Way.

Notable features

Stars

Scorpius contains many bright stars, including Antares (α Sco), "rival of Mars," so named because of its distinct reddish hue; β1 Sco (Graffias or Acrab), a triple star; δ Sco (Dschubba, "the forehead"); θ Sco (Sargas, of unknown origin); ν Sco (Jabbah); ξ Sco (Girtab, "the scorpion"); π Sco (Iclil); σ Sco (Alniyat); and τ Sco (also known as Alniyat, "the arteries").[1][2]

Marking the tip of the scorpion's curved tail are λ Sco (Shaula) and υ Sco (Lesath), whose names both mean "sting." Given their proximity to one another, λ Sco and υ Sco are sometimes referred to as the Cat's Eyes.[3]

The constellation's bright stars form a pattern like a longshoreman's hook. Most of them are massive members of the nearest OB association: Scorpius-Centaurus.[4]

The star δ Sco, after having been a stable 2.3 magnitude star, flared in July 2000 to 1.9 in a matter of weeks. It has since become a variable star fluctuating between 2.0 and 1.6.[5] This means that at its brightest it is the second brightest star in Scorpius.

U Scorpii is the fastest known nova with a period of about 10 years.[6]

ω¹ Scorpii and ω² Scorpii are an optical double, which can be resolved by the unaided eye. They have contrasting blue and yellow colours.

The star once designated γ Sco (despite being well within the boundaries of Libra) is today known as σ Lib. Moreover, the entire constellation of Libra was considered to be claws of Scorpius (Chelae Scorpionis) in Ancient Greek times, with a set of scales held aloft by Astraea (represented by adjacent Virgo) being formed from these western-most stars during later Greek times. The division into Libra was formalised during Roman times.

Deep-sky objects

Due to its location on the Milky Way, this constellation contains many deep-sky objects such as the open clusters Messier 6 (the Butterfly Cluster) and Messier 7 (the Ptolemy Cluster), NGC 6231 (by ζ² Sco), and the globular clusters Messier 4 and Messier 80.

Messier 80 (NGC 6093) is a globular cluster of magnitude 7.3, 33,000 light-years from Earth. It is a compact Shapley class II cluster; the classification indicates that it is highly concentrated and dense at its nucleus. M80 was discovered in 1781 by Charles Messier. It was the site of a rare discovery in 1860 when Arthur von Auwers discovered the nova T Scorpii.[7]

NGC 6302, also called the Bug Nebula, is a bipolar planetary nebula. NGC 6334, also known as the Cat's Paw Nebula, is an emission nebula and star-forming region.

Mythology

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (March 2015) |

In Greek mythology, the myths associated with Scorpio almost invariably also contain a reference to Orion. According to one of these myths it is written that Orion boasted to goddess Artemis and her mother, Leto, that he would kill every animal on the Earth. Although Artemis was known to be a hunter herself she offered protection to all creatures. Artemis and her mother Leto sent a scorpion to deal with Orion. The pair battled and the scorpion killed Orion. However, the contest was apparently a lively one that caught the attention of the king of the gods Zeus, who later raised the scorpion to heaven and afterwards, at the request of Artemis, did the same for Orion to serve as a reminder for mortals to curb their excessive pride. There is also a version that Orion was better than the goddess Artemis but said that Artemis was better than he and so Artemis took a liking to Orion. The god Apollo, Artemis's twin brother, grew angry and sent a scorpion to attack Orion. After Orion was killed, Artemis asked Zeus to put Orion up in the sky. So every winter Orion hunts in the sky, but every summer he flees as the constellation of the scorpion comes.

In another Greek story involving Scorpio without Orion, Phaeton (the mortal male offspring of Helios) went to his father, who had earlier sworn by the River Styx to give Phaeton anything he should ask for. Phaeton wanted to drive his father's Sun Chariot for a day. Although Helios tried to dissuade his son, Phaeton was adamant. However, when the day arrived, Phaeton panicked and lost control of the white horses that drew the chariot. First, the Earth grew chill as Phaeton flew too high and encountered the celestial scorpion, its deadly sting raised to strike. Alarmed, he dipped the chariot too close, causing the vegetation to burn. By accident, Phaeton turned most of Africa into desert and darkened the skin of the Ethiopian nation until it was black. Eventually, Zeus was forced to intervene by striking the runaway chariot and Phaeton with a lightning bolt to put an end to its rampage and Phaeton plunged into the River Eridanos.[8]

Origins

The Babylonians called this constellation MUL.GIR.TAB - the 'Scorpion', the signs can be literally read as 'the (creature with) a burning sting'.

In some old descriptions the constellation of Libra is treated as the Scorpion's claws. Libra was known as the Claws of the Scorpion in Babylonian (zibānītu (compare Arabic zubānā)) and in Greek (χηλαι).[9]

Astrology

The Western astrological sign Scorpio of the tropical zodiac (October 23 – November 21) differs from the astronomical constellation and the Hindu astrological sign of the sidereal zodiac (November 16 – December 16). Astronomically, the sun is in Scorpius for just six days, from November 23 to November 28. Much of the difference is due to the constellation Ophiuchus, which is used by only a few astrologers. Scorpius corresponds to the nakshatras Anuradha, Jyeshtha, and Mula.

Culture

The Javanese people of Indonesia call this constellation Banyakangrem ("the brooded swan")[10] or Kalapa Doyong ("leaning coconut tree")[11] due to the shape similarity.

See also

References

- ^ Mark R. Chartrand III (1983) Skyguide: A Field Guide for Amateur Astronomers, p. 184 (ISBN 0-307-13667-1).

- ^ Constellations: A Guide to the Night Sky, http://www.constellation-guide.com/constellation-list/scorpius-constellation/

- ^ Fred Schaaf (Macmillan 1988) 40 Nights to Knowing the Sky: A Night-by-Night Sky-Watching Primer, p. 79 (ISBN 9780805046687).

- ^ Preibisch, T.; Mamajek, E. (2009). "The Nearest OB Association: Scorpius-Centaurus (Sco OB2)". Handbook of Star-Forming Regions. 2: 0. arXiv:0809.0407. Bibcode:2008hsf2.book..235P.

- ^ Delta Scorpii Still Showing Off

- ^ AAVSO: Variable Star of the Season: U Scorpii

- ^ Levy 2005, pp. 166–167.

- ^ according to Scorpio - The Legend and Myth

- ^ Babylonian Star-lore by Gavin White, Solaria Pubs, 2008 page 175

- ^ Daldjoeni, N (1984). "Pranatamangsa, the javanese agricultural calendar – Its bioclimatological and sociocultural function in developing rural life". The Environmentalist. 4: 15–18. doi:10.1007/BF01907286.

- ^ Jejak Langkah Astronomi di Indonesia

- Levy, David H. (2005). Deep Sky Objects. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-59102-361-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion (2007). Stars and Planets Guide, Collins, London. ISBN 978-0-00-725120-9. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

External links

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Scorpius

- Star Tales – Scorpius

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (over 300 medieval and early modern images of Scorpius)