Bulgarian Orthodox Church

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church with some 6.5 million members in the Republic of Bulgaria and between 1.5 and 2.0 million members in a number of European countries, the Americas and Australia. The recognition of the autocephalous Bulgarian Patriarchate by the Patriarchate of Constantinople in 927 AD makes the Bulgarian Orthodox Church the oldest autocephalous Orthodox Church in the world after the four Eastern Patriarchates: those of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem.

Canonical Status and Organisation

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church is an inseparable member of the one, holy, synodal and apostolic church and is organised as a self-governing body under the name of Patriarchate. It is divided into eleven dioceses within the boundaries of the Republic of Bulgaria and has jurisdiction over additional two dioceses for the Bulgarians in Western and Central Europe, the Americas, Canada and Australia. The dioceses of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church are divided into 58 church counties, which, in its turn, are subdivided into some 2,600 parishes.

The supreme clerical, judicial and administrative power for the whole domain of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church is exercised by the Holy Synod which includes the Patriarch and the diocesan prelates which are called by the name of metropolitans. Church life in the parishes is guided by the parish priests numbering some 1,500. The Bulgarian Orthodox Church also disposes of some 120 monasteries in Bulgaria with about 200 monks and nearly as many nuns.

Dioceses

Dioceses in Bulgaria:

- Diocese of Lovech (bulg.: Ловчанска епархия);

- Diocese of Veliko Turnovo (bulg.: Търновска епархия);

- Diocese of Stara Zagora (bulg.: Старозагорска епархия);

- Diocese of Nevrokop (bulg.: Неврокопска епархия);

Dioceses abroad:

- Diocese of Central and Western Europe (with seat in Berlin);

- Diocese of America, Canada and Australia (with seat in New York);

History of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church

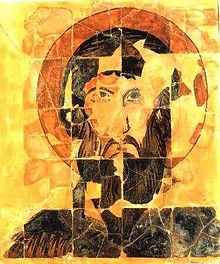

Early Christianity

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church has its origin in the flourishing Christian communities and churches, set up in the Balkans as early as the first centuries of the Christian era. Christianity was brought to the Bulgarian lands and the rest of the Balkans by Apostle Paul in the 1st century AD when the first organised Christian communities were also formed. By the beginning of the 4th century, Christianity had become the dominant religion in the region and towns like Serdica (Sofia), Philipopolis (Plovdiv) and Adrianople (Edirne) were significant centres of Christianity in the Roman Empire.

The barbaric raids and incursions in the 4th and the 5th and the settlement of Slavs and Bulgars in the 6th and the 7th century wrought considerable damage to the ecclesiastical organisation of the Christian Church in the Bulgarian lands, yet they were far from destroying it. Christianity started to pave its way from the surviving Christian communities to the surrounding Slavic mass and by the middle of the 9th century, the majority of the Bulgarian Slavs, especially those living in Thrace and Macedonia, were already Christianised. The process of conversion also enjoyed some success among the Bulgar nobility. However, it was not until the official adoption of Christianity by Tsar Boris I in 865 that conditions for the establishment of an independent Bulgarian ecclesiastical entity were created.

Establishment of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church

From the very start Boris I was aware that the cultural advancement and the re-affirmation of the sovereignty and prestige of a Christian Bulgaria could be achieved through an enlightened and zealous clergy governed by an autocephalous church. To this end, he manoeuvred between the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Roman Pope for a period of five years until the Eight Ecumenical Council granted in 870 AD the Bulgarians an autonomous Bulgarian archbishopric. The archbishopric had its seat in the Bulgarian capital of Pliska and its diocese covered the whole territory of the Bulgarian state. The pull-of-war between Rome and Constantinople was also resolved by putting the Bulgarian archbishopric under the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople from whom it obtained its first primate, its clergy and theological books.

Although the archbishopric enjoyed full internal autonomy, the goals of Boris I were scarcely fulfilled. A Greek liturgy offered by a Byzantine clergy furthered neither the cultural development of the Bulgarians, nor the consolidation of the Bulgarian state; it would have eventually resulted in the loss of both the identity of the people and the statehood of Bulgaria. Thus, the arrival of the most distinguished disciples of Saints Cyril and Methodius to Bulgaria in 886 came as a highly beneficial opportunity. Boris I entrusted the disciples with the task to instruct the future Bulgarian clergy in the Glagolitic alphabet and the Slavonic liturgy prepared by Cyril and based on the vernacular of the Bulgarian Slavs from the region of Thessaloniki. In 893, the Greek clergy was expelled from the country and the Greek language was replaced with the Slav-Bulgarian vernacular.

Autocephaly of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church

Following two decisive victories over the Byzantines at Acheloy (near the present-day city of Burgas) and Katassyrti (near Constantinople), the autonomous Bulgarian Archbishopric was proclaimed autocephalous and elevated to the rank of Patriarchate at an ecclesiastical and national council held in 919. After Bulgaria and the Byzantine Empire signed in 927 a peace treaty concluding the incessant, almost 20-year long war between them, the Patriarchate of Constantinople recognised the autocephalous status of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church and acknowledged its patriarchal dignity. Thus, the Bulgarian Patriarchate became the fifth autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church after the Patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. Its autocephalous status preceded the autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church (1346) by well over 400 years and of the Russian Orthodox Church (1596) by some 600 years. The seat of the Patriarchate was the new Bulgarian capital of Preslav although the Patriarch is likely to have resided in the town of Drastar (Silistra), an old Christian centre famous for its martyrs and Christian traditions.

The Ohrid Archbishopric

On April 5, 972, Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimisces conquered and burned down Preslav capturing Bulgarian Tsar Boris II. Patriarch Damyan managed to escape, initially to Sredetz (Sofia) in western Bulgaria. In the coming years, the residence of the Bulgarian patriarchs remained closely connected to the developments in the war between the next Bulgarian monarchist dynasty, the Comitopuli, and the Byzantine Empire. Thus, Patriarch German resided consecutively in Voden (Edessa), Maglen and Prespa (both in present-day north-western Greece). Around 990, the next patriarch, Philip, moved to Ohrid, which also became the permanent seat of the Patriarchate.

After the fall of Bulgaria under Byzantium domination in 1018, Emperor Basil II Bulgaroktonus (the “Bulgar-Slayer”) acknowledged the autocephalous status of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church and by virtue of special charters (royal decrees) set up its boundaries, dioceses, property and other privileges. The church was, however, deprived of its Patriarchal title and reduced to the rank of an archbishopric. Although the first appointed archbishop (John of Debar) was a Bulgarian, his successors, as well as the whole higher clergy, were invariably Greeks. The monks and the ordinary priests remained, however, predominantly Bulgarian, thus allowing the archbishopric to preserve to a large extent its national character, to uphold the Slavonic liturgy and to continue its contribution to the development of the Bulgarian literature. The autocephaly of the Ohrid Archbishopric remained respected during the periods of Byzantine, Bulgarian, Serbian and Ottoman rule and the church continued to exist under the name “Archbishopric of the Justiniana Prima and all Bulgaria” until its unlawful abolition in 1767.

The Turnovo Patriarchate

As a results of the successful uprising of the brothers Theodore I Peter and Ivan Asen I in 1185/1186, the foundation of the Second Bulgarian State were laid with Turnovo as its capital. Following Boris I’s principle that the sovereignty of the state is inextricably linked to the autocephaly of the Church, the two brothers immediately took steps for the restoration of the Bulgarian Patriarchate. As a start, an independent archbishopric was established in Turnovo in 1186. The struggle for the recognition of the archbishopric according to the existing canonical order and its elevation to the rank of a Patriarchate took, however, almost 50 years. Following the example of Boris I, Bulgarian Tsar Kaloyan manoeuvred for years between the Patriarch of Constantinople and Pope Innocent III until the latter finally proclaimed the Turnovo Archbishop Vassily “Primate and Archbishop of all Bulgaria and Walachia” in 1203. The union with the Roman Catholic Church continued for well over three decades.

Under the reign of Tsar Ivan Asen II (1218-1241), conditions finally were created for the termination of the union with Rome and for the recognition of the autocephalous status of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. In 1235 a church council was convened in the town of Lampsakos. Under the presidency of by Patriarch Germanius II of Constantinople and with the consent of all Eastern Patriarchs, the council confirmed the Patriarchal dignity of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church and consecrated the Bulgarian archbishop German Patriarch.

Despite the shrinking of the diocese of the Turnovo Patriarchate at the end of the 13th century, its authority in the Eastern Orthodox world remained high. It was the Patriarch of Turnovo who confirmed the patriarchal dignity of the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1346, despite protests by the Constantinople. It was also under the wing of the Patriarchate that the Turnovo Literary School developed in the 14th century with scholars of the rank of Patriarch Evtimiy, Grigorii Tsamblak, Konstantin of Kostenets. A considerable upsurge was noted in the field of literature, architecture, and painting, the religious and theological literature flourished.

After the fall of Turnovo under the Ottomans in 1393 and the sending of Patriarch Evtimiy into exile, the autocephalous church organization was destroyed once again. The Bulgarian diocese was subordinated to the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The other Bulgarian religious centre – the Ohrid Archbishopric – managed to survive a few centuries more (until 1767), as a stronghold of faith and piety.

Ottoman rule

The period of the Ottoman rule was the hardest in the history of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, to the same extent to which it was also the hardest in the history of the Bulgarian people. During and immediately after the Ottoman conquest, the vast majority of the Bulgarian churches and monasteries, including the Patriarchal Cathedral church of the Holy Ascension in Turnovo, were razed to the ground, with most of the surviving ones being turned into mosques. Most of the clergy perished, while the intelligentsia around the Turnovo Literary School fled to neighbouring Serbia, Wallachia, Moldova or to Russia.

The Church gave a number of martyrs as many districts and almost all larger towns in the Bulgarian provinces of the Ottoman Empire were subjected to forceful conversion to Islam as early as the first years after the conquest. Stunning were the feats of St. George of Kratovo (+1515), St. Nicholas of Sofia (+1515), Bishop Vissarion of Smolen (+1670), Damaskin of Gabrovo (+1771), St. Zlata of Muglen (+1795), St. John the Bulgarian (+1814), St. Ignatius of Stara Zagora (+1814), St. Onouphry of Gabrovo (+1818) and of many others who perished defending their faith.

The virtual decapitation of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church was further emphasised by its full subordination to the Patriarch of Constantinople. The millet system in the Ottoman Empire granted a number of important civil and judicial functions to the Patriarch of Constantinople and the diocesan metropolitans. As the higher Bulgarian church clerics were replaced by Greek ones at the very beginning of the Ottoman domination, the Bulgarian population was subjected before long to double oppression – political by the Ottomans and cultural by the Greek clergy. With the rise of Greek nationalism in the second half of the 18th century, the cultural oppression turned into an open assimilatory policy which was aimed at imposing the Greek language and a Greek consciousness on the emerging Bulgarian bourgeoisie and which used as its basic tool the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The opening of a number of schools with all-round Greek language curriculum and the virtual banning of the Bulgarian liturgy at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century threatened the very survival of the Bulgarians as a separate nation with its own, distinct national culture.

If something was, however, instrumental in the preservation of the Bulgarian language and the Bulgarian national consciousness throughout the centuries of Ottoman domination, it was the Bulgarian monasteries, especially the Zograph and Hilendar Monasteries on Mount Athos, as well as the Rila, Troyan, Etropole, Dryanovo, Cherepish and Dragalevtsi Monasteries in Bulgaria. The monasteries managed to preserve their national character and continued the traditions of the Slavonic liturgy and the Bulgarian literature. They also kept monastery schools and carried out other educational activities, which, if not more, managed to keep the flame of the Bulgarian culture burning until better times came.

The Bulgarian Exarchate

In 1762, St. Paissiy of Hilendar (1722-1773), a monk from the south-western Bulgarian town of Bansko, wrote a short historical work which, apart from being the first work written in the Modern Bulgarian vernacular, was also the first ardent call for a national awakening. In History of Slav-Bulgarians, Paissiy urged his compatriots to throw off the subjugation to the Greek language and culture. The example of Paissiy was followed by a number of other awakeners, including St. Sophroniy of Vratsa (Sofroni Vrachanski) (1739-1813), hieromonk Spiridon of Gabrovo, hieromonk Yoakim Kurchovski (+1820), hieromonk Kiril Peichinovich (+1845).

The result of the work of Paissiy and his followers began before long to give fruit. Discontent with the supremacy of the Greek clergy started to flare up in several Bulgarian dioceses as early as the 1820s. It was not, however, until the 1850 that the Bulgarians initiated a purposeful struggle against the Greek clerics in a number of bishoprics demanding their replacement with Bulgarian ones. By that time, most Bulgarian religious leaders had realised that any further struggle for the rights of the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire could not succeed unless they managed to obtain at least some degree of autonomy from the Patriarchate of Constantinople. As the Ottomans identified nationality with religion and the Bulgarians were Eastern Orthodox, they were automatically added to the “Roum-Milet”, i.e., the Greeks. Thus, if the Bulgarians wanted to have Bulgarian schools and liturgy in Bulgarian, they needed an independent ecclesiastical organisation.

The struggle between the Bulgarians, led by Neofit Bozveli and Ilarion Makariopolski, and the Greeks intensified throughout the 1860s. As the Greek clerics were ousted from most Bulgarian bishoprics at the end of the decade, the whole of northern Bulgaria, as well as the northern parts of Thrace and Macedonia had, by all intents and purposes, seceded from the Patriarchate. In recognition of that, the Ottoman government restored the once unlawfully destroyed Bulgarian Patriarchate under the name of "Bulgarian Exarchate" by a decree (firman) of the Sultan promulgated on February 28th, 1870. The original Exarchate extended over present-day northern Bulgaria (Moesia), Thrace without the Vilayet of Adrianople, as well as over north-eastern Macedonia. After the Christian population of the bishoprics of Skopje and Ohrid voted in 1874 overwhelmingly in favour of joining the Exarchate (Skopje by 91%, Ohrid by 97%), the Bulgarian Exarchate became in control of the whole of Vardar and Pirin Macedonia. The Exarchate was also represented in the whole of southern Macedonia and the Vilayet of Adrianople by vicars. Thus, the borders of the Exarchate included all Bulgarian districts in the Ottoman Empire.

The decision on the secession of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church was far from well accepted by the Patriarchate of Constantinople which promptly declared the Bulgarian Exarchate schismatic and declared its adherents heretics. Although there was nothing non-canonical about the status and the guiding principles of the Exarchate, the Patriarchate argued that “surrender of Orthodoxy to ethnic nationalism” was essentially a manifestation of heresy.

The first Bulgarian Exarch was Antim I who was elected by the Holy Synod of the Exarchate in February, 1872. He was discharged by the Ottoman government immediately after the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War, 1877-78 on April 24, 1877, and was sent into exile in Ankara. Under the guidance of his successor, Joseph I, the Exarchate managed to develop and considerably extend its church and school network in the Bulgarian Principality, Eastern Rumelia, Macedonia and the Adrianople Vilayet. On the eve of the Balkan Wars, in Macedonia and the Adrianople Vilayet alone, the Bulgarian Exarchate disposed of seven dioceses with prelates and eight more with acting chairmen in charge and 38 vicariates, 1,218 parishes and 1,212 parish priests, 64 monasteries and 202 chapels, as well as of 1 373 schools with 2,266 teachers and 78,854 pupils.

After World War I, by virtue of the peace treaties, the Bulgarian Exarchate was deprived of its dioceses in Macedonia and Aegean Thrace. Exarch Joseph I transferred his offices from Istanbul to Sofia as early as 1913. After the death of Joseph I in 1915, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church was not in a position to elect its regular head for a total of three decades.

Second restoration of the Bulgarian Patriarchate

Conditions for the restoration of the Bulgarian Patriarchate and the election of head of the Bulgarian Church were created after World War II. In 1945 the schism was lifted and the Patriarch of Constantinople recognised the autocephaly of the Bulgarian Church. In 1950, the Holy Synod adopted a new Statute which paved the way for the restoration of the Patriarchate and in 1953, it elected the Metropolitan of Plovdiv, Cyril, Bulgarian Patriarch. After the death of Patriarch Cyril in 1971, the Church elected in his place the Metropolitan of Lovech, Maxim, who is the current Bulgarian Patriarch.

External links

- The official website of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church

- History of Bulgaria and the Bulgarian Orthodox Church according to the Catholic Encyclopaedia

- A short history of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church by CNEWA, the papal agency for humanitarian and pastoral support

- The Bulgarian Orthodox Church according to Overview of World Religions