Stem cell: Difference between revisions

Tag: references removed |

|||

| Line 455: | Line 455: | ||

The outcome of this legal challenge is particularly relevant to the Geron Corp. as it can only license patents that are upheld.<ref name="Kintisch">Kintisch, Eli (July 18, 2006) [http://news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2006/07/18-02.html "Groups Target Stem Cell Patents."] ''ScienceNOW Daily News''. Retrieved August 15, 2006.</ref> |

The outcome of this legal challenge is particularly relevant to the Geron Corp. as it can only license patents that are upheld.<ref name="Kintisch">Kintisch, Eli (July 18, 2006) [http://news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2006/07/18-02.html "Groups Target Stem Cell Patents."] ''ScienceNOW Daily News''. Retrieved August 15, 2006.</ref> |

||

dicks dicks dicks |

|||

==Key research events== |

==Key research events== |

||

Revision as of 19:22, 6 May 2010

Stem cells are cells found in all multi cellular organisms. They are characterized by the ability to renew themselves through mitotic cell division and differentiate into a diverse range of specialized cell types. Research in the stem cell field grew out of findings by Canadian scientists Ernest A. McCulloch and James E. Till in the 1960s.[1][2] The two broad types of mammalian stem cells are: embryonic stem cells that are isolated from the inner cell mass of blastocysts, and adult stem cells that are found in adult tissues. In a developing embryo, stem cells can differentiate into all of the specialized embryonic tissues. In adult organisms, stem cells and progenitor cells act as a repair system for the body, replenishing specialized cells, but also maintain the normal turnover of regenerative organs, such as blood, skin, or intestinal tissues.

Stem cells can now be grown and transformed into specialized cells with characteristics consistent with cells of various tissues such as muscles or nerves through cell culture. Highly plastic adult stem cells from a variety of sources, including umbilical cord blood and bone marrow, are routinely used in medical therapies. Embryonic cell lines and autologous embryonic stem cells generated through therapeutic cloning have also been proposed as promising candidates for future therapies.[3]

Properties

The classical definition of a stem cell requires that it possess two properties:

- Self-renewal - the ability to go through numerous cycles of cell division while maintaining the undifferentiated state.

- Potency - the capacity to differentiate into specialized cell types. In the strictest sense, this requires stem cells to be either totipotent or pluripotent - to be able to give rise to any mature cell type, although multipotent or unipotent progenitor cells are sometimes referred to as stem cells.

Potency definitions

A: Cell colonies that are not yet differentiated.

B: Nerve cell

Potency specifies the differentiation potential (the potential to differentiate into different cell types) of the stem cell.[4]

- Totipotent (a.k.a omnipotent) stem cells can differentiate into embryonic and extraembryonic cell types. Such cells can construct a complete, viable, organism.[4] These cells are produced from the fusion of an egg and sperm cell. Cells produced by the first few divisions of the fertilized egg are also totipotent.[5]

- Pluripotent stem cells are the descendants of totipotent cells and can differentiate into nearly all cells,[4] i.e. cells derived from any of the three germ layers.[6]

- Multipotent stem cells can differentiate into a number of cells, but only those of a closely related family of cells.[4]

- Oligopotent stem cells can differentiate into only a few cells, such as lymphoid or myeloid stem cells.[4]

- Unipotent cells can produce only one cell type, their own,[4] but have the property of self-renewal which distinguishes them from non-stem cells (e.g. muscle stem cells).

Identification

The practical definition of a stem cell is the functional definition - a cell that has the potential to regenerate tissue over a lifetime. For example, the gold standard test for a bone marrow or hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) is the ability to transplant one cell and save an individual without HSCs. In this case, a stem cell must be able to produce new blood cells and immune cells over a long term, demonstrating potency. It should also be possible to isolate stem cells from the transplanted individual, which can themselves be transplanted into another individual without HSCs, demonstrating that the stem cell was able to self-renew.

Properties of stem cells can be illustrated in vitro, using methods such as clonogenic assays, where single cells are characterized by their ability to differentiate and self-renew.[7][8] As well, stem cells can be isolated based on a distinctive set of cell surface markers. However, in vitro culture conditions can alter the behavior of cells, making it unclear whether the cells will behave in a similar manner in vivo. Considerable debate exists whether some proposed adult cell populations are truly stem cells.

Embryonic

Embryonic stem cell lines (ES cell lines) are cultures of cells derived from the epiblast tissue of the inner cell mass (ICM) of a blastocyst or earlier morula stage embryos.[9] A blastocyst is an early stage embryo—approximately four to five days old in humans and consisting of 50–150 cells. ES cells are pluripotent and give rise during development to all derivatives of the three primary germ layers: ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm. In other words, they can develop into each of the more than 200 cell types of the adult body when given sufficient and necessary stimulation for a specific cell type. They do not contribute to the extra-embryonic membranes or the placenta.

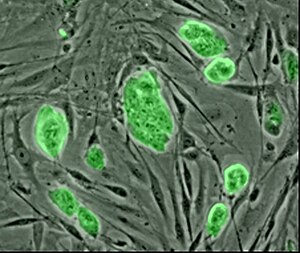

Nearly all research to date has taken place using mouse embryonic stem cells (mES) or human embryonic stem cells (hES). Both have the essential stem cell characteristics, yet they require very different environments in order to maintain an undifferentiated state. Mouse ES cells are grown on a layer of gelatin and require the presence of Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF).[10] Human ES cells are grown on a feeder layer of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and require the presence of basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF or FGF-2).[11] Without optimal culture conditions or genetic manipulation,[12] embryonic stem cells will rapidly differentiate.

A human embryonic stem cell is also defined by the presence of several transcription factors and cell surface proteins. The transcription factors Oct-4, Nanog, and Sox2 form the core regulatory network that ensures the suppression of genes that lead to differentiation and the maintenance of pluripotency.[13] The cell surface antigens most commonly used to identify hES cells are the glycolipids SSEA3 and SSEA4 and the keratan sulfate antigens Tra-1-60 and Tra-1-81. The molecular definition of a stem cell includes many more proteins and continues to be a topic of research.[14]

After nearly ten years of research,[15] there are no approved treatments using embryonic stem cells. The first human trial was approved by the US Food & Drug Administration in January 2009.[16] ES cells, being pluripotent cells, require specific signals for correct differentiation - if injected directly into another body, ES cells will differentiate into many different types of cells, causing a teratoma. Differentiating ES cells into usable cells while avoiding transplant rejection are just a few of the hurdles that embryonic stem cell researchers still face.[17] Many nations currently have moratoria on either ES cell research or the production of new ES cell lines. Because of their combined abilities of unlimited expansion and pluripotency, embryonic stem cells remain a theoretically potential source for regenerative medicine and tissue replacement after injury or disease.

Fetal

Fetal stem cells are primitive cell types found in the organs of fetuses.[18] The classification of fetal stem cells remains unclear and this type of stem cell is currently often grouped into an adult stem cell. However, a more clear distinction between the two cell types appears necessary.

Adult

The term adult stem cell refers to any cell which is found in a developed organism that has two properties: the ability to divide and create another cell like itself and also divide and create a cell more differentiated than itself. Also known as somatic (from Greek Σωματικóς, "of the body") stem cells and germline (giving rise to gametes) stem cells, they can be found in children, as well as adults.[19]

Pluripotent adult stem cells are rare and generally small in number but can be found in a number of tissues including umbilical cord blood.[20] A great deal of adult stem cell research has focused on clarifying their capacity to divide or self-renew indefinitely and their differentiation potential.[21] In mice, pluripotent stem cells are directly generated from adult fibroblast cultures. Unfortunately, many mice don't live long with stem cell organs.[22]

Most adult stem cells are lineage-restricted (multipotent) and are generally referred to by their tissue origin (mesenchymal stem cell, adipose-derived stem cell, endothelial stem cell, etc.).[23][24]

Adult stem cell treatments have been successfully used for many years to treat leukemia and related bone/blood cancers through bone marrow transplants.[25] Adult stem cells are also used in veterinary medicine to treat tendon and ligament injuries in horses.[26]

The use of adult stem cells in research and therapy is not as controversial as embryonic stem cells, because the production of adult stem cells does not require the destruction of an embryo. Additionally, because in some instances adult stem cells can be obtained from the intended recipient, (an autograft) the risk of rejection is essentially non-existent in these situations. Consequently, more US government funding is being provided for adult stem cell research.[27]

Amniotic

Multipotent stem cells are also found in amniotic fluid. These stem cells are very active, expand extensively without feeders and are not tumorogenic. Amniotic stem cells are multipotent and can differentiate in cells of adipogenic, osteogenic, myogenic, endothelial, hepatic and also neuronal lines.[28] All over the world, universities and research institutes are studying amniotic fluid to discover all the qualities of amniotic stem cells, and scientist such as Anthony Atala[29][30] and Giuseppe Simoni [31][32][33] have discovered important results.

From an ethical point of view, stem cells from amniotic fluid can solve a lot of problems, because it's possible to catch amniotic stem cells without destroying embryos. For example, the Vatican newspaper "Osservatore Romano" called amniotic stem cell "the future of medicine".[34]

It's possible to collect amniotic stem cells for donors or for autologuous use: the first US amniotic stem cells bank [35][36] opened in Medford, MA, by Biocell Center Corporation [37][38][39] and collaborates with various hospitals and universities all over the world.[40]

Induced pluripotent

These are not adult stem cells, but rather reprogrammed cells (e.g. epithelial cells) given pluripotent capabilities. Using genetic reprogramming with protein transcription factors, pluripotent stem cells equivalent to embryonic stem cells have been derived from human adult skin tissue.[41][42][43] Shinya Yamanaka and his colleagues at Kyoto University used the transcription factors Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4[41] in their experiments on cells from human faces. Junying Yu, James Thomson, and their colleagues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison used a different set of factors, Oct4, Sox2, Nanog and Lin28,[41] and carried out their experiments using cells from human foreskin.

As a result of the success of these experiments, Ian Wilmut, who helped create the first cloned animal Dolly the Sheep, has announced that he will abandon nuclear transfer as an avenue of research.[44]

Lineage

To ensure self-renewal, stem cells undergo two types of cell division (see Stem cell division and differentiation diagram). Symmetric division gives rise to two identical daughter cells both endowed with stem cell properties. Asymmetric division, on the other hand, produces only one stem cell and a progenitor cell with limited self-renewal potential. Progenitors can go through several rounds of cell division before terminally differentiating into a mature cell. It is possible that the molecular distinction between symmetric and asymmetric divisions lies in differential segregation of cell membrane proteins (such as receptors) between the daughter cells.[45]

An alternative theory is that stem cells remain undifferentiated due to environmental cues in their particular niche. Stem cells differentiate when they leave that niche or no longer receive those signals. Studies in Drosophila germarium have identified the signals dpp and adherens junctions that prevent germarium stem cells from differentiating.[46][47]

The signals that lead to reprogramming of cells to an embryonic-like state are also being investigated. These signal pathways include several transcription factors including the oncogene c-Myc. Initial studies indicate that transformation of mice cells with a combination of these anti-differentiation signals can reverse differentiation and may allow adult cells to become pluripotent.[48] However, the need to transform these cells with an oncogene may prevent the use of this approach in therapy.

Challenging the terminal nature of cellular differentiation and the integrity of lineage commitment, it was recently determined that the somatic expression of combined transcription factors can directly induce other defined somatic cell fates; researchers identified three neural-lineage-specific transcription factors that could directly convert mouse fibroblasts (skin cells) into fully-functional neurons. This "induced neurons" (iN) cell research inspires the researchers to induce other cell types implies that all cells are totipotent: with the proper tools, all cells may form all kinds of tissue.[49]

Treatments

Medical researchers believe that stem cell therapy has the potential to dramatically change the treatment of human disease. A number of adult stem cell therapies already exist, particularly bone marrow transplants that are used to treat leukemia.[51] In the future, medical researchers anticipate being able to use technologies derived from stem cell research to treat a wider variety of diseases including cancer, Parkinson's disease, spinal cord injuries, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, and muscle damage, amongst a number of other impairments and conditions.[52][53] However, there still exists a great deal of social and scientific uncertainty surrounding stem cell research, which could possibly be overcome through public debate and future research, and further education of the public.

One concern of treatment is the possible risk that transplanted stem cells could form tumors and have the possibility of becoming cancerous if cell division went out of control.[54]

Stem cells, however, are already used extensively in research, and some scientists do not see cell therapy as the first goal of the research, but see the investigation of stem cells as a goal worthy in itself.[55]

Controversy surrounding research

). Induced neural stem cells: Not quite ready for prime time University of Wisconsin-Madison News</ref>

Research patents

The patents covering a lot of work on human embryonic stem cells are owned by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF). WARF does not charge academics to study human stem cells but does charge commercial users. WARF sold Geron Corp. exclusive rights to work on human stem cells but later sued Geron Corp. to recover some of the previously sold rights. The two sides agreed that Geron Corp. would keep the rights to only three cell types. In 2001, WARF came under public pressure to widen access to human stem-cell technology.[56]

These patents are now in doubt as a request for review by the US Patent and Trademark Office has been filed by non-profit patent-watchdogs The Foundation for Taxpayer & Consumer Rights and the Public Patent Foundation as well as molecular biologist Jeanne Loring of the Burnham Institute. According to them, two of the patents granted to WARF are invalid because they cover a technique published in 1993 for which a patent had already been granted to an Australian researcher. Another part of the challenge states that these techniques, developed by James A. Thomson, are rendered obvious by a 1990 paper and two textbooks.

The outcome of this legal challenge is particularly relevant to the Geron Corp. as it can only license patents that are upheld.[57] dicks dicks dicks

Key research events

- 1908 - The term "stem cell" was proposed for scientific use by the Russian histologist Alexander Maksimov (1874–1928) at congress of hematologic society in Berlin. It postulated existence of haematopoietic stem cells.

- 1960s - Joseph Altman and Gopal Das present scientific evidence of adult neurogenesis, ongoing stem cell activity in the brain; like André Gernez, their reports contradict Cajal's "no new neurons" dogma and are largely ignored.

- 1963 - McCulloch and Till illustrate the presence of self-renewing cells in mouse bone marrow.

- 1968 - Bone marrow transplant between two siblings successfully treats SCID.

- 1978 - Haematopoietic stem cells are discovered in human cord blood.

- 1981 - Mouse embryonic stem cells are derived from the inner cell mass by scientists Martin Evans, Matthew Kaufman, and Gail R. Martin. Gail Martin is attributed for coining the term "Embryonic Stem Cell".

- 1992 - Neural stem cells are cultured in vitro as neurospheres.

- 1997 - Leukemia is shown to originate from a haematopoietic stem cell, the first direct evidence for cancer stem cells.

- 1998 - James Thomson and coworkers derive the first human embryonic stem cell line at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[58]

- 2000s - Several reports of adult stem cell plasticity are published.

- 2001 - Scientists at Advanced Cell Technology clone first early (four- to six-cell stage) human embryos for the purpose of generating embryonic stem cells.[59]

- 2003 - Dr. Songtao Shi of NIH discovers new source of adult stem cells in children's primary teeth.[60]

- 2004–2005 - Korean researcher Hwang Woo-Suk claims to have created several human embryonic stem cell lines from unfertilised human oocytes. The lines were later shown to be fabricated.

- 2005 - Researchers at Kingston University in England claim to have discovered a third category of stem cell, dubbed cord-blood-derived embryonic-like stem cells (CBEs), derived from umbilical cord blood. The group claims these cells are able to differentiate into more types of tissue than adult stem cells.

- 2005 - Researchers at UC Irvine's Reeve-Irvine Research Center are able to partially restore the ability of mice with paralyzed spines to walk through the injection of human neural stem cells.

- August 2006 - Rat Induced pluripotent stem cells: the journal Cell publishes Kazutoshi Takahashi and Shinya Yamanaka.[61]

- October 2006 - Scientists at Newcastle University in England create the first ever artificial liver cells using umbilical cord blood stem cells.[62][63]

- January 2007 - Scientists at Wake Forest University led by Dr. Anthony Atala and Harvard University report discovery of a new type of stem cell in amniotic fluid.[64] This may potentially provide an alternative to embryonic stem cells for use in research and therapy.[65]

- June 2007 - Research reported by three different groups shows that normal skin cells can be reprogrammed to an embryonic state in mice.[66] In the same month, scientist Shoukhrat Mitalipov reports the first successful creation of a primate stem cell line through somatic cell nuclear transfer[67]

- October 2007 - Mario Capecchi, Martin Evans, and Oliver Smithies win the 2007 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their work on embryonic stem cells from mice using gene targeting strategies producing genetically engineered mice (known as knockout mice) for gene research.[68]

- November 2007 - Human induced pluripotent stem cells: Two similar papers released by their respective journals prior to formal publication: in Cell by Kazutoshi Takahashi and Shinya Yamanaka, "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors",[69] and in Science by Junying Yu, et al., from the research group of James Thomson, "Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells":[70] pluripotent stem cells generated from mature human fibroblasts. It is possible now to produce a stem cell from almost any other human cell instead of using embryos as needed previously, albeit the risk of tumorigenesis due to c-myc and retroviral gene transfer remains to be determined.

- January 2008 - Robert Lanza and colleagues at Advanced Cell Technology and UCSF create the first human embryonic stem cells without destruction of the embryo[71]

- January 2008 - Development of human cloned blastocysts following somatic cell nuclear transfer with adult fibroblasts[72]

- February 2008 - Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse liver and stomach: these iPS cells seem to be more similar to embryonic stem cells than the previous developed iPS cells and not tumorigenic, moreover genes that are required for iPS cells do not need to be inserted into specific sites, which encourages the development of non-viral reprogramming techniques.[73]

- March 2008-The first published study of successful cartilage regeneration in the human knee using autologous adult mesenchymal stem cells is published by clinicians from Regenerative Sciences[74]

- October 2008 - Sabine Conrad and colleagues at Tübingen, Germany generate pluripotent stem cells from spermatogonial cells of adult human testis by culturing the cells in vitro under leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) supplementation.[75]

- 30 October 2008 - Embryonic-like stem cells from a single human hair.[76]

- 1 March 2009 - Andras Nagy, Keisuke Kaji, et al. discover a way to produce embryonic-like stem cells from normal adult cells by using a novel "wrapping" procedure to deliver specific genes to adult cells to reprogram them into stem cells without the risks of using a virus to make the change.[77][78][79] The use of electroporation is said to allow for the temporary insertion of genes into the cell.[80][81][82][83]

- 28 May 2009 Kim et al. announced that they had devised a way to manipulate skin cells to create patient specific "induced pluripotent stem cells" (iPS), claiming it to be the 'ultimate stem cell solution'.[84]

See also

- The American Society for Cell Biology

- California Institute for Regenerative Medicine

- Genetics Policy Institute

- Cancer stem cells

- Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPS Cell)

- Meristem

- Plant stem cells

- Stem cell marker

References

- ^ Becker AJ, McCulloch EA, Till JE (1963). "Cytological demonstration of the clonal nature of spleen colonies derived from transplanted mouse marrow cells". Nature. 197: 452–4. doi:10.1038/197452a0. PMID 13970094.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Siminovitch L, McCulloch EA, Till JE (1963). "The distribution of colony-forming cells among spleen colonies". Journal of Cellular and Comparative Physiology. 62: 327–36. doi:10.1002/jcp.1030620313. PMID 14086156.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tuch BE (2006). "Stem cells—a clinical update". Australian Family Physician. 35 (9): 719–21. PMID 16969445.

- ^ a b c d e f Hans R. Schöler (2007). "The Potential of Stem Cells: An Inventory". In Nikolaus Knoepffler, Dagmar Schipanski, and Stefan Lorenz Sorgner (ed.). Humanbiotechnology as Social Challenge. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 28. ISBN 0754657558.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn13=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mitalipov S, Wolf D (2009). "Totipotency, pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming". Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 114: 185–99. doi:10.1007/10_2008_45. PMC 2752493. PMID 19343304.

- ^ Ulloa-Montoya F, Verfaillie CM, Hu WS (2005). "Culture systems for pluripotent stem cells". J Biosci Bioeng. 100 (1): 12–27. doi:10.1263/jbb.100.12. PMID 16233846.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Friedenstein AJ, Deriglasova UF, Kulagina NN, Panasuk AF, Rudakowa SF, Luria EA, Ruadkow IA (1974). "Precursors for fibroblasts in different populations of hematopoietic cells as detected by the in vitro colony assay method". Exp Hematol. 2 (2): 83–92. PMID 4455512.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Friedenstein AJ, Gorskaja JF, Kulagina NN (1976). "Fibroblast precursors in normal and irradiated mouse hematopoietic organs". Exp Hematol. 4 (5): 267–74. PMID 976387.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "New Stem-Cell Procedure Doesn't Harm Embryos, Company Claims". Fox News. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "Mouse Embryonic Stem (ES) Cell Culture-Current Protocols in Molecular Biology".[dead link]

- ^ "Culture of Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESC)". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^

Chambers I, Colby D, Robertson M; et al. (2003). "Functional expression cloning of Nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells". Cell. 113 (5): 643–55. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00392-1. PMID 12787505.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF; et al. (2005). "Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells". Cell. 122 (6): 947–56. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. PMID 16153702.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Adewumi O, Aflatoonian B, Ahrlund-Richter L; et al. (2007). "Characterization of human embryonic stem cell lines by the International Stem Cell Initiative". Nat. Biotechnol. 25 (7): 803–16. doi:10.1038/nbt1318. PMID 17572666.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Thomson J, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro S, Waknitz M, Swiergiel J, Marshall V, Jones J (1998). "Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts". Science. 282 (5391): 1145–7. doi:10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. PMID 9804556.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ron Winslow (2009). "First Embryonic Stem-Cell Trial Gets Approval from the FDA". The Wall Street Journal. 23 January 2009.

- ^

Wu DC, Boyd AS, Wood KJ (2007). "Embryonic stem cell transplantation: potential applicability in cell replacement therapy and regenerative medicine". Front Biosci. 12: 4525–35. doi:10.2741/2407. PMID 17485394.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

editors, Ariff Bongso & Eng Hin Lee ; forewords by Sydney Brenner & Philip Yeo. (2005). Stem Cells: From Benchtop to Bedside. World Scientific. ISBN 981-256-126-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL; et al. (2002). "Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow". Nature. 418 (6893): 41–9. doi:10.1038/nature00870. PMID 12077603.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Ratajczak MZ, Machalinski B, Wojakowski W, Ratajczak J, Kucia M (2007). "A hypothesis for an embryonic origin of pluripotent Oct-4(+) stem cells in adult bone marrow and other tissues". Leukemia. 21 (5): 860–7. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404630. PMID 17344915.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gardner RL (2002). "Stem cells: potency, plasticity and public perception". Journal of Anatomy. 200 (3): 277–82. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00029.x. PMC 1570679. PMID 12033732.

- ^ Takahashi K, Yamanaka S (2006). "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors". Cell. 126 (4): 663–76. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. PMID 16904174.

- ^

Barrilleaux B, Phinney DG, Prockop DJ, O'Connor KC (2006). "Review: ex vivo engineering of living tissues with adult stem cells". Tissue Eng. 12 (11): 3007–19. doi:10.1089/ten.2006.12.3007. PMID 17518617.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Gimble JM, Katz AJ, Bunnell BA (2007). "Adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medicine". Circ Res. 100 (9): 1249–60. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000265074.83288.09. PMID 17495232.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bone Marrow Transplant".

- ^ Kane, Ed (2008-05-01). "Stem-cell therapy shows promise for horse soft-tissue injury, disease". DVM Newsmagazine. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ "Stem Cell FAQ". US Department of Health and Human Services. 2004. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^

P. De Coppi, G Barstch, Anthony Atala (2007). "Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy". Nature Biothecnology. 25 (5): 100–106. doi:10.1038/nbt1274. PMID 17344915.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. "Online NewsHour: Update | Amniotic Fluid Yields Stem Cells | January 8, 2007". PBS. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "Public : Stem Cell Briefings". ISSCR. 2008-03-21. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ National Institute of Healt

- ^ (Lancet, 1983)

- ^ "Biocell picks Massachusetts to house North American headquarters - Related Stories - BIO SmartBrief". Smartbrief.com. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "Vatican newspaper calls new stem cell source 'future of medicine' :: Catholic News Agency (CNA)". Catholic News Agency. 2010-02-03. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "European Biotech Company Biocell Center Opens First U.S. Facility for Preservation of Amniotic Stem Cells in Medford, Massachusetts". Reuters. 2009-10-22. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "Europe's Biocell Center opens Medford office - Daily Business Update - The Boston Globe". Boston.com. 2009-10-22. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ Track, Inside (2009-10-22). "The Ticker". BostonHerald.com. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ Biocell opens amniotic stem cell bank

- ^ "News » World's First Amniotic Stem Cell Bank Opens In Medford". wbur.org. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "Biocell Center Corporation Partners with New England's Largest Community-Based Hospital Network to Offer a Unique... - MEDFORD, Mass., March 8 /PRNewswire/". Massachusetts: Prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ a b c "Making human embryonic stem cells". The Economist. 2007-11-22.

- ^ Madeleine Brand, Joe Palca and Alex Cohen (2007-11-20). "Skin Cells Can Become Embryonic Stem Cells". National Public Radio.

- ^ "Breakthrough Set to Radically Change Stem Cell Debate". News Hour with Jim Lehrer. 2007-11-20.

- ^ "His inspiration comes from the research by Prof Shinya Yamanaka at Kyoto University, which suggests a way to create human embryo stem cells without the need for human eggs, which are in extremely short supply, and without the need to create and destroy human cloned embryos, which is bitterly opposed by the pro life movement."Roger Highfield (2007-11-16). "Dolly creator Prof Ian Wilmut shuns cloning". The Telegraph.

- ^

Beckmann J, Scheitza S, Wernet P, Fischer JC, Giebel B (2007). "Asymmetric cell division within the human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell compartment: identification of asymmetrically segregating proteins". Blood. 109 (12): 5494–501. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-11-055921. PMID 17332245.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Xie T, Spradling A (1998). "decapentaplegic is essential for the maintenance and division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary". Cell. 94 (2): 251–60. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81424-5. PMID 9695953.

- ^

Song X, Zhu C, Doan C, Xie T (2002). "Germline stem cells anchored by adherens junctions in the Drosophila ovary niches". Science. 296 (5574): 1855–7. doi:10.1126/science.1069871. PMID 12052957.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Takahashi K, Yamanaka S (2006). "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors". Cell. 126 (4): 663–76. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. PMID 16904174.

- ^ Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Südhof TC, Wernig M (2010-02-25). "Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors". Nature. 463 (7284): 1035–41. doi:10.1038/nature08797. PMC 2829121. PMID 20107439.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, Parkinson's,dick

Alzheimer's disease, osteoarthritis:

- Cell Basics: What are the potential uses of human stem cells and the obstacles that must be overcome before these potential uses will be realized?. In Stem Cell Information World Wide Web site. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009. cited Sunday, April 26, 2009

- Stem Cells Tapped to Replenish Organs thescientist.com, Nov 2000. By Douglas Steinberg

- ISRAEL21c: Israeli scientists reverse brain birth defects using stem cells[dead link] December 25, 2008. (Researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem-Hadassah Medical led by Prof. Joseph Yanai)

- Kang KS, Kim SW, Oh YH; et al. (2005). "A 37-year-old spinal cord-injured female patient, transplanted of multipotent stem cells from human UC blood, with improved sensory perception and mobility, both functionally and morphologically: a case study". Cytotherapy. 7 (4): 368–73. doi:10.1080/14653240500238160. PMID 16162459.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Strauer BE, Schannwell CM, Brehm M (2009). "Therapeutic potentials of stem cells in cardiac diseases". Minerva Cardioangiol. 57 (2): 249–67. PMID 19274033.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Stem Cells Tapped to Replenish Organs thescientist.com, Nov 2000. By Douglas Steinberg

- Hair Cloning Nears Reality as Baldness Cure WebMD November 2004

- Yen AH, Sharpe PT (2008). "Stem cells and tooth tissue engineering". Cell Tissue Res. 331 (1): 359–72. doi:10.1007/s00441-007-0467-6. PMID 17938970.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

- Drs. Gearhart and Kerr of Johns Hopkins University. April 4, 2001 edition of JAMA (Vol. 285, 1691-1693)

- Querida Anderson (2008-06-15). "Osiris Trumpets Its Adult Stem Cell Product". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. p. 13. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

(subtitle) Procymal is being developed in many indications, GvHD being the most advanced

- Gurtner GC, Callaghan, MJ and Longaker MT. 2007. Progress and potential for regenerative medicine. Annu. Rev. Med 58:299-312

- ^ Gahrton G, Björkstrand B (2000). "Progress in haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma". J Intern Med. 248 (3): 185–201. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00706.x. PMID 10971785.

- ^ Lindvall O (2003). "Stem cells for cell therapy in Parkinson's disease". Pharmacol Res. 47 (4): 279–87. doi:10.1016/S1043-6618(03)00037-9. PMID 12644384.

- ^ Goldman S, Windrem M (2006). "Cell replacement therapy in neurological disease". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 361 (1473): 1463–75. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1886. PMC 1664668. PMID 16939969.

- ^ "Stem-cell therapy: Promise and reality." Consumer Reports on Health 17.6 (2005): 8-9. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 5 Apr. 2010.

- ^ Wade N (2006-08-14). "Some Scientists See Shift in Stem Cell Hopes". New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ^ Regalado, Antonio, David P. Hamilton (July 2006). "How a University's Patents May Limit Stem-Cell Researcher." Wall Street Journal. Retrieved on July 24, 2006.

- ^ Kintisch, Eli (July 18, 2006) "Groups Target Stem Cell Patents." ScienceNOW Daily News. Retrieved August 15, 2006.

- ^

Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM (1998). "Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts". Science. 282 (5391). New York: 1145–7. doi:10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. PMID 9804556.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Cibelli JB, Lanza RP, West MD, Ezzell C (2001). "The first human cloned embryo". Scientific American.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shostak S (2006). "(Re)defining stem cells". Bioessays. 28 (3): 301–8. doi:10.1002/bies.20376. PMID 16479584.

- ^

Takahashi K, Yamanaka S (2006). "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors". Cell. 126 (4): 663–76. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. PMID 16904174.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

"Good news for alcoholics". Discover Magazine. 2007. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

. The Scotsman http://web.archive.org/web/20070203010452/http://news.scotsman.com/health.cfm?id=1608072006. Archived from the original on 2007-02-03.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^

De Coppi P, Bartsch G, Siddiqui MM; et al. (2007). "Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy". Nat Biotechnol. 25 (1): 100–6. doi:10.1038/nbt1274. PMID 17206138.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Karen Kaplan (8 January 2007). "Easy stem-cell source sparks interest: Researchers find amniotic fluid offers advantages". Boston Globe.

- ^ Cyranoski D (2007). "Simple switch turns cells embryonic". Nature. 447 (7145): 618–9. doi:10.1038/447618a. PMID 17554270.

- ^

Mitalipov SM, Zhou Q, Byrne JA, Ji WZ, Norgren RB, Wolf DP (2007). "Reprogramming following somatic cell nuclear transfer in primates is dependent upon nuclear remodeling". Hum Reprod. 22 (8): 2232–42. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem136. PMID 17562675.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Nobel prize in physiology or medicine 2007". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ^ Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S (2007). "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors" (PDF). Cell. 131 (5): 861–72. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. PMID 18035408.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA (2007). "Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells". Science. 318 (5858): 1917–20. doi:10.1126/science.1151526. PMID 18029452.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Chung; Klimanskaya, I; Becker, S; Li, T; Maserati, M; Lu, SJ; Zdravkovic, T; Ilic, D; Genbacev, O; et al. (2008). "Human embryonic stem cell lines generated without embryo destruction". Cell Stem Cell. 2 (2): 113. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.013. PMID 18371431.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^

French AJ, Adams CA, Anderson LS, Kitchen JR, Hughes MR, Wood SH (2008-01-17). "Development of human cloned blastocysts following somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) with adult fibroblasts" (PDF). Stem Cells Express. 26: 485. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0252. Archived from the original ([dead link]) on 2008-06-25.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Aoi T, Yae K, Nakagawa M; et al. (2008). "Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse liver and stomach cells". Science. 321 (5889): 699–702. doi:10.1126/science.1154884. PMID 18276851.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Centeno CJ, Busse D, Kisiday J, Keohan C, Freeman M, Karli D (2008). "Increased knee cartilage volume in degenerative joint disease using percutaneously implanted, autologous mesenchymal stem cells". Pain Physician. 11 (3): 343–53. ISSN 1533-3159. PMID 18523506.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Conrad S, Renninger M, Hennenlotter J; et al. (2008). "Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult human testis". Nature. 456 (7220): 344–9. doi:10.1038/nature07404. PMID 18849962.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Baker M (2008). "Embryonic-like stem cells from a single human hair". Nature Reports Stem Cells. doi:10.1038/stemcells.2008.142.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

Woltjen K, Michael IP, Mohseni P, Desai R, Mileikovsky M, Hämäläinen R, Cowling R, Wang W, Liu P, Gertsenstein M, Kaji K, Sung HK, Nagy A (2009-03-01). "piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells". Nature. 458 (7239): 766. doi:10.1038/nature07863. PMID 19252478.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Canadians make stem cell breakthrough". March 1, 2009. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- ^ "Researchers find new method for turning adult cells into stem cells". Amherst Daily News. Canadian Press. 2009-01-03. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ Ian Sample (2009-03-01). "Scientists' stem cell breakthrough ends ethical dilemma". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^

Kaji K, Norrby K, Paca A, Mileikovsky M, Mohseni P, Woltjen K (2009-03-01). "Virus-free induction of pluripotency and subsequent excision of reprogramming factors". Nature. 458 (7239): 771. doi:10.1038/nature07864. PMC 2667910. PMID 19252477.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee ASJ, Kahatapitiya P, Kramer B, Joya JE, Hook J, Liu R, Schevzov G, Alexander IE, McCowage G, Montarras D, Gunning PW, Hardeman EC (2009). "Methylguanine DNA methyltransferase-mediated drug resistance-based selective enrichment and engraftment of transplanted stem cells in skeletal muscle". Stem Cells. 27 (5): 1098–1108. doi:10.1002/stem.28. PMID 19415780.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sample I (1 March 2009). "Scientists' stem cell breakthrough ends ethical dilemma". The Guardian.

- ^

Kim D, Kim CH, Moon JI, Chung YG, Chang MY, Han BS, Ko S, Yang E, Cha KY, Lanza R, Kim KS (27 May 2009). "Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins". Cell Stem Cell. 4 (6): 472–6. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.005. PMC 2705327. PMID 19481515.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (cited in lay summary, not read)

External links

- General

- Tell Me About Stem Cells: Quick and simple guide explaining the science behind stem cells

- Stem Cell Basics

- Nature Reports Stem Cells: Introductory material, research advances and debates concerning stem cell research.

- Understanding Stem Cells: A View of the Science and Issues from the National Academies

- Scientific American Magazine (June 2004 Issue) The Stem Cell Challenge

- Scientific American Magazine (July 2006 Issue) Stem Cells: The Real Culprits in Cancer?

- Andrew Siegel. "Ethics of Stem Cell Research". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy

- How stem cells make skin | physorg.com

- Peer-reviewed journals