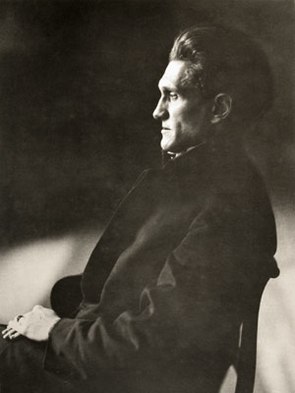

Stefan George

Stefan George | |

|---|---|

Stefan George (1910) | |

| Born | 12 June 1868 Büdesheim, Grand Duchy of Hesse, German Empire |

| Died | 4 December 1933 Minusio, Ticino, Switzerland |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | German |

| Nationality | German |

| Notable awards | Goethe Prize (1927) |

| Parents | Stephan George Eva Schmitt/George |

Stefan Anton George (German: [ˈʃtɛfan ˈantoːn ɡeˈɔʁɡə]; 12 July 1868 – 4 December 1933) was a German poet, editor, and translator.

Biography

George was born in 1868 in Büdesheim, today part of Bingen in the Grand Duchy of Hesse (now part of the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate). His father, also Stephan George, was an inn keeper and wine merchant.

His schooling was successfully concluded in 1888, after which he spent time in London and in Paris, where he was among the writers and artists who attended the Tuesday soirées held by the poet Stéphane Mallarmé. His early travels also included Vienna, where in 1891 he met, for the first time, Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

He began to publish poetry in the 1890s, while in his twenties. George founded and edited an important literary magazine called Blätter für die Kunst. He was also at the center of an influential literary and academic circle known as the George-Kreis, which included many of the leading young writers of the day, (for example Friedrich Gundolf and Ludwig Klages). In addition to sharing cultural interests, the circle reflected mystical and political themes. George knew and befriended the "Bohemian Countess" of Schwabing, Fanny zu Reventlow, who sometimes satirized the circle for its melodramatic actions and views. George and his writings were identified with the Conservative Revolutionary movement. He was a homosexual, yet exhorted his young friends to lead a celibate life like his own.[1][2]

In 1914 at the start of the war he foretold a sad end for Germany, and between then and 1916 wrote the pessimistic poem Der Krieg (The War). The outcome of the war saw the realization of his worst fears.

In 1933 after the Nazi takeover Joseph Goebbels offered him the presidency of a new Academy for the arts, which he refused. He also stayed away from celebrations prepared for his 65th birthday. Instead he travelled to Switzerland, where he died near Locarno. After his death, his body was interred before a delegation from the National Socialist government could attend the ceremony.[3]

Work

George's poetry is characterized by an aristocratic and remote ethos; his verse is formal in style, lyrical in tone, and often arcane in language, being influenced by Greek classical forms, in revolt against the realist trend in German literature at the time. Believing that the purpose of poetry was distance from the world—he was a strong advocate of art for art's sake —George's writing had many ties with the French Symbolist movement and he was in contact with many of its representatives, including Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine.

George was an important bridge between the 19th century and German modernism, even though he was a harsh critic of the then modern era. He experimented with various poetic metres, punctuation, obscure allusions and typography. George's "evident homosexuality"[4] is reflected in works such as Algabal and the love poetry he devoted to a gifted adolescent of his acquaintance named Maximilian Kronberger,[5] whom he called "Maximin", and whom he identified as a manifestation of the divine. The relevance of George's sexuality to his poetic work has been discussed by contemporary critics, such as Thomas Karlauf and Marita Keilson-Lauritz.[6]

Algabal is one of George's best remembered collections of poetry, if also one of his strangest; the title is a reference to the effete Roman emperor Elagabalus. George was also an important translator; he translated Dante, Shakespeare and Baudelaire into German.

George was awarded the Goethe Prize in 1927.[7]

Das neue Reich

George's late and seminal work, Das neue Reich ("The New Empire"), was published in 1928. He dedicated the work, including the Geheimes Deutschland ("Secret Germany") written in 1922, to Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, who, in 1944, took part in the 20 July plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler.[8] It outlines a new form of society ruled by hierarchical spiritual aristocracy. George rejected any attempts to use it for mundane political purposes, especially National Socialism.

Influence

George was thought of by his contemporaries as a prophet and a priest, while he thought of himself as a messiah of a new kingdom that would be led by intellectual or artistic elites, bonded by their faithfulness to a strong leader. In his memoirs, Albert Speer claims to have seen George in the early 1920s and that his elder brother, Hermann, was a member of his inner circle: George "radiated dignity and pride and a kind of priestliness... there was something magnetic about him."

His poetry emphasized self-sacrifice, heroism and power, and he thus gained popularity in National Socialist circles. The group of writers and admirers that formed around him were known as the Georgekreis. Although many National Socialists claimed George as an important influence, George himself was aloof from such associations and did not get involved in politics. Shortly after the Nazi seizure of power, George left Germany for Switzerland where he died the same year.

Many of the leading members of the German Resistance to the Nazis were drawn from among his followers, notably the Stauffenberg brothers who were introduced to George by the poet and classical scholar Albrecht von Blumenthal. Although some members of the circle were explicitly anti-semitic (for example, Klages), it also included Jewish writers such as Gundolf, the historian Ernst Kantorowicz, and the Zionist Karl Wolfskehl. George was fond enough of his Jewish disciples, but he expressed reservations about their ever becoming a majority in the Circle.

Perhaps the most eminent poet who collaborated with George, but who ultimately refused membership in the Circle, was Hugo von Hofmannsthal, one of Austria's outstanding literary modernists. Later in life, Hofmannsthal wrote that no one had influenced him more deeply than George. Those closest to the "Master," as George had his disciples call him, included several members of the 20 July plot to assassinate Hitler, among them Claus von Stauffenberg himself. Stauffenberg frequently quoted George's poem Der Widerchrist (The Anti-Christ) to his fellow members of the 20 July plot.[9]

Outside the Circle, George's poetry was a major influence on the music of the Second Viennese School of composers, particularly during their Expressionist period. Arnold Schoenberg set George's poetry in such works as "Ich darf nicht dankend", Op. 14/1 (1907), String Quartet No. 2, Op. 10 (1908), and The Book of the Hanging Gardens, Op. 15 (1909), while his student Anton Webern made use of George's verse in his early choral work Entflieht auf leichten Kähnen,, Op. 2, as well as in two sets of songs, Opp. 3 and 4 of 1909, and in several posthumously published vocal works from the same period.

In Rainer Werner Fassbinder's 1976 film Satansbraten the protagonist Walter Kranz attempts to model his life on that of George.

Bibliography

Each year links to its corresponding "[year] in poetry" article (except for Tage und Taten, a prose work):

- 1890: Hymnen ("Hymns"), 18 poems written reflecting Symbolism; dedicated to Carl August Klein; limited, private edition[10]

- 1891: Pilgerfahrten ("Pilgrimages") limited, private edition[10]

- 1892: Algabal (1892); illustrated by Melchior Lechter; limited, private edition[10]

- 1897: Das Jahr der Seele ("The Year of the Soul")[10]

- 1899: Teppich des Lebens ("The Tapestry of Life")[10]

- 1900: Hymnen, Pilgerfahrten, and Algabal, a one-volume edition published in Berlin by Georg Bondi which first made George's work available to the public at large[10]

- 1901: Die Fibel ("Primer"), poems written from 1886-1889[10]

- 1903: Tage und Taten ("Days and Works"; cf. Hesiod's Works and Days)[10]

- 1907: Der siebente Ring ("The Seventh Ring")[10]

- 1913: Der Stern des Bundes ("The Star of the Covenant")[10]

- 1917: Der Krieg ("The War")[10]

- 1928: Das neue Reich ("The Kingdom Come")[10]

References

- ^ Boehringer, Robert. Mein Bild von Stefan George. München, Düsseldorf: Helmut Küpper vormals Georg Bondi Verlag, 1967. pp. 126-127

- ^ Thomas Karlauf: Stefan George. Die Entdeckung des Charisma. Blessing, München 2007. ISBN 978-3-89667-151-6

- ^ Robert E. Norton, Secret Germany: Stefan George and his Circle (Cornell University Press, 2002)

- ^ Robert E. Norton, Secret Germany: Stefan George and his Circle (Cornell University Press, 2002) page 354

- ^ Palmer, Craig B. (2002), "George, Stefan", glbtq.com, retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ See for example, Marita Keilson-Lauritz, "Ubergeschlechtliche Liebe: Stefan George's Concept of Love" (Rieckmann, ed A Companion to the Works of Stefan George (Camden House, 2005)

- ^ "Stefan George, 65, German poet, dies". New York Times. 4 December 1933. p. 23.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Herbert Ammon: Vom Geist Georges zur Tat Stauffenbergs - Manfred Riedels Rettung des Reiches, in: Iablis 2007 at www.iablis.de

- ^ Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death: The Story of the German Resistance, Metropolitan Books, 1994. Page 216.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Stefan George, Poems, Trans. & Ed. Carol North Valhope and Ernst Morwitz. (New York: Pantheon, 1946).

Further reading

- Breuer, Stefan (1996). Ästhetischer Fundamentalismus: Stefan George und der deutsche Antimodernismus. Darmstadt: Primus.

- Capetanakis, D., 'Stefan George', in Demetrios Capetanakis A Greek Poet In England (1947), p. 72-89

- Frank, Lore & Sabine Ribbeck (2000). Stefan-George-Bibliographie 1976-1997. Mit Nachträgen bis 1976. Auf der Grundlage der Bestände des Stefan-George-Archivs in der Württembergischen Landesbibliothek. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Goldsmith, Ulrich (1951). Stefan George and the theatre. New York: The Modern Language Association (PLMA Publications LXVI:2).

- Goldsmith, Ulrich (1959). Stefan George: A study of his early work. Boulder: University of Colorado Press (University of Colorado Studies Series in Language and Literature 7).

- Goldsmith, Ulrich (1970). Stefan George. New York: Columbia University Press (Essays on Modern Writers).

- Goldsmith, Ulrich (1974). Shakespeare and Stefan George: The sonnets. Berne: Franke.

- Kluncker, Karlhans (1985). "Das geheime Deutschland": Über Stefan George und seinen Kreis. Bonn: Bouvier (Abhandlungen zur Kunst-, Musik- und Literaturwissenschaft 355).

- Norton, Robert E. (2002). Secret Germany: Stefan George and his Circle. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Schmitz, Victor (1978). Stefan George und Rainer Maria Rilke: Gestaltung und Verinnerlichung. Berne: Wild.

- Rieckmann, Jens (ed.) (2005). A Companion to the Works of Stefan George. Camden House.

- Lacchin, Giancarlo (2006). Stefan George e l'antichità. Lineamenti di una filosofia dell'arte. Lugano: University Words.

- Schefold, Bertram. (2011). Politische Ökonomie als Geisteswissenschaft. Edgar Salin und andere Ökonomen um Stefan George, in Studien zur Entwicklung der ökonomischen Theorie, XXVI. Edited by Harald Hagemann, Duncker & Humblot

External links

- Concise overview

- The Writings of Stefan George Online (In German)

- Stefan George letters to Ernst Morwitz, 1905-1956. Manuscripts and Archives, New York Public Library.

- Works by or about Stefan George at the Internet Archive

- Works by Stefan George at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Some poems in both German and English

- 1868 births

- 1933 deaths

- People from Bingen am Rhein

- People from Rhenish Hesse

- Conservative Revolutionary movement

- German expatriates in Switzerland

- German-language poets

- German poets

- German translators

- German World War I poets

- LGBT writers from Germany

- French–German translators

- Translators from Italian

- Translators of William Shakespeare

- Translators of Dante Alighieri

- Translators to German

- Gay writers

- LGBT poets

- German male poets

- German male dramatists and playwrights

- German nationalists