Casuariiformes

| Casuariiformes Temporal range: Possible Paleocene appearance.

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Southern cassowary | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae |

| Clade: | Novaeratitae |

| Order: | Casuariiformes (Sclater, 1880) Forbes, 1884[1] |

| Families | |

| Diversity | |

| 1 family, 4 genera (including 2 extinct), 9 species (including 5 extinct) | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

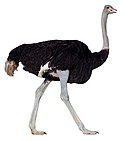

The Casuariiformes /kæsjuːˈæri.ɪfɔːrmiːz/ is an order of large flightless birds that has four surviving members: the three species of cassowary, and the only remaining species of emu. They are divided into either a single family, Casuariidae, or more typically two, with the emu splitting off into its own family, Dromaiidae.

All four living members are native to Australia-New Guinea,[3] but some possible extinct taxa occurred in other landmasses.

Systematics and evolution

[edit]

The emus form a distinct family, characterized by legs adapted for running. The total number of cassowary species described, based on minor differences in casque shape and color variations, formerly reached nine.[4] Now, however, only three species are recognized, and most authorities only acknowledge few subspecies or none at all.

The fossil record of casuariforms is interesting, but not very extensive. Regarding fossil species of Dromaius and Casuarius, see their genus pages. As with all ratites, there are several contested theories concerning their evolution and relationships.

Some Australian fossils initially believed to be from emus were recognized to represent a distinct genus, Emuarius,[a] which had a cassowary-like skull and femur and an emu-like lower leg and foot. In addition, the first fossils of mihirungs were initially believed to be from giant emus,[b] but these birds were completely unrelated.

It has been suggested[who?] that the South American genus Diogenornis was a casuariiform bird, instead of a member of the rheas, the current South American lineage of giant ground birds. If this were the case, not only would it extend the fossil range of this lineage to a wider region, but to a broader time span as well, since Diogenornis occurs in the late Paleocene and is among the earliest known ratites.[5] In the late 19th century, a fossil casuariid (Hypselornis) was named from India based on a single toe bone, however it was later shown to belong to a crocodilian.[6]

An especially interesting question regarding this order is whether emus or cassowaries are the more primitive form, if either. Emus are generally assumed to retain more ancestral features, in part because of their more modest coloration, but this does not necessarily have to be the case. The casuariiform fossil record is ambiguous, and the present knowledge of their genome is insufficient for comprehensive analysis. Resolving the cladistic issues will require combination of all these approaches, with at least the additional consideration of plate tectonics.

Taxonomy

[edit]Casuariiformes (Sclater, 1880) Forbes 1884[7][8][9]

- ?†Diogenornis - Alvarenga, 1983 (Paleocene of Brazil)

- †Diogenornis fragilis Alvarenga, 1983

- Casuariidae Kaup, 1847 (emus and cassowaries)

- †Emuarius Boles, 1992 (emuwaries) (Late Oligocene – Late Miocene)

- †Emuarius gidju (Patterson & Rich 1987) Boles, 1992

- †Emuarius guljaruba Boles, 2001

- Casuarius (Linnaeus 1758) Brisson, 1760 (cassowary)

- †Casuarius lydekkeri Rothschild, 1911 (Pygmy cassowary)

- Casuarius casuarius (Linnaeus, 1758) Brisson, 1760 (Southern cassowary)

- Casuarius unappendiculatus Blyth 1860 (Northern cassowary)

- Casuarius bennetti Gould, 1857 (Dwarf cassowary)

- †Emuarius Boles, 1992 (emuwaries) (Late Oligocene – Late Miocene)

- Dromaiidae Huxley, 1868 (modern emus)

- Dromaius Vieillot, 1816 (emus) (Middle Miocene – Recent)

- †Dromaius arleyekweke Yates & Worthy, 2019

- †Dromaius ocypus Miller, 1963

- Dromaius novaehollandiae (Latham, 1790) Vieillot 1816 (emu)

- †D. n. minor Spencer, 1906 (King Island/black emu)

- †D. n. baudinianus Parker, 1984 (Kangaroo Island/dwarf emu)

- †D. n. diemenensis (Jennings, 1827) Le Souef, 1907 (Tasmanian emu)

- D. n. novaehollandiae (Latham, 1790) (Australian emu)

- Dromaius Vieillot, 1816 (emus) (Middle Miocene – Recent)

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brand, S. (2008)

- ^ Brodkob, Pierce (1963). "Catalogue of fossil birds 1- Archaeopterygiformes through Ardeiformes". Biological Sciences, Bulletin of the Florida State Museum. 7 (4): 180–293. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ Clements, J (2007)

- ^ Lockyer, Norman (14 October 1875). Nature. Vol. 12. London, UK: Macmillan and Co. pp. 516–517.

- ^ Alvarenga, H. (2010). "Diogenornis fragilis Alvarenga, 1985, restudied: a South American ratite closely related to Casuariidae". [no journal cited].[full citation needed]

- ^ Lowe, P. R. (1929). "Some remarks on Hypselornis sivalensis Lydekker". Ibis. 71 (4): 571–576. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1929.tb08775.x.

- ^ Mikko's Phylogeny Archive [1] Haaramo, Mikko (2007). "PALEOGNATHIA- paleognathous modern birds". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ Paleofile.com (net, info) "Paleofile.com". Archived from the original on 2016-01-11. Retrieved 2015-12-30.. "Taxonomic lists- Aves". Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ [2] Archived 2016-10-05 at the Wayback Machine Perron, Richard (2010). "Taxonomy of the Genus Casuarius". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

References

[edit]- Boles, Walter E. (2001). "A new emu (Dromaiinae) from the Late Oligocene Etadunna Formation". Emu. 101 (4): 317–321. Bibcode:2001EmuAO.101..317B. doi:10.1071/MU00052. S2CID 1808852.

- Brands, Sheila (Apr 8, 2012). "Taxon: Order Casuariiformes". Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved Jun 17, 2012.

- Clements, James (2007). The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World (6 ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4501-9.

- Folch, A. (1992). "Family Casuariidae (Cassowaries)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jose (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. pp. 90–97. ISBN 84-87334-09-1.