Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2009 November 26

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < November 25 | << Oct | November | Dec >> | November 27 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

November 26[edit]

age of atoms[edit]

Is there a difference between an atom of carbon when it was created billions of years ago and one now that is billions of years old? In other words are carbon atoms mortal and if so over what time scale do they show any change? 71.100.11.112 (talk) 04:44, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Well there are different types of carbon atoms, or of any atom, called isotopes. According to our article Isotopes of Carbon, two of these isotopes are stable, meaning that they will last forever under ordinary conditions. The rest of the isotopes are "mortal" or unstable, the most famous of which is probably Carbon-14 which has a half-life of about 5703 years. When it "dies" or decays, it becomes a Nitrogen-14 atom, which is stable. Jkasd 04:59, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

Interesting...and what decays to become stable Carbon-12, or are we stuck with however many of them we started with? DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 05:02, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think that most of the Carbon-12 in the universe is due to the CNO cycle in stars. Jkasd 05:07, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- I am certainly no expert, but the answer to your question is "it depends." If the carbon atom is an unstable isotope (radioactive), it will spontaneously decay at a time, which in my understanding is quite random. There is a way to measure this decay, but it is not dependent on an individual atom. The measurement assumes that you have a mass of multiple unstable atoms of the same type. When half of the atoms have decayed (changed form into another atom), that is called the half life. Carbon decay is specifically significant; look at carbon dating, where people attempt to calculate age by what percentage of the estimated original unstable carbon isotopes remain in an object. As for the time scale, it varies from almost immeasurably small amounts of time to hundreds of thousands of years, depending on the atom. As for mortality, only living beings can be mortal, at least in my definition of the word. An atom, so far as anybody knows, has absolutely zero self awareness or thought process, and as such is abiotic. An atom is therefore neither mortal (it will die someday) or immortal (it will live forever). Also, theoretically if one returned the appropriate particles to a decayed atom, it would return to its unstable form (we can do that with some nuclear reactions). Finally, if you have two carbon atoms of the same isotope, but one is three billion years older than the other, I don't believe that there is any difference. I hope this gives you a start, and since I am not an expert I'm counting on other editors to correct me if I am wrong about something ;-). Falconusp t c 05:11, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think the talk of isotopes is a bit of a distraction. In either case, a billion year old atom is the same as a newly created atom. That is, a billion year old atom of C-12 is the same as a newly created one and a billion year old atom of C-14 (if you could find one) will be exactly the same as a newly created atom of C-14. So, no, they don't "age". The unstable ones do randomly decay, but not because they are old, just because of a random event happening. (Don't think of it like trees dying when they get old, but dying when they are randomly struck by lightning, regardless of age.) StuRat (talk) 05:30, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Ah... So then are we speaking of conservation of something... perhaps conservation of stability? 71.100.11.112 (talk) 06:03, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- See also radiocarbon dating.--Shantavira|feed me 06:57, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Radiocarbon dating determines the age of a sample or population of atoms, not the "age" of an individual atom. Individual atoms, as StuRat and Tango said, do not age (in the case of unstable isotopes this means that an atom/nucleus just before it decays is indistinguishable from one that has just been created). --Wrongfilter (talk) 09:49, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

However, StuRat is correct in stating that I am not referring to radioactive decay of unstable isotopes but to aging of stable isotopes or aging of any stable particle. If you insist on including unstable isotopes then the question applies only to an isotope atom between the time it is created and the time it transmutes such as an atom of carbon-14 before transmuting to nitrogen-14. It is during the time the atom has not transmuted which concerns me and that I reference rather than to the transmutation itself. However, I leave the question open so you can answer it any way you will - transmutation included or not. 71.100.11.112 (talk) 10:19, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- In that case, no. There is absolutely no ageing of atoms. An atom of a particular isotope of a particular element is identical to any other, there are no changes over time. There are some changes in energy levels, but they are fluctuations, not any consistent change - they take place over nanoseconds (or smaller timeframes) and are insignificant over longer timescales. --Tango (talk) 10:34, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- What else in the Universe including the Universe itself does not grow older or undergo changes we can attribute to aging? 71.100.11.112 (talk) 10:49, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Well, the universe itself certainly ages. It expands (ie. becomes less dense) and the Cosmic Microwave Background cools down (that is part of the expansion) and entropy increases. Atoms and sub-atomic particles don't age. Molecules don't really age, although some large ones change shape over time (although I don't know of any such changes that happen in a particular direction so could be considered ageing). Stars certainly age, as do geologically active planets and planets large enough not to have finished cooling and whole galaxies and clusters of galaxies. Small planets and asteroids pretty much stop ageing after a certain amount of time (a billion years, say). They may pick up a few extra impact craters, but that's about it, although I suppose the isotope ratios change over time as the time since the matter that built up the asteroid was created in a supernova increases. So, in conclusion, if you are willing to look very closely pretty much anything larger than an individual molecule probably ages in some way. To an extent, this is a matter of definitions, though - everything changes, but for some things we consider any change to make it a new thing. If we considered an atom that undergoes radioactive decay to remain the same atom, just in a different form, then even atoms age - as they get older, they move towards more stable forms. This is a very statistical form of ageing, there is no way of measuring the age of a single atom, but I suppose it would be a form of ageing. We usually consider it a new atom, though, so that is irrelevant. I apologise for the stream of consciousness - this was going to be a coherent answer when I started it! I hope it is still useful. --Tango (talk) 11:13, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- No need to apologize. The question begs the answer and I can imagine a stable particle aging completely within the entire duration of its creation especially if that time span is instantaneous. 71.100.11.112 (talk) 12:05, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Well, the universe itself certainly ages. It expands (ie. becomes less dense) and the Cosmic Microwave Background cools down (that is part of the expansion) and entropy increases. Atoms and sub-atomic particles don't age. Molecules don't really age, although some large ones change shape over time (although I don't know of any such changes that happen in a particular direction so could be considered ageing). Stars certainly age, as do geologically active planets and planets large enough not to have finished cooling and whole galaxies and clusters of galaxies. Small planets and asteroids pretty much stop ageing after a certain amount of time (a billion years, say). They may pick up a few extra impact craters, but that's about it, although I suppose the isotope ratios change over time as the time since the matter that built up the asteroid was created in a supernova increases. So, in conclusion, if you are willing to look very closely pretty much anything larger than an individual molecule probably ages in some way. To an extent, this is a matter of definitions, though - everything changes, but for some things we consider any change to make it a new thing. If we considered an atom that undergoes radioactive decay to remain the same atom, just in a different form, then even atoms age - as they get older, they move towards more stable forms. This is a very statistical form of ageing, there is no way of measuring the age of a single atom, but I suppose it would be a form of ageing. We usually consider it a new atom, though, so that is irrelevant. I apologise for the stream of consciousness - this was going to be a coherent answer when I started it! I hope it is still useful. --Tango (talk) 11:13, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- What else in the Universe including the Universe itself does not grow older or undergo changes we can attribute to aging? 71.100.11.112 (talk) 10:49, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- There are particles that are 'immune' to time: massless particles like photons that travel at the speed of light and therefore experience no time. Fences&Windows 12:16, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Massless particles seem to be problematic: c = (1/M)*(M*E)^(1/2) (excuse the plain text form) 71.100.11.112 (talk) 13:06, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- I'm not sure where that formula came from, E=mc^2 rearranges to c=(E/m)^(1/2). While that looks problematic, that formula is for rest energy and massless particles can never be at rest, so the problem never comes up. If you interpret m as relativistic mass then that formula does give you the energy of the photon (but only because the relativistic mass is calculated using that formula!). --Tango (talk) 13:33, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Massless particles seem to be problematic: c = (1/M)*(M*E)^(1/2) (excuse the plain text form) 71.100.11.112 (talk) 13:06, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- The article you need to read, I think, is indistinguishability, at least up to the point before it launches into all the wave mechanics notation. When discussing particles at the quantum level, the concept of individual particles with individual identities starts to lose its meaning. We cannot tell, even in principle, which particles are the oldest because separated particles are a misconception. It is a bit like asking which is the oldest wave in the sea. SpinningSpark 12:54, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

Blackholes don't age. Dauto (talk) 13:12, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- They decay - see Hawking radiation. They also absorb background radiation (which any star sized or larger black holes will do more of at the moment than they radiate). --Tango (talk) 13:33, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, they decay, but as pointed out above by others, decaying is not the same thing as ageing. In other words: an old blackhole is indistuinguishable from an young one, as long as they have the same mass, charge, and angular momentum. see the no hair theorem. Dauto (talk) 14:26, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Having recently sat through a NASA lecture about interplanetary petrology, I may have some insights. The definition of "age" of a "thing" is always a little ambiguous when dealing with cosmogenic timescales. Technically speaking, (actually, not technically speaking at all), according to our best understanding of the universe, everything always existed and always will exist (although even this one gets debated by the really nitpicky cosmologists. So when you want to know the "age of a thing", what you really are asking is "how long since ____ happened to these atoms?" The blank can be filled in with a lot of complicated particle physics, geology, etc. The actual atoms are the same ones that came out of stars (usually); but even if they are not, the subatomic particles they are made of are the same ones that came out of stars; and so on. So, Instead of asking the "age of an atom," it is really better to ask "how long has this rock contained these molecules", "how long has this molecule contained these atoms", "how long since this atom mixed with these other atoms that are in the same molecule," or "how long since the protons of this atom all stuck together?" These are more precise questions and they're much easier to get exact-ish years.

- But, moving past some moot details, in the beginning there was a great infinitely dense mixture of undifferentiated energy and matter that obeyed the laws of General Relativity. All this muck swirled around in a sort of mind-bending cosmic singularity, but suddenly it started to break symmetry, and various types of subnuclear particles manifested themselves and obeyed different force laws, and it became possible to identify those which were matter-like and those which were particle-like carriers of forces that had just started to be identifiable. So, by now, all the matter and energy in the universe "existed" - and strictly speaking, everything is this old (13 billion years, often quoted with more precision in case you want to calibrate your calendar). At this early stage, nothing was an atom yet, let alone an identifiable hunk of space-debris or rock or self-locomotive, talking, carbonaceous life. Nonetheless, everything is "this old", insofar as its primordial cosmogenic ancestors came from this material.

- Anyway, flashing forward a few hundred million boring years, past the formation of the proto-nuclei and arriving at the plasma-like single protons swirling around in space, we get to stellar formation of the first round, in which hydrogen squishes together and stellar nucleosynthesis produces the standard spectrum of nuclei (atoms) that are found in almost everything we observe in space. So from some standpoint, all the atoms are really this old (neglecting, of course, a tiny but relevant fraction of nuclei which were synthesized in Big Bang's first few moments before the expansion brought the density below critical levels). Many, but not all, of the atomic nuclei are this old.

- A key thing happens here: probably, this star extincts itself, blows out all these atoms somewhere else, and they accrete in a new cloud or disc, the solar nebula or solar disc. These atoms are all floating around, but they begin to gravitationally self-attract, and finally compress in to start the formation of Sol. This is another unique age for all the rocks we find in space, because at this point, differentiation becomes relevant (e.g. the melting of rock by gravitational force). Gravity-based melting distills out the heavy and light nuclei, and so a benchmark of separated-nuclei concentrations is present. This is our "baseline" particle-ratio for heavy-nucleus radioisotope dating, because after this point, fractionation causes different rocks to have different concentrations of things. And once rocks sink into a convective melting process inside a planet, complete with metamorphic rock formation, all bets are off as far as where an individual atom will go.

- Finally, once a planetary rock makes its way to the surface, the rock begins to weather and erode, and oxidize (depending on the planet). So we can see an exchange of material again taking place; and we can date the age of this interaction.

- All told, it's really the same material getting mixed up over and over again; but at different timescales, different amounts of mixing happen. Over the lifespan of the universe, a single atom has progressed from an undifferentiated Planck soup into a Hydrogen atom into a complex nucleus into a fully-grown atom with its own electrons; and finally, it found other atoms and formed a molecule with those; and those molecules might have changed around a lot (and even the atomic nuclei might have shattered once or twice); and the large chunks of molecules probably convected a lot inside of a planet, and then probably eroded a whole lot at the surface; so the "age" is whatever you want to define it to be: the time since ____ last happened. Nimur (talk) 15:48, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Are you saying that while the bricks don't age the mortar and the building does? 71.100.11.112 (talk) 20:26, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

Both analog and digital possible?[edit]

Are there any FTA receivers which can receive both analog and digital satellite television? --84.61.167.221 (talk) 14:07, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think that they exist, but there is so little analog on satellite that it is probably not worthwhile. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 09:19, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

Sun looks different in size[edit]

Is there a scientific explanation for the reason we seen the Sun bigger in size during sunrise/sunset than in the mid-noon. I might be wrong but many have been asking this.--Email4mobile (talk) 14:53, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- See moon illusion. Gandalf61 (talk) 14:59, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Thanks a lot, Gandalf61.--Email4mobile (talk) 15:09, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- It's a very powerful illusion. I work in computer graphics and one task I've been handling recently is drawing the sun and moon realistically in computer games. When I calculate the mathematically correct sizes to draw them, they look ridiculously small because that moon illusion works in reverse on a computer screen. I had to draw them both at four times the realistic size in order to please the majority of the 30 or so co-workers I polled for their judgement of the right size! I find this deeply disturbing to my sense of "doing it right" - so I eventually compromised at three times the correct size. SteveBaker (talk) 17:26, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- I've read the moon illusion, but couldn't get a final explanation for that phenomenon. Can you give me a conclusion for that?--Email4mobile (talk) 17:36, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- It's a surprisingly powerful illusion - nearly everyone overestimates the size of the moon - but you can use the "Can you cover the moon with the tip of your pinky finger at arms-length?" test (yes, you can) to convince yourself that sun & moon are indeed the same size no matter where they are in the sky. Basically - when the moon (or sun or whatever) is far above the horizon, you have no context for judging it's size - when it's close to the horizon, you have other objects to compare it against - since it's "behind" everything else, your brain registers that it's a long way away - since it's obviously larger than things like houses and trees - it looks gigantic (which is fair because it IS gigantic). SteveBaker (talk) 18:33, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- So it is a state of relativistic views rather than light intensity effect. Before, I asked and before reading about it, I was thinking it was due to different light intensity during the different times. Thanks SteveBaker.--Email4mobile (talk) 21:33, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- I wouldn't call it relativistic, I would call it relative - just to avoid ambiguity about the actual effect. Nimur (talk) 22:38, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

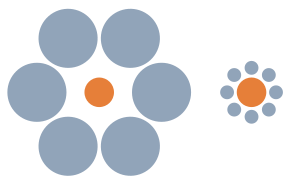

- Right - the image at right really explains it well. It's called "The Ebbinghaus illusion". Imagine that the orange dot is the moon - but with the largeness of the sky it looks smaller than with the small details of the horizon. SteveBaker (talk) 23:32, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Doesn't the atmosphere have a sort of magnifying effect as well? Granted it would be fairly small, but perhaps noticeable. Googlemeister (talk) 15:32, 30 November 2009 (UTC)

- Right - the image at right really explains it well. It's called "The Ebbinghaus illusion". Imagine that the orange dot is the moon - but with the largeness of the sky it looks smaller than with the small details of the horizon. SteveBaker (talk) 23:32, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- I wouldn't call it relativistic, I would call it relative - just to avoid ambiguity about the actual effect. Nimur (talk) 22:38, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

How big can a Thanksgiving turkey be?[edit]

The Wikipedia articles on turkeys don't say how big a Thanksgiving turkey can be, and searching around on the Internet did not tell me, either. I know that the supermarket has turkeys larger than 24 pounds, but how big can they be? --DThomsen8 (talk) 14:56, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Is there some reason Thanksgiving turkeys are different from normal turkeys? Googling suggests a world record was set at 86 pounds - Wikipedia blocks the link because apparently it's spam. Are you perhaps talking about specific weights at which turkeys are commercially sold? Vimescarrot (talk) 15:34, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- The human variety may weigh more. 71.100.11.112 (talk) 15:52, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Googling around suggests that birds as large as 40lbs can be bought commercially - but almost all of the "How long does it take to cook" guides top out at 30lbs. Many of those guides recommend buying two smaller turkeys when you need more than 18lbs because it's easier to control the cooking process. SteveBaker (talk) 17:21, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Turkeys have been bred over generations to be larger and larger. Today they are so big they can no longer mate on their own, and must be artificially inseminated. They are also starting to have problems walking. To make them larger would probably require too much human intervention to make it cost effective. Ariel. (talk) 19:30, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- With the above mentioned cooking control issue it seems like even large kitchens might prefer smaller turkeys. Perhaps GM will find a way to make legs stronger or to eliminate unwanted parts. I dare to imagine what kind of "turkey" science could come up with if it really went to work. 71.100.11.112 (talk) 19:39, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Wouldn't that simply be growing meat in a lab. Remove all the unwanted parts - the stuff that isn't meat. You are left with meat. It isn't too hard to imagine. It also means that no turkeys would be killed to produce Thanksgiving dinners. I know - that is purely evil GM thinking. Thanksgiving without killing turkeys - I dare to imagine what kind of freak holiday that would be. -- kainaw™ 23:10, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- The Space Merchants (1952) features 'Chicken Little' which is exactly what Kainaw suggests (but the article is currently under maintenance, and presumably for that reason doesn't mention Chicken Little at present). --ColinFine (talk) 00:02, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- When I was a kid, my family grew a turkey that weighed 50 lbs dressed out. A turkey that size will not fit into a standard oven. Googlemeister (talk) 15:34, 30 November 2009 (UTC)

- The Space Merchants (1952) features 'Chicken Little' which is exactly what Kainaw suggests (but the article is currently under maintenance, and presumably for that reason doesn't mention Chicken Little at present). --ColinFine (talk) 00:02, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

hoax? Bulgarian scientist claims alien contact[edit]

So what is this all about? There is a scientist called Lachezar Georgiev Filipov, who has a CV here, hosted by the Space Research Institute of Bulgaria. Today he is in the news for claiming that "aliens are already among us". Is this Bulgarian National Tease the Rest of the World Day? Or is it a reverse practical joke, designed to extract more funding -- "see, the public will believe anything, so we need mass education"? Or has his name been taken in vain? Or could it be that he actually believes this? BrainyBabe (talk) 16:22, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- How very interesting, I wonder if we should have messages relayed to us via 'the power of thought' as another one of the WP:Reliable sources Wikipedia uses? ;-) Dmcq (talk) 16:37, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Is it wrong that I laughed at

- "PROFESIONAL TRAINING

- [...]

- 1981 Language qualification - England

- in his CV? 86.144.145.238 (talk) 16:41, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, I noticed that too. The website of the institute looks c. 1997 -- in fact, I thought it might be a fake, but if so, someone has gone to many many pages of trouble. BrainyBabe (talk) 16:45, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Lots of reputable science figures end up promoting crackpot ideas. Initially starting with a scientific-like approach, these people usually devolve into disreputable science figures, by way of ignoring factual evidence and the scientific method. Take a look, for example, at Edgar Mitchell. His outlandish views have put him outside the main fray of NASA and at odds with most scientific thought. Nimur (talk) 16:55, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- A little tracing of sources shows that everyone is ultimately reporting something that appeared in Novinar, a Bulgarian newspaper. You can read Novinar's interview with Filipov in broken English using Google translate: here. The blurb at the beginning suggests there is an earlier (Monday?) Novinar article publishing his thoughts, which sparked all of this. I cannot find this earlier article online, but then I have no grip on Bulgarian or the Cyrillic script. 86.144.145.238 (talk) 17:06, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- In which case, should we rope in some Language Desks regulars to comment on the English reporting compared to what was said in Bulgarian? 86.140.174.66 (talk) 17:16, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- How could the translation be intentionally mistranslated or misconstrued? Google translate is a purely automated tool, so there's no people involved in the translation process that could be intentionally malicious in the process.

- Having read the automated English translation of the Bulgarian article, I see no evidence that would suggest that this is a hoax, or a joke, or that he doesn't genuinely believe it. He's just a scientist who wound up getting caught up in some bullshit. I think scientists as a whole are much less likely than the general public to get lured into believing nonsense like this, but it certainly does happen. Scientists are still just human. Red Act (talk) 17:59, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Well, he has carefully examined 130 crop circles and asked the Vatican about it - you can only take 'due diligence' so far.

- But to address the OP's question: I don't think we can accurately research his motives behind this announcement. If it's a hoax or a joke - it's a pretty pathetic one - maybe it was funnier in the original Bulgarian? He's claiming the messages are telepathic - and hearing voices in ones head (See Auditory hallucination) is a sign of schizophrenia or mania. It's perfectly possible that this guy has a real medical problem. As an effort to extract more funding? Well, if that was the intent - I think it may have backfired - the linked article says that the finance minister is discussing it with the prime minister...I don't think that's going to end positively. SteveBaker (talk) 17:14, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- From the Bulgarian interview, I don't get that Filipov thinks that he himself is getting telepathic messages through the crop circles, it's a woman by the name of Mariana Vezneva. Filipov has just become one of Vezneva's followers. Vezneva's web site says that the "Teachers" materialized twice in her home, so if she's having hallucinations, they're not just auditory ones. Red Act (talk) 20:38, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- "Mr Filipov said that even the seat of the Catholic church, the Vatican, had agreed that aliens existed." Indeed, they agree, but they call them God, seraphim, cherubim, etc. --Cookatoo.ergo.ZooM (talk) 18:09, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

Translation of Bulgarian article: An anonymous Bulgarian editor has kindly and amazingly translated the article into readable English on the Language desk. Wikipedia:Reference_desk/Language#Bulgarian_Scientist. You can go there to read precisely what he said, including where he says some very strange things and also where he seems to have tried to investigate a fringe area vaguely scientifically. All very odd. Also, tantalising hints of at least one earlier article laying out some of this bizarre theories in more detail.

Props to the translator, who really exceeded expectations translating something so bizarre into something so accessible. 86.140.171.80 (talk) 05:31, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- Side note - it is great that Wikipedia can link up talent and interest to people in need. Thanks for the translation.

- Anyway, from a reading of the article, it looks like the scientist is being blacklisted for investigating a paranormal claim - it doesn't appear that he has taken a stance to believe or disbelieve any of the paranormal claims. Furthermore, it appears that he did it on his own time, and not through the auspices of the Bulgarian Academy of Science. As I mentioned earlier, I think it's possibly a slander campaign to make this out to be much more sinister, and paint the guy as a "nut-job". Clearly there's a political and financial angle to such a maneuver. I guess the moral of the story is that any scientist who wants to keep their job should avoid so much as mentioning the paranormal, lest the media should find out about it. Nimur (talk) 16:08, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- It is very important that you do not panic. Be assured that reliable scientists with white coats and horn rimmed spectacles have the situation under complete control. So keep calm. There is absolutely no substance in rumours you may hear that the all-encompassing mental field is sucking the brains out of our children. Crop rings do not exist. They have been proved to be hoaxes perpetrated by malicious farmers seeking to inflate the price of wheat, and they will be dealt with by

commando death squadsthe proper authorities. Furthermore, Bulgaria is a friendly country somewhere in a foreign place that is famous for its sunflower seeds and volleyball players, and it could never be taken over by aliens posing as mad professors without someone noticing. Even as we speak the CIA is only waiting for the clouds to clear so our Spy satellites can find exactly where Bulgaria is. Not only do telepathic aliens not exist, no telepathic alienamong those now held at Area 51 underground Sector 4shows any sign of understanding Bulgarian language. So there is no reason to panic. Wikipedia has an article on Bulgaria that may be helpful. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 10:20, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- I was asked by BrainyBabe to comment on the general situation here. In my very humble opinion, the whole story is not notable enough for us to discuss it. It is typical for the media in Bulgaria that they should include materials on aliens, paranormal phenomena and events, etc. from time to time. See for example this almost humorous reportage by bTV, the most influential television channel in Bulgaria, telling of an alien creature reportedly noticed in Varna. There are many people everywhere who claim to have communicated with extraterrestrials, and professor Filipov is just one of them, with my greatest respect to him. Searching Google for his name gives mostly interviews with him and articles by him, such as: Lachezar Filipov: UFOs have been witnessed in Bulgaria several times, Professor Lachezar Filipov, astrophysicist: Our civilisation is not yet ready for a contact, Bulgarian cosmologist: There is nothing to worry about as long as we are under the control of God and so on. --62.204.152.181 (talk) 16:03, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- Thank you again, o anonymous Bulgarian! Your putting the hoo-ha in context is valuable, especially the new links you provide. Your good work is appreciated. BrainyBabe (talk) 21:48, 29 November 2009 (UTC)

- There have been many compilations of reputable alien sightings, but many UFOs could be secret government millitary craft such as the Avrocar. One such compilation is Project Blue Book, and the British and Belgian government recently released information on possible alien sightings. There was also a 1996 case where a large 2/3 wide spacecraft was indpendently reported by about two dozen witnesses. ~AH1(TCU) 02:06, 2 December 2009 (UTC)

How does the body sense temperature?[edit]

I don't mean, what does it do with the information, but the physical measurement used. I read Thermoregulation, Thermoception, and Homeostasis, and none of them mention it.

Temperature changes the speed of sound, the size of objects, the kinetic speed of gases, melting things, the speed of reactions, pressure in a container, electrical resistance. And yet none of those would seem to be measurable by the body. And accurately too - to less that .1 of a degree, and it's also tunable (fever) - how is it calibrated?

What physical thing does the body measure? I assume thermoregulation is tuned for accuracy, and thermoception for speed. Ariel. (talk) 18:53, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- To quote the Thermoception article, "The details of how temperature receptors work is still being investigated." :( If anyone does find refs for research on that, please add to the article. DMacks (talk) 21:00, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- There are specific neurons that sense heat -- they are cross-sensitive to capsaicin; there are also cold-sensing neurons, and these are cross-sensitive to menthol. That's why these and other items give us a "hot" or "cold" sensation. Perhaps what needs to be worked out and is still under investigation is how the body senses finer changes in temperature than basic hot + cold. It's possible, though, that the body just senses relative warmth of lack of warmth, just like the case of the three buckets (one with hot water, one with cold water, still a foot in each and after a minute, pour both contents into 3rd bucket, put both feet in and it feels hot for the foot that was in the cold and cold for the foot that was in the hot). DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 23:45, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Even just basic hot/cold (without any fine measurements), and even simpler: simply measuring if something is hotter or colder than the body - how? What physical thing does it measure? And accurately measuring body temperature with no reference, or method calibration has to be even harder, and I wonder both how it does that, and what physical change does it measure? Ariel. (talk) 00:32, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- It really isn't known (and, given somatosensation is the last sensory system where very little is understood at the molecular level, when it is fully worked out it will probably earn the scientists a Nobel Prize). Scientists are largely focusing in Transient receptor potential ion channels, such as the TRPV and TRPA (channel)s, as the candidate proteins that detect temperature. I happen to have some colleagues that are at the forefront of this research. Frustratingly, the detection of actual temperature appears to be mechanistically different from the detection of chemicals that we perceive as having temperature (such as menthol or capsaicin), which complicates matters. But, without giving away too much unpublished data, they appear to have narrowed down the precise parts of these proteins that are temperature sensitive. They are now trying to work out what exactly happens to these specific amino-acids when you change their ambient temperature. That should provide a clue to the exact physical characteristic that precipitates the molecular change. Come back and ask this question in about 5 years, and I expect we will be able to answer it more fully. Rockpocket 01:55, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- Thank you. At least now I know that it isn't known, and I should stop trying to find someone who knows. And I shall do just that, I'll put an entry in my calendar for 5 years from now, and I'll email you from your wikipedia page and ask how things are going. :) (Similey, but I really will.) Ariel. (talk) 04:14, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- It really isn't known (and, given somatosensation is the last sensory system where very little is understood at the molecular level, when it is fully worked out it will probably earn the scientists a Nobel Prize). Scientists are largely focusing in Transient receptor potential ion channels, such as the TRPV and TRPA (channel)s, as the candidate proteins that detect temperature. I happen to have some colleagues that are at the forefront of this research. Frustratingly, the detection of actual temperature appears to be mechanistically different from the detection of chemicals that we perceive as having temperature (such as menthol or capsaicin), which complicates matters. But, without giving away too much unpublished data, they appear to have narrowed down the precise parts of these proteins that are temperature sensitive. They are now trying to work out what exactly happens to these specific amino-acids when you change their ambient temperature. That should provide a clue to the exact physical characteristic that precipitates the molecular change. Come back and ask this question in about 5 years, and I expect we will be able to answer it more fully. Rockpocket 01:55, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- Even just basic hot/cold (without any fine measurements), and even simpler: simply measuring if something is hotter or colder than the body - how? What physical thing does it measure? And accurately measuring body temperature with no reference, or method calibration has to be even harder, and I wonder both how it does that, and what physical change does it measure? Ariel. (talk) 00:32, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- There are specific neurons that sense heat -- they are cross-sensitive to capsaicin; there are also cold-sensing neurons, and these are cross-sensitive to menthol. That's why these and other items give us a "hot" or "cold" sensation. Perhaps what needs to be worked out and is still under investigation is how the body senses finer changes in temperature than basic hot + cold. It's possible, though, that the body just senses relative warmth of lack of warmth, just like the case of the three buckets (one with hot water, one with cold water, still a foot in each and after a minute, pour both contents into 3rd bucket, put both feet in and it feels hot for the foot that was in the cold and cold for the foot that was in the hot). DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 23:45, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

harmful aspiration[edit]

Are societies which now are able to provide an abundance of food to everyone growing overweight due to the psychological effect of the aspiration to be wealthy and the fact that the wealthiest have become overweight? In other words if we aspired to break-even so to speak instead of aspiring to have wealth beyond our need would we find acquisition of normal weight to be the result of our ambition or the rule? 71.100.11.112 (talk) 20:36, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- Research has been published both indicating and refuting your assertion; e.g. Food insecurity is associated with increased risk of obesity (2003); and Obesity: the emerging cost of economic prosperity (2006). I searched Google Scholar for results with obesity and prosperity as my query. Nimur (talk) 22:57, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- I believe that the best explanation is simply that we evolved in a world without farming - where food was not abundant and where high-calorie foods were especially valuable to day-to-day survival. Hence, nothing in our biochemistry turns off the desire to eat or moderates our attraction to foods that are (in abundant quantities) harmful to us - but which were crucial to survival in early hominids. SteveBaker (talk) 23:27, 26 November 2009 (UTC)

- An important point I think is that it is not the wealthiest who have become overweight — not within a given society. Comparing countries we might find prosperous countries more overweight than economically ineffectual countries. But I would doubt that the wealthiest Americans represent the most overweight group of Americans. Bus stop (talk) 02:55, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- Also, our dogs and cats are overweight too - it's safe to assume that they don't have some psychological aspiration to become wealthy. They get obese because they are fed more of the wrong foods than their bodies need - and there is no biological imperative to stop eating after having eaten a healthy amount. Pet birds don't seem get obese (at least, I've never heard of an obese parrot!) - presumably because they DO have a built in biological mechanism to prevent them from over-eating and becoming to heavy to fly. Evolution does things like that! SteveBaker (talk) 03:27, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- Some studies have found that in affluent countries, the poor have the highest rates of obesity. For instance [1] Possibly because they are less able to buy fresh vegetables, more likely to eat highly processed foods. Or perhaps because they are less likely to sit down to carefully prepared meals at all. 75.41.110.200 (talk) 07:04, 27 November 2009 (UTC)

- Also, our dogs and cats are overweight too - it's safe to assume that they don't have some psychological aspiration to become wealthy. They get obese because they are fed more of the wrong foods than their bodies need - and there is no biological imperative to stop eating after having eaten a healthy amount. Pet birds don't seem get obese (at least, I've never heard of an obese parrot!) - presumably because they DO have a built in biological mechanism to prevent them from over-eating and becoming to heavy to fly. Evolution does things like that! SteveBaker (talk) 03:27, 27 November 2009 (UTC)