Archaic humans

A number of varieties of Homo are grouped into the broad category of archaic humans in the period that precedes and is contemporary to the emergence of the earliest early modern humans (Homo sapiens) around 300 ka. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) from southern Ethiopia (c. 195 or 233 ka),[1][2] the remains from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco (about 315 ka) and Florisbad in South Africa (259 ka) are among the earliest remains of Homo sapiens.[3][1][4][5][6][7] The term typically includes Homo neanderthalensis (430 ± 25 ka),[8] Denisovans, Homo rhodesiensis (300–125 ka), Homo heidelbergensis (600–200 ka), Homo naledi, Homo ergaster, Homo antecessor, and Homo habilis.

There is no universal consensus on this terminology, and varieties of "archaic humans" are included under the binomial name of either Homo sapiens or Homo erectus by some authors.

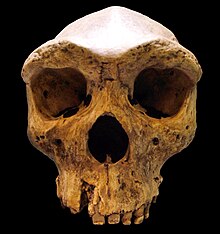

Archaic humans had a brain size averaging 1,200 to 1,400 cubic centimeters, which overlaps with the range of modern humans. Archaics are distinguished from anatomically modern humans by having a thick skull, prominent supraorbital ridges (brow ridges) and the lack of a prominent chin.[9][10]

Anatomically modern humans appear around 300,000 years ago in Africa,[11][1][4][5][6][7] and 70,000 years ago (see Toba catastrophe theory), gradually supplanting the "archaic" human varieties. Non-modern varieties of Homo are certain to have survived until after 30,000 years ago, and perhaps until as recently as 12,000 years ago. Which of these, if any, are included under the term "archaic human" is a matter of definition and varies among authors. Nonetheless, according to recent genetic studies, modern humans may have bred with "at least two groups" of archaic humans: Neanderthals and Denisovans.[12] Other studies have cast doubt on admixture being the source of the shared genetic markers between archaic and modern humans, pointing to an ancestral origin of the traits which originated 500,000–800,000 years ago.[13][14][15]

Terminology and definition

The category archaic human lacks a single, agreed definition.[9] According to one definition, Homo sapiens is a single species comprising several subspecies that include the archaics and modern humans. Under this definition, modern humans are referred to as Homo sapiens sapiens and archaics are also designated with the prefix "Homo sapiens". For example, the Neanderthals are Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, and Homo heidelbergensis is Homo sapiens heidelbergensis. Other taxonomists prefer not to consider archaics and modern humans as a single species but as several different species. In this case the standard taxonomy is used, i.e. Homo rhodesiensis, or Homo neanderthalensis.[9]

The evolutionary dividing lines that separate modern humans from archaic humans and archaic humans from Homo erectus are unclear. The earliest known fossils of anatomically modern humans such as the Omo remains from 195,000 years ago, Homo sapiens idaltu from 160,000 years ago, and Qafzeh remains from 90,000 years ago are recognizably modern humans. However, these early modern humans do possess a number of archaic traits, such as moderate, but not prominent, brow ridges.

Brain size expansion

The emergence of archaic humans is sometimes used as an example of punctuated equilibrium.[16] This occurs when a species undergoes significant biological evolution within a relatively short period. Subsequently, the species undergoes very little change for long periods until the next punctuation. The brain size of archaic humans expanded significantly from 900 cm3 (55 cu in) in erectus to 1,300 cm3 (79 cu in). Since the peak of human brain size during the archaics, it has begun to decline.[17]

Origin of language

Robin Dunbar has argued that archaic humans were the first to use language. Based on his analysis of the relationship between brain size and hominin group size, he concluded that because archaic humans had large brains, they must have lived in groups of over 120 individuals. Dunbar argues that it was not possible for hominins to live in such large groups without using language, otherwise there could be no group cohesion and the group would disintegrate. By comparison, chimpanzees live in smaller groups of up to 50 individuals.[18][19]

Fossils

- Atapuerca Mountains, Sima de los Huesos

- Saldanha man

- Altamura Man

- Kabwe skull

- Steinheim skull

- Ndutu cranium

- Dragon Man

- Cro-magnon Man

See also

References

- ^ a b c Hammond, Ashley S.; Royer, Danielle F.; Fleagle, John G. (Jul 2017). "The Omo-Kibish I pelvis". Journal of Human Evolution. 108: 199–219. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.04.004. ISSN 1095-8606. PMID 28552208.

- ^ Vidal, Celine M.; Lane, Christine S.; Asfawrossen, Asrat; et al. (Jan 2022). "Age of the oldest known Homo sapiens from eastern Africa". Nature. 601 (7894): 579–583. Bibcode:2022Natur.601..579V. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04275-8. PMC 8791829. PMID 35022610.

- ^ Stringer, C. (2016). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150237. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. PMC 4920294. PMID 27298468.

- ^ a b White, Tim D.; Asfaw, B.; DeGusta, D.; Gilbert, H.; Richards, G. D.; Suwa, G.; Howell, F. C. (2003). "Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6491): 742–47. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..742W. doi:10.1038/nature01669. PMID 12802332. S2CID 4432091.

- ^ a b Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ a b Sample, Ian (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens bones ever found shake foundations of the human story". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Ben-Ncer, Abdelouahed; Bailey, Shara E.; Freidline, Sarah E.; Neubauer, Simon; Skinner, Matthew M.; Bergmann, Inga; Le Cabec, Adeline; Benazzi, Stefano; Harvati, Katerina; Gunz, Philipp (2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..289H. doi:10.1038/nature22336. PMID 28593953.

- ^ Hublin, J. J. (2009). "The origin of Neandertals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16022–7. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616022H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904119106. JSTOR 40485013. PMC 2752594. PMID 19805257.

- ^ a b c Dawkins (2005). "Archaic homo sapiens". The Ancestor's Tale. Boston: Mariner. ISBN 978-0-618-61916-0.

- ^ Barker, Graeme (1 January 1999). Companion Encyclopedia of Archaeology. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21329-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Stringer, C. (2016). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150237. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. PMC 4920294. PMID 27298468.

- ^ Mitchell, Alanna (January 30, 2012). "DNA Turning Human Story Into a Tell-All". The New York Times. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ Telegraph Reporters (14 August 2012). "Neanderthals did not interbreed with humans, scientists find". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12.

- ^ Association, Press (4 February 2013). "Neanderthals 'unlikely to have interbred with human ancestors'". The Guardian.

- ^ Lowery, Robert K.; Uribe, Gabriel; Jimenez, Eric B.; Weiss, Mark A.; Herrera, Kristian J.; Regueiro, Maria; Herrera, Rene J. (2013). "Neanderthal and Denisova genetic affinities with contemporary humans: Introgression versus common ancestral polymorphisms". Gene. 530 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.005. PMID 23872234.

- ^ Huyssteen, Van; Huyssteen, Wentzel Van (12 April 2006). Alone in the World?. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3246-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Zyga, Lisa (15 March 2010). "Cro Magnon skull shows that our brains have shrunk". phys.org. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ CO-EVOLUTION OF NEOCORTEX SIZE, GROUP SIZE AND LANGUAGE IN HUMANS Archived June 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dunbar (1993). Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-36336-6.