Ubba: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

overhaul |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

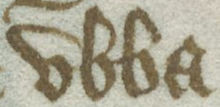

[[File:Harley MS 2278, folio 48v excerpt.jpg|thumb|"''Vbba''", Ubba's name as it appears in ''Harley MS 2278'', a fifteenth-century [[Middle English]] manuscript.<ref>[[#H4|Hervey 1907]] p. 458; [[#H5|Harley MS 2278]].</ref>]] |

|||

{{for|the Swedish band|UBBA (band)}} |

{{for|the Swedish band|UBBA (band)}} |

||

[[File:Harley MS 2278, folio 48v excerpt.jpg|thumb|alt=Refer to caption|right|Ubba's name as it appears on folio 48[[verso|v]] of British Library Harley 2278 (''Lives of Saints Edmund and Fremund''): "''{{lang|enm|Vbba}}''".<ref>[[#UBBAH4|Hervey (1907)]] p. 458; [[#UBBAH29|Horstmann (1881)]] p. 402 bk. 2 § 319; [[#UBBAH6|''Harley MS 2278'' (n.d.)]].</ref>]] |

|||

'''Ubba''', also known as '''Hubba''', '''Ubbe''', and '''Ubbi''', was a mid-ninth-century [[Viking]] chieftain and one of the commanders of the [[Great Heathen Army|Great Army]], a coalition of [[Norsemen|Norse]] warriors that in AD 865 invaded the [[History of Anglo-Saxon England|Anglo-Saxon]] kingdoms of [[Kingdom of Northumbria|Northumbria]], [[Mercia]], [[Kingdom of East Anglia|East Anglia]] and [[Wessex]]. According to a tradition recorded in [[Saga|Norse sagas]], he was one of the sons of [[Ragnar Lothbrok]]. |

|||

'''Ubba''' was a ninth-century [[Viking]], and one of the commanders of the [[Great Army (Viking)|Great Army]] that invaded [[Anglo-Saxon England]] in the 860s.{{#tag:ref|Since the 1990s, academics have accorded Ubba various personal names in English secondary sources: ''Huba'',<ref>[[#UBBAC17|Costambeys (2004b)]].</ref> ''Hubba'',<ref>[[#UBBAB1|Barrow (2016)]]; [[#UBBAB6|Bartlett (2016)]]; [[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]]; [[#UBBAJ1|Jordan, TRW (2015)]]; [[#UBBAM8|McTurk, R (2015)]]; [[#UBBAL2|Lapidge (2014)]]; [[#UBBAL7|Lazzari (2014)]]; [[#UBBAC12|Cammarota (2013)]]; [[#UBBAW18|Emons-Nijenhuis (2013)]]; [[#UBBAM4|Mills, R (2013)]]; [[#UBBAG17|Gigov (2011)]]; [[#UBBAP19|Pinner (2010)]]; [[#UBBAF4|Finlay (2009)]]; [[#UBBAR14|Ridyard (2008)]]; [[#UBBAR10|Rowe, EA (2008)]]; [[#UBBAM1|McTurk, R (2007)]]; [[#UBBAW3|Winstead (2007)]]; [[#UBBAM13|McTurk, R (2006)]]; [[#UBBAF9|Fjalldal (2003)]]; [[#UBBAS1|Schulenburg (2001)]]; [[#UBBAF12|Foot (2000)]]; [[#UBBAF14|Frederick (2000)]]; [[#UBBAH17|Halldórsson (2000)]]; [[#UBBAH21|Hayward (1999)]]; [[#UBBAK9|Keynes (1999)]]; [[#UBBAP1|Pulsiano (1999)]]; [[#UBBAW4|Whitelock (1996)]]; [[#UBBAG15|Gransden (1995)]]; [[#UBBAT12|Townsend (1994)]]; [[#UBBAR7|Rowe, E (1993)]].</ref> ''Ubba'',<ref>[[#UBBAC15|Coroban (2017)]]; [[#UBBAB1|Barrow (2016)]]; [[#UBBAB6|Bartlett (2016)]]; [[#UBBAG20|Gore (2016)]]; [[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]]; [[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]]; [[#UBBAM15|McGuigan (2015)]]; [[#UBBAP13|Pinner (2015)]]; [[#UBBAD2|Downham (2013a)]]; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]]; [[#UBBAP19|Pinner (2010)]]; [[#UBBAC13|Cawsey (2009)]]; [[#UBBAE1|Edwards, ASG (2009)]]; [[#UBBAF4|Finlay (2009)]]; [[#UBBAH5|Hayward (2009)]]; [[#UBBAR14|Ridyard (2008)]]; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]]; [[#UBBAM16|McLeod, S (2006)]]; [[#UBBAA10|Adams; Holman (2004)]]; [[#UBBAC17|Costambeys (2004b)]]; [[#UBBAC23|Crumplin (2004)]]; [[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]]; [[#UBBAH17|Halldórsson (2000)]]; [[#UBBAR11|Rigg (1996)]]; [[#UBBAG15|Gransden (1995)]]; [[#UBBAA15|Abels (1992)]]; [[#UBBAR15|Rigg (1992)]].</ref> ''Ubbe Ragnarsson'',<ref>[[#UBBAP20|Parker, EC (2012)]]; [[#UBBAF7|Fornasini (2009)]].</ref> ''Ubbe'',<ref>[[#UBBAB1|Barrow (2016)]]; [[#UBBAG20|Gore (2016)]]; [[#UBBAP8|Parker, E (2016)]]; [[#UBBAR18|Roffey; Lavelle (2016)]]; [[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]]; [[#UBBAP10|Parker, E (2014)]]; [[#UBBAR8|Reimer (2014)]]; [[#UBBAA7|Abels (2013)]]; [[#UBBAI2|IJssennagger (2013)]]; [[#UBBAP20|Parker, EC (2012)]]; [[#UBBAG17|Gigov (2011)]]; [[#UBBAC6|Cubitt (2009)]]; [[#UBBAF7|Fornasini (2009)]]; [[#UBBAR10|Rowe, EA (2008)]]; [[#UBBAC7|Cubitt; Costambeys (2004)]]; [[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]]; [[#UBBAK7|Kleinman (2004)]]; [[#UBBAS17|Smyth (2002)]]; [[#UBBAS27|Smyth (1998)]]; [[#UBBAF8|Frankis (1996)]]; [[#UBBAY2|Yorke (1995)]].</ref> ''Ubbi'',<ref>[[#UBBAS15|Somerville; McDonald (2014)]]; [[#UBBAW18|Emons-Nijenhuis (2013)]]; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]]; [[#UBBAF4|Finlay (2009)]]; [[#UBBAL8|Levy (2004)]]; [[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]]; [[#UBBAD4|Davidson; Fisher (1999)]]; [[#UBBAS26|Swanton, MJ (1999)]]; [[#UBBAR7|Rowe, E (1993)]].</ref> ''Ubbo'',<ref>[[#UBBAM8|McTurk, R (2015)]]; [[#UBBAI2|IJssennagger (2013)]]; [[#UBBAR10|Rowe, EA (2008)]]; [[#UBBAM13|McTurk, R (2006)]].</ref> and ''Ube''.<ref>[[#UBBAM8|McTurk, R (2015)]]; [[#UBBAM1|McTurk, R (2007)]].</ref>|group=note}} The Great Army appears to have been a coalition of warbands drawn from [[Scandinavia]], [[Ireland]], the [[Irish Sea]] region, and [[the Continent]]. There is reason to suspect that a proportion of the Viking forces specifically originated in [[Frisia]], where some Viking commanders are known to have held [[fiefdom]]s on behalf of the [[Franks]]. Some sources describe Ubba as ''{{lang|la|[[dux]]}}'' of the [[Frisian people|Frisians]], which could be evidence that he also associated with a Frisian benefice. |

|||

Contemporary English sources tend to describe the army's men as [[Danish people|Danes]] and heathens, but there is evidence to suggest that a proportion of the force originated in [[Frisia]], and one source describes Ubba as ''[[dux]]'' of the [[Frisian people|Frisians]]. In 865 the Great Army, apparently led by a man named [[Ivar the Boneless|Ivar]], overwintered in East Anglia, before invading and destroying the kingdom of Northumbria. In 869, having been bought off by the Mercians, the Vikings conquered the East Angles, and in the process killed their king, [[Edmund the Martyr|Edmund]], who was later regarded as a [[saint]] and [[Christian martyrs|martyr]]. While near-contemporary sources do not associate Ubba with the latter campaign, some later, less reliable sources associate him with the king's martyrdom. Others associate Ubba and Edmund's martyrdom in traditions concerning the [[saga]]-character Ragnar Lothbrok. |

|||

In 865 the Great Army, apparently led by [[Ívarr inn beinlausi|Ívarr]], overwintered in [[Kingdom of East Anglia]], before invading and destroying the [[Kingdom of Northumbria]]. In 869, having been bought off by the [[Mercians]], the Vikings conquered the East Angles, and in the process killed their king, [[Edmund the Martyr|Edmund]], a man who was later regarded as a [[saint]] and [[Christian martyrs|martyr]]. While near-contemporary sources do not specifically associate Ubba with the latter campaign, some later, less reliable sources associate him with the legend of Edmund's martyrdom. In time, Ívarr and Ubba came to be regarded as archetypal Viking invaders and opponents of [[Anglo-Saxon Christianity|Christianity]]. As such, Ubba features in several dubious [[hagiographical]] accounts of [[Anglo-Saxon saints]] and ecclesiastical sites. Non-contemporary sources also associate Ívarr and Ubba with the legend of [[Ragnarr loðbrók]], a figure of dubious historicity. Whilst there is reason to suspect that Edmund's cult was partly promoted to integrate Scandinavian settlers in Anglo-Saxon England, the legend of Ragnarr loðbrók may have originated in attempts to explain why they came to settle. |

|||

After the fall of the East Anglian kingdom, leadership of the Great Army appears to have fallen to [[Halfdan Ragnarsson|Halfdan]], Ivar's brother. The Vikings then campaigned against the West Saxons and destroyed the kingdom of the Mercians. In 873 the Great Army split in two: Halfdan led one part to campaign in the north before settling in Northumbria; the other part, under a leader named [[Guthrum]], campaigned against the West Saxons. In the winter of 877–78 Guthrum launched a lightning attack deep into Wessex, which may have been coordinated with a separate Viking force campaigning in [[Devon]]. According to a near-contemporary source, this force was led by a brother of Ivar and Halfdan, and some later sources identify him as Ubba. |

|||

After the fall of the East Anglian kingdom, leadership of the Great Army appears to have fallen to [[Bagsecg]] and [[Halfdan Ragnarsson|Hálfdan]], who campaigned against the Mercians and [[West Saxons]]. In 873 the Great Army is recorded to have split. Whilst Hálfdan settled his followers in Northumbria, the army under [[Guthrum]], Oscytel, and Anwend, struck out southwards, and campaigned against the West Saxons. In the winter of 877/878, Guthrum launched a lightning attack deep into Wessex. There is reason to suspect that this strike was coordinated with the campaigning of a separate Viking force in [[Devon]]. This latter army is reported to have been destroyed at [[Battle of Cynuit|''{{lang|la|Arx Cynuit}}'']] in 878. According to a near-contemporary source, this force was led by a brother of Ívarr and Hálfdan, and some later sources identify this man as Ubba himself. |

|||

==Origins and arrival of the Great Army== |

|||

[[File:Life of St. Edmund, Barbarians Invading England, c 1130.JPG|thumb|upright|Danish Vikings depicted in the twelfth-century ''MS M.736''.]] |

|||

In the mid-ninth century, an invading army descended on [[Anglo-Saxon England]]. The earliest version of the ''[[Anglo-Saxon Chronicle]]'', a near-contemporary source first compiled in the late-ninth century,<ref>[[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 217.</ref> calls this army "''micel here''",<ref>[[#M3|McLeod 2013]] p. 64 & n. 16; [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 68–69 (§ 866); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] p. 130 (§ 866).</ref>{{refn|Note that "§" in citations indicates a year or a section in a source; "§§" indicates two or more years or sections.|group=note}} an [[Old English]] term generally translated as "the [[Great Heathen Army|Great Army]]".<ref>[[#D4|Downham 2013a]] pp. 13–14; [[#M3|McLeod 2013]] p. 64.</ref>{{refn|The earliest form of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is the A-version. The Old English term ''micel hæðen here'', meaning "great heathen raiding-army", is accorded to the army in later versions (B, C, D, and E).<ref>[[#M3|McLeod 2013]] p. 64.</ref>|group=note}} The exact origins of this force are obscure, although the ''Chronicle'' usually identifies its members as [[Danish people|Danes]] or heathens.<ref>[[#D4|Downham 2013a]] p. 13.</ref><ref>[[#M3|McLeod 2013]] p. 64; [[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 71.</ref> The tenth-century churchman [[Asser]] stated in [[Latin]] that the invaders came "''de Danubia''", which translates into English as "from the [[Danube]]".<ref>[[#D4|Downham 2013a]] p. 13; [[#D5|Downham 2013b]] p. 53; [[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 64; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 98 (§ 24); [[#C5|Cook 1906]] p. 13 (§ 21); [[#G2|Giles 1906]] p. 50; [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] pp. 18–19 (§ 21); [[#S11|Stevenson 1854]] p. 449.</ref> Since the Danube is located in what was known in Latin as ''[[Dacia]]'', Asser probably intended ''Dania'', a Latin term for [[Denmark]].<ref>[[#D4|Downham 2013a]] p. 13; [[#D5|Downham 2013b]] p. 53; [[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 64.</ref> The tenth-century chronicler [[Æthelweard (historian)|Æthelweard]] (d. [[Circa|c.]] 998), in his ''[[Chronicon Æthelweardi]]'', reported that "the fleets of the tyrant [Ivar] arrived in the land of the English from the north",<ref name=Chronicon>[[#D4|Downham 2013a]] p. 13 & n. 23; [[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 64; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 156 (§ 1); [[#G2|Giles 1906]] p. 25; [[#S11|Stevenson 1854]] p. 427 (§ 866).</ref> implying a [[Scandinavia]]n origin.<ref name=Chronicon />{{refn|In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries Ivar came to be remembered in Scandinavian tradition as "Ivar the Boneless".<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] pp. 6 & 15; [[#W8|Woolf 2004]] p. 95.</ref>|group=note}} |

|||

==The origins of Ubba and the Great Army== |

|||

The Great Army may have included Vikings already active in England, as well as men directly from Scandinavia, [[History of Ireland (800–1169)|Ireland]] and the Continent:<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] pp. 63–65; [[#M3|McLeod 2013]] p. 76 & n. 67; [[#K1|Keynes 2001]] p. 54; [[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 71.</ref> a proportion of the army probably originated in [[Frisia]].<ref>[[#M3|McLeod 2013]] p. 84; [[#W3|Woolf 2007]] pp. 71–72; [[#W8|Woolf 2004]] p. 95; [[#B2|Bremmer 1981]].</ref> The ninth-century ''[[Annales Bertiniani]]'' records that Danish Vikings devastated Frisia in 851,<ref name="Rech 2014">[[#R1|Rech 2014]].</ref><ref>[[#W3|Woolf 2007]] pp. 71–72; [[#N1|Nelson 1991]] p. 73; [[#W5|Waitz 1883]] p. 41.</ref> and the twelfth-century ''[[Annales Lindisfarnenses et Dunelmenses]]'' states that a Viking force of Danes and [[Frisian people|Frisians]] made landfall on the [[Isle of Sheppey]] in 855.<ref>[[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 259</ref><ref>[[#S14|Stancliffe 1989]] pp. 28–29.</ref><ref>[[#V1|van Houts 1984]] p. 116; [[#B2|Bremmer 1981]] pp. 75–76; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] pp. 223, n. 25, 227; [[#P2|Pertz 1866]] p. 506.</ref> The same source, and the tenth- or eleventh-century ''[[Historia de Sancto Cuthberto]]'', describe Ubba – who is associated with Ivar in other sources – as ''[[dux]]'' of the Frisians.<ref>[[#D2|Davidson 1998]] (vol. 2), p. 156, n. 38; [[#V1|van Houts 1984]] p. 116; [[#B2|Bremmer 1981]] p. 76; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] pp. 223 n. 25 & 227; [[#P2|Pertz 1866]] p. 506.</ref><ref>[[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 359; [[#S6|South 2002]] p. 2.</ref><ref>[[#W3|Woolf 2007]] pp. 71–72; [[#S6|South 2002]] pp. 50–51 (§ 10) & 52–53 (§ 14); [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 227; [[#A2|Arnold 1882]] pp. 201–202 (§ 10) & 204 (§ 14); [[#H3|Hodgson Hinde 1868]] pp. 142 & 144.</ref>{{refn|''Annales Bertiniani'' is a [[West Francia|West Frankish]] source.<ref name="Rech 2014"/> At least one of the scribes who wrote ''Annales Lindisfarnenses et Dunelmenses'' was Symeon of Durham.<ref>[[#D6|Dunphy 2014]].</ref> ''Historia de Sancto Cuthberto'' was composed in northern Anglo-Saxon England.<ref>[[#K5|Kennedy 2014]].</ref>|group=note}} Furthermore, while the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' calls the Viking army ''micel here'', the Latin ''Historia de Sancto Cuthberto'' instead uses the term ''Scaldingi'', possibly meaning "people from the [[Scheldt|River Scheldt]]".<ref>[[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 72; [[#W8|Woolf 2004]] p. 95; [[#F1|Frank 2000]] p. 159.</ref>{{refn|Elsewhere in ''Historia de Sancto Cuthberto'', the term ''Scald'' is used to refer to the same river.<ref>[[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 72; [[#W8|Woolf 2004]] p. 95.</ref> Other possible meanings of ''Scaldingi'' include "shieldmen", "descendant of Scyld", and "men of the [[Punt (boat)|punt]]ed ship".<ref>[[#F1|Frank 2000]] pp. 159 & 117 n. 17.</ref>|group=note}} This suggests that Ubba may have been from [[Walcheren]], an island in the [[River mouth|mouth]] of the Scheldt.<ref name="W3=72">[[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 72.</ref> The island is known to have been occupied by Danish Vikings over two decades before, when the [[List of Frankish kings|Frankish emperor]] [[Lothair I]] (d. 855) granted the island to a certain Danish royal dynast named Harald in 841.<ref>[[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 72; [[#B7|Besteman 2004]] p. 105; [[#N2|Nelson 2001]] pp. 25 & 41; [[#N1|Nelson 1991]] p. 73; [[#L1|Lund 1989]] pp. 47 & 49 n. 16.</ref> If Ubba's troops were drawn from the Frisian settlement started by Harald over two decades before, many of Ubba's men might well have been born in Frisia.<ref name="W3=72"/> The considerable time that members of the Great Army appear to have spent in Ireland and the Continent suggests that these men were well accustomed to [[Germanic Christianity|Christian society]],<ref>[[#M3|McLeod 2013]] pp. 83–84; [[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 72.</ref> which in turn may partly explain their achievements in England.<ref name="W3=72"/> |

|||

[[File:Ubba (map).png|thumb|right|alt=Map of Britain, Ireland, and the Continent|Locations associated with Ubba's career.]] |

|||

==The Great Army under Ivar== |

|||

[[File:Harley MS 2278, folio 48r excerpt.jpg|thumb|left|Excerpt from ''Harley MS 2278'' depicting Hyngwar and Vbba ravaging the countryside.<ref>[[#H5|Harley MS 2278]].</ref> Lydgate's imaginative hagiography presents supposed ninth-century events in a [[chivalric]] context.<ref>[[#F3|Frantzen 2004]] pp. 66–70.</ref> ]] |

|||

In the autumn of 865, the ''Anglo Saxon Chronicle'' records that the Great Army invaded [[Kingdom of East Anglia|East Anglia]] and overwintered there.<ref>[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 69; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 48 (§ 866); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] pp. 57–58 (§ 866); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 68-69 (§ 866); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 196 (§ 866); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 140 (§ 866); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 49 (§ 866); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 58 (§ 866); [[#H4|Hervey 1907]] pp. 2–3 (§ 866); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 68–69 (§ 866); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 130–131; [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 59 (§ 866); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 43 (§ 866); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 97 (§ 866).</ref> That winter the Vikings evidently gained valuable intelligence, and the ''Chronicle'' states that, the following spring, they left East Anglia on horses gained from the subordinated population and struck deep into the [[Kingdom of Northumbria|kingdom of the Northumbrians]], which was in the midst of a civil war between the rival kings [[Ælla of Northumbria|Ælla]] (d. 867) and [[Osberht of Northumbria|Osberht]] (d. 867).<ref>[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] pp. 69–70; [[#K3|Kirby 2002]] p. 173; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 48 (§ 867); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 58 (§ 867); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 68–69 (§ 867); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 196 (§ 867); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 140 (§ 867); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 49 (§ 867); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 58 (§ 867); [[#H4|Hervey 1907]] pp. 2–3 (§ 867); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 68–69 (§ 867); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 130–133; [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 59 (§ 867); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 43 (§ 867); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] pp. 97–98 (§ 867).</ref> |

|||

In the mid ninth century, an invading [[Viking]] army coalesced in [[Anglo-Saxon England]]. The earliest version of the ninth- to twelfth-century ''[[Anglo-Saxon Chronicle]]'' variously describes the invading host as "''{{lang|ang|micel here}}''",<ref>[[#UBBAD2|Downham (2013a)]] p. 13; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 9, 27 n. 96; [[#UBBAS14|Sheldon (2011)]] p. 12, 12 n. 13; [[#UBBAM7|McLeod, S (2013)]] p. 64, 64 n. 16; [[#UBBAS6|Swanton, M (1998)]] p. 68 § 866; [[#UBBAG6|Gomme (1909)]] p. 58 § 866; [[#UBBAH4|Hervey (1907)]] pp. 2–3 § 866; [[#UBBAP4|Plummer; Earle (1892)]] p. 68 § 866; [[#UBBAT4|Thorpe (1861a)]] p. 130 § 866; [[#UBBAT5|Thorpe (1861b)]] p. 59 § 866.</ref> an [[Old English]] term that can translate as "big army"<ref>[[#UBBAD2|Downham (2013a)]] p. 14; [[#UBBAD7|Downham (2013b)]] p. 52; [[#UBBAD8|Downham (2012)]] p. 4; [[#UBBAS14|Sheldon (2011)]] p. 12.</ref> or "great army".<ref>[[#UBBAS15|Somerville; McDonald (2014)]] p. 230; [[#UBBAD2|Downham (2013a)]] p. 14; [[#UBBAD7|Downham (2013b)]] p. 52; [[#UBBAM7|McLeod, S (2013)]] p. 64; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 9, 27 n. 96; [[#UBBAH8|Halsall (2007)]] p. 106; [[#UBBAW8|Williams, A (1999)]] p. 69.</ref>{{#tag:ref|The earliest form of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is the ninth- or tenth-century "A" version. Forms of the Old English term "''{{lang|ang|mycel hæðen here}}''", meaning "great heathen raiding-army", are accorded to the army in later versions.<ref>[[#UBBAS15|Somerville; McDonald (2014)]] p. 231 § 866; [[#UBBAM7|McLeod, S (2013)]] p. 64; [[#UBBAS14|Sheldon (2011)]] p. 12, 12 n. 13; [[#UBBAI1|Irvine (2004)]] p. 48 § 866; [[#UBBAO1|O'Keeffe (2001)]] p. 58 § 867; [[#UBBAS6|Swanton, M (1998)]] p. 69 § 866; [[#UBBAW4|Whitelock (1996)]] p. 196 § 866; [[#UBBAT6|Taylor (1983)]] p. 34 § 867; [[#UBBAC4|Conybeare (1914)]] p. 140 § 866; [[#UBBAG7|Giles (1914)]] p. 49 § 866; [[#UBBAH4|Hervey (1907)]] pp. 2–3 § 866; [[#UBBAG8|Giles (1903)]] p. 351 § 866; [[#UBBAP4|Plummer; Earle (1892)]] p. 69 § 866, 69 n. 3; [[#UBBAT4|Thorpe (1861a)]] pp. 130–131 § 866/867; [[#UBBAT5|Thorpe (1861b)]] p. 59 § 866; [[#UBBAS10|Stevenson, J (1853)]] p. 43 § 866.</ref>|group=note}} [[Archaeological]] evidence and documentary sources suggest that this [[Great Army (Viking)|Great Army]] was not a single unified force, but more of a composite collection of warbands drawn from different regions.<ref>[[#UBBAH9|Hadley; Richards; Brown et al. (2016)]] p. 55; [[#UBBAM7|McLeod, S (2013)]] pp. 75–76, 79 n. 77; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 10, 81–82, 113, 119–120; [[#UBBAB12|Budd; Millard; Chenery et al. (2004)]] pp. 137–138.</ref> |

|||

Late in 866 the Vikings seized [[History of York|York]],<ref name="asc-york">[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 65; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] pp. 69–70; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 48 (§ 867); [[#K1|Keynes 2001]] p. 54; [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 58 (§ 867); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 68–69 (§ 867); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 196 (§ 867); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 140 (§ 867); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 49 (§ 867); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 58 (§ 867); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 68–69 (§ 867); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 130–133; [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 59 (§ 867); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 43 (§ 868); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] pp. 97–98 (§ 867).</ref>{{refn|The taking of York is dated to 1 November, the [[All Saints' Day|Feast of All Saints]], by ''[[Libellus de exordio|Libellus de exordio atque procursu istius hoc est Dunhelmensis ecclesie]]'',<ref>[[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 196 n. 7; [[#S13|Stevenson 1855]] p. 654.</ref> a twelfth-century source often attributed to the churchman [[Symeon of Durham]] (d. c. 1128),<ref>[[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 359; [[#G7|Gransden 1996]] pp. 115–116.</ref> and the thirteenth-century ''[[Flores Historiarum]]'', by the churchman [[Roger of Wendover]] (d. 1236).<ref>[[#S5|Smyth 1977]] p. 181; [[#C7|Coxe 1841]] pp. 298–299 (§ 867); [[#G6|Giles 1849]] pp. 189–190 (§ 867).</ref> Attacking a populated site on a [[feast day]] was a noted tactic of the Vikings. Such celebrations offered attackers easy access to potential captives who could be ransomed or sold into slavery.<ref>[[#N2|Nelson 2001]] p. 38; [[#S5|Smyth 1977]] p. 181.</ref>|group=note}} one of only two [[Archbishop|archiepiscopal]] [[Episcopal see|sees]] in England and one of the richest trading centres in Britain.<ref name="F2=70">[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 70.</ref> Although Ælla and Osberht responded by joining forces against the Vikings, the ''Chronicle'' indicates that their attack on York was a disaster and they both died.<ref name="asc-york"/> With the collapse of the kingdom and destruction of its regime, the twelfth-century ''[[Historia Regum]]'' reveals that the Vikings installed [[Ecgberht I of Northumbria|Ecgberht]] (d. 873) as a Northumbrian [[puppet king]].<ref name="historiaregum">[[#T2|Timofeeva 2011]] p. 119; [[#S6|South 2002]] p. 10; [[#G7|Gransden 1996]] pp. 148–149.</ref><ref>[[#K2|Keynes 2014]] p. 526; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 70; [[#S7|Sawyer 2001]] p. 275; [[#A3|Arnold 1885]] pp. 105–106.</ref>{{refn|Although one manuscript of ''Historia Regum'' attributes its composition to Symeon, this identification is debatable.<ref name="historiaregum"/>|group=note}} |

|||

The exact origins of the Great Army are obscure.<ref>[[#UBBAD2|Downham (2013a)]] p. 13; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 71.</ref> The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' sometimes identifies the Vikings as [[Danish people|Danes]].<ref>[[#UBBAM7|McLeod, S (2013)]] p. 64; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 10, 12–13, 120–121; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 71.</ref> The tenth-century ''[[Vita Alfredi]]'' seems to allege that the invaders came from [[Denmark]].<ref>[[#UBBAD2|Downham (2013a)]] p. 13; [[#UBBAD7|Downham (2013b)]] p. 53; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 140; [[#UBBAD3|Downham (2007)]] p. 64; [[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. asser's life of king alfred § 21, asser's life of king alfred § 21 n. 44; [[#UBBAS17|Smyth (2002)]] pp. 13 ch. 21, 183, 217–218 n. 61, 224 n. 139; [[#UBBAC4|Conybeare (1914)]] p. 98 § 24 ch. 21; [[#UBBAC5|Cook (1906)]] p. 13 ch. 21; [[#UBBAG9|Giles (1906)]] p. 50; [[#UBBAS8|Stevenson, WH (1904)]] p. 19 ch. 21; [[#UBBAS9|Stevenson, J (1854)]] p. 449, 449 n. 6.</ref> A [[Scandinavia]]n origin may be evinced by the tenth-century ''Chronicon Æthelweardi'', which states that "the fleets of the tyrant Ívarr" arrived in Anglo-Saxon England from "the north".<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] p. 18; [[#UBBAD2|Downham (2013a)]] p. 13, 13 n. 23; [[#UBBAD3|Downham (2007)]] p. 64; [[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. asser's life of king alfred § 21 n. 44; [[#UBBAK1|Kirby (2002)]] p. 173; [[#UBBAS6|Swanton, M (1998)]] p. 68 n. 5; [[#UBBAW4|Whitelock (1996)]] p. 196 n. 5; [[#UBBAO3|Ó Corráin (1979)]] pp. 314–315; [[#UBBAM5|McTurk, RW (1976)]] pp. 117 n. 173, 119; [[#UBBAS7|Stenton (1963)]] p. 244 n. 2; [[#UBBAC4|Conybeare (1914)]] p. 156 bk. 4 ch. 2 § 1; [[#UBBAG9|Giles (1906)]] p. 25 bk. 4 ch. 2; [[#UBBAT8|''The Whole Works of King Alfred the Great'' (1858)]] p. 30; [[#UBBAS9|Stevenson, J (1854)]] p. 427 bk. 4 ch. 2.</ref> With the turn of the mid-ninth century, this [[Ívarr inn beinlausi|Ívarr]] (died 869/870?)<ref>[[#UBBAG20|Gore (2016)]] pp. 62, 68 n. 70; [[#UBBAD3|Downham (2007)]] p. 64; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 73; [[#UBBAC17|Costambeys (2004b)]]; [[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. asser's life of king alfred § 21 n. 44.</ref> was one of the foremost Viking leaders in [[Great Britain|Britain]] and [[Ireland]].<ref>[[#UBBAD3|Downham (2007)]] p. 67; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] pp. 71–73.</ref> |

|||

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' records that the Great Army attacked [[Mercia]] in 867, after which the Vikings seized [[Nottingham]] and overwintered there.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 65; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] pp. 70–71; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 48 (§ 868); [[#K1|Keynes 2001]] p. 54; [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 58 (§ 868); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 68–71 (§ 868); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 197 (§ 868); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 140 (§ 868); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] pp. 49–50 (§ 868); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp. 58–59 (§ 868); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 68–71 (§ 868); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 132–135; [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 59 (§ 868); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 43 (§ 868); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 98 (§ 868).</ref> Although the respective Mercian and West Saxon kings [[Burgred of Mercia|Burgred]] (d. [[Circa|c.]] 874) and [[Æthelred of Wessex|Æthelred]] (d. 871) responded by joining forces and besieging the occupied town, both the ''Chronicle'' and Asser record that this combined Anglo-Saxon force was unable to dislodge the army.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 65; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] pp. 70–72; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 48 (§ 868); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 58 (§ 868); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 68–71 (§ 868); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 197 (§ 868); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 140 (§ 868); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] pp. 49–50 (§ 868); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp. 58–59 (§ 868); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 68–71 (§ 868); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 132–135 [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 59 (§ 868); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 43 (§ 868); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 98 (§ 868).</ref><ref>[[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 70–71 & n. 1; [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 197 n. 2; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] pp. 101–102 (§ 30); [[#C5|Cook 1906]] pp. 17–18 (§ 30); [[#G2|Giles 1906]] p. 53; [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] pp. 24–25 (§ 30); [[#S11|Stevenson 1854]] p. 452.</ref> In the meantime the Great Army renewed its strength for future forays, and the ''Chronicle'' records that it was only through a haggled truce that the Mercians were able to induce the Vikings to withdraw to York.<ref name="F2=70"/><ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 65; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 72; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 48 (§ 869); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 58 (§ 869); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] p. 71 (§ 869); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 197 (§ 869); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 140 (§ 869); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 50 (§ 869); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 59 (§ 869); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 70–71 (§ 869); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 134–135; [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 60 (§ 869); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 43 (§ 869); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 99 (§ 869).</ref> |

|||

[[File:Viking invasion (Pierpont Morgan Library MS M.736, folio 9v) crop.jpg|upright|thumb|left|A twelfth-century depiction of the invading [[Vikings]] on folio 9v of Pierpont Morgan Library M.736.<ref>[[#UBBAW9|Williams, G (2017)]] p. 31; [[#UBBAP19|Pinner (2010)]] pp. 99, 100 fig. 7; [[#UBBAT7|''The Life and Miracles of St. Edmund'' (n.d.)]].</ref>{{#tag:ref|The thirty-two painted [[Miniature (illuminated manuscript)|miniatures]] that make up this manuscript are scenes from ''Passio sancti Eadmundi'' and ''De miraculis sancti Eadmundi''.<ref>[[#UBBAP19|Pinner (2010)]] p. 98.</ref>|group=note}}]] |

|||

==Martyrdom of Edmund== |

|||

[[File:12th-century painters - Life of St Edmund - WGA15723.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Edmund the Martyr|Edmund]]'s martyrdom, depicted in the twelfth-century ''MS M.736''.{{refn|This [[Miniature (illuminated manuscript)|miniature]] is one of several in the manuscript's [[Illuminated manuscript|illuminated]] copy of Abbo's ''Passio Sancti Eadmundi''. The manuscript is held in [[Pierpont Morgan Library]], New York.<ref>[[#M4|Mills 2013]] p. 38; [[#B1|Bale 2009]] pp. 9, 63 & 188.</ref>|group=note}} ]] |

|||

The Great Army may have included Vikings already active in Anglo-Saxon England, as well as men directly from Scandinavia, Ireland, the [[Irish Sea]] region, and [[the Continent]].<ref>[[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] pp. 137–138; [[#UBBAM7|McLeod, S (2013)]] pp. 76, 76 n. 67, 83–84, 84 nn. 94–95; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 28, 119–180 ch. 3, 273, 285; [[#UBBAD3|Downham (2007)]] pp. 64–65; [[#UBBAK2|Keynes (2001)]] p. 54; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 71; [[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. asser's life of king alfred § 21 n. 44.</ref> There is reason to suspect that a proportion of the army specifically originated in [[Frisia]].<ref>[[#UBBAK11|Knol; IJssennagger (2017)]] p. 20; [[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] pp. 137–139; [[#UBBAI2|IJssennagger (2013)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAM7|McLeod, S (2013)]] pp. 76 n. 67, 83–84, 84 n. 95; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 28, 119–180 ch. 3; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] pp. 71–72; [[#UBBAW6|Woolf (2004)]] p. 95; [[#UBBAS27|Smyth (1998)]] pp. 24–25; [[#UBBAB7|Bremmer, RH (1981)]].</ref> For example, the ninth-century ''[[Annales Bertiniani]]'' reveals that Danish Vikings devastated Frisia in 850,<ref>[[#UBBAS15|Somerville; McDonald (2014)]] p. 210 § 850; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] pp. 71–72; [[#UBBAN2|Nelson (1991)]] p. 69 § 850; [[#UBBAW7|Waitz (1883)]] p. 38 § 850; [[#UBBAP6|Pertz (1826)]] p. 445 § 850.</ref> and the twelfth-century ''Annales Lindisfarnenses et Dunelmenses'' states that a Viking force of Danes and [[Frisian people|Frisians]] made landfall on the [[Isle of Sheppey]] in 855.<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] p. 20; [[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] pp. 137, 137 n. 8, 137–138; [[#UBBAI2|IJssennagger (2013)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAB17|Bremmer, R (1984)]] p. 359; [[#UBBAV3|van Houts (1984)]] p. 116, 116 n. 56; [[#UBBAB7|Bremmer, RH (1981)]] pp. 76–77; [[#UBBAW2|Whitelock (1969)]] pp. 223 n. 26, 227; [[#UBBAM9|Mawer (1908–1909)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAP7|Pertz (1866)]] p. 506 § 855.</ref>{{#tag:ref|The Viking commanders specifically associated with this event are Ubba, [[Halfdan Ragnarsson|Hálfdan]] (died 877), and Ívarr.<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] p. 20; [[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] pp. 137, 137 n. 8, 137–138; [[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]] p. 60; [[#UBBAB17|Bremmer, R (1984)]] p. 359; [[#UBBAV3|van Houts (1984)]] p. 116, 116 n. 56; [[#UBBAO3|Ó Corráin (1979)]] pp. 316–317; [[#UBBAM5|McTurk, RW (1976)]] pp. 96 n. 22, 113, 113 n. 148, 119; [[#UBBAM9|Mawer (1908–1909)]] pp. 80, 83, 85; [[#UBBAP7|Pertz (1866)]] p. 506 § 855.</ref>|group=note}} The same source,<ref>[[#UBBAI2|IJssennagger (2013)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]] pp. 60–61; [[#UBBAD4|Davidson; Fisher (1999)]] vol. 2 p. 156 n. 38; [[#UBBAB17|Bremmer, R (1984)]] p. 359; [[#UBBAV3|van Houts (1984)]] p. 116, 116 n. 56; [[#UBBAB7|Bremmer, RH (1981)]] pp. 76–77; [[#UBBAO3|Ó Corráin (1979)]] pp. 316–317; [[#UBBAC14|Cox (1971)]] p. 51 n. 19; [[#UBBAW2|Whitelock (1969)]] pp. 223 n. 26, 227; [[#UBBAM9|Mawer (1908–1909)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAP7|Pertz (1866)]] p. 506 § 868.</ref> and the tenth- or eleventh-century ''[[Historia de sancto Cuthberto]]'', describe Ubba as ''{{lang|la|[[dux]]}}'' of the Frisians.<ref>[[#UBBAB1|Barrow (2016)]] p. 85; [[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] pp. 18–20; [[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] p. 137; [[#UBBAM15|McGuigan (2015)]] p. 21; [[#UBBAM8|McTurk, R (2015)]] p. 106; [[#UBBAI2|IJssennagger (2013)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 141, 141 n. 156; [[#UBBAG12|Gazzoli (2010)]] p. 36, 36 n. 71; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] pp. 71–72; [[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]] pp. 59, 61; [[#UBBAS12|South (2002)]] pp. 50–51 ch. 10, 52–53 ch. 14; [[#UBBAJ4|Johnson-South (1991)]] p. 623; [[#UBBAB17|Bremmer, R (1984)]] pp. 359–360, 366 n. 12; [[#UBBAV3|van Houts (1984)]] p. 116, 116 n. 55; [[#UBBAM5|McTurk, RW (1976)]] pp. 104 n. 86, 120 n. 199; [[#UBBAC14|Cox (1971)]] p. 51 n. 19; [[#UBBAW2|Whitelock (1969)]] p. 227; [[#UBBAM9|Mawer (1908–1909)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAA3|Arnold (1882)]] pp. 201–202 bk. 2 ch. 10, 204 bk. 2 ch. 14; [[#UBBAH7|Hodgson Hinde (1868)]] pp. 142, 144.</ref>{{#tag:ref|The thirteenth-century ''[[Gesta Danorum]]'' makes reference to Ubbo Fresicus, a figure stated to have assisted [[Haraldr hilditǫnn]] against the forces of Hringr in the legendary [[Battle of Brávellir]].<ref>[[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] p. 137; [[#UBBAM8|McTurk, R (2015)]] p. 106; [[#UBBAI2|IJssennagger (2013)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 145, 145 n. 177; [[#UBBAD4|Davidson; Fisher (1999)]] vol. 1 p. 242 bk. 8, vol. 2 p. 156 n. 38; [[#UBBAM9|Mawer (1908–1909)]] pp. 84–85; [[#UBBAH12|Holder (1886)]] pp. 262–263 bk. 8; [[#UBBAE3|Elton; Powell; Anderson; Buel (n.d.)]] p. 480 bk. 8.</ref> A similarly named Ubbi fríski is attested by the thirteenth-century ''[[Sǫgubrot af nokkrum fornkonungum]]''.<ref>[[#UBBAM8|McTurk, R (2015)]] p. 106; [[#UBBAR4|Rafn (1829)]] pp. 379–383 chs. 8–9.</ref> The character these figures represent may well be moddled after Ubba, also associated with Frisia and the Frisians.<ref>[[#UBBAM8|McTurk, R (2015)]] pp. 106–107.</ref>|group=note}} |

|||

In 869 the kingdom of East Anglia fell to the Great Army. The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle''{{'}}s account of the conflict reveals that the Vikings took up winter quarters at [[Thetford]], where they fought and destroyed the East Anglian army and killed King [[Edmund the Martyr|Edmund]].<ref>[[#M5|Mostert 2014]] pp. 165–166; [[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 64; [[#W1|Winstead 2007]] p. 128; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 48 (§ 870); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 58 (§ 871); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 70–71 (§ 870); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 197 & n. 6 (§ 870); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] pp. 140-141 (§ 870); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] pp. 50–51 (§ 870); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp. 59–70 (§ 870); [[#H4|Hervey 1907]] pp. 2–3 (§ 870); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 70–71 (§ 870); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 134–136 (§ 870); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 60 (§ 870); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] pp. 43–44 (§ 870); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 99 (§ 870).</ref> Although the ''Chronicle'''s account of the conflict suggests that Edmund was slain in battle,<ref>[[#M5|Mostert 2014]] pp. 165–166; [[#G1|Gransden 2004]].</ref> and Asser certainly stated as much in his version of events,<ref>[[#G1|Gransden 2004]]; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 102 (§ 33); [[#H4|Hervey 1907]] pp. 4–5; [[#C5|Cook 1906]] p. 18 (§ 33); [[#G2|Giles 1906]] p. 26; [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] p. 26 (§ 33); [[#S11|Stevenson 1854]] p. 452 (§ 870).</ref> later [[hagiographical]] works portray the king in an idealised light, and depict his death in the context of a peace-loving Christian monarch, who willingly suffered [[Christian martyrs|martyrdom]] after refusing to shed blood in defence of himself.<ref>[[#M5|Mostert 2014]] pp. 165–166; [[#W1|Winstead 2007]] p. 128; [[#F3|Frantzen 2004]] pp. 61–66; [[#G1|Gransden 2004]].</ref> One such account is the ''[[Edmund the Martyr#The Passio Sancti Eadmundi|Passio Sancti Eadmundi]]'', by the eleventh-century churchman [[Abbo of Fleury]]. Despite its obvious hagiographic embellishments, this source appears to be the latest useful source concerning Edmund's demise,<ref>[[#M5|Mostert 2014]] pp. 165–166; [[#D4|Downham 2013a]] p. 15; [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] pp. 119–120; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 233.</ref>{{refn|Abbo's account likens Edmund to [[Jesus Christ]] and [[Saint Sebastian|St Sebastian]]. Specifically, Edmund is mocked and [[scourged]] like Christ, and later tied to a tree and shot like St Sebastian.<ref>[[#M4|Mills 2013]] p. 37; [[#G1|Gransden 2004]]; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] pp. 219–220; [[#P6|Earle; Plummer 1965]] p. 86; [[#H4|Hervey 1907]] pp. 32–37 (§ 10); [[#A1|Arnold 1890]] pp. 15–16 (§ 10).</ref> Not long after Abbo wrote ''Passio Sancti Eadmundi'', the eleventh-century churchman [[Ælfric of Eynsham]] (d. c. 1010) composed an adapted form of it. Ælfric's version, however, does not offer any further historical details concerning Edmund's demise.<ref>[[#M5|Mostert 2014]] pp. 165–166; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 222.</ref> Abbo wrote his account at least one hundred and sixteen years after Edmund's death. Abbo claimed that his account—except for the final miracle—was derived from a tale that he had heard told by the elderly [[Dunstan|Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury]] (d. 988) tell the tale. According to Abbo, Dunstan had heard this tale told, as a young man, from a very old man who claimed to have once been Edmund's armour-bearer.<ref>[[#M4|Mills 2013]] p. 37; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] pp. 218–219; [[#P6|Earle; Plummer 1965]] p. 86.</ref>|group=note}} and its claim that Edmund was captured and executed is plausible.<ref>[[#M5|Mostert 2014]] pp. 165–166; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] pp. 221–222; [[#A1|Arnold 1890]] pp. 15–16 (§ 10).</ref> In regard to Ubba, Abbo's account states that Ivar left him in Northumbria before launching his assault upon the East Angles.<ref>[[#M8|Mostert 1987]] p. 42; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 219; [[#H4|Hervey 1907]] pp. 18–21 (§ 5); [[#A1|Arnold 1890]] pp. 8–10 (§ 5).</ref>{{refn|Abbo's account makes no mention of the Vikings' actions in East Anglia in 865, and implies erroneously that they arrived in Northumbria by sea.<ref>[[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] pp. 220–221.</ref>|group=note}} In contrast to this source, the early twelfth-century F-version of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' specifically identifies Ivar and Ubba as the commanders of the king's killers.<ref name="Whitelock 1969 p. 223">[[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 223.</ref><ref>[[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 70–71 & n. 2; [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 197 n. 6; [[#B2|Bremmer 1981]] p. 77; [[#M1|McTurk 1976]] p. 119; [[#S16|Stenton 1963]] p. 244 n. 2; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] pp. 140–141 (§ 870); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] pp. 50–51 (§ 870); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 59 n. 2; [[#H4|Hervey 1907]] pp. 2–3 (§ 870); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 134–136; [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 60 (§ 870); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 99 (§ 870).</ref> This could be a mistake on the chronicler's part,<ref name="Whitelock 1969 p. 223"/> and later, less reliable literature concerning Edmund's death also associates these two Vikings with it.{{refn|One such example is ''[[Estoire des Engleis]]'', by the twelfth-century chronicler [[Geoffrey Gaimar]]. Gaimar identifies Ivar and Ubba as prominent Viking commanders, stating that, after the defeat of Edmund and fall of his kingdom, Ivar and Ubba cruelly put the king to death.<ref>[[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] pp. 224–225; [[#H4|Hervey 1907]] pp. 122–133.</ref>|group=note}} |

|||

Whilst the Old English ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' calls the Viking army ''{{lang|ang|micel here}}'', the [[Latin]] ''Historia de sancto Cuthberto'' instead gives ''{{lang|la|Scaldingi}}'',<ref>[[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 141–142; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 72; [[#UBBAF6|Frank (2000)]] p. 159; [[#UBBAA8|Anderson, CE (1999)]] p. 125; [[#UBBAB26|Björkman (1911–1912)]] p. 132; [[#UBBAA3|Arnold (1882)]] pp. 200 ch. 7, 202 chs. 11–12; [[#UBBAH7|Hodgson Hinde (1868)]] pp. 141, 143; [[#UBBAB10|Bense (n.d.)]] pp. 2–3.</ref> a term of uncertain meaning that is employed three times in reference to the leadership of the Viking forces.<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] pp. 22–23.</ref> One possibility is that world could mean "people from the [[Scheldt|River Scheldt]]".<ref>[[#UBBAA6|Anderson, CE (2016)]] pp. 462 n. 5, 470 n. 22; [[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] pp. 22–23; [[#UBBAD5|de Rijke (2011)]] p. 67; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 142; [[#UBBAG12|Gazzoli (2010)]] p. 36; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 72; [[#UBBAB11|Besteman (2004)]] p. 105; [[#UBBAW6|Woolf (2004)]] p. 95; [[#UBBAF6|Frank (2000)]] p. 159; [[#UBBAV2|Van Heeringen (1998)]] p. 245; [[#UBBAB26|Björkman (1911–1912)]].</ref>{{#tag:ref|Elsewhere, this river is called ''{{lang|ang|Scald}}'' in [[Old English]], and called ''{{lang|la|Scaldis}}'' in Latin.<ref>[[#UBBAA6|Anderson, CE (2016)]] pp. 462 n. 5; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 142; [[#UBBAG12|Gazzoli (2010)]] p. 36; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 72; [[#UBBAW6|Woolf (2004)]] p. 95.</ref> Other possible meanings of ''{{lang|la|Scaldingi}}'' include: "shieldmen",<ref>[[#UBBAF6|Frank (2000)]] pp. 159, 173 n. 17.</ref> "descendant of ''{{lang|ang|Scyld}}''",<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] pp. 24–25; [[#UBBAF6|Frank (2000)]] pp. 159, 173 n. 17; [[#UBBAB26|Björkman (1911–1912)]].</ref> and "men of the [[Punt (boat)|punt]]ed ship".<ref>[[#UBBAA6|Anderson, CE (2016)]] p. 462 n. 5; [[#UBBAF6|Frank (2000)]] pp. 159, 173 n. 17; [[#UBBAB26|Björkman (1911–1912)]].</ref>|group=note}} This could indicate that Ubba was from [[Walcheren]], an island in the [[River mouth|mouth]] of the Scheldt.<ref>[[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 142; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 72.</ref> Walcheren is known to have been occupied by Danish Vikings over two decades before.<ref>[[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 142; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 72; [[#UBBAB11|Besteman (2004)]] p. 105; [[#UBBAN1|Nelson (2001)]] pp. 25, 41; [[#UBBAS13|Sawyer (2001)]] p. 274; [[#UBBAL4|Lund (1989)]] pp. 47, 49 n. 16.</ref> For example, ''Annales Bertiniani'' reports that [[Lothair I, King of Middle Francia]] (died 855) granted the island to a Viking named Herioldus in 841.<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] p. 7; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 143; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 72; [[#UBBAN2|Nelson (1991)]] p. 51; [[#UBBAL4|Lund (1989)]] pp. 47, 49 n. 16; [[#UBBAW7|Waitz (1883)]] p. 26 § 841; [[#UBBAP6|Pertz (1826)]] p. 438 § 841.</ref> |

|||

==The Great Army under Halfdan== |

|||

After Edmund's death and the destruction of the East Anglian kingdom, Ivar disappears from English sources altogether.<ref name="Forte p. 72">[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 72.</ref> In the second half of 870, one of the commanders of the Great Army was Ivar's brother [[Halfdan Ragnarsson|Halfdan]], who led it against the kingdom of [[Wessex]].<ref name="Forte p. 72"/> The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' reports that, having established itself at [[Reading, Berkshire|Reading]] in 871, the army fought nine battles against the West Saxons.<ref name="ninebattle">[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] pp. 72–73; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] pp. 48–49 (§ 871); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 58 (§ 871); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 70–73 (§ 871); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] pp. 197–198 (§ 871); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 141–142 (§ 871); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] pp. 51–52 (§ 871); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp. 60–61 (§ 871); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 70–73 (§ 871); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 136–143 (§ 871); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] pp. 61–62 (§ 871); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] pp. 44–45 (§ 871); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] pp. 99–101 (§ 871).</ref> The most important of these seems to have been an engagement early that year, somewhere on the [[Berkshire Downs]] at a place then known as [[Battle of Ashdown|Ashdown]].<ref>[[#C4|Costambeys 2004]].</ref> This particular conflict marks Halfdan's first appearance in documentary sources.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 68; [[#C4|Costambeys 2004]].</ref> Despite the particular savagery attributed to these engagements by the ''Chronicle'', the battles seem to have been indecisive, and the Vikings appear to have been taken aback by the West Saxons' stiff resistance.<ref>[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] pp. 72–73.</ref> In consequence, the ''Chronicle'' records that the Great Army accepted a truce from [[Alfred the Great|Alfred]], the newly crowned [[List of monarchs of Wessex|West Saxon king]].<ref name="ninebattle"/> |

|||

[[File:Ubbi fríski (AM 1 e beta I fol., folio 4v).jpg|thumb|right|alt=Refer to caption|The name of Ubbi fríski, a saga-character who may refer to Ubba,<ref name="UBBAM8-106">[[#UBBAM8|McTurk, R (2015)]] p. 106.</ref> as it appears on folio 4v of AM 1 e beta I fol (''[[Sǫgubrot af nokkrum fornkonungum]]'').<ref>[[#UBBAR4|Rafn (1829)]] p. 379 ch. 8; [[#UBBAA16|''AM 1 E Beta I Fol'' (n.d.)]].</ref>]] |

|||

On the conclusion of the truce, the ''Chronicle'' reports that the Vikings withdrew to London and overwintered there.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 68; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 49 (§ 872); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] pp. 58–59 (§ 872); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 71–72 (§ 872); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 199 (§ 872); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 142 (§ 872); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 52 (§ 872); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 61 (§ 872); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 72–73 (§ 872); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 142–;143 (§ 872); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 62 (§ 872); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 45 (§ 872); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] pp. 101–102 (§ 872).</ref> They probably gained control of London as, about a decade later, most versions of the ''Chronicle'' appear to indicate that Alfred recovered it from Viking occupation.<ref>[[#A6|Abels 2013]] p. 171 & n. 4; [[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 68; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 51 (§ 883); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 69 (§ 884); [[#K4|Keynes 1998]] pp. 12–13 & n. 49, 21–23; [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] p. 79 & n. 20 (§ 883); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 202 (§ 883); [[#B5|Brooke; Keir 1975]] p. 19 & n. 2; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] pp. 144–145 (§ 883); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 55 (§ 883); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp. 64–65 (§ 883); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] p. 79 (§ 883); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 150–153 (§ 883); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 66 (§ 88); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] pp. 47–48 (§ 883); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 107 (§ 883).</ref>{{refn|Only the A-version of this source fails to refer to this event.<ref>[[#K4|Keynes 1998]] p. 21; [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] p. 79 n. 20; [[#B5|Brooke; Keir 1975]] p. 19 n. 2.</ref>|group=note}} In 873, some versions of the ''Chronicle'' report that the army marched north into Northumbria,<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] pp. 68–69; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 73; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 49 (§ 873); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 60 (§ 874); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] p. 72 (§ 873); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 199 (§ 873); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 142 (§ 873); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 522 (§ 873); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 61 (§ 873); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 72–73 (§ 873); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 142–143; [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 62 (§ 873); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 45 (§ 873); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 102 (§ 873).</ref> a relocation perhaps undertaken in the context of suppressing a revolt against their Northumbrian puppet king.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] pp. 68–69; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 73.</ref>{{refn|This move into Northumbria is omitted in the D- and E-versions of the ''Chronicle'',<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 69 n. 32; [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] p. 73 (§ 873); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 199 (§ 873), 199 n. 1; [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 142–143; [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 62 n. 2.</ref> and is not mentioned by Æthelweard.<ref>[[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 199 & n. 1 (§ 873).</ref>|group=note}} On the other hand, the relocation may have been part of a campaign in northern Mercia.<ref name="Downham 2007 p. 69">[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 69.</ref> The ''Chronicle'' indicates that the Vikings overwintered at [[Torksey]] in 873, after which they forced Burgred from the Mercian throne and installed [[Ceolwulf II of Mercia|Ceolwulf]], probably a descendant of King [[Ceolwulf I of Mercia]] (821–23), as a puppet king in his place.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 69; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] pp. 73–74; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] pp. 49–50 (§§ 873, 874); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 60 (§§ 873, 874); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 72–73 (§§ 873, 874); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 199 (§§ 873, 874); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 142 (§§ 873, 874); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] pp. 52–53 (§§ 873, 874); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp. 61–62 (§§ 873, 874); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 72–73 (§§ 873, 874); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 142–143 (§§ 873, 874); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] pp. 62–63 (§§ 873, 874); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 45 (§§ 873, 874); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 102 (§§ 873, 874).</ref> |

|||

According to the same source and the ninth-century ''[[Annales Fuldenses]]'', another Viking named [[Roricus of Dorestad|Roricus]] was granted a large part of Frisia as a benefice or [[fief]] from Lothair in 850.<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] p. 7; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 144, 177, 177 n. 375, 199; [[#UBBAR3|Reuter (1992)]] p. 30 § 850; [[#UBBAN2|Nelson (1991)]] p. 69 § 850; [[#UBBAP9|Pertzii; Kurze (1891)]] p. 39 § 850; [[#UBBAW7|Waitz (1883)]] p. 38 § 850; [[#UBBAP6|Pertz (1826)]] p. 445 § 850.</ref> As men who held military- and judicial authority on behalf of the Franks, Herioldus and Roricus can also be regarded as Frisian ''{{lang|la|duces}}''.<ref>[[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 144, 144 n. 168.</ref> Although it is uncertain whether Ubba was a native Frisian or a Scandinavian expatriate, if he was indeed involved with a Frisian benefice his forces would have probably been partly composed of Frisians.<ref>[[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] p. 137.</ref> If his troops were drawn from the Scandinavian settlement started by Herioldus over two decades before, many of Ubba's men might well have been born in Frisia.<ref name="UBBAW5-72">[[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 72.</ref> In fact, the length of Scandinavian occupation suggests that some of the Vikings from Frisia would have been native Franks and Frisians.<ref>[[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] p. 137; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 144.</ref> The considerable time that members of the Great Army appear to have spent in Ireland and the Continent suggests that these men were well accustomed to [[Germanic Christianity|Christian society]],<ref>[[#UBBAM7|McLeod, S (2013)]] pp. 83–84; [[#UBBAW5|Woolf (2007)]] p. 72.</ref> which in turn may partly explain their successes in Anglo-Saxon England.<ref name="UBBAW5-72"/> |

|||

Through the fall of the Mercian kingdom, the Great Army secured a land-route between East Anglia and Northumbria,<ref name="Downham 2007 p. 69"/> and only Wessex lay in the way of total Danish domination of Anglo-Saxon England.<ref>[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] pp. 74–75.</ref> At this point the ''Historia Regum'' reports that the Great Army split in two, with Halfdan taking his troops northwards deep into Northumbria.<ref>[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 75; [[#A3|Arnold 1885]] p. 110 (§ 875).</ref> According to the ''Chronicle'', in the winter of 874–75, Halfdan based himself on the [[River Tyne]], and waged war against the [[Picts]] and [[Strathclyde Britons]].<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 70; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 50 (§ 875); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 60 (§ 875); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 72–75 (§ 875); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] pp. 31 & 199 (§ 875); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 142 (§ 875); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 53 (§ 875); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 62 (§ 875); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 72–75 (§ 875); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 142–145 (§ 875); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 63 (§ 875); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] pp. 45–46 (§ 875); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] pp. 102–103 (§ 875).</ref> This source appears to be partly corroborated by the [[Goidelic languages|Gaelic]] ''[[Annals of Ulster]]'', an [[Irish annals|Irish source]], which refers to a bloody encounter between the Picts and ''[[Dubgaill and Finngaill|Dubgaill]]'' in 875.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 70; [[#A4|''Annala Uladh...'' 2012]] § U875.3; [[#A5|''Annala Uladh...'' 2008]] § U875.3; [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 31.</ref>{{refn|The Gaelic words ''Finngaill'' and ''Dubgaill'' translate as "Fair Foreigners" and "Dark Foreigners". Although these terms were used to differentiate different groups of Vikings in Gaelic sources, it is uncertain whether the words referred to specific ethnicities or different factions.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] pp. xvi–xvii.</ref>|group=note}} But, if the Ímar of Irish sources is identical with the Ivar of English sources, Halfdan had also conducted military actions in the north in conjunction with Ivar's previous northern campaigning.<ref name="Downham 2007 p. 70">[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 70.</ref> In 876 the ''Chronicle'' indicates that Halfdan's army had dispersed, and that he allotted his men Northumbrian lands upon which they settled.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 70; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 75; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 50 (§ 876); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] pp. 60–61 (§ 876); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 74–75 (§ 876); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 199 (§ 876); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] pp. 142–143 (§ 876); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 53 (§ 876); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 62 (§ 876); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 74–75 (§ 876); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 144–145 (§ 876); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] pp. 63–64 (§ 876); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 46 (§ 876); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 103 (§ 876).</ref> |

|||

==Viking invasion of Anglo-Saxon England== |

|||

==Further campaigning under Guthrum== |

|||

[[File:Lanhill long barrow - geograph.org.uk - 1196143.jpg|thumb|A prehistoric [[Tumulus|barrow]] at Lanhill, near [[Chippenham]] and [[Avebury]], that was associated with Ubba by the seventeenth-century antiquarian [[John Aubrey]] (d. 1697).{{refn|Aubrey, in his seventeenth-century ''[[John Aubrey#Monumenta Britannica|Monumenta Britannica]]'', called the site "Hubbaslow", and stated that it was the site "where they say that one Hubba lies buried". Aubrey appears to have assumed that Ubba was slain at the battle of Chippenham. Aubrey himself seems to have been the earliest source to associate Ubba with the site.<ref>[[#B4|Burl 2002]] p. 107; [[#H7|Hoare 1975]] Pt. 1, pp. 99–100; [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] pp. 264 n. 2 & 265; [[#J1|Jackson 1862]] p. 74 n. 1; [[#T1|Thurnam 1857]] pp. 67 & 71.</ref> It is sometimes claimed that the village of [[Hubberston]] in [[Pembrokeshire]] is named after Ubba, and that he overwintered in nearby [[Milford Haven]]. There is no evidence for this assertion,<ref name="hubberston">[[#H10|Hrdina 2011]] p. 108; [[#C8|Charles 1934]] pp. 8–9.</ref> and the name itself does not have Scandinavian roots.<ref>[[#H10|Hrdina 2011]] p. 108; [[#M7|Mills 2003]]; [[#L3|Loyn 1976]] p. 9; [[#C8|Charles 1934]] pp. 8–9.</ref> It was first recorded in the thirteenth century as ''Hobertiston'' and ''Villa Huberti'', meaning "[[Hubert]]'s Farm" and "Hubert's [[manor]]" respectively,<ref>[[#H10|Hrdina 2011]] p. 108; [[#M7|Mills 2003]].</ref> and has only been known as ''Huberston'' since the late fifteenth century.<ref name="hubberston"/>|group=note}} ]] |

|||

While Halfdan consolidated control of Northumbria, the rest of the army under kings Guthrum, Oscetel, and Anwend<ref name="splitarmy">[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 70; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 75; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 50 (§ 875); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 60 (§ 875); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 72–75 (§ 875); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 199 (§ 875); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 142 (§ 875); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 53 (§ 875); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 62 (§ 875); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 72–75 (§ 875); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 142–145 (§ 875); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 63 (§ 875); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] pp. 45–46 (§ 875); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] pp. 102–103 (§ 875).</ref> – men who may have linked up with the Great Army in 871<ref name="Downham 2007 p. 70"/> – headed southwards into East Anglia. In 875, the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' records that this army based itself at [[Cambridge]], from where operations were directed against [[Wessex]],<ref name="splitarmy"/> and the following year it is stated to have seized [[Wareham, Dorset|Wareham]].<ref name="asc-876">[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 75; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 50 (§ 876); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] pp. 60–61 (§ 876); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 74–75 (§ 876); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 199 (§ 876); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] pp. 142–143 (§ 876); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 53 (§ 876); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] p. 62 (§ 876); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 74–75 (§ 876); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 144–145 (§ 876); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] pp. 63–64 (§ 876); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 46 (§ 876); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 103 (§ 876).</ref>{{refn|Oscetel and Anwend are last recorded in 875. It is unknown if they were killed or if they left Guthrum's army.<ref>[[#A6|Abels 2013]] p. 151.</ref>|group=note}} Alfred made another truce with the Vikings in 876, but they broke it by stealth in 877 and took [[Exeter]].<ref name="asc-876"/> An approaching Viking fleet, with which Guthrum had apparently planned to link up, was destroyed by a storm, and the ''Chronicle'' reports that he was forced to withdraw to Mercia.<ref>[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] pp. 75–76; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 50 (§ 877); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 61 (§ 877); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 74–75 (§ 877); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 195 (§ 877); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 143 (§ 877); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] pp. 53–54 (§ 877); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp. 62–63 (§ 877); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 74–75 (§ 877); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 144–147 (§ 877); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 64 (§ 877); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 46 (§ 877); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 104 (§ 877).</ref>{{refn|Æthelweard alluded to a separate Viking force when noting Guthrum's actions at Cambridge and Wareham in the previous year.<ref>[[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 199 n. 4; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 160 (§ 5); [[#G2|Giles 1906]] p. 80 (§ 876); [[#S11|Stevenson 1854]] p. 431.</ref>|group=note}} |

|||

[[File:Harley MS 2278, folio 48r excerpt.jpg|thumb|left|alt=Refer to caption|A fifteenth-century depiction of [[Ívarr inn beinlausi|Ívarr]] and Ubba ravaging the countryside as it appears on folio 48[[recto|r]] of British Library Harley 2278.<ref name="combine6">[[#UBBAP19|Pinner (2010)]] pp. 161–163 fig. 53; [[#UBBAH6|''Harley MS 2278'' (n.d.)]].</ref> The ''Lives of Saints Edmund and Fremund'' presents ninth-century events in a [[chivalric]] context.<ref>[[#UBBAF3|Frantzen (2004)]] pp. 66–70.</ref>{{#tag:ref|The ''Lives of Saints Edmund and Fremund'' may be the high point of the late-medieval cult devoted to Edmund. The work draws from ''Passio sancti Eadmundi''.<ref>[[#UBBAB8|Bale (2009)]] p. 17.</ref> The ''Lives of Saints Edmund and Fremund'' represents the first significant augmentation of Edmund's legend after ''Liber de infantia sancti Eadmundi''.<ref>[[#UBBAP13|Pinner (2015)]] p. 79.</ref>|group=note}}]] |

|||

Although the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' states that much of Guthrum's army started to settle in an east-Midland region later known as the [[Five Boroughs of the Danelaw|Five Boroughs]],<ref>[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 76; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] p. 50 (§ 877); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 61 (§ 877); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 74–75 (§ 877); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] pp. 31 & 195 (§ 877); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 143 (§ 877); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] pp. 53–54 (§ 877); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp. 62–63 (§ 877); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 74–75 (§ 877); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 144–147 (§ 877); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 64 (§ 877); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] p. 46 (§ 877); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] p. 104 (§ 877).</ref><ref name="Forte p. 76">[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 76.</ref>{{refn|This Scandinavian settlement consisted of [[Derby]], [[Leicester]], [[Lincoln, England|Lincoln]], [[Nottingham]], and [[Stamford, Lincolnshire|Stamford]]. The region is first named in the tenth century.<ref>[[#H8|Higham 2013]] pp. 191–192; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 76.</ref>|group=note}} the ''Chronicle'' and Asser indicate that Guthrum launched a surprise attack against the West Saxons in the winter of 877–78.<ref>[[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 76; [[#K3|Kirby 2002]] p. 175; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] pp. 50–51 (§ 878); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] p. 61 (§ 878); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 74–77 (§ 878) & 74–75 n. 9; [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] pp. 195–196 (§ 878); [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] pp. 109 (§ 52) & 143 (§ 878); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 54 (§ 878); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp. 63–64 (§ 878); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 74–77 (§ 878); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 146–149 (§ 878); [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] p. 64 (§ 878); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] pp. 46–47 (§ 878); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] pp. 104–106 (§ 878); [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] pp. 38–40.</ref> Setting off from their base in [[Gloucester]], the Vikings drove deep into Wessex, where they sacked the [[royal vill]] of [[Chippenham]].<ref>[[#B6|Baker; Brookes 2013]] pp. 217 & 240; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 59 (§ 52); [[#C5|Cook 1906]] pp. 26–27 (§ 52); [[#G2|Giles 1906]] pp. 59–60; [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] p. 40 (§ 52); [[#S11|Stevenson 1854]] pp. 457–460 (§ 878).</ref>{{refn|A vill was an administration unit, roughly equating to a modern [[Parish (administrative division)|parish]].<ref>[[#C2|Corèdon; Williams 2004]] p. 290.</ref> Chippenham appears to have been a significant settlement during the period, and might well have been a seat of the West Saxon kings.<ref>[[#B6|Baker; Brookes 2013]] p. 240.</ref>|group=note}} It is possible that this operation was coordinated with another Viking attack in Devon that culminated in a [[Battle of Cynuit|battle at ''Arx Cynuit'']] in 878.<ref name="ReferenceA">[[#A6|Abels 2013]] p. 154; [[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 204; [[#F2|Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005]] p. 76; [[#K3|Kirby 2002]] p. 175.</ref> |

|||

In the autumn of 865, the ''Anglo Saxon Chronicle'' records that the Great Army invaded the [[Kingdom of East Anglia]], where they afterwards made peace with the East Anglians and overwintered.<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] p. 17; [[#UBBAS15|Somerville; McDonald (2014)]] p. 231 § 866; [[#UBBAG17|Gigov (2011)]] p. 19; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 11, 119; [[#UBBAP19|Pinner (2010)]] p. 28; [[#UBBAR14|Ridyard (2008)]] p. 65; [[#UBBAF5|Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005)]] p. 69; [[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. introduction ¶ 11; [[#UBBAP5|Pestell (2004)]] pp. 65–66; [[#UBBAI1|Irvine (2004)]] p. 48 § 866; [[#UBBAK1|Kirby (2002)]] p. 173; [[#UBBAO1|O'Keeffe (2001)]] p. 58 § 867; [[#UBBAS6|Swanton, M (1998)]] pp. 68–69 § 866; [[#UBBAW4|Whitelock (1996)]] pp. 30, 196 § 866; [[#UBBAT6|Taylor (1983)]] p. 34 § 867; [[#UBBAB27|Beaven (1918)]] p. 338; [[#UBBAC4|Conybeare (1914)]] p. 140 § 866; [[#UBBAG7|Giles (1914)]] p. 49 § 866; [[#UBBAG6|Gomme (1909)]] p. 58 § 866; [[#UBBAH4|Hervey (1907)]] pp. 2–3 § 866; [[#UBBAG8|Giles (1903)]] p. 351 § 866; [[#UBBAP4|Plummer; Earle (1892)]] pp. 68–69 § 866; [[#UBBAT4|Thorpe (1861a)]] pp. 130–131 § 866/867; [[#UBBAT5|Thorpe (1861b)]] p. 59 § 866; [[#UBBAS10|Stevenson, J (1853)]] p. 43 § 866.</ref> The terminology employed by this source suggests the Vikings attacked by sea.<ref>[[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 119.</ref> The invaders evidently gained valuable intelligence during the stay,<ref>[[#UBBAD3|Downham (2007)]] p. 65; [[#UBBAF5|Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005)]] pp. 69–70.</ref> as the Great Army is next stated to have left on horses gained from the subordinated population, striking deep into the [[Kingdom of Northumbria]], a fractured realm in the midst of a bitter civil war between two competing kings: [[Ælla of Northumbria|Ælla]] (died 867) and [[Osberht of Northumbria|Osberht]] (died 867).<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] p. 17; [[#UBBAS15|Somerville; McDonald (2014)]] p. 231 § 867; [[#UBBAG17|Gigov (2011)]] p. 19; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 11, 191; [[#UBBAG12|Gazzoli (2010)]] p. 37; [[#UBBAF5|Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005)]] pp. 69–70; [[#UBBAI1|Irvine (2004)]] p. 48 § 867; [[#UBBAK1|Kirby (2002)]] p. 173; [[#UBBAO1|O'Keeffe (2001)]] p. 58 § 868; [[#UBBAK2|Keynes (2001)]] p. 54; [[#UBBAS6|Swanton, M (1998)]] pp. 68–69 § 867; [[#UBBAW4|Whitelock (1996)]] pp. 30, 196 § 867; [[#UBBAT6|Taylor (1983)]] p. 34 § 868; [[#UBBAB27|Beaven (1918)]] p. 338; [[#UBBAC4|Conybeare (1914)]] p. 140 § 867; [[#UBBAG7|Giles (1914)]] p. 49 § 867; [[#UBBAG6|Gomme (1909)]] p. 58 § 867; [[#UBBAH4|Hervey (1907)]] pp. 2–3 § 867; [[#UBBAG8|Giles (1903)]] p. 351 § 867; [[#UBBAP4|Plummer; Earle (1892)]] pp. 68–69 § 867; [[#UBBAT4|Thorpe (1861a)]] pp. 130–133 § 867/868; [[#UBBAT5|Thorpe (1861b)]] p. 59 § 867; [[#UBBAS10|Stevenson, J (1853)]] p. 43 § 867.</ref> |

|||

==''Arx Cynuit'' and the brother of Ivar and Halfdan== |

|||

Most versions of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' locate the battle to [[Devon]],<ref>[[#I1|Irvine 2004]] pp. 50–51 (§ 878); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 74–77 (§ 878); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] pp. 195–196 & n. 15 (§ 878); [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 54 (§ 878); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp.63–64 (§ 878); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 74–77 (§ 878); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 146–149; [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] pp. 64–65 (§ 878); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] pp. 46–47 (§ 878); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] pp. 104–106 (§ 878).</ref>{{refn|The B- and C-versions of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' do not locate the conflict to any specific place.<ref>[[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] pp. 61–62 (§ 879); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 195 n. 15; [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 146–149.</ref>|group=note}} and Asser specified that it was fought at a fortress called ''Arx Cynuit'',<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 71; [[#H6|Haslam 2005]] p. 138; [[#M7|Mills 2003]]; [[#K3|Kirby 2002]] p. 175; [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 195 n. 16; [[#P6|Earle; Plummer 1965]] p. 93; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] pp. 110–111 (§ 58); [[#C5|Cook 1906]] pp. 27–28 (§ 54); [[#G2|Giles 1906]] pp. 61–62; [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] pp. 43–44 (§ 54); [[#S11|Stevenson 1854]] pp. 458–459.</ref> a name which appears to equate to what is today [[Countisbury]], in [[North Devon]].<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 71; [[#H6|Haslam 2005]] p. 138; [[#K3|Kirby 2002]] p. 175; [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] p. 76 n. 1; [[#L2|Lukman 1958]] p. 140.</ref>{{refn|Other locations have been suggested, including one near [[Appledore, Mid Devon|Appledore]], where it was claimed that a mound called ''Ubbaston'' or ''Whibblestan'' existed before being lost to the tide.<ref>[[#P6|Earle; Plummer 1965]] p. 93; [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] pp. 262–265.</ref>|group=note}} Asser's account also states that this Viking force made landfall in Devon from a base in [[Dyfed]], where it had previously overwintered.<ref>[[#K3|Kirby 2002]] p. 175; [[#P6|Earle; Plummer 1965]] p. 93; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] pp. 110–111 (§ 58); [[#C5|Cook 1906]] pp. 27–28 (§ 54); [[#G2|Giles 1906]] pp. 61–62; [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] pp. 43–44 (§ 54); [[#S11|Stevenson 1854]] pp. 458–459.</ref> It probably originated in Ireland.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] pp. 71 & 204.</ref> |

|||

Late in 866 the Vikings seized [[History of York|York]]<ref name="combine1">[[#UBBAG20|Gore (2016)]] p. 61; [[#UBBAM15|McGuigan (2015)]] pp. 21–22 n. 10; [[#UBBAS15|Somerville; McDonald (2014)]] p. 231 § 867; [[#UBBAG17|Gigov (2011)]] pp. 19, 43 n. 73; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 11, 126, 185; [[#UBBAD3|Downham (2007)]] p. 65; [[#UBBAF5|Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005)]] pp. 69–70; [[#UBBAI1|Irvine (2004)]] p. 48 § 867; [[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. introduction ¶ 11; [[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]] p. 52; [[#UBBAK2|Keynes (2001)]] p. 54; [[#UBBAO1|O'Keeffe (2001)]] p. 58 § 868; [[#UBBAS6|Swanton, M (1998)]] pp. 68–69 § 867; [[#UBBAW4|Whitelock (1996)]] p. 196 § 867; [[#UBBAT6|Taylor (1983)]] p. 34 § 868; [[#UBBAB27|Beaven (1918)]] p. 338; [[#UBBAC4|Conybeare (1914)]] p. 140 § 867; [[#UBBAG7|Giles (1914)]] p. 49 § 867; [[#UBBAG6|Gomme (1909)]] p. 58 § 867; [[#UBBAG8|Giles (1903)]] p. 351 § 867; [[#UBBAP4|Plummer; Earle (1892)]] pp. 68–69 § 867; [[#UBBAT4|Thorpe (1861a)]] pp. 130–133 § 867/868; [[#UBBAT5|Thorpe (1861b)]] p. 59 § 867; [[#UBBAS10|Stevenson, J (1853)]] p. 43 § 867.</ref>—one of only two [[Archbishop|archiepiscopal]] [[Episcopal see|sees]] in Anglo-Saxon England, and one of the richest trading centres in Britain.<ref>[[#UBBAF5|Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005)]] p. 70.</ref> Although Ælla and Osberht responded to this attack by joining forces against the Vikings, the chronicle indicates that their assault on York was a disaster that resulted in both their deaths.<ref name="combine1"/>{{#tag:ref|The Great Army's seizure of York is dated to 1 November ([[All Saints' Day]]) by the twelfth-century ''[[Libellus de exordio]]'',<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] pp. 17–18; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] pp. 185 n. 23, 192; [[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. asser's life of king alfred § 27 n. 54; [[#UBBAK1|Kirby (2002)]] p. 173; [[#UBBAW4|Whitelock (1996)]] p. 196 n. 7; [[#UBBAA3|Arnold (1882)]] pp. 54–55 bk. 2 ch. 6; [[#UBBAS11|Stevenson, J (1855)]] p. 654 ch. 21.</ref> and the thirteenth-century [[Flores historiarum (Wendover)|Wendover]] version of ''Flores historiarum''.<ref>[[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. asser's life of king alfred § 27 n. 54; [[#UBBAG1|Giles (1849)]] pp. 189–190; [[#UBBAC1|Coxe (1841)]] pp. 298–299.</ref> Preying upon a populated site on a [[feast day]] was a noted tactic of the Vikings. Such celebrations offered attackers easy access to potential captives who could be ransomed or sold into [[slavery]].<ref>[[#UBBAN1|Nelson (2001)]] p. 38.</ref> According to ''Libellus de exordio'',<ref>[[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. asser's life of king alfred § 27 n. 54; [[#UBBAA3|Arnold (1882)]] p. 55 bk. 2 ch. 6; [[#UBBAS11|Stevenson, J (1855)]] p. 654 ch. 21.</ref> and the twelfth-century ''[[Historia regum Anglorum]]'', the Anglo-Saxons' attempt to recapture York took place on 21 March.<ref>[[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. asser's life of king alfred § 27 n. 54; [[#UBBAS12|South (2002)]] p. 85; [[#UBBAA5|Arnold (1885)]] pp. 105–106 ch. 91; [[#UBBAS11|Stevenson, J (1855)]] p. 489.</ref> The Wendover version of ''Flores historiarum'',<ref>[[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. asser's life of king alfred § 27 n. 54; [[#UBBAG1|Giles (1849)]] pp. 189–190; [[#UBBAC1|Coxe (1841)]] pp. 298–299.</ref> and ''Historia de sancto Cuthberto'', date this attack to 23 March ([[Palm Sunday]]).<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] pp. 18–19; [[#UBBAK3|Keynes; Lapidge (2004)]] ch. asser's life of king alfred § 27 n. 54; [[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]] p. 59; [[#UBBAS12|South (2002)]] pp. 50–51 ch. 10, 85; [[#UBBAA3|Arnold (1882)]] pp. 201–202 ch. 10; [[#UBBAH7|Hodgson Hinde (1868)]] p. 142.</ref> ''Annales Lindisfarnenses et Dunelmenses'' states that Ubba crushed the Northumbrians "not long after Palm Sunday".<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] p. 20; [[#UBBAP7|Pertz (1866)]] p. 506 § 868.</ref>|group=note}} According to ''Annales Lindisfarnenses et Dunelmenses'',<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] p. 20; [[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] p. 137; [[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]] p. 60; [[#UBBAB7|Bremmer, RH (1981)]] p. 77; [[#UBBAM9|Mawer (1908–1909)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAP7|Pertz (1866)]] p. 506 § 868.</ref> and ''Historia de sancto Cuthberto'', the Northumbrians and their kings were crushed by Ubba himself.<ref>[[#UBBAB1|Barrow (2016)]] p. 85; [[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] pp. 18–19; [[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] p. 137; [[#UBBAM15|McGuigan (2015)]] p. 21; [[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 141; [[#UBBAC23|Crumplin (2004)]] pp. 65, 71 fig. 1; [[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]] pp. 59–60; [[#UBBAS12|South (2002)]] pp. 50–51 ch. 10; [[#UBBAM9|Mawer (1908–1909)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAA3|Arnold (1882)]] pp. 201–202 bk. 2 ch. 10; [[#UBBAH7|Hodgson Hinde (1868)]] p. 142.</ref>{{#tag:ref|At one point after its account of Ubba's stated victory over the Northumbrians, ''Historia de sancto Cuthberto'' expands upon the Vikings' successful campaigning across Anglo-Saxon England, and specifically identifies the Viking commanders as Ubba, ''{{lang|la|[[dux]]}}'' of the Frisians, and Hálfdan, ''{{lang|la|[[Rex (title)|rex]]}}'' of the Danes.<ref>[[#UBBAL10|Lewis (2016)]] pp. 19–20; [[#UBBAI4|IJssennagger (2015)]] p. 137; [[#UBBAG12|Gazzoli (2010)]] p. 36; [[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]] p. 61; [[#UBBAS12|South (2002)]] pp. 52–53 ch. 14; [[#UBBAJ4|Johnson-South (1991)]] p. 623; [[#UBBAB17|Bremmer, R (1984)]] pp. 359–360, 366 n. 12; [[#UBBAV3|van Houts (1984)]] p. 116, 116 n. 55; [[#UBBAM5|McTurk, RW (1976)]] pp. 104 n. 86, 120 n. 199; [[#UBBAC14|Cox (1971)]] p. 51 n. 19; [[#UBBAW2|Whitelock (1969)]] p. 227; [[#UBBAS22|Smith, AH (1928–1936b)]] p. 185; [[#UBBAM9|Mawer (1908–1909)]] p. 83; [[#UBBAA3|Arnold (1882)]] p. 204 bk. 2 ch. 14; [[#UBBAH7|Hodgson Hinde (1868)]] p. 144.</ref> ''Historia regum Anglorum'' identifies the commanders of the Vikings in 866 as Ívarr, Ubba, and Hálfdan.<ref>[[#UBBAK6|Kries (2003)]] p. 55; [[#UBBAA5|Arnold (1885)]] p. 104 ch. 91; [[#UBBAS11|Stevenson, J (1855)]] pp. 487–488.</ref> ''Libellus de exordio'' states that the Vikings who ravaged Northumbria were composed of Danes and Frisians.<ref>[[#UBBAB17|Bremmer, R (1984)]] p. 366 n. 12; [[#UBBAA3|Arnold (1882)]] p. 54 bk. 2 ch. 6.</ref>|group=note}} |

|||

[[File:Track up Wind Hill.jpg|thumb|left|Wind Hill, near [[Countisbury]], Devon, possibly the site of a disastrous Viking defeat at the hands of local men in 878.<ref>[[#M6|''MDE1236 - Countisbury Castle...'']]; [[#C1|''Countisbury circular walk...'']].</ref> Some medieval sources claim that Ubba led the vanquished army, and that he was among those slain.]] |

|||

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' does not identify the army's commander by name, but it describes him as a brother of Ivar and Halfdan, and states that he was slain in the encounter.<ref>[[#S8|Smith 2009]] pp. 129–130; [[#D1|Downham 2007]] pp. 68 n. 25 & 71; [[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 73; [[#I1|Irvine 2004]] pp. 50–51 (§ 878); [[#O1|O'Keeffe 2000]] pp. 61–62 (§ 879); [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] pp. 74–77 (§ 878); [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] pp. 195–196 (§ 878); [[#M1|McTurk 1976]] pp. 119–120; [[#S16|Stenton 1963]] p. 244 n. 2; [[#L2|Lukman 1958]] p. 140; [[#G4|Giles 1914]] p. 54 (§ 878); [[#G5|Gomme 1909]] pp. 63–64 (§ 878); [[#P5|Earle; Plummer 1892]] pp. 74–77 (§ 878); [[#T4|Thorpe 1861a]] pp. 146–149; [[#T5|Thorpe 1861b]] pp. 64–65 (§ 878); [[#S12|Stevenson 1853]] pp. 46–47 (§ 878); [[#I2|Ingram 1823]] pp. 104–106 (§ 878).</ref> Although Ubba was identified as the slain commander by the twelfth-century chronicler [[Geoffrey Gaimar]] in his [[Anglo-Norman language|Anglo-Norman]] ''[[Estoire des Engleis]]'',<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 68 n. 25; [[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 73 n. 11; [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] p. 75 n. 12; [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 195 n. 14; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 227; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 209 (§ 3141); [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] p. 265 n. 1; [[#H1|Hardy; Martin 1889]] p. 101 (§§ 3149 & 3158); [[#T1|Thurnam 1857]] p. 83; [[#S11|Stevenson 1854]] p. 767; [[#W6|Wright 1850]] p. 108 (§§ 3149 & 3158).</ref> it is unknown whether Gaimar followed an existing source or if this was an inference on his part.<ref>[[#W3|Woolf 2007]] pp. 72 n. 8 & 73 n. 11; [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 195 n. 14.</ref>{{refn|Gaimar based much of his ''Estoire des Engleis'' on the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle''.<ref>[[#S9|Spence 2013]] p. 9; [[#W3|Woolf 2007]] p. 72 n. 8.</ref>|group=note}} It is possible that Gaimar's identification was influenced by the earlier association of Ivar and Ubba in the legends surrounding Edmund's martyrdom.<ref>[[#D1|Downham 2007]] p. 68 n. 25; [[#W2|Whitelock 1996]] p. 195 n. 16.</ref> Gaimar further specified that Ubba was slain at "''bois de Pene''" , and that he was buried in Devon n a mound called "''Ubbelawe''", a word meaning "Ubba's [[Tumulus|Barrow]]".<ref>[[#H2|Hart 2003]] p. 160 n. 3; [[#S4|Swanton 1998]] p. 75 n. 12; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 227; [[#P6|Earle; Plummer 1965]] p. 93; [[#C6|Conybeare 1914]] p. 209 (§ 3141); [[#S3|Stevenson 1904]] p. 265 n. 1; [[#H1|Hardy; Martin 1889]] p. 101 (§§ 3148 & 3152); [[#T1|Thurnam 1857]] p. 83; [[#S11|Stevenson 1854]] p. 767; [[#W7|Wright 1850]] p. 108 (§§ 3148 & 3152).</ref>{{refn|A twelfth-century Latin passage in ''Pembroke College MS. 82'' states that Ubba was slain at ''Ubbelaw'' in [[Yorkshire]].<ref>[[#S10|Swan; Roberson 2013]]; [[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 228.</ref> This source relates that a brother of Ubba destroyed a church at Sheppey, and was miraculously killed in an act of [[divine retribution]], as he was swallowed alive by the ground at [[Frindsbury]], near [[Rochester, Kent|Rochester]].<ref name="ReferenceB">[[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 228.</ref> According to the late-fourteenth- or early-thirteenth-century ''[[Liber Monasterii de Hyda]]'', Ubba met his end the same way.<ref>[[#B3|Bowman; Ruch 2014]].</ref><ref>[[#W4|Whitelock 1969]] p. 228; [[#E1|Edwards 1866]] p. 10.</ref>|group=note}} |

|||

[[File:Roricus Frisian fiefdom.png|thumb|right|The ninth-century [[Frisia]]n fiefdom of [[Roricus of Dorestad|Roricus]] appears to have encompassed a region around [[Dorestad]], [[Walcheren]], and [[Wieringen]].<ref>[[#UBBAM11|McLeod, SH (2011)]] p. 143 map. 3.</ref>]] |

|||